Short Story Contest Winner: "The Gerry Program"

A father and son gaze at the ducks in a lake.

It's an odd sensation knowing you're going to die, but it was a feeling Gerry Ferguson had become relatively acquainted with over the past two years. What most perplexed the terminally ill, he observed, was not the concept of death so much as the continuation of all other life.

Gerry's secret project had been in the works for two years now, ever since they found the growth.

Who will mourn me when I'm gone? What trait or idiosyncrasy will people most recall? Will I still be talked of, 100 years from now?

But Gerry didn't worry about these questions. He was comfortable that his legacy would live on, in one form or another. From his cozy flat in the west end of Glasgow, Gerry had managed to put his affairs in order and still find time for small joys.

Feeding the geese in summer at the park just down from his house, reading classics from the teeming bookcase in the living room, talking with his son Michael on Skype. It was Michael who had first suggested reading some of the new works of non-fiction that now littered the large oak desk in Gerry's study.

He was just finishing 'The Master Algorithm' when his shabby grandfather clock chimed six o'clock. Time to call Michael. Crammed into his tiny study, Gerry pulled his computer's webcam close and waved at Michael's smiling face.

"Hi Dad! How're you today?"

"I'm alright, son. How're things in sunny Australia?"

"Hot as always. How's things in Scotland?"

"I'd 'ave more chance gettin' a tan from this computer screen than I do goin' out there."

Michael chuckled. He's got that hearty Ferguson laugh, Gerry thought.

"How's the project coming along?" Michael asked. "Am I going to see it one of these days?"

"Of course," grinned Gerry, "I designed it for you."

Gerry's secret project had been in the works for two years now, ever since they found the growth. He had decided it was better not to tell Michael. He would only worry.

The two men chatted for hours. They discussed Michael's love life (or lack thereof), memories of days walking in the park, and their shared passion, the unending woes of Rangers Football Club. It wasn't until Michael said his goodbyes that Gerry noticed he'd been sitting in the dark for the best part of three hours, his mesh curtains casting a dim orange glow across the room from the street light outside. Time to get back to work.

*

Every night, Gerry sat at his computer, crawling forums, nourishing his project, feeding his knowledge and debating with other programmers. Even at age 82, Gerry knew more than most about algorithms. Never wanting to feel old, and with all the kids so adept at this digital stuff, Gerry figured he should give the Internet a try too. Besides, it kept his brain active and restored some of the sociability he'd lost in the previous decades as old friends passed away and the physical scope of his world contracted.

This night, like every night, Gerry worked away into the wee hours. His back would ache come morning, but this was the only time he truly felt alive these days. From his snug red brick home in Scotland, Gerry could share thoughts and information with strangers from all over the world. It truly was a miracle of modern science!

*

The next day, Gerry woke to the warm amber sun seeping in between a crack in the curtains. Like every morning, his thoughts took a little time to come into focus. Instinctively his hand went to the other side of the bed. Nobody there. Of course; she was gone. Rita, the sweetest woman he'd ever known. Four years this spring, God rest her soul.

Puttering around the cramped kitchen, Gerry heard a knock at the door. Who could that be? He could see two women standing in the hallway, their bodies contorted in the fisheye glass of the peephole. One looked familiar, but Gerry couldn't be sure. He fiddled with the locks and pulled the door open.

"Hi Gerry. How are you today?"

"Fine, thanks," he muttered, still searching his mind for where he'd seen her face before.

Noting the confusion in his eyes, the woman proffered a hand. "Alice, Alice Corgan. I pop round every now and again to check on you."

It clicked. "Ah aye! Come in, come in. Lemme get ya a cuppa." Gerry turned and shuffled into the flat.

As Gerry set about his tiny kitchen, Alice called from the living room, "This is Mandy. She's a care worker too. She's going to pay you occasional visits if that's alright with you."

Gerry poked his head around the doorway. "I'll always welcome a beautiful young lady in ma home. Though, I've tae warn you I'm a married man, so no funny business." He winked and ducked back into the kitchen.

Alice turned to Mandy with a grin. "He's a good man, our Gerry. You'll get along just fine." She lowered her voice. "As I said, with the Alzheimer's, he has to be reminded to take his medication, but he's still mostly self-sufficient. We installed a medi-bot to remind him every day and dispense the pills. If he doesn't respond, we'll get a message to send someone over."

Mandy nodded and scribbled notes in a pad.

"When I'm gone, Michael will have somethin' to remember me by."

"Also, and this is something we've been working on for a few months now, Gerry is convinced he has something…" her voice trailed off. "He thinks he has cancer. Now, while the Alzheimer's may affect his day-to-day life, it's not at a stage where he needs to be taken into care. The last time we went for a checkup, the doctor couldn't find any sign of cancer. I think it stems from--"

Gerry shouted from the other room: "Does the young lady take sugar?"

"No, I'm fine thanks," Mandy called back.

"Of course you don't," smiled Gerry. "Young lady like yersel' is sweet enough."

*

The following week, Mandy arrived early at Gerry's. He looked unsure at first, but he invited her in.

Sitting on the sofa nurturing a cup of tea, Alice tried to keep things light. "So what do you do in your spare time, Gerry?"

"I've got nothing but spare time these days, even if it's running a little low."

"Do you have any hobbies?"

"Yes actually." Gerry smiled. "I'm makin' a computer program."

Alice was taken aback. She knew very little about computers herself. "What's the program for?" she asked.

"Well, despite ma appearance, I'm no spring chicken. I know I don't have much time left. Ma son, he lives down in Australia now, he worked on a computer program that uses AI - that's artificial intelligence - to imitate a person."

Alice still looked confused, so Gerry pressed on.

"Well, I know I've not long left, so I've been usin' this open source code to make ma own for when I'm gone. I've already written all the code. Now I just have to add the things that make it seem like me. I can upload audio, text, even videos of masel'. That way, when I'm gone, Michael will have somethin' to remember me by."

Mandy sat there, stunned. She had no idea anybody could do this, much less an octogenarian from his small, ramshackle flat in Glasgow.

"That's amazing Gerry. I'd love to see the real thing when you're done."

"O' course. I mean, it'll take time. There's so much to add, but I'll be happy to give a demonstration."

Mandy sat there and cradled her mug. Imagine, she thought, being able to preserve yourself, or at least some basic caricature of yourself, forever.

*

As the weeks went on, Gerry slowly added new shades to his coded double. Mandy would leaf through the dusty photo albums on Gerry's bookcase, pointing to photos and asking for the story behind each one. Gerry couldn't always remember but, when he could, the accompanying stories were often hilarious, incredible, and usually a little of both. As he vividly recounted tales of bombing missions over Burma, trips to the beach with a young Michael and, in one particularly interesting story, giving the finger to Margaret Thatcher, Mandy would diligently record them through a Dictaphone to be uploaded to the program.

Gerry loved the company, particularly when he could regale the young woman with tales of his son Michael. One day, as they sat on the sofa flicking through a box of trinkets from his days as a travelling salesman, Mandy asked why he didn't have a smartphone.

He shrugged. "If I'm out 'n about then I want to see the world, not some 2D version of it. Besides, there's nothin' on there for me."

Alice explained that you could get Skype on a smartphone: "You'd be able to talk with Michael and feed the geese at the park at the same time," she offered.

Gerry seemed interested but didn't mention it again.

"Only thing I'm worried about with ma computer," he remarked, "is if there's another power cut and I can't call Michael. There's been a few this year from the snow 'n I hate not bein' able to reach him."

"Well, if you ever want to use the Skype app on my phone to call him you're welcome," said Mandy. "After all, you just need to add him to my contacts."

Gerry was flattered. "That's a relief, knowing I won't miss out on calling Michael if the computer goes bust."

*

Then, in early spring, just as the first green buds burst forth from the bare branches, Gerry asked Mandy to come by. "Bring that Alice girl if ya can - I know she's excited to see this too."

The next day, Mandy and Alice dutifully filed into the cramped study and sat down on rickety wooden chairs brought from the living room for this special occasion.

An image of Gerry, somewhat younger than the man himself, flashed up on the screen.

With a dramatic throat clearing, Gerry opened the program on his computer. An image of Gerry, somewhat younger than the man himself, flashed up on the screen.

The room was silent.

"Hiya Michael!" AI Gerry blurted. The real Gerry looked flustered and clicked around the screen. "I forgot to put the facial recognition on. Michael's just the go-to name when it doesn't recognize a face." His voice lilted with anxious excitement. "This is Alice," Gerry said proudly to the camera, pointing at Alice, "and this is Mandy."

AI Gerry didn't take his eyes from real Gerry, but grinned. "Hello, Alice. Hiya Mandy." The voice was definitely his, even if the flow of speech was slightly disjointed.

"Hi," Alice and Mandy stuttered.

Gerry beamed at both of them. His eyes flitted between the girls and the screen, perhaps nervous that his digital counterpart wasn't as polished as they'd been expecting.

"You can ask him almost anything. He's not as advanced as the ones they're making in the big studios, but I think Michael will like him."

Alice and Mandy gathered closer to the monitor. A mute Gerry grinned back from the screen. Sitting in his wooden chair, the real Gerry turned to his AI twin and began chattering away: "So, what do you think o' the place? Not bad eh?"

"Oh aye, like what you've done wi' it," said AI Gerry.

"Gerry," Alice cut in. "What did you say about Michael there?"

"Ah, I made this for him. After all, it's the kind o' thing his studio was doin'. I had to clear some space to upload it 'n show you guys, so I had to remove Skype for now, but Michael won't mind. Anyway, Mandy's gonna let me Skype him from her phone."

Mandy pulled her phone out and smiled. "Aye, he'll be able to chat with two Gerry's."

Alice grabbed Mandy by the arm: "What did you tell him?" she whispered, her eyes wide.

"I told him he can use my phone if he wants to Skype Michael. Is that okay?"

Alice turned to Gerry, who was chattering away with his computerized clone. "Gerry, we'll just be one second, I need to discuss something with Mandy."

"Righto," he nodded.

Outside the room, Alice paced up and down the narrow hallway.

Mandy could see how flustered she was. "What's wrong? Don't you like the chatbot? I think it's kinda c-"

"Michael's dead," Alice spluttered.

"What do you mean? He talks to him all the time."

Alice sighed. "He doesn't talk to Michael. See, a few years back, Michael found out he had cancer. He worked for this company that did AI chatbot stuff. When he knew he was dying he--" she groped in the air for the words-- "he built this chatbot thing for Gerry, some kind of super-advanced AI. Gerry had just been diagnosed with Alzheimer's and I guess Michael was worried Gerry would forget him. He designed the chatbot to say he was in Australia to explain why he couldn't visit."

"That's awful," Mandy granted, "but I don't get what the problem is. I mean, surely he can show the AI Michael his own chatbot?"

"No, because you can't get the AI Michael on Skype. Michael just designed the program to look like Skype."

"But then--" Mandy went silent.

"Michael uploaded the entire AI to Gerry's computer before his death. Gerry didn't delete Skype. He deleted the AI Michael."

"So… that's it? He-he's gone?" Mandy's voice cracked. "He can't just be gone, surely he can't?"

The women stood staring at each other. They looked to the door of the study. They could still hear Gerry, gabbing away with his cybercopy.

"I can't go back in there," muttered Mandy. Her voice wavered as she tried to stem the misery rising in her throat.

Alice shook her head and paced the floor. She stopped and stared at Mandy with grim resignation. "We don't have a choice."

When they returned, Gerry was still happily chatting away.

"Hiya girls. Ya wanna ask my handsome twin any other questions? If not, we could get Michael on the phone?"

Neither woman spoke. Gerry clapped his hands and turned gaily to the monitor again: "I cannae wait for ya t'meet him, Gerry. He's gonna be impressed wi' you."

Alice clasped her hands to her mouth. Tears welled in the women's eyes as they watched the old man converse with his digital copy. The heat of the room seemed to swell, becoming insufferable. Mandy couldn't take it anymore. She jumped up, bolted to the door and collapsed against a wall in the hallway. Alice perched on the edge of her seat in a dumb daze, praying for the floor to open and swallow the contents of the room whole.

Oblivious, Gerry and his echo babbled away, the blue glow of the screen illuminating his euphoric face. "Just wait until y'meet him Gerry, just wait."

An astronaut peers through a portal in outer space.

What if people could just survive on sunlight like plants?

The admittedly outlandish question occurred to me after reading about how climate change will exacerbate drought, flooding, and worldwide food shortages. Many of these problems could be eliminated if human photosynthesis were possible. Had anyone ever tried it?

Extreme space travel exists at an ethically unique spot that makes human experimentation much more palatable.

I emailed Sidney Pierce, professor emeritus in the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of South Florida, who studies a type of sea slug, Elysia chlorotica, that eats photosynthetic algae, incorporating the algae's key cell structure into itself. It's still a mystery how exactly a slug can operate the part of the cell that converts sunlight into energy, which requires proteins made by genes to function, but the upshot is that the slugs can (and do) live on sunlight in-between feedings.

Pierce says he gets questions about human photosynthesis a couple of times a year, but it almost certainly wouldn't be worth it to try to develop the process in a human. "A high-metabolic rate, large animal like a human could probably not survive on photosynthesis," he wrote to me in an email. "The main reason is a lack of surface area. They would either have to grow leaves or pull a trailer covered with them."

In short: Plants have already exploited the best tricks for subsisting on photosynthesis, and unless we want to look and act like plants, we won't have much success ourselves. Not that it stopped Pierce from trying to develop human photosynthesis technology anyway: "I even tried to sell it to the Navy back in the day," he told me. "Imagine photosynthetic SEALS."

It turns out, however, that while no one is actively trying to create photosynthetic humans, scientists are considering the ways humans might need to change to adapt to future environments, either here on the rapidly changing Earth or on another planet. Rice University biologist Scott Solomon has written an entire book, Future Humans, in which he explores the environmental pressures that are likely to influence human evolution from this point forward. On Earth, Solomon says, infectious disease will remain a major driver of change. As for Mars, the big two are lower gravity and radiation, the latter of which bombards the Martian surface constantly because the planet has no magnetosphere.

Although he considers this example "pretty out there," Solomon says one possible solution to Mars' magnetic assault could leave humans not photosynthetic green, but orange, thanks to pigments called carotenoids that are responsible for the bright hues of pumpkins and carrots.

"Carotenoids protect against radiation," he says. "Usually only plants and microbes can produce carotenoids, but there's at least one kind of insect, a particular type of aphid, that somehow acquired the gene for making carotenoids from a fungus. We don't exactly know how that happened, but now they're orange... I view that as an example of, hey, maybe humans on Mars will evolve new kinds of pigmentation that will protect us from the radiation there."

We could wait for an orange human-producing genetic variation to occur naturally, or with new gene editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, we could just directly give astronauts genetic advantages such as carotenoid-producing skin. This may not be as far-off as it sounds: Extreme space travel exists at an ethically unique spot that makes human experimentation much more palatable. If an astronaut already plans to subject herself to the enormous experiment of traveling to, and maybe living out her days on, a dangerous and faraway planet, do we have any obligation to provide all the protection we can?

Probably the most vocal person trying to figure out what genetic protections might help astronauts is Cornell geneticist Chris Mason. His lab has outlined a 10-phase, 500-year plan for human survival, starting with the comparatively modest goal of establishing which human genes are not amenable to change and should be marked with a "Do not disturb" sign.

To be clear, Mason is not actually modifying human beings. Instead, his lab has studied genes in radiation-resistant bacteria, such as the Deinococcus genus. They've expressed proteins called DSUP from tardigrades, tiny water bears that can survive in space, in human cells. They've looked into p53, a gene that is overexpressed in elephants and seems to protect them from cancer. They also developed a protocol to work on the NASA twin study comparing astronauts Scott Kelly, who spent a year aboard the International Space Station, and his brother Mark, who did not, to find out what effects space tends to have on genes in the first place.

In a talk he gave in December, Mason reported that 8.7 percent of Scott Kelly's genes—mostly those associated with immune function, DNA repair, and bone formation—did not return to normal after the astronaut had been home for six months. "Some of these space genes, we could engineer them, activate them, have them be hyperactive when you go to space," he said in that same talk. "When we think about having the hubris to go to a faraway planet...it seems like an almost impossible idea….but I really like people and I want us to survive for a long time, and this is the first step on the stairwell to survive out of the solar system."

What is the most important ability we could give our future selves through science?

There are others performing studies to figure out what capabilities we might bestow on the future-proof superhuman, but none of them are quite as extreme as photosynthesis (although all of them are useful). At Harvard, geneticist George Church wants to engineer cells to be resistant to viruses, such as the common cold and HIV. At Columbia, synthetic biologist Harris Wang is addressing self-sufficient humans more directly—trying to spur kidney cells to produce amino acids that are normally only available from diet.

But perhaps Future Humans author Scott Solomon has the most radical idea. I asked him a version of the classic What would be your superhero power? question: What does he see as the most important ability we could give our future selves through science?

"The empathy gene," he said. "The ability to put yourself in someone else's shoes and see the world as they see it. I think it would solve a lot of our problems."

A model of a human kidney.

Science's dream of creating perfect custom organs on demand as soon as a patient needs one is still a long way off. But tiny versions are already serving as useful research tools and stepping stones toward full-fledged replacements.

Although organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, they are invaluable tools for research.

The Lowdown

Australian researchers have grown hundreds of mini human kidneys in the past few years. Known as organoids, they function much like their full-grown counterparts, minus a few features due to a lack of blood supply.

Cultivated in a petri dish, these kidneys are still a shadow of their human counterparts. They grow no larger than one-sixth of an inch in diameter; fully developed organs are up to five inches in length. They contain no more than a few dozen nephrons, the kidney's individual blood-filtering unit, whereas a fully-grown kidney has about 1 million nephrons. And the dish variety live for just a few weeks.

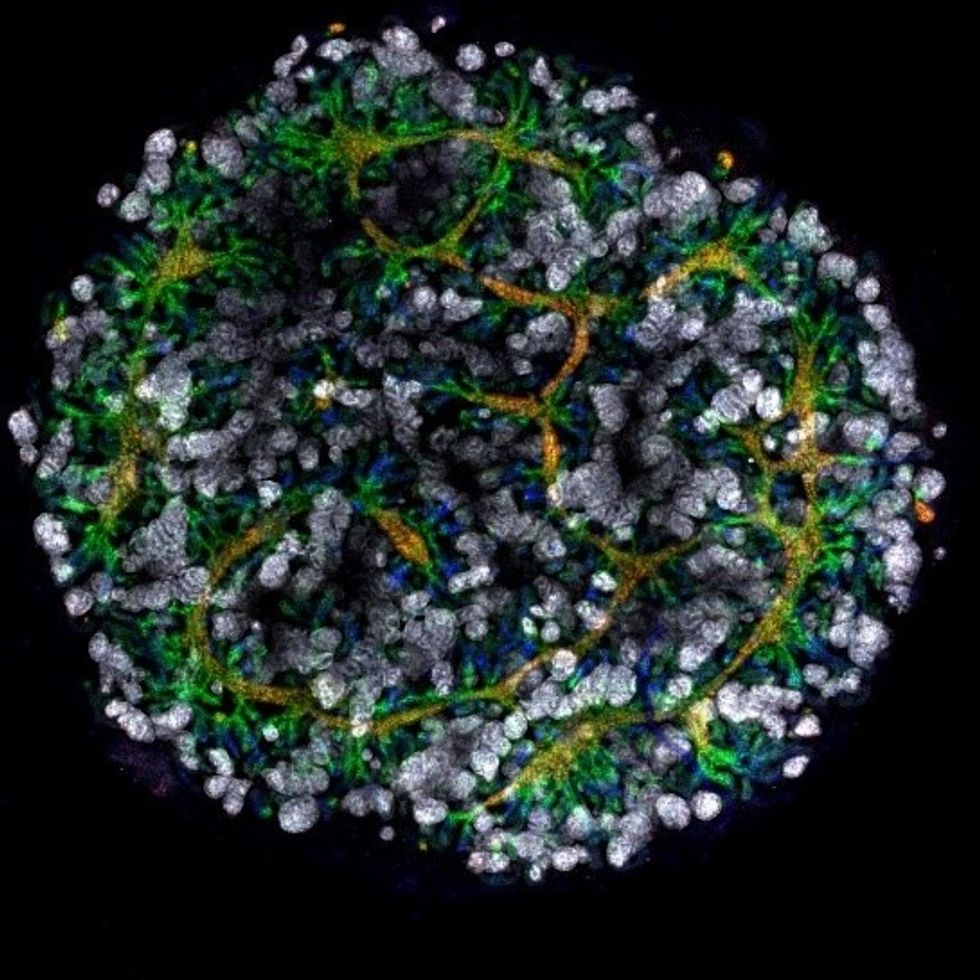

An organoid kidney created by the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo Credit: Shahnaz Khan.

But Melissa Little, head of the kidney research laboratory at the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, says these organoids are invaluable tools for research. Although renal failure is rare in children, more than half of those who suffer from such a disorder inherited it.

The mini kidneys enable scientists to better understand the progression of such disorders because they can be grown with a patient's specific genetic condition.

Mature stem cells can be extracted from a patient's blood sample and then reprogrammed to become like embryonic cells, able to turn into any type of cell in the body. It's akin to walking back the clock so that the cells regain unlimited potential for development. (The Japanese scientist who pioneered this technique was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2012.) These "induced pluripotent stem cells" can then be chemically coaxed to grow into mini kidneys that have the patient's genetic disorder.

"The (genetic) defects are quite clear in the organoids, and they can be monitored in the dish," Little says. To date, her research team has created organoids from 20 different stem cell lines.

Medication regimens can also be tested on the organoids, allowing specific tailoring for each patient. For now, such testing remains restricted to mice, but Little says it eventually will be done on human organoids so that the results can more accurately reflect how a given patient will respond to particular drugs.

Next Steps

Although these organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, Little says they may plug a huge gap in renal care by assisting in developing new treatments for chronic conditions. Currently, most patients with a serious kidney disorder see their options narrow to dialysis or organ transplantation. The former not only requires multiple sessions a week, but takes a huge toll on patient health.

Ten percent of older patients on dialysis die every year in the U.S. Aside from the physical trauma of organ transplantation, finding a suitable donor outside of a family member can be difficult.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells."

Meanwhile, the ongoing creation of organoids is supplying Little and her colleagues with enough information to create larger and more functional organs in the future. According to Little, researchers in the Netherlands, for example, have found that implanting organoids in mice leads to the creation of vascular growth, a potential pathway toward creating bigger and better kidneys.

And while Little acknowledges that creating a fully-formed custom organ is the ultimate goal, the mini organs are an important bridge step.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells, and I am just passionate to see it do some good."