Roald Dahl lost a child to measles. Here's what he has to say about the new outbreaks.

Olivia Dahl, shortly before her death from measles in 1962.

In 1962, the world was a remarkably different place: Neil Armstrong had yet to take his first steps on the lunar surface, John F. Kennedy was serving as president of the United States, and the Beatles were still a few years away from superstardom, having just recorded their first single.

The word “measles” was also a household name. Measles, which still exists in parts of the world today, is a highly contagious viral infection that typically causes fever, cough, muscle pain, fatigue, and a distinctive red rash. Measles was so pervasive around the world in 1962 that most children had gotten sick with it before the age of fifteen—but even though it was common, it was far from harmless. Measles killed around 400 to 500 people per year in the United States, and approximately 2.6 million people each year worldwide. Countless others suffered severe complications from measles, such as permanent blindness.

Tragedy hits home

Author Roald Dahl at his Buckinghamshire home with Olivia, daughter Chantal, and wife Patricia Neal in 1960.

Ben Martin / Getty Images

That year, British author Roald Dahl was beginning to make a name for himself, having just published his best-selling book James and the Giant Peach. Dahl, who would go on to write some of the most well-loved children’s books of the century, lived in southern England with his wife and three children. One day, Dahl and his wife, actress Patricia Neal, received word that there was an outbreak of measles at his daughters’ school.

While some parents quarantined their children, many others also considered measles a harmless childhood disease. Neal later recalled in her autobiography that a family member had advised her to “let the girls get measles,” thinking it would strengthen their immune systems and be “good for them.” Reluctantly, Dahl and Neal let their two school-aged children, Olivia and Chantal, continue school. Olivia, then aged seven, fell sick with the measles not long after that.

Neither Dahl nor Neal were terribly concerned about Olivia’s infection. Dahl would write later that it seemed to be taking its “usual course,” and the two would read and spend time together while Olivia rested. After a few days of fever and fatigue, Dahl wrote, Olivia seemed like she was “well on the road to recovery.”

But one afternoon, as the two sat on Olivia’s bed making animals out of pipe cleaners, Dahl noticed that Olivia’s “fingers and her mind were not working together.” When Dahl asked how she was feeling, Olivia replied, “I feel all sleepy.”

Within an hour, Dahl wrote, Olivia was unconscious. Within 12 hours, she was dead.

Olivia died of measles encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain caused by an infection. Approximately 1 in 1,000 people infected with measles develop encephalitis, and of those who develop it, between 10 and 20 percent will die.

Dahl was overcome with grief and wracked with guilt for being unable to prevent his daughter’s death. Mourning, Dahl threw himself into his writing and, in his spare time, spent hours lovingly constructing a rock garden on Olivia’s grave in a local churchyard.

After Olivia’s death, Dahl wrote sixteen novels and several collections of short stories, including Matilda, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, which garnered him worldwide acclaim. His most influential piece of writing, however, wasn’t written until 1986.

A father's plea

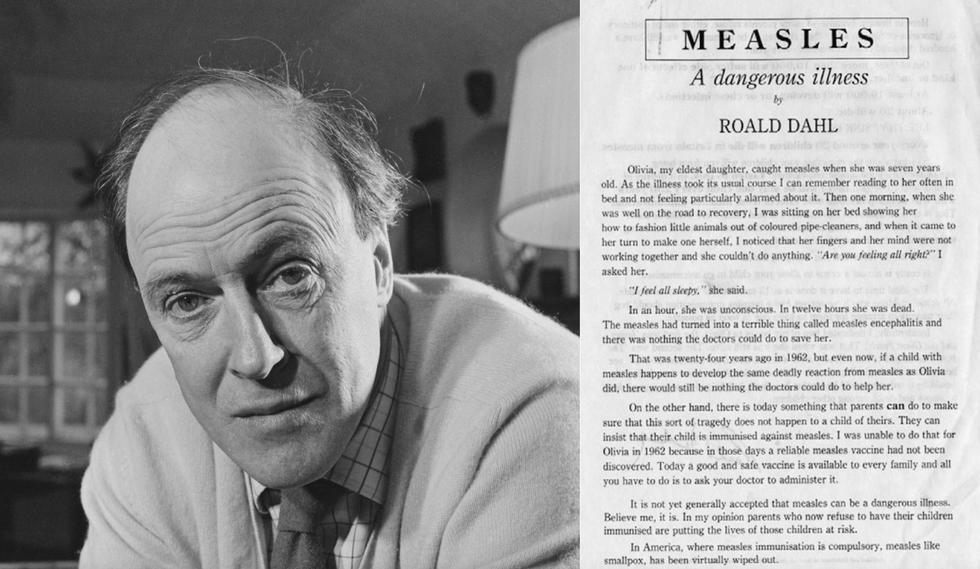

Roald Dahl and the open letter he wrote in 1986, encouraging parents to vaccinate their children against measles.

By 1986, measles was no longer the global health threat that it had been in the 1960s, thanks to a measles vaccine that became available just one year after Olivia had died. Still, in the United Kingdom alone, approximately 80,000 people every year were infected with measles. This bothered Dahl, especially since measles rates in the United States had dropped by 98 percent compared to pre-vaccine years. “Why do we have so much measles in Britain when the Americans have virtually gotten rid of it?,” Dahl was reported to have said.

So Dahl set out to prevent a tragedy like Olivia’s from happening again. With encouragement from several prominent public health activists, Dahl wrote an open letter addressed to parents in the UK. The letter recounted his daughter’s death from encephalitis and begged parents to protect their own children from measles:

“...there is today something that parents can do to make sure that this sort of tragedy does not happen to a child of theirs. They can insist that their child is immunised [sic] against measles. I was unable to do that for Olivia in 1962 because in those days a reliable measles vaccine had not been discovered. Today a good and safe vaccine is available to every family and all you have to do is to ask your doctor to administer it.”

Dahl went on to say that although many parents still viewed measles as a harmless illness, he knew from experience that it was not. Measles was capable of causing disability and death, Dahl wrote, whereas a child had a better chance of “choking on a chocolate bar” than developing any serious complication from the vaccine. Dahl ended his letter by saying how happy he knew Olivia would be “if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.”

Dahl’s letter was published in early 1986 and distributed to local healthcare workers, schools, and to parents of children who were particularly at risk. As the letter circulated, vaccination rates continued to climb year after year.

Thirty-one years after Dahl’s letter was published, and 55 years after Olivia’s death, the World Health Organization declared in 2017 that measles had officially been eradicated for the first time in the UK thanks to high rates of vaccination.

A small step back

As vaccination rates decline, measles is now making a strong comeback in the United States and elsewhere.

Getty Images

Today, vaccination rates for the measles are in decline, and countries like the UK and the US, who had once eradicated measles completely, are now seeing a comeback. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that between December 1, 2023 and January 23, 2024, 23 cases of measles had been confirmed across multiple states. The majority of these cases, they reported, were among children and adolescents who had traveled internationally and had not yet been vaccinated even though they were eligible to do so.

Roald Dahl passed away in 1990, but fortunately, his writing continues to live on. While readers can explore fantastical worlds through his novels and short stories, they can also look back to a reality when tragic deaths like Olivia’s happened far too often. The difference is that today, thanks to modern science, we now have the tools to stop them.

A robot server, controlled remotely by a disabled worker, delivers drinks to patrons at the DAWN cafe in Tokyo.

A sleek, four-foot tall white robot glides across a cafe storefront in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district, holding a two-tiered serving tray full of tea sandwiches and pastries. The cafe’s patrons smile and say thanks as they take the tray—but it’s not the robot they’re thanking. Instead, the patrons are talking to the person controlling the robot—a restaurant employee who operates the avatar from the comfort of their home.

It’s a typical scene at DAWN, short for Diverse Avatar Working Network—a cafe that launched in Tokyo six years ago as an experimental pop-up and quickly became an overnight success. Today, the cafe is a permanent fixture in Nihonbashi, staffing roughly 60 remote workers who control the robots remotely and communicate to customers via a built-in microphone.

More than just a creative idea, however, DAWN is being hailed as a life-changing opportunity. The workers who control the robots remotely (known as “pilots”) all have disabilities that limit their ability to move around freely and travel outside their homes. Worldwide, an estimated 16 percent of the global population lives with a significant disability—and according to the World Health Organization, these disabilities give rise to other problems, such as exclusion from education, unemployment, and poverty.

These are all problems that Kentaro Yoshifuji, founder and CEO of Ory Laboratory, which supplies the robot servers at DAWN, is looking to correct. Yoshifuji, who was bedridden for several years in high school due to an undisclosed health problem, launched the company to help enable people who are house-bound or bedridden to more fully participate in society, as well as end the loneliness, isolation, and feelings of worthlessness that can sometimes go hand-in-hand with being disabled.

“It’s heartbreaking to think that [people with disabilities] feel they are a burden to society, or that they fear their families suffer by caring for them,” said Yoshifuji in an interview in 2020. “We are dedicating ourselves to providing workable, technology-based solutions. That is our purpose.”

Shota, Kuwahara, a DAWN employee with muscular dystrophy, agrees. "There are many difficulties in my daily life, but I believe my life has a purpose and is not being wasted," he says. "Being useful, able to help other people, even feeling needed by others, is so motivational."

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.