Roald Dahl lost a child to measles. Here's what he has to say about the new outbreaks.

Olivia Dahl, shortly before her death from measles in 1962.

In 1962, the world was a remarkably different place: Neil Armstrong had yet to take his first steps on the lunar surface, John F. Kennedy was serving as president of the United States, and the Beatles were still a few years away from superstardom, having just recorded their first single.

The word “measles” was also a household name. Measles, which still exists in parts of the world today, is a highly contagious viral infection that typically causes fever, cough, muscle pain, fatigue, and a distinctive red rash. Measles was so pervasive around the world in 1962 that most children had gotten sick with it before the age of fifteen—but even though it was common, it was far from harmless. Measles killed around 400 to 500 people per year in the United States, and approximately 2.6 million people each year worldwide. Countless others suffered severe complications from measles, such as permanent blindness.

Tragedy hits home

Author Roald Dahl at his Buckinghamshire home with Olivia, daughter Chantal, and wife Patricia Neal in 1960.

Ben Martin / Getty Images

That year, British author Roald Dahl was beginning to make a name for himself, having just published his best-selling book James and the Giant Peach. Dahl, who would go on to write some of the most well-loved children’s books of the century, lived in southern England with his wife and three children. One day, Dahl and his wife, actress Patricia Neal, received word that there was an outbreak of measles at his daughters’ school.

While some parents quarantined their children, many others also considered measles a harmless childhood disease. Neal later recalled in her autobiography that a family member had advised her to “let the girls get measles,” thinking it would strengthen their immune systems and be “good for them.” Reluctantly, Dahl and Neal let their two school-aged children, Olivia and Chantal, continue school. Olivia, then aged seven, fell sick with the measles not long after that.

Neither Dahl nor Neal were terribly concerned about Olivia’s infection. Dahl would write later that it seemed to be taking its “usual course,” and the two would read and spend time together while Olivia rested. After a few days of fever and fatigue, Dahl wrote, Olivia seemed like she was “well on the road to recovery.”

But one afternoon, as the two sat on Olivia’s bed making animals out of pipe cleaners, Dahl noticed that Olivia’s “fingers and her mind were not working together.” When Dahl asked how she was feeling, Olivia replied, “I feel all sleepy.”

Within an hour, Dahl wrote, Olivia was unconscious. Within 12 hours, she was dead.

Olivia died of measles encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain caused by an infection. Approximately 1 in 1,000 people infected with measles develop encephalitis, and of those who develop it, between 10 and 20 percent will die.

Dahl was overcome with grief and wracked with guilt for being unable to prevent his daughter’s death. Mourning, Dahl threw himself into his writing and, in his spare time, spent hours lovingly constructing a rock garden on Olivia’s grave in a local churchyard.

After Olivia’s death, Dahl wrote sixteen novels and several collections of short stories, including Matilda, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, which garnered him worldwide acclaim. His most influential piece of writing, however, wasn’t written until 1986.

A father's plea

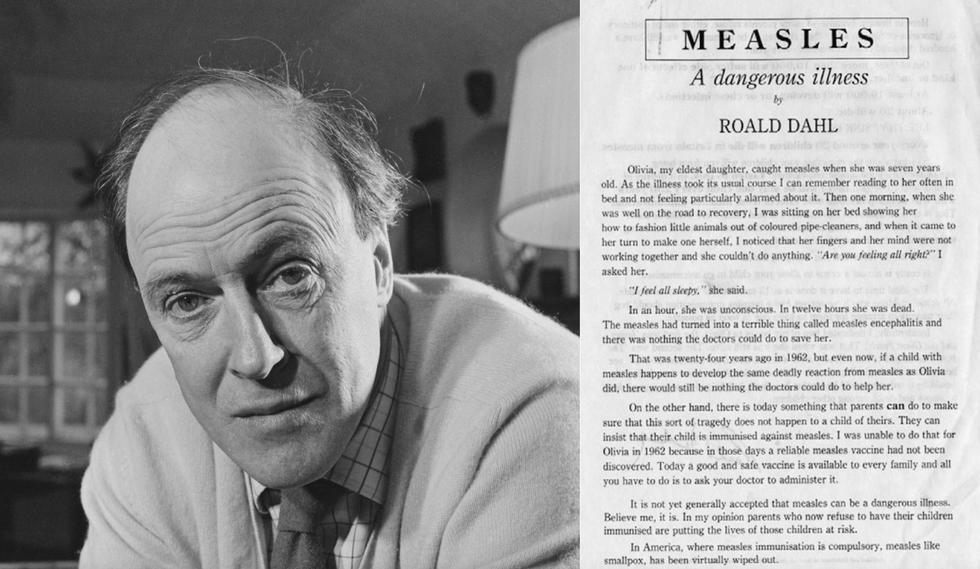

Roald Dahl and the open letter he wrote in 1986, encouraging parents to vaccinate their children against measles.

By 1986, measles was no longer the global health threat that it had been in the 1960s, thanks to a measles vaccine that became available just one year after Olivia had died. Still, in the United Kingdom alone, approximately 80,000 people every year were infected with measles. This bothered Dahl, especially since measles rates in the United States had dropped by 98 percent compared to pre-vaccine years. “Why do we have so much measles in Britain when the Americans have virtually gotten rid of it?,” Dahl was reported to have said.

So Dahl set out to prevent a tragedy like Olivia’s from happening again. With encouragement from several prominent public health activists, Dahl wrote an open letter addressed to parents in the UK. The letter recounted his daughter’s death from encephalitis and begged parents to protect their own children from measles:

“...there is today something that parents can do to make sure that this sort of tragedy does not happen to a child of theirs. They can insist that their child is immunised [sic] against measles. I was unable to do that for Olivia in 1962 because in those days a reliable measles vaccine had not been discovered. Today a good and safe vaccine is available to every family and all you have to do is to ask your doctor to administer it.”

Dahl went on to say that although many parents still viewed measles as a harmless illness, he knew from experience that it was not. Measles was capable of causing disability and death, Dahl wrote, whereas a child had a better chance of “choking on a chocolate bar” than developing any serious complication from the vaccine. Dahl ended his letter by saying how happy he knew Olivia would be “if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.”

Dahl’s letter was published in early 1986 and distributed to local healthcare workers, schools, and to parents of children who were particularly at risk. As the letter circulated, vaccination rates continued to climb year after year.

Thirty-one years after Dahl’s letter was published, and 55 years after Olivia’s death, the World Health Organization declared in 2017 that measles had officially been eradicated for the first time in the UK thanks to high rates of vaccination.

A small step back

As vaccination rates decline, measles is now making a strong comeback in the United States and elsewhere.

Getty Images

Today, vaccination rates for the measles are in decline, and countries like the UK and the US, who had once eradicated measles completely, are now seeing a comeback. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that between December 1, 2023 and January 23, 2024, 23 cases of measles had been confirmed across multiple states. The majority of these cases, they reported, were among children and adolescents who had traveled internationally and had not yet been vaccinated even though they were eligible to do so.

Roald Dahl passed away in 1990, but fortunately, his writing continues to live on. While readers can explore fantastical worlds through his novels and short stories, they can also look back to a reality when tragic deaths like Olivia’s happened far too often. The difference is that today, thanks to modern science, we now have the tools to stop them.

This man spent over 70 years in an iron lung. What he was able to accomplish is amazing.

Paul Alexander spent more than 70 years confined to an iron lung after a polio infection left him paralyzed at age 6. Here, Alexander uses a mirror attached to the top of his iron lung to view his surroundings.

It’s a sight we don’t normally see these days: A man lying prone in a big, metal tube with his head sticking out of one end. But it wasn’t so long ago that this sight was unfortunately much more common.

In the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of people each year were infected by polio—a highly contagious virus that attacks nerves in the spinal cord and brainstem. Many people survived polio, but a small percentage of people who did were left permanently paralyzed from the virus, requiring support to help them breathe. This support, known as an “iron lung,” manually pulled oxygen in and out of a person’s lungs by changing the pressure inside the machine.

Paul Alexander was one of several thousand who were infected and paralyzed by polio in 1952. That year, a polio epidemic swept the United States, forcing businesses to close and polio wards in hospitals all over the country to fill up with sick children. When Paul caught polio in the summer of 1952, doctors urged his parents to let him rest and recover at home, since the hospital in his home suburb of Dallas, Texas was already overrun with polio patients.

Paul rested in bed for a few days with aching limbs and a fever. But his condition quickly got worse. Within a week, Paul could no longer speak or swallow, and his parents rushed him to the local hospital where the doctors performed an emergency procedure to help him breathe. Paul woke from the surgery three days later, and found himself unable to move and lying inside an iron lung in the polio ward, surrounded by rows of other paralyzed children.

But against all odds, Paul lived. And with help from a physical therapist, Paul was able to thrive—sometimes for small periods outside the iron lung.

The way Paul did this was to practice glossopharyngeal breathing (or as Paul called it, “frog breathing”), where he would trap air in his mouth and force it down his throat and into his lungs by flattening his tongue. This breathing technique, taught to him by his physical therapist, would allow Paul to leave the iron lung for increasing periods of time.

With help from his iron lung (and for small periods of time without it), Paul managed to live a full, happy, and sometimes record-breaking life. At 21, Paul became the first person in Dallas, Texas to graduate high school without attending class in person, owing his success to memorization rather than taking notes. After high school, Paul received a scholarship to Southern Methodist University and pursued his dream of becoming a trial lawyer and successfully represented clients in court.

Throughout his long life, Paul was also able to fly on a plane, visit the beach, adopt a dog, fall in love, and write a memoir using a plastic stick to tap out a draft on a keyboard. In recent years, Paul joined TikTok and became a viral sensation with more than 330,000 followers. In one of his first videos, Paul advocated for vaccination and warned against another polio epidemic.

Paul was reportedly hospitalized with COVID-19 at the end of February and died on March 11th, 2024. He currently holds the Guiness World Record for longest survival inside an iron lung—71 years.

Polio thankfully no longer circulates in the United States, or in most of the world, thanks to vaccines. But Paul continues to serve as a reminder of the importance of vaccination—and the power of the human spirit.

““I’ve got some big dreams. I’m not going to accept from anybody their limitations,” he said in a 2022 interview with CNN. “My life is incredible.”

When doctors couldn’t stop her daughter’s seizures, this mom earned a PhD and found a treatment herself.

Savannah Salazar (left) and her mother, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar, who earned a PhD in neurobiology in the quest for a treatment of her daughter's seizure disorder.

Twenty-eight years ago, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar woke to the sound of her daughter, two-year-old Savannah, in the midst of a medical emergency.

“I entered [Savannah’s room] to see her tiny little body jerking about violently in her bed,” Tracy said in an interview. “I thought she was choking.” When she and her husband frantically called 911, the paramedic told them it was likely that Savannah had had a seizure—a term neither Tracy nor her husband had ever heard before.

Over the next several years, Savannah’s seizures continued and worsened. By age five Savannah was having seizures dozens of times each day, and her parents noticed significant developmental delays. Savannah was unable to use the restroom and functioned more like a toddler than a five-year-old.

Doctors were mystified: Tracy and her husband had no family history of seizures, and there was no event—such as an injury or infection—that could have caused them. Doctors were also confused as to why Savannah’s seizures were happening so frequently despite trying different seizure medications.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Savannah with Lennox-Gaustaut Syndrome, or LGS, an epilepsy disorder with no cure and a poor prognosis. People with LGS are often resistant to several kinds of anti-seizure medications, and often suffer from developmental delays and behavioral problems. People with LGS also have a higher chance of injury as well as a higher chance of sudden unexpected death (SUDEP) due to the frequent seizures. In about 70 percent of cases, LGS has an identifiable cause such as a brain injury or genetic syndrome. In about 30 percent of cases, however, the cause is unknown.

Watching her daughter struggle through repeated seizures was devastating to Tracy and the rest of the family.

“This disease, it comes into your life. It’s uninvited. It’s unannounced and it takes over every aspect of your daily life,” said Tracy in an interview with Today.com. “Plus it’s attacking the thing that is most precious to you—your kid.”

Desperate to find some answers, Tracy began combing the medical literature for information about epilepsy and LGS. She enrolled in college courses to better understand the papers she was reading.

“Ironically, I thought I needed to go to college to take English classes to understand these papers—but soon learned it wasn’t English classes I needed, It was science,” Tracy said. When she took her first college science course, Tracy says, she “fell in love with the subject.”

Tracy was now a caregiver to Savannah, who continued to have hundreds of seizures a month, as well as a full-time student, studying late into the night and while her kids were at school, using classwork as “an outlet for the pain.”

“I couldn’t help my daughter,” Tracy said. “Studying was something I could do.”

Twelve years later, Tracy had earned a PhD in neurobiology.

After her post-doctoral training, Tracy started working at a lab that explored the genetics of epilepsy. Savannah’s doctors hadn’t found a genetic cause for her seizures, so Tracy decided to sequence her genome again to check for other abnormalities—and what she found was life-changing.

Tracy discovered that Savannah had a calcium channel mutation, meaning that too much calcium was passing through Savannah’s neural pathways, leading to seizures. The information made sense to Tracy: Anti-seizure medications often leech calcium from a person’s bones. When doctors had prescribed Savannah calcium supplements in the past to counteract these effects, her seizures had gotten worse every time she took the medication. Tracy took her discovery to Savannah’s doctor, who agreed to prescribe her a calcium blocker.

The change in Savannah was almost immediate.

Within two weeks, Savannah’s seizures had decreased by 95 percent. Once on a daily seven-drug regimen, she was soon weaned to just four, and then three. Amazingly, Tracy started to notice changes in Savannah’s personality and development, too.

“She just exploded in her personality and her talking and her walking and her potty training and oh my gosh she is just so sassy,” Tracy said in an interview.

Since starting the calcium blocker eleven years ago, Savannah has continued to make enormous strides. Though still unable to read or write, Savannah enjoys puzzles and social media. She’s “obsessed” with boys, says Tracy. And while Tracy suspects she’ll never be able to live independently, she and her daughter can now share more “normal” moments—something she never anticipated at the start of Savannah’s journey with LGS. While preparing for an event, Savannah helped Tracy get ready.

“We picked out a dress and it was the first time in our lives that we did something normal as a mother and a daughter,” she said. “It was pretty cool.”