Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

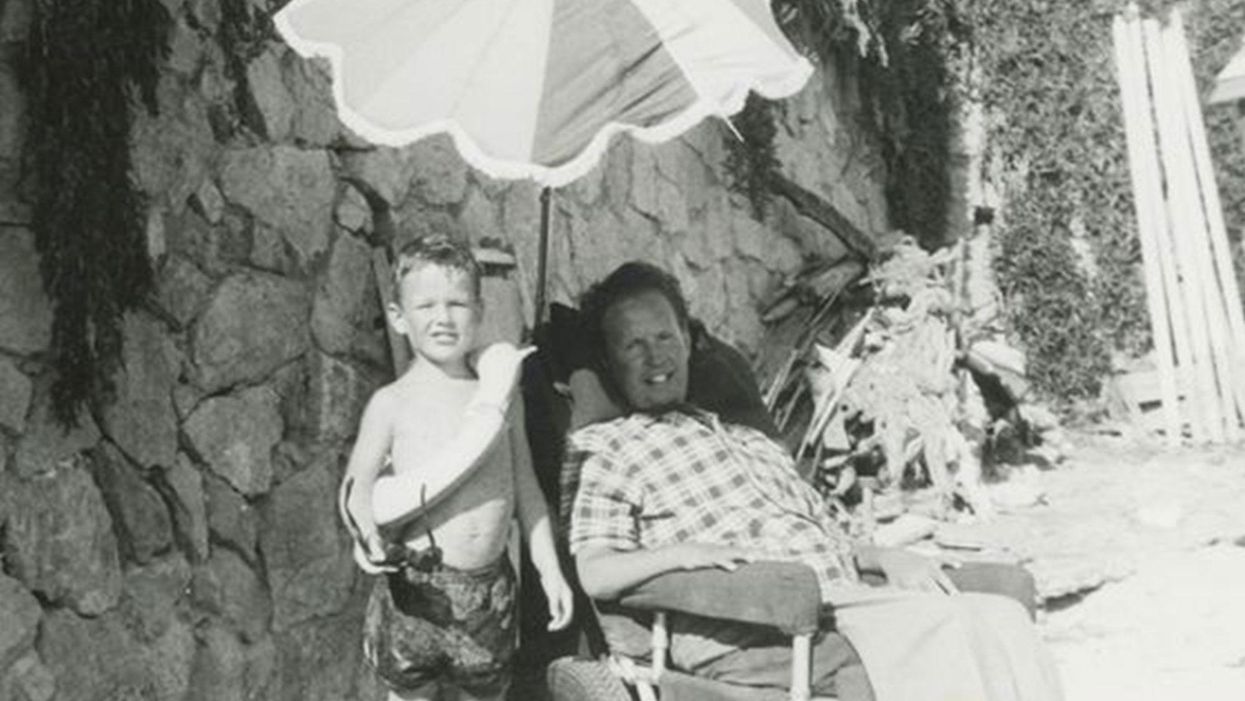

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

Enter our writing contest for a chance to win a cash prize and publication on leapsmag.

Last year, we sponsored a short story contest, asking writers to share a fictional vision of how emerging technology might shape the future. This year, the competition has a new spin.

The Prompt:

Write a personal essay of up to 2000 words describing how a new advance in medicine or science has profoundly affected your life.

The Rules:

Submissions must be received by midnight EST on September 20th, 2019. Send your original, previously unpublished essay as a double-spaced attachment in size 12 Times New Roman font to kira@leapsmag.com. Include your name and a short bio. It is free to enter, and authors retain all ownership of their work. Upon submitting an entry, the author agrees to grant leapsmag one-time nonexclusive publication rights.

All submissions will be judged by the Editor-in-Chief on the basis of insightfulness, quality of writing, and relevance to the prompt. The Contest is open to anyone around the world of any age, except for the friends and family of leapsmag staff and associates.

The winners will be announced by October 31st, 2019.

The Prizes:

Grand Prize: $500, publication of your story on leapsmag, and promotion on our social media channels.

First Runner-Up: $100 and a shout-out on our social media channels.

Good luck!

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Men and Women Experience Pain Differently. Learning Why Could Lead to Better Drugs.

According to the CDC, one fifth of American adults live with chronic pain, and women are affected more than men.

It's been more than a decade since Jeannette Rotondi has been pain-free. A licensed social worker, she lives with five chronic pain diagnoses, including migraines. After years of exploring treatment options, doctors found one that lessened the pain enough to allow her to "at least get up."

"With all that we know now about genetics and the immune system, I think the future of pain medicine is more precision-based."

Before she says, "It was completely debilitating. I was spending time in dark rooms. I got laid off from my job." Doctors advised against pregnancy; she and her husband put off starting a family for almost a decade.

"Chronic pain is very unpredictable," she says. "You cannot schedule when you'll be in debilitative pain or cannot function. You don't know when you'll be hit with a flare. It's constantly in your mind. You have to plan for every possibly scenario. You need to carry water, medications. But you can't plan for everything." Even odors can serve as a trigger.

According to the CDC, one fifth of American adults live with chronic pain, and women are affected more than men. Do men and women simply vary in how much pain they can handle? Or is there some deeper biological explanation? The short answer is it's a little of both. But understanding the biological differences can enable researchers to develop more effective treatments.

While studies in animals are straightforward (they either respond to pain or they don't), humans are more complex. Social and psychological factors can affect the outcome. For example, one Florida study found that gender role expectations influenced pain sensitivity.

"If you are a young male and you believe very strongly that men are tougher than women, you will have a much higher threshold and will be less sensitive to pain," says Robert Sorge, an associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham whose lab researches the immune system's involvement in pain and addiction.

He also notes, "We looked at transgender women and their pain sensitivity in comparison to cis men and women. They show very similar pain sensitivity to cis women, so that may reduce the impact of genetic sex in terms of what underlies that sensitivity."

But the difference goes deeper than gender expectations. There are biological differences as well. In 2015, Sorge and his team discovered that pain stimuli activated different immune cells in male and female rodents and that the presence of testosterone seemed to be a factor in the response.

More recently, Ted Price, professor of neuroscience at University of Texas, Dallas, examined pain at a genetic level, specifically looking at the patterns of RNA, which are single-stranded molecules that act as a messenger for DNA. Price noted that there were differences in these patterns that coincided with whether an individual experienced pain.

Price explains, "Every cell in your body has DNA, but the RNA that is in the cells is different for every cell type. The RNA in any particular cell type, like a neuron, can change as a result of some environmental influence like an injury. We found a number of genes that are potentially causative factors for neuropathic pain. Those, interestingly, seemed to be different between men and women."

Differences in treatment also affect pain response. Sorge says, "Women are experiencing more pain dismissal and more hostility when they report chronic pain. Women are more likely to have their pain associated with psychological issues." He adds that this dismissal may require women to exaggerate symptoms in order to be believed.

This can impact pain management. "Women are more likely to be prescribed and to use opioids," says Dr. Roger B. Fillingim, Director of Pain Research and Intervention Center of Excellence at the University of Florida. Yet, when self-administering pain meds, "women used significantly less opioids after surgery than did men." He also points out that "men are at greater risk for dose escalation and for opioid-related death than are women. So even though more women are using opioids, men are more likely to die from opioid-related causes."

Price acknowledges that other drugs treat pain, but "unfortunately, for chronic pain, none of these drugs work very well. We haven't yet made classes of drugs that really target the underlying mechanism that causes people to have chronic pain."

New drugs are now being developed that "might be particularly efficacious in women's chronic pain."

Sorge points out that there are many variables in pain conditions, so drugs that work for one may be ineffective for another. "With all that we know now about genetics and the immune system, I think the future of pain medicine is more precision-based, where based on your genetics, your immune status, your history, we may eventually get to the point where we can say [certain] drugs have a much bigger chance of working for you."

It will take some time for these new discoveries to translate into effective treatments, but Price says, "I'm excited about the opportunities. DNA and RNA sequencing totally changes our ability to make these therapeutics. I'm very hopeful." New drugs are now being developed that "might be particularly efficacious in women's chronic pain," he says, because they target specific receptors that seem to be involved when only women experience pain.

Earlier this year, three such drugs were approved to treat migraines; Rotondi recently began taking one. For Rotondi, improved treatments would allow her to "show up for life. For me," she says, "it would mean freedom."