Short Story Contest Winner: "The Gerry Program"

A father and son gaze at the ducks in a lake.

It's an odd sensation knowing you're going to die, but it was a feeling Gerry Ferguson had become relatively acquainted with over the past two years. What most perplexed the terminally ill, he observed, was not the concept of death so much as the continuation of all other life.

Gerry's secret project had been in the works for two years now, ever since they found the growth.

Who will mourn me when I'm gone? What trait or idiosyncrasy will people most recall? Will I still be talked of, 100 years from now?

But Gerry didn't worry about these questions. He was comfortable that his legacy would live on, in one form or another. From his cozy flat in the west end of Glasgow, Gerry had managed to put his affairs in order and still find time for small joys.

Feeding the geese in summer at the park just down from his house, reading classics from the teeming bookcase in the living room, talking with his son Michael on Skype. It was Michael who had first suggested reading some of the new works of non-fiction that now littered the large oak desk in Gerry's study.

He was just finishing 'The Master Algorithm' when his shabby grandfather clock chimed six o'clock. Time to call Michael. Crammed into his tiny study, Gerry pulled his computer's webcam close and waved at Michael's smiling face.

"Hi Dad! How're you today?"

"I'm alright, son. How're things in sunny Australia?"

"Hot as always. How's things in Scotland?"

"I'd 'ave more chance gettin' a tan from this computer screen than I do goin' out there."

Michael chuckled. He's got that hearty Ferguson laugh, Gerry thought.

"How's the project coming along?" Michael asked. "Am I going to see it one of these days?"

"Of course," grinned Gerry, "I designed it for you."

Gerry's secret project had been in the works for two years now, ever since they found the growth. He had decided it was better not to tell Michael. He would only worry.

The two men chatted for hours. They discussed Michael's love life (or lack thereof), memories of days walking in the park, and their shared passion, the unending woes of Rangers Football Club. It wasn't until Michael said his goodbyes that Gerry noticed he'd been sitting in the dark for the best part of three hours, his mesh curtains casting a dim orange glow across the room from the street light outside. Time to get back to work.

*

Every night, Gerry sat at his computer, crawling forums, nourishing his project, feeding his knowledge and debating with other programmers. Even at age 82, Gerry knew more than most about algorithms. Never wanting to feel old, and with all the kids so adept at this digital stuff, Gerry figured he should give the Internet a try too. Besides, it kept his brain active and restored some of the sociability he'd lost in the previous decades as old friends passed away and the physical scope of his world contracted.

This night, like every night, Gerry worked away into the wee hours. His back would ache come morning, but this was the only time he truly felt alive these days. From his snug red brick home in Scotland, Gerry could share thoughts and information with strangers from all over the world. It truly was a miracle of modern science!

*

The next day, Gerry woke to the warm amber sun seeping in between a crack in the curtains. Like every morning, his thoughts took a little time to come into focus. Instinctively his hand went to the other side of the bed. Nobody there. Of course; she was gone. Rita, the sweetest woman he'd ever known. Four years this spring, God rest her soul.

Puttering around the cramped kitchen, Gerry heard a knock at the door. Who could that be? He could see two women standing in the hallway, their bodies contorted in the fisheye glass of the peephole. One looked familiar, but Gerry couldn't be sure. He fiddled with the locks and pulled the door open.

"Hi Gerry. How are you today?"

"Fine, thanks," he muttered, still searching his mind for where he'd seen her face before.

Noting the confusion in his eyes, the woman proffered a hand. "Alice, Alice Corgan. I pop round every now and again to check on you."

It clicked. "Ah aye! Come in, come in. Lemme get ya a cuppa." Gerry turned and shuffled into the flat.

As Gerry set about his tiny kitchen, Alice called from the living room, "This is Mandy. She's a care worker too. She's going to pay you occasional visits if that's alright with you."

Gerry poked his head around the doorway. "I'll always welcome a beautiful young lady in ma home. Though, I've tae warn you I'm a married man, so no funny business." He winked and ducked back into the kitchen.

Alice turned to Mandy with a grin. "He's a good man, our Gerry. You'll get along just fine." She lowered her voice. "As I said, with the Alzheimer's, he has to be reminded to take his medication, but he's still mostly self-sufficient. We installed a medi-bot to remind him every day and dispense the pills. If he doesn't respond, we'll get a message to send someone over."

Mandy nodded and scribbled notes in a pad.

"When I'm gone, Michael will have somethin' to remember me by."

"Also, and this is something we've been working on for a few months now, Gerry is convinced he has something…" her voice trailed off. "He thinks he has cancer. Now, while the Alzheimer's may affect his day-to-day life, it's not at a stage where he needs to be taken into care. The last time we went for a checkup, the doctor couldn't find any sign of cancer. I think it stems from--"

Gerry shouted from the other room: "Does the young lady take sugar?"

"No, I'm fine thanks," Mandy called back.

"Of course you don't," smiled Gerry. "Young lady like yersel' is sweet enough."

*

The following week, Mandy arrived early at Gerry's. He looked unsure at first, but he invited her in.

Sitting on the sofa nurturing a cup of tea, Alice tried to keep things light. "So what do you do in your spare time, Gerry?"

"I've got nothing but spare time these days, even if it's running a little low."

"Do you have any hobbies?"

"Yes actually." Gerry smiled. "I'm makin' a computer program."

Alice was taken aback. She knew very little about computers herself. "What's the program for?" she asked.

"Well, despite ma appearance, I'm no spring chicken. I know I don't have much time left. Ma son, he lives down in Australia now, he worked on a computer program that uses AI - that's artificial intelligence - to imitate a person."

Alice still looked confused, so Gerry pressed on.

"Well, I know I've not long left, so I've been usin' this open source code to make ma own for when I'm gone. I've already written all the code. Now I just have to add the things that make it seem like me. I can upload audio, text, even videos of masel'. That way, when I'm gone, Michael will have somethin' to remember me by."

Mandy sat there, stunned. She had no idea anybody could do this, much less an octogenarian from his small, ramshackle flat in Glasgow.

"That's amazing Gerry. I'd love to see the real thing when you're done."

"O' course. I mean, it'll take time. There's so much to add, but I'll be happy to give a demonstration."

Mandy sat there and cradled her mug. Imagine, she thought, being able to preserve yourself, or at least some basic caricature of yourself, forever.

*

As the weeks went on, Gerry slowly added new shades to his coded double. Mandy would leaf through the dusty photo albums on Gerry's bookcase, pointing to photos and asking for the story behind each one. Gerry couldn't always remember but, when he could, the accompanying stories were often hilarious, incredible, and usually a little of both. As he vividly recounted tales of bombing missions over Burma, trips to the beach with a young Michael and, in one particularly interesting story, giving the finger to Margaret Thatcher, Mandy would diligently record them through a Dictaphone to be uploaded to the program.

Gerry loved the company, particularly when he could regale the young woman with tales of his son Michael. One day, as they sat on the sofa flicking through a box of trinkets from his days as a travelling salesman, Mandy asked why he didn't have a smartphone.

He shrugged. "If I'm out 'n about then I want to see the world, not some 2D version of it. Besides, there's nothin' on there for me."

Alice explained that you could get Skype on a smartphone: "You'd be able to talk with Michael and feed the geese at the park at the same time," she offered.

Gerry seemed interested but didn't mention it again.

"Only thing I'm worried about with ma computer," he remarked, "is if there's another power cut and I can't call Michael. There's been a few this year from the snow 'n I hate not bein' able to reach him."

"Well, if you ever want to use the Skype app on my phone to call him you're welcome," said Mandy. "After all, you just need to add him to my contacts."

Gerry was flattered. "That's a relief, knowing I won't miss out on calling Michael if the computer goes bust."

*

Then, in early spring, just as the first green buds burst forth from the bare branches, Gerry asked Mandy to come by. "Bring that Alice girl if ya can - I know she's excited to see this too."

The next day, Mandy and Alice dutifully filed into the cramped study and sat down on rickety wooden chairs brought from the living room for this special occasion.

An image of Gerry, somewhat younger than the man himself, flashed up on the screen.

With a dramatic throat clearing, Gerry opened the program on his computer. An image of Gerry, somewhat younger than the man himself, flashed up on the screen.

The room was silent.

"Hiya Michael!" AI Gerry blurted. The real Gerry looked flustered and clicked around the screen. "I forgot to put the facial recognition on. Michael's just the go-to name when it doesn't recognize a face." His voice lilted with anxious excitement. "This is Alice," Gerry said proudly to the camera, pointing at Alice, "and this is Mandy."

AI Gerry didn't take his eyes from real Gerry, but grinned. "Hello, Alice. Hiya Mandy." The voice was definitely his, even if the flow of speech was slightly disjointed.

"Hi," Alice and Mandy stuttered.

Gerry beamed at both of them. His eyes flitted between the girls and the screen, perhaps nervous that his digital counterpart wasn't as polished as they'd been expecting.

"You can ask him almost anything. He's not as advanced as the ones they're making in the big studios, but I think Michael will like him."

Alice and Mandy gathered closer to the monitor. A mute Gerry grinned back from the screen. Sitting in his wooden chair, the real Gerry turned to his AI twin and began chattering away: "So, what do you think o' the place? Not bad eh?"

"Oh aye, like what you've done wi' it," said AI Gerry.

"Gerry," Alice cut in. "What did you say about Michael there?"

"Ah, I made this for him. After all, it's the kind o' thing his studio was doin'. I had to clear some space to upload it 'n show you guys, so I had to remove Skype for now, but Michael won't mind. Anyway, Mandy's gonna let me Skype him from her phone."

Mandy pulled her phone out and smiled. "Aye, he'll be able to chat with two Gerry's."

Alice grabbed Mandy by the arm: "What did you tell him?" she whispered, her eyes wide.

"I told him he can use my phone if he wants to Skype Michael. Is that okay?"

Alice turned to Gerry, who was chattering away with his computerized clone. "Gerry, we'll just be one second, I need to discuss something with Mandy."

"Righto," he nodded.

Outside the room, Alice paced up and down the narrow hallway.

Mandy could see how flustered she was. "What's wrong? Don't you like the chatbot? I think it's kinda c-"

"Michael's dead," Alice spluttered.

"What do you mean? He talks to him all the time."

Alice sighed. "He doesn't talk to Michael. See, a few years back, Michael found out he had cancer. He worked for this company that did AI chatbot stuff. When he knew he was dying he--" she groped in the air for the words-- "he built this chatbot thing for Gerry, some kind of super-advanced AI. Gerry had just been diagnosed with Alzheimer's and I guess Michael was worried Gerry would forget him. He designed the chatbot to say he was in Australia to explain why he couldn't visit."

"That's awful," Mandy granted, "but I don't get what the problem is. I mean, surely he can show the AI Michael his own chatbot?"

"No, because you can't get the AI Michael on Skype. Michael just designed the program to look like Skype."

"But then--" Mandy went silent.

"Michael uploaded the entire AI to Gerry's computer before his death. Gerry didn't delete Skype. He deleted the AI Michael."

"So… that's it? He-he's gone?" Mandy's voice cracked. "He can't just be gone, surely he can't?"

The women stood staring at each other. They looked to the door of the study. They could still hear Gerry, gabbing away with his cybercopy.

"I can't go back in there," muttered Mandy. Her voice wavered as she tried to stem the misery rising in her throat.

Alice shook her head and paced the floor. She stopped and stared at Mandy with grim resignation. "We don't have a choice."

When they returned, Gerry was still happily chatting away.

"Hiya girls. Ya wanna ask my handsome twin any other questions? If not, we could get Michael on the phone?"

Neither woman spoke. Gerry clapped his hands and turned gaily to the monitor again: "I cannae wait for ya t'meet him, Gerry. He's gonna be impressed wi' you."

Alice clasped her hands to her mouth. Tears welled in the women's eyes as they watched the old man converse with his digital copy. The heat of the room seemed to swell, becoming insufferable. Mandy couldn't take it anymore. She jumped up, bolted to the door and collapsed against a wall in the hallway. Alice perched on the edge of her seat in a dumb daze, praying for the floor to open and swallow the contents of the room whole.

Oblivious, Gerry and his echo babbled away, the blue glow of the screen illuminating his euphoric face. "Just wait until y'meet him Gerry, just wait."

Virtual Reality is Making Medical Care for Kids Less Scary and Painful

A patient at Children's Hospital Los Angeles (Courtesy of Children's Hospital Los Angeles) plus Bear Blast, developed by AppliedVR.

A blood draw is not normally a fun experience, but these days, virtual reality technology is changing that.

Instead of watching a needle go into his arm, a child wearing a VR headset at Children's Hospital Los Angeles can play a game throwing balls at cartoon bears. In Seattle, at the University of Washington, a burn patient can immerse herself in a soothing snow scene. And at the University of Miami Hospital, a five-minute skin biopsy can become an exciting ride at an amusement park.

VR is transforming once-frightening medical encounters for kids, from blood draws to biopsies to pre-surgical prep, into tolerable ones.

It's literally a game changer, says pediatric neurosurgeon Kurtis Auguste, who uses the tool to help explain pending operations to his young patients and their families. The virtual reality 3-D portrait of their brain is recreated from an MRI, originally to help plan the surgery. The image of normally bland tissue is painted with false colors to better see the boundaries and anomalies of each component. It can be rotated, viewed from every possible angle, zoomed in and out; incisions can be made and likely results anticipated. Auguste has extended its use to patients and families.

"The moment you put these headsets on the kids, we immediately have a link, because honestly, this is how they communicate with each other," says Auguste. "We're all sitting around the table playing games. It's really bridged the distance between me, the pediatric specialist, and my patients" at the Benioff Children's Hospital Oakland, now affiliated with the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

The VR experience engages people where they are, immersing them in the environment rather than lecturing them. And it seems to work in all environments, across age and cultural differences, leading to a better grasp of what will be undertaken. That understanding is crucial to meaningful informed consent for surgery. It is particularly relevant for safety-net hospitals, which includes most children's hospitals, because often members of the families were born elsewhere and may have limited understanding of English, not to mention advanced medicine.

Targeting pain

"We're trying to target ways that we can decrease pain, anxiety, fear – what people usually experience as a function of a needle," says Jeffrey Gold, a pioneer in adapting VR at Children's Hospital Los Angeles. He ran the pain clinic there and in 2004 initially focused on phlebotomy, simple blood draws. Many of their kids require frequent blood draws to monitor serious chronic conditions such as diabetes, HIV infection, sickle cell disease, and other conditions that affect the heart, liver, kidneys and other organs.

The scientific explanation of how VR works for pain relief draws upon two basic principles of brain function. The first is "top down inhibition," Gold explains. "We all have the inherent capacity to turn down signals once we determine that signal is no longer harmful, dangerous, hurtful, etc. That's how our brain operates on purpose. It's not just a distraction, it's actually your brain stopping the pain signal at the spinal cord before it can fire all the way up to the frontal lobe."

Second is the analgesic effect from endorphins. "If you're in a gaming environment, and you're having fun and you're laughing and giggling, you are actually releasing endorphins...a neurochemical reaction at the synaptic level of the brain," he says.

Part of what makes VR effective is "what's called a cognitive load, where you have to actually learn something and do something," says Gold. He has worked with developers on a game call Bear Blast, which has proven to be effective in a clinical trial for mitigating pain. But he emphasizes, it is not a one-size-fits all; the programs and patients need to be evaluated to understand what works best for each case.

Gold was a bit surprised to find that VR "actually facilitates quicker blood draws," because the staff doesn't have to manage the kids' anxiety, so "they require fewer needle sticks." The kids, parents, and staff were all having a good time, "and that's a big win when everybody is benefiting." About two years ago the hospital made VR an option that patients can request in the phlebotomy lab, and about half of kids age 4 and older choose to do so.

The technology "gets the kids engaged and performing the activity the way we want them to" to maximize recovery.

VR reduces or eliminates the need to use sedation or anesthesia, which carries a small but real risk of an adverse reaction. And important to parents, it eliminates the recovery time from using sedation, which shortens the visit and time missed from school and work.

A more intriguing question is whether reducing fear and anxiety in early-life experiences with the healthcare system through activities like VR will have a long-term affect on kids' attitudes toward medicine as they grow older. "If you're a screaming meemie when you come get your blood draw when you're five or seven, you're still that anxious adolescent or adult who is all quivering and sweating and avoiding healthcare," Gold says. "That's a longitudinal health outcome I'd love to get my hands on in 10-15 years from now."

Broader applications

Dermatologist Hadar Lev-Tov read about the use of VR to treat pain and decided to try it in his practice at the University of Miami Hospital. He thought, "OK, this is low risk, it's easy to do. So we got some equipment and got it done." It was so affordable he paid for it out of his own pocket, rather than wait to go through administrative channels. The results were so interesting that he decided to publish it as a series of case studies with a wide variety of patients and types of procedures.

Some of them, such as freezing off warts, are not particularly painful. "But there can be a lot of anxiety, especially for kids, which can be worse than pain and can disrupt the procedure." It can trigger a non-rational, primal fight or flight response in the limbic region of the brain.

Adults understand the need for a biopsy of a skin growth and tolerate what might be a momentary flick of pain. "But for a kid you think twice about a biopsy, both because it's a hassle and because it could be a traumatic event for a child," says Lev-Tov. VR has helped to allay such fears and improve medical care.

Integrating VR into practice has been relatively easy, primarily focusing on simple training for staff and ensuring that standard infection control practices are used in handling equipment that is used by different patients. More mundane issues are ensuring that the play back and wi-fi equipment are functioning properly. He has had a few complaints from kids when the procedure is competed and the VR is turned off prematurely, which is why he favors programs like a roller coaster ride that lasts about five minutes, ample time to take a biopsy or two.

The future is today

The pediatric neurosurgeon Auguste is collaborating with colleagues at Oakland Children's to expand use of VR into different areas of care. Cancer specialists often use a port, a bubble installed under the skin in the chest of the child, to administer chemotherapy. But the young patient's curiosity often draws their attention downward to the port and their chin can potentially contaminate or obstruct it, interfering with the procedure. So the team developed a VR game involving birds that requires players to move their heads upward, away from the port, improving administration of the drugs and reducing the risk of infection.

Innovative use of VR just may be one tool that actually makes kids eager to visit the doctor.

Other games are being developed for rehabilitation that require the use of specific nerve and muscle combinations. The technology "gets the kids engaged and performing the activity the way we want them to" to maximize recovery, Auguste explains. "We can monitor their progress by the score on the game, and if it plateaus, maybe switch to another game."

Another project is trying to ease the anxiety and confusion of the patient and family experience within the hospital itself. Hospital staff are creating a personalized VR introductory walking tour that leads from the parking garage through the maze of structures and corridors in the hospital complex to Dr. Auguste's office, phlebotomy, the MRI site, and other locations they might visit. The goal is to make them familiar with key landmarks before they even set foot in the facility. "So when they come the day of the visit they have already taken that exact same path, hopefully more than once."

"They don't miss their MRI appointment and therefore they don't miss their clinical appointment with me," says Auguste. It reduces patient anxiety about the encounter and from the hospital's perspective, it will reduce costs of missed and rescheduled visits simply because patients did not go to the right place at the right time.

The VR visit will be emailed to patients ahead of time and they can watch it on a smartphone installed in a disposable cardboard viewer. Oakland Children's hopes to have the system in place by early next year. Auguste says their goal in using VR, like other health care providers across the country, is "to streamline the entire patient experience."

Innovative use of VR just may be one tool that actually makes kids eager to visit the doctor. That would be a boon to kids, parents, and the health of America.

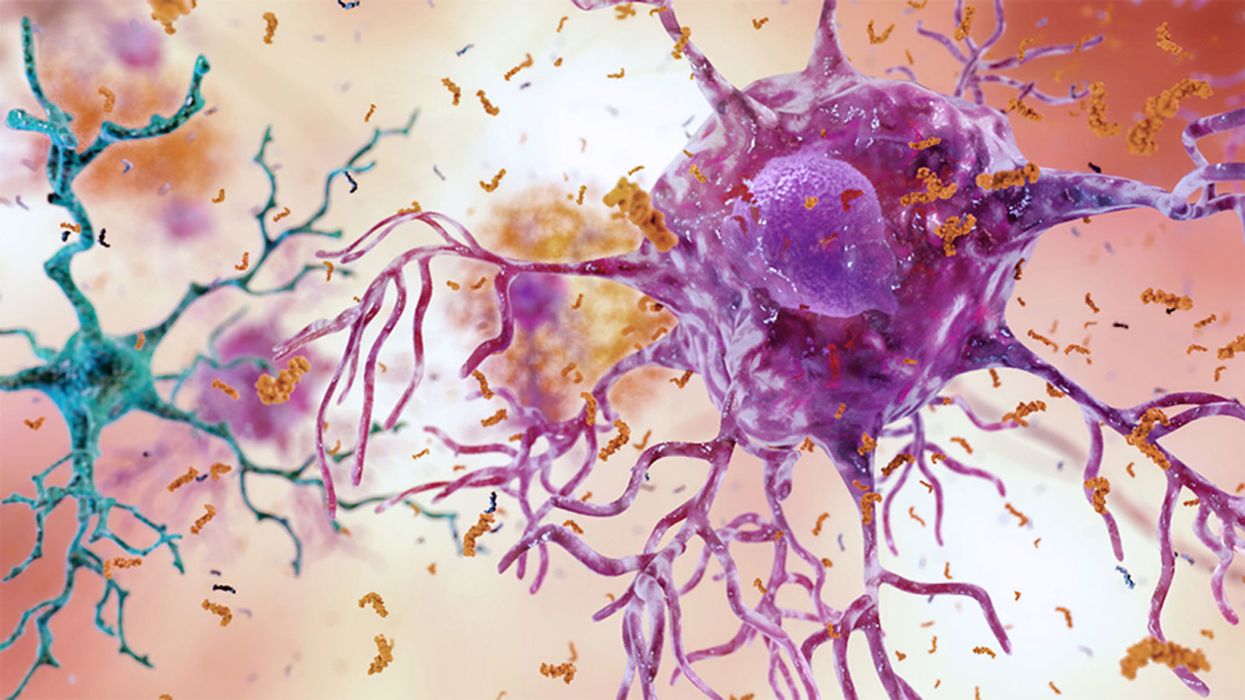

A Mother-and-Daughter Team Have Developed What May Be the World’s First Alzheimer’s Vaccine

Brain inflammation from Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's is a terrible disease that robs a person of their personality and memory before eventually leading to death. It's the sixth-largest killer in the U.S. and, currently, there are 5.8 million Americans living with the disease.

Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

It devastates people and families and it's estimated that Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia will cost the U.S. $290 billion dollars this year alone. It's estimated that it will become a trillion-dollar-a-year disease by 2050.

There have been over 200 unsuccessful attempts to find a cure for the disease and the clinical trial termination rate is 98 percent.

Alzheimer's is caused by plaque deposits that develop in brain tissue that become toxic to brain cells. One of the major hurdles to finding a cure for the disease is that it's impossible to clear out the deposits from the tissue. So scientists have turned their attention to early detection and prevention.

One very encouraging development has come out of the work done by Dr. Chang Yi Wang, PhD. Wang is a prolific bio-inventor; one of her biggest successes is developing a foot-and-mouth vaccine for pigs that has been administered more than three billion times.

Mei Mei Hu

Brainstorm Health / Flickr.

In January, United Neuroscience, a biotech company founded by Yi, her daughter Mei Mei Hu, and son-in-law, Louis Reese, announced the first results from a phase IIa clinical trial on UB-311, an Alzheimer's vaccine.

The vaccine has synthetic versions of amino acid chains that trigger antibodies to attack Alzheimer's protein the blood. Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

"We were able to generate some antibodies in all patients, which is unusual for vaccines," Yi told Wired. "We're talking about almost a 100 percent response rate. So far, we have seen an improvement in three out of three measurements of cognitive performance for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease."

The researchers also claim it can delay the onset of the disease by five years. While this would be a godsend for people with the disease and their families, according to Elle, it could also save Medicare and Medicaid more than $220 billion.

"You'd want to see larger numbers, but this looks like a beneficial treatment," James Brown, director of the Aston University Research Centre for Healthy Ageing, told Wired. "This looks like a silver bullet that can arrest or improve symptoms and, if it passes the next phase, it could be the best chance we've got."

"A word of caution is that it's a small study," says Drew Holzapfel, acting president of the nonprofit UsAgainstAlzheimer's, said according to Elle. "But the initial data is compelling."

The company is now working on its next clinical trial of the vaccine and while hopes are high, so is the pressure. The company has already invested $100 million developing its vaccine platform. According to Reese, the company's ultimate goal is to create a host of vaccines that will be administered to protect people from chronic illness.

"We have a 50-year vision -- to immuno-sculpt people against chronic illness and chronic aging with vaccines as prolific as vaccines for infectious diseases," he told Elle.

[Editor's Note: This article was originally published by Upworthy here and has been republished with permission.]