Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

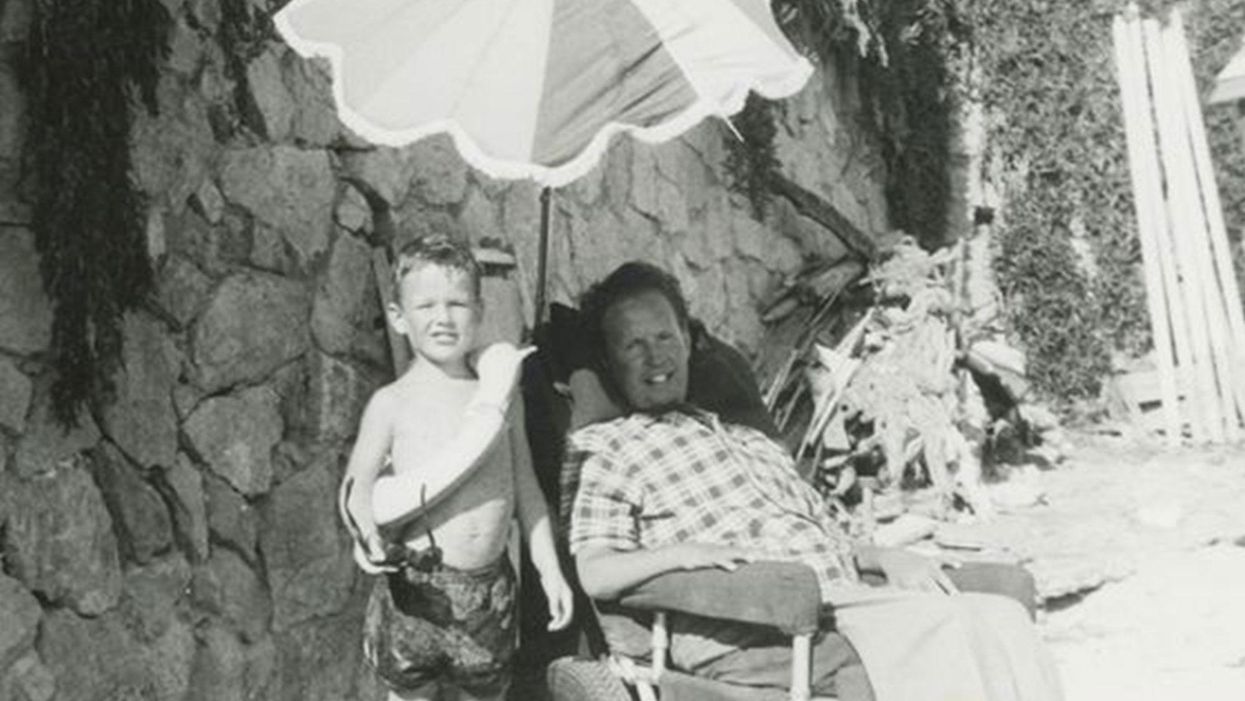

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

Dadbot, Wifebot, Friendbot: The Future of Memorializing Avatars

In 2015, about a year before he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, John Vlahos posed for a picture with his son, James.

In 2016, when my family found out that my father was dying from cancer, I did something that at the time felt completely obvious: I started building a chatbot replica of him.

I simply wanted to create an interactive way to share key parts of his life story.

I was not under any delusion that the Dadbot, as I soon began calling it, would be a true avatar of him. From my research about the voice computing revolution—Siri, Alexa, the Google Assistant—I knew that fully humanlike AIs, like you see in the movies, were a vast ways from technological reality. Replicating my dad in any real sense was never the goal, anyway; that notion gave me the creeps.

Instead, I simply wanted to create an interactive way to share key parts of his life story: facts about his ancestors in Greece. Memories from growing up. Stories about his hobbies, family life, and career. And I wanted the Dadbot, which sent text messages and audio clips over Facebook Messenger, to remind me of his personality—warm, erudite, and funny. So I programmed it to use his distinctive phrasings; to tell a few of his signature jokes and sing his favorite songs.

While creating the Dadbot, a laborious undertaking that sprawled into 2017, I fixated on two things. The first was getting the programming right, which I did using a conversational agent authoring platform called PullString. The second, far more wrenching concern was my father's health. Failing to improve after chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and steadily losing energy, weight, and the animating sparkle of life, he died on February 9.

John Vlahos at a family reunion in the summer of 2016, a few months after his cancer diagnosis.

(Courtesy James Vlahos)

After a magazine article that I wrote about the Dadbot came out in the summer of 2017, messages poured in from readers. While most people simply expressed sympathy, some conveyed a more urgent message: They wanted their own memorializing chatbots. One man implored me to make a bot for him; he had been diagnosed with cancer and wanted his six-month-old daughter to have a way to remember him. A technology entrepreneur needed advice on replicating what I did for her father, who had stage IV cancer. And a teacher in India asked me to engineer a conversational replica of her son, who had recently been struck and killed by a bus.

Journalists from around the world also got in touch for interviews, and they inevitably came around to the same question. Will virtual immortality, they asked, ever become a business?

The prospect of this happening had never crossed my mind. I was consumed by my father's struggle and my own grief. But the notion has since become head-slappingly obvious. I am not the only person to confront the loss of a loved one; the experience is universal. And I am not alone in craving a way to keep memories alive. Of course people like the ones who wrote me will get Dadbots, Mombots, and Childbots of their own. If a moonlighting writer like me can create a minimum viable product, then a company employing actual computer scientists could do much more.

But this prospect raises unanswered and unsettling questions. For businesses, profit, and not some deeply personal mission, will be the motivation. This shift will raise issues that I didn't have to confront. To make money, a virtual immortality company could follow the lucrative but controversial business model that has worked so well for Google and Facebook. To wit, a company could provide the memorializing chatbot for free and then find ways to monetize the attention and data of whoever communicated with it. Given the copious amount of personal information flowing back and forth in conversations with replica bots, this would be a data gold mine for the company—and a massive privacy risk for users.

Virtual immortality as commercial product will doubtless become more sophisticated.

Alternately, a company could charge for memorializing avatars, perhaps with an annual subscription fee. This would put the business in a powerful position. Imagine the fee getting hiked each year. A customer like me would find himself facing a terrible decision—grit my teeth and keep paying, or be forced to pull the plug on the best, closest reminder of a loved one that I have. The same person would effectively wind up dying twice.

Another way that a beloved digital avatar could die is if the company that creates it ceases to exist. This is no mere academic concern for me: Earlier this year, PullString was swallowed up by Apple. I'm still able to access the Dadbot on my own computer, fortunately, but the acquisition means that other friends and family members can no longer chat with him remotely.

Startups like PullString, of course, are characterized by impermanence; they tend to get snapped up by bigger companies or run out of venture capital and fold. But even if big players like, say, Facebook or Google get into the virtual immortality game, we can't count on them existing even a few decades from now, which means that the avatars enabled by their technology would die, too.

The permanence problem is the biggest hurdle faced by the fledgling enterprise of virtual immortality. So some entrepreneurs are attempting to enable avatars whose existence isn't reliant upon any one company or set of computer servers. "By leveraging the power of blockchain and decentralized software to replicate information, we help users create avatars that live on forever," says Alex Roy, the founder and CEO of the startup Everlife.ai. But until this type of solution exists, give props to conventional technology for preserving memories: printed photos and words on paper can last for centuries.

The fidelity of avatars—just how lifelike they are—also raises serious concerns. Before I started creating the Dadbot, I worried that the tech might be just good enough to remind my family of the man it emulated, but so far off from my real father that it gave us all the creeps. But because the Dadbot was a simple chatbot and not some all-knowing AI, and because the interface was a messaging app, there was no danger of him encroaching on the reality of my actual dad.

But virtual immortality as commercial product will doubtless become more sophisticated. Avatars will have brains built by teams of computer scientists employing the latest techniques in conversational AI. The replicas will not just text but also speak, using synthetic voices that emulate the ones of the people being memorialized. They may even come to life as animated clones on computer screens or in 3D with the help of virtual reality headsets.

What fascinates me is how technology can help to preserve the past—genuine facts and memories from peoples' lives.

These are all lines that I don't personally want to cross; replicating my dad was never the goal. I also never aspired to have some synthetic version of him that continued to exist in the present, capable of acquiring knowledge about the world or my life and of reacting to it in real time.

Instead, what fascinates me is how technology can help to preserve the past—genuine facts and memories from people's lives—and their actual voices so that their stories can be shared interactively after they have gone. I'm working on ideas for doing this via voice computing platforms like Alexa and Assistant, and while I don't have all of the answers yet, I'm excited to figure out what might be possible.

[Adapted from Talk to Me: How Voice Computing Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Think (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 26, 2019).]

The Best Kept Secret on the International Space Station

Rendering of Space Tango ST-42 autonomous commercial manufacturing platform in Low Earth Orbit. (Courtesy Space Tango)

[Editor's Note: This video is the second of a five-part series titled "The Future Is Now: The Revolutionary Power of Stem Cell Research." Produced in partnership with the Regenerative Medicine Foundation, and filmed at the annual 2019 World Stem Cell Summit, this series illustrates how stem cell research will profoundly impact life on earth.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.