Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

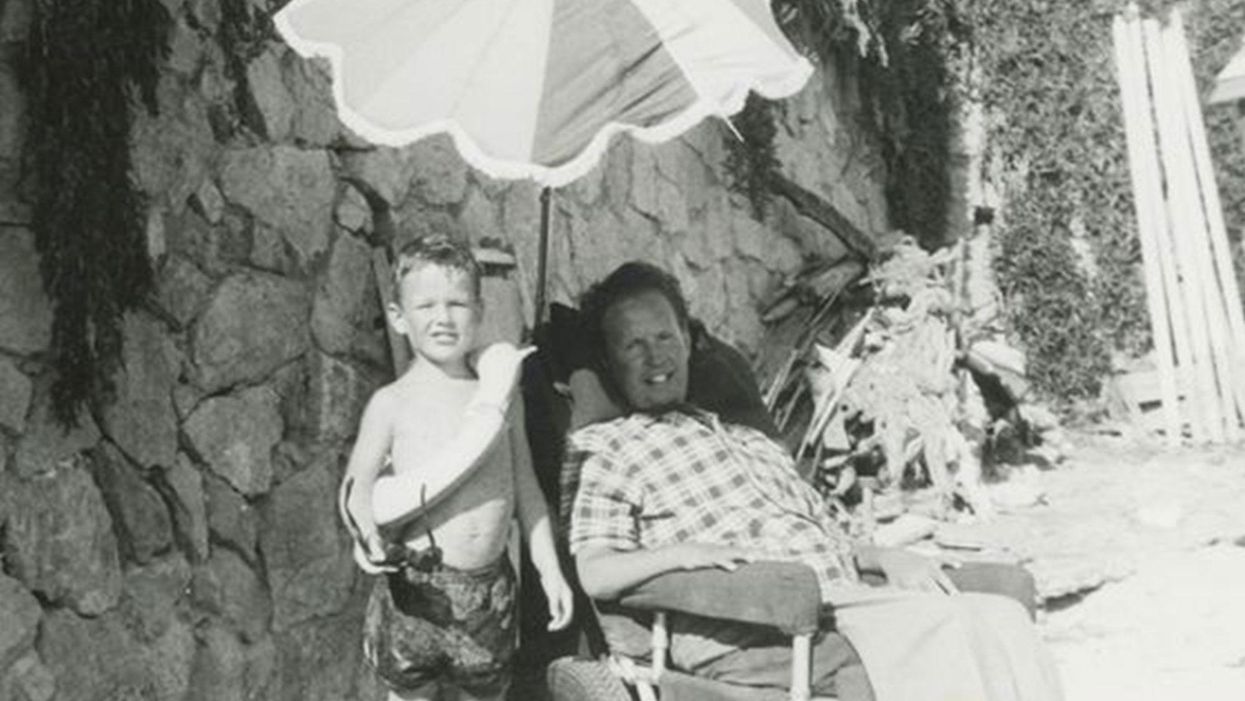

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

“Young Blood” Transfusions Are Not Ready For Primetime – Yet

A young woman donates blood.

The world of dementia research erupted into cheers when news of the first real victory in a clinical trial against Alzheimer's Disease in over a decade was revealed last October.

By connecting the circulatory systems of a young and an old mouse, the regenerative potential of the young mouse decreased, and the old mouse became healthier.

Alzheimer's treatments have been famously difficult to develop; 99 percent of the 200-plus such clinical trials since 2000 have utterly failed. Even the few slight successes have failed to produce what is called 'disease modifying' agents that really help people with the disease. This makes the success, by the midsize Spanish pharma company Grifols, worthy of special attention.

However, the specifics of the Grifols treatment, a process called plasmapheresis, are atypical for another reason - they did not give patients a small molecule or an elaborate gene therapy, but rather simply the most common component of normal human blood plasma, a protein called albumin. A large portion of the patients' normal plasma was removed, and then a sterile solution of albumin was infused back into them to keep their overall blood volume relatively constant.

So why does replacing Alzheimer's patients' plasma with albumin seem to help their brains? One theory is that the action is direct. Alzheimer's patients have low levels of serum albumin, which is needed to clear out the plaques of amyloid that slowly build up in the brain. Supplementing those patients with extra albumin boosts their ability to clear the plaques and improves brain health. However, there is also evidence suggesting that the problem may be something present in the plasma of the sick person and pulling their plasma out and replacing it with a filler, like an albumin solution, may be what creates the purported benefit.

This scientific question is the tip of an iceberg that goes far beyond Alzheimer's Disease and albumin, to a debate that has been waged on the pages of scientific journals about the secrets of using young, healthy blood to extend youth and health.

This debate started long before the Grifols data was released, in 2014 when a group of researchers at Stanford found that by connecting the circulatory systems of a young and an old mouse, the regenerative potential of the young mouse decreased, and the old mouse became healthier. There was something either present in young blood that allowed tissues to regenerate, or something present in old blood that prevented regeneration. Whatever the biological reason, the effects in the experiment were extraordinary, providing a startling boost in health in the older mouse.

After the initial findings, multiple research groups got to work trying to identify the "active factor" of regeneration (or the inhibitor of that regeneration). They soon uncovered a variety of compounds such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), CCL11, and GDF11, but none seemed to provide all the answers researchers were hoping for, with a number of high-profile retractions based on unsound experimental practices, or inconclusive data.

Years of research later, the simplest conclusion is that the story of plasma regeneration is not simple - there isn't a switch in our blood we can flip to turn back our biological clocks. That said, these hypotheses are far from dead, and many researchers continue to explore the possibility of using the rejuvenating ability of youthful plasma to treat a variety of diseases of aging.

But the bold claims of improved vigor thanks to young blood are so far unsupported by clinical evidence.

The data remain intriguing because of the astounding results from the conjoined circulatory system experiments. The current surge in interest in studying the biology of aging is likely to produce a new crop of interesting results in the next few years. Both CCL11 and GDF11 are being researched as potential drug targets by two startups, Alkahest and Elevian, respectively.

Without clarity on a single active factor driving rejuvenation, it's tempting to try a simpler approach: taking actual blood plasma provided by young people and infusing it into elderly subjects. This is what at least one startup company, Ambrosia, is now offering in five commercial clinics across the U.S. -- for $8,000 a liter.

By using whole plasma, the idea is to sidestep our ignorance, reaping the benefits of young plasma transfusion without knowing exactly what the active factors are that make the treatment work in mice. This space has attracted both established players in the plasmapheresis field – Alkahest and Grifols have teamed up to test fractions of whole plasma in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's – but also direct-to-consumer operations like Ambrosia that just want to offer patients access to treatments without regulatory oversight.

But the bold claims of improved vigor thanks to young blood are so far unsupported by clinical evidence. We simply haven't performed trials to test whether dosing a mostly healthy person with plasma can slow down aging, at least not yet. There is some evidence that plasma replacement works in mice, yes, but those experiments are all done in very different systems than what a human receiving young plasma might experience. To date, I have not seen any plasma transfusion clinic doing young blood plasmapheresis propose a clinical trial that is anything more than a shallow advertisement for their procedures.

The efforts I have seen to perform prophylactic plasmapheresis will fail to impact societal health. Without clearly defined endpoints and proper clinical trials, we won't know whether the procedure really lowers the risk of disease or helps with conditions of aging. So even if their hypothesis is correct, the lack of strong evidence to fall back on means that the procedure will never spread beyond the fringe groups willing to take the risk. If their hypothesis is wrong, then people are paying a huge amount of money for false hope, just as they do, sadly, at the phony stem cell clinics that started popping up all through the 2000s when stem cell hype was at its peak.

Until then, prophylactic plasma transfusions will be the domain of the optimistic and the gullible.

The real progress in the field will be made slowly, using carefully defined products either directly isolated from blood or targeting a bloodborne factor, just as the serious pharma and biotech players are doing already.

The field will progress in stages, first creating and carefully testing treatments for well-defined diseases, and only then will it progress to large-scale clinical trials in relatively healthy people to look for the prevention of disease. Most of us will choose to wait for this second stage of trials before undergoing any new treatments. Until then, prophylactic plasma transfusions will be the domain of the optimistic and the gullible.

Who’s Responsible for Curbing the Teen Vaping Epidemic?

A teenage girl vaping in a park.

E-cigarettes are big business. In 2017, American consumers bought more than $250 million in vapes and juice-filled pods, and spent $1 billion in 2018. By 2023, the global market could be worth $44 billion a year.

"My nine-year-old actually knows what Juuling is. In many cases the [school] bathroom is now referred to as 'the Juuling room.'"

Investors are trying to capitalize on the phenomenal growth. In July 2018, Juul Labs, the company that owns 70 percent of the U.S. e-cigarette market share, raised $1.25 billion at a $16 billion valuation, then sold a 35 percent stake to Phillip Morris USA owner Altria Group in December. The second transaction valued the company at $38 billion. While the traditional tobacco market remains much larger, it's projected to grow at less than two percent a year, making the attractiveness of the rapidly expanding e-cigarette market obvious.

While Juul and other e-cigarette manufacturers argue that their products help adults quit smoking – and there's some research to back this narrative up – much of the growth has been driven by children and teenagers. One CDC study showed a 48 percent rise in e-cigarette use by middle schoolers and a 78 percent increase by high schoolers between 2017 and 2018, a jump from 1.5 million kids to 3.6 million. In response to the study, F.D.A. Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said, "We see clear signs that youth use of electronic cigarettes has reached an epidemic proportion."

Another study found that teenagers between 15 and 17 were 16 times more likely to use Juul than people aged 25-34. In December, Surgeon General Jerome Adams said, "My nine-year-old actually knows what Juuling is. In many cases the [school] bathroom is now referred to as 'the Juuling room.'"

And the product is seriously addictive. A single Juul pod contains as much nicotine as a pack of 20 regular cigarettes. Considering that 90 percent of smokers are addicted by 18 years old, it's clear that steps need to be taken to combat the growing epidemic.

But who should take the lead? Juul and other e-cigarette companies? The F.D.A. and other government regulators? Schools? Parents?

The Surgeon General's website has a list of earnest possible texts that parents can send to their teens to dissuade them from Juuling, like: "Hope none of your friends use e-cigarettes around you. Even breathing the cloud they exhale can expose you to nicotine and chemicals that can be dangerous to your health." While parents can attempt to police their teens, many experts believe that the primary push should come at a federal level.

The regulation battle has already begun. In September, the F.D.A. announced that Juul had 60 days to show a plan that would prevent youth from getting their hands on the product. The result was for the company to announce that it wouldn't sell flavored pods in retail stores except for tobacco, menthol, and mint; Juul also shuttered its Instagram and Facebook accounts. These regulations mirrored an F.D.A. mandate two days later that required flavored e-cigarettes to be sold in closed-off areas. "This policy will make sure the fruity flavors are no longer accessible to kids in retail sites, plan and simple," Commissioner Gottlieb said when announcing the moves. "That's where they're getting access to the e-cigs and we intend to end those sales."

"There isn't a great history of the tobacco industry acting responsibly and being able to in any way police itself."

While so far, Gottlieb – who drew concerns about conflict of interest due to his past position as a board member at e-cigarette company, Kure – has pleased anti-smoking advocates with his efforts, some observers also argue that it needs to go further. "Overall, we didn't know what to expect when a new commissioner came in, but it's been quite refreshing how much attention has been paid to the tobacco industry by the F.D.A.," Robin Koval, CEO and president of Truth Initiative, said a day after the F.D.A. announced the proposed regulations. "It's important to have a start. I certainly want to give credit for that. But we were really hoping and feel that what was announced...doesn't go far enough."

The issue is the industry's inability or unwillingness to police itself in the past. Juul, however, claims that it's now proactively working to prevent young people from taking up its product. "Juul Labs and F.D.A. share a common goal – preventing youth from initiating on nicotine," a company representative said in an email. "To paraphrase Commissioner Gottlieb, we want to be the off-ramp for adult smokers to switch from cigarettes, not an on-ramp for America's youth to initiate on nicotine. We won't be successful in our mission to serve adult smokers if we don't narrow the on-ramp... Our intent was never to have youth use Juul products. But intent is not enough, the numbers are what matter, and the numbers tell us underage use of e-cigarette products is a problem. We must solve it."

Juul argues that its products help adults quit – even offering a calculator on the website showing how much people will save – and that it didn't target youth. But studies show otherwise. Furthermore, the youth smoking prevention curriculum the company released was poorly received. "It's what Philip Morris did years ago," said Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, a professor of pediatrics at Stanford who helped author a study on the program's faults. "They aren't talking about their named product. They are talking about vapes or e-cigarettes. Youth don't consider Juuls to be vapes or e-cigarettes. [Teens] don't talk about flavors. They don't talk about marketing. They did it to look good. But if you look at what [Juul] put together, it's a pretty awful curriculum that was put together pretty quickly."

The American Lung Association gave the FDA an "F" for failing to take mint and menthol e-cigs off the market, since those flavors remain popular with teens.

Add this all up, and in the end, it's hard to see the industry being able to police itself, critics say. Neither the past examples of other tobacco companies nor the present self-imposed regulations indicate that this will succeed.

"There isn't a great history of the tobacco industry acting responsibly and being able to in any way police itself," Koval said. "That job is best left to the F.D.A., and to the states and localities in what they can regulate and legislate to protect young people."

Halpern-Felsher agreed. "I think we need independent bodies. I really don't think that a voluntary ban or a regulation on the part of the industry is a good idea, nor do I think it will work," she said. "It's pretty much the same story, of repeating itself."

Just last week, the American Association of Pediatrics issued a new policy statement calling for the F.D.A. to immediately ban the sale of e-cigarettes to anyone under age 21 and to prohibit the online sale of vaping products and solutions, among other measures. And in its annual report, the American Lung Association gave the F.D.A. an "F" for failing to take mint and menthol e-cigs off the market, since those flavors remain popular with teens.

Few, if any people involved, want more regulation from the federal government. In an ideal world, this wouldn't be necessary. But many experts agree that it is. Anything else is just blowing smoke.