This App Helps Diagnose Rare Genetic Disorders from a Picture

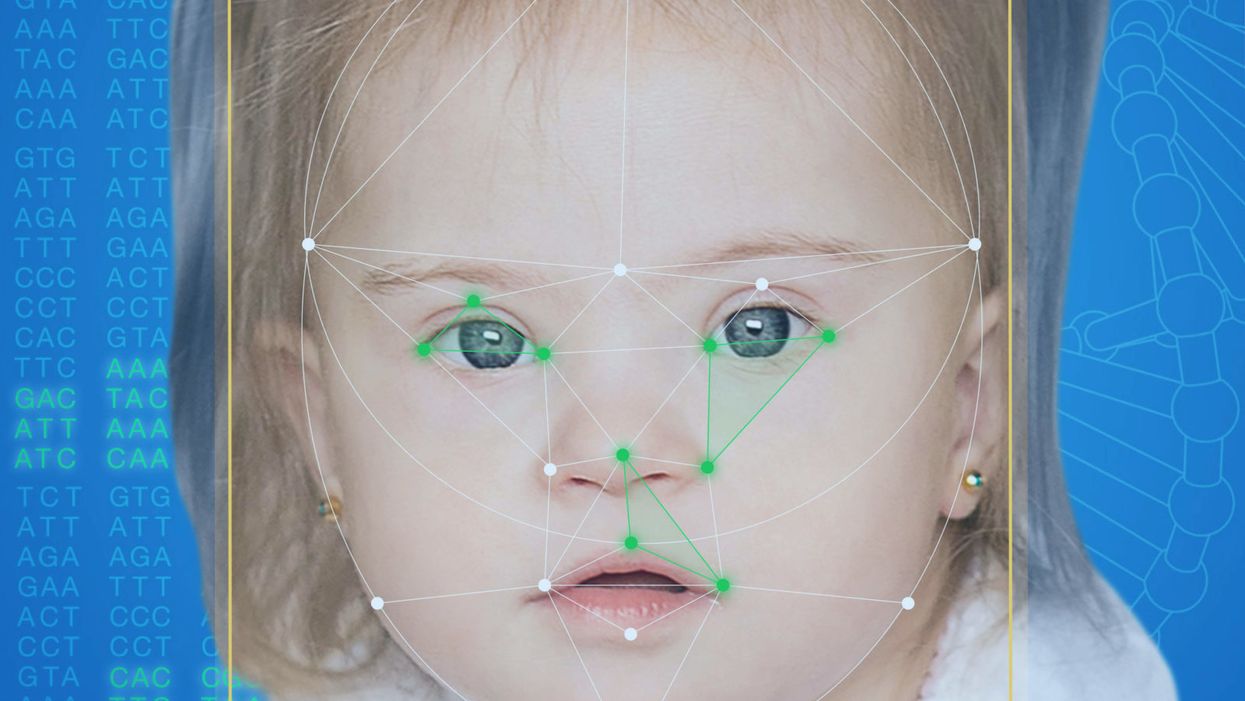

FDNA's Face2Gene technology analyzes patient biometric data using artificial intelligence, identifying correlations with disease-causing genetic variations.

Medical geneticist Omar Abdul-Rahman had a hunch. He thought that the three-year-old boy with deep-set eyes, a rounded nose, and uplifted earlobes might have Mowat-Wilson syndrome, but he'd never seen a patient with the rare disorder before.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test."

Rahman had already ordered genetic tests for three different conditions without any luck, and he didn't want to cost the family any more money—or hope—if he wasn't sure of the diagnosis. So he took a picture of the boy and uploaded the photo to Face2Gene, a diagnostic aid for rare genetic disorders. Sure enough, Mowat-Wilson came up as a potential match. The family agreed to one final genetic test, which was positive for the syndrome.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test,'" says Rahman, who is now the director of Genetic Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, but saw the boy when he was in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in 2012.

"Families who are dealing with undiagnosed diseases never know what's going to come around the corner, what other organ system might be a problem next week," Rahman says. With a diagnosis, "You don't have to wait for the other shoe to drop because now you know the extent of the condition."

A diagnosis is the first and most important step for patients to attain medical care. Disease prognosis, treatment plans, and emotional coping all stem from this critical phase. But diagnosis can also be the trickiest part of the process, particularly for rare disorders. According to one European survey, 40 percent of rare diseases are initially misdiagnosed.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing difficult disruptions due to misdiagnoses.

"Patients with rare diseases or genetic disorders go through a long period of diagnostic odyssey, and just putting a name to a syndrome or finding a diagnosis can be very helpful and relieve a lot of tension for the family," says Dekel Gelbman, CEO of FDNA.

Consequently, a misdiagnosis can be devastating for families. Money and time may have been wasted on fruitless treatments, while opportunities for potentially helpful therapies or clinical trials were missed. Parents led down the wrong path must change their expectations of their child's long-term prognosis and care. In addition, they may be misinformed regarding future decisions about family planning.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing these difficult disruptions by improving the accuracy and ease of diagnosing genetic disorders. Traditionally, doctors diagnose these types of conditions by identifying unique patterns of facial features, a practice called dysmorphology. Trained physicians can read a child's face like a map and detect any abnormal ridges or plateaus—wide-set eyes, broad forehead, flat nose, rotated ears—that, combined with other symptoms such as intellectual disability or abnormal height and weight, signify a specific genetic disorder.

These morphological changes can be subtle, though, and often only specialized medical geneticists are able to detect and interpret these facial clues. What's more, some genetic disorders are so rare that even a specialist may not have encountered it before, much less a general practitioner. Diagnosing rare conditions has improved thanks to genomic testing that can confirm (or refute) a doctor's suspicion. Yet with thousands of variants in each person's genome, identifying the culprit mutation or deletion can be extremely difficult if you don't know what you're looking for.

Facial recognition technology is trying to take some of the guesswork out of this process. Software such as the Face2Gene app use machine learning to compare a picture of a patient against images of thousands of disorders and come back with suggestions of possible diagnoses.

"This is a classic field for artificial intelligence because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

"When we met a geneticist for the first time we were pretty blown away with the fact that they actually use their own human pattern recognition" to diagnose patients, says Gelbman. "This is a classic field for AI [artificial intelligence], for machine learning because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

When a physician uploads a photo to the app, they are given a list of different diagnostic suggestions, each with a heat map to indicate how similar the facial features are to a classic representation of the syndrome. The physician can hone the suggestions by adding in other symptoms or family history. Gelbman emphasized that the app is a "search and reference tool" and should not "be used to diagnose or treat medical conditions." It is not approved by the FDA as a diagnostic.

"As a tool, we've all been waiting for this, something that can help everyone," says Julian Martinez-Agosto, an associate professor in human genetics and pediatrics at UCLA. He sees the greatest benefit of facial recognition technology in its ability to empower non-specialists to make a diagnosis. Many areas, including rural communities or resource-poor countries, do not have access to either medical geneticists trained in these types of diagnostics or genomic screens. Apps like Face2Gene can help guide a general practitioner or flag diseases they might not be familiar with.

One concern is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent.

Maximilian Muenke, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), agrees that in many countries, facial recognition programs could be the only way for a doctor to make a diagnosis.

"There are only geneticists in countries like the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan. In most countries, geneticists don't exist at all," Muenke says. "In Nigeria, the most populous country in all of Africa with 160 million people, there's not a single clinical geneticist. So in a country like that, facial recognition programs will be sought after and will be extremely useful to help make a diagnosis to the non-geneticists."

One concern about providing this type of technology to a global population is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent. However, the defining facial features of some of these disorders manifest differently across ethnicities, leaving clinicians from other geographic regions at a disadvantage.

"Every syndrome is either more easy or more difficult to detect in people from different geographic backgrounds," explains Muenke. For example, "in some countries of Southeast Asia, the eyes are slanted upward, and that happens to be one of the findings that occurs mostly with children with Down Syndrome. So then it might be more difficult for some individuals to recognize Down Syndrome in children from Southeast Asia."

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children.

To combat this issue, Muenke helped develop the Atlas of Human Malformation Syndromes, a database that incorporates descriptions and pictures of patients from every continent. By providing examples of rare genetic disorders in children from outside of the United States and Europe, Muenke hopes to provide clinicians with a better understanding of what to look for in each condition, regardless of where they practice.

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children. Face2Gene is free to download in the app store, although users must be authenticated by the company as a healthcare professional before they can access the database. The NHGRI Atlas can be accessed by anyone through their website. However, Martinez and Muenke say parents already use Google and WebMD to look up their child's symptoms; facial recognition programs and databases are just an extension of that trend. In fact, Martinez says, "Empowering families is another way to facilitate access to care. Some families live in rural areas and have no access to geneticists. If they can use software to get a diagnosis and then contact someone at a large hospital, it can help facilitate the process."

Martinez also says the app could go further by providing greater transparency about how the program makes its assessments. Giving clinicians feedback about why a diagnosis fits certain facial features would offer a valuable teaching opportunity in addition to a diagnostic aid.

Both Martinez and Muenke think the technology is an innovation that could vastly benefit patients. "In the beginning, I was quite skeptical and I could not believe that a machine could replace a human," says Muenke. "However, I am a convert that it actually can help tremendously in making a diagnosis. I think there is a place for facial recognition programs, and I am a firm believer that this will spread over the next five years."

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.