Smartwatches can track COVID-19 symptoms, study finds

University of Michigan researchers found that new signals embedded in heart rate indicated when individuals were infected with COVID-19 and how ill they became.

If a COVID-19 infection develops, a wearable device may eventually be able to clue you in. A study at the University of Michigan found that a smartwatch can monitor how symptoms progress.

The study evaluated the effects of COVID-19 with various factors derived from heart-rate data. This method also could be employed to detect other diseases, such as influenza and the common cold, at home or when medical resources are limited, such as during a pandemic or in developing countries.

Tracking students and medical interns across the country, the University of Michigan researchers found that new signals embedded in heart rate indicated when individuals were infected with COVID-19 and how ill they became.

For instance, they discovered that individuals with COVID-19 experienced an increase in heart rate per step after the onset of their symptoms. Meanwhile, people who reported a cough as one of their COVID-19 symptoms had a much more elevated heart rate per step than those without a cough.

“We previously developed a variety of algorithms to analyze data from wearable devices. So, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it was only natural to apply some of these algorithms to see if we can get a better understanding of disease progression,” says Caleb Mayer, a doctoral student in mathematics at the University of Michigan and a co-first author of the study.

People may not internally sense COVID-19’s direct impact on the heart, but “heart rate is a vital sign that gives a picture of overall health," says Daniel Forger, a University of Michigan professor.

Millions of people are tracking their heart rate through wearable devices. This information is already generating a tremendous amount of data for researchers to analyze, says co-author Daniel Forger, professor of mathematics and research professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the University of Michigan.

“Heart rate is affected by many different physiological signals,” Forger explains. “For instance, if your lungs aren’t functioning properly, your heart may need to beat faster to meet metabolic demands. Your heart rate has a natural daily rhythm governed by internal biological clocks.” While people may not internally sense COVID-19’s direct impact on the heart, he adds that “heart rate is a vital sign that gives a picture of overall health.”

Among the total of 2,164 participants who enrolled in the student study, 72 undergraduate and graduate students contracted COVID-19, providing wearable data from 50 days before symptom onset to 14 days after. The researchers also analyzed this type of data for 43 medical interns from the Intern Health Study by the Michigan Neuroscience Institute and 29 individuals (who are not affiliated with the university) from the publicly available dataset.

Participants could wear the device on either wrist. They also documented their COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, shortness of breath, cough, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea, body aches, loss of taste, loss of smell, and sore throat.

Experts not involved in the study found the research to be productive. “This work is pioneering and reveals exciting new insights into the many important ways that we can derive clinically significant information about disease progression from consumer-grade wearable devices,” says Lisa A. Marsch, director of the Center for Technology and Behavioral Health and a professor in the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College. “Heart-rate data are among the highest-quality data that can be obtained via wearables.”

Beyond the heart, she adds, “Wearable devices are providing novel insights into individuals’ physiology and behavior in many health domains.” In particular, “this study beautifully illustrates how digital-health methodologies can markedly enhance our understanding of differences in individuals’ experience with disease and health.”

Previous studies had demonstrated that COVID-19 affects cardiovascular functions. Capitalizing on this knowledge, the University of Michigan endeavor took “a giant step forward,” says Gisele Oda, a researcher at the Institute of Biosciences at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil and an expert in chronobiology—the science of biological rhythms. She commends the researchers for developing a complex algorithm that “could extract useful information beyond the established knowledge that heart rate increases and becomes more irregular in COVID patients.”

Wearable devices open the possibility of obtaining large-scale, long, continuous, and real-time heart-rate data on people performing everyday activities or while sleeping. “Importantly, the conceptual basis of this algorithm put circadian rhythms at the center stage,” Oda says, referring to the physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. “What we knew before was often based on short-time heart rate measured at any time of day,” she adds, while noting that heart rate varies between day and night and also changes with activity.

However, without comparison to a control group of people having the common flu, it is difficult to determine if the heart-rate signals are unique to COVID-19 or also occur with other illnesses, says John Torous, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has researched wearable devices. In addition, he points to recent data showing that many wearables, which work by beaming light through the skin, may be less accurate in people with darker skin due to variations in light absorption.

While the results sound interesting, they lack the level of conclusive evidence that would be needed to transform how physicians care for patients. “But it is a good step in learning more about what these wearables can tell us,” says Torous, who is also director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard affiliate, in Boston. A follow-up step would entail replicating the results in a different pool of people to “help us realize the full value of this work.”

It is important to note that this research was conducted in university settings during the early phases of the pandemic, with remote learning in full swing amid strict isolation and quarantine mandates in effect. The findings demonstrate that physiological monitoring can be performed using consumer-grade wearable sensors, allowing research to continue without in-person contact, says Sung Won Choi, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan who is principal investigator of the student study.

“The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic interrupted a lot of activities that relied on face-to-face interactions, including clinical research,” Choi says. “Mobile technology proved to be tremendously beneficial during that time, because it allowed us to collect detailed physiological data from research participants remotely over an entire semester.” In fact, the researchers did not have any in-person contact with the students involved in the study. “Everything was done virtually," Choi explains. "Importantly, their willingness to participate in research and share data during this historical time, combined with the capacity of secure cloud storage and novel mathematical analytics, enabled our research teams to identify unique patterns in heart-rate data associated with COVID-19.”

7 Reasons Why We Should Not Need Boosters for COVID-19

A top infectious disease physician explains why immunity derived from natural infection and the vaccines should be long-lasting.

There are at least 7 reasons why immunity after vaccination or infection with COVID-19 should likely be long-lived. If durable, I do not think boosters will be necessary in the future, despite CEOs of pharmaceutical companies (who stand to profit from boosters) messaging that they may and readying such boosters. To explain these reasons, let's orient ourselves to the main components of the immune system.

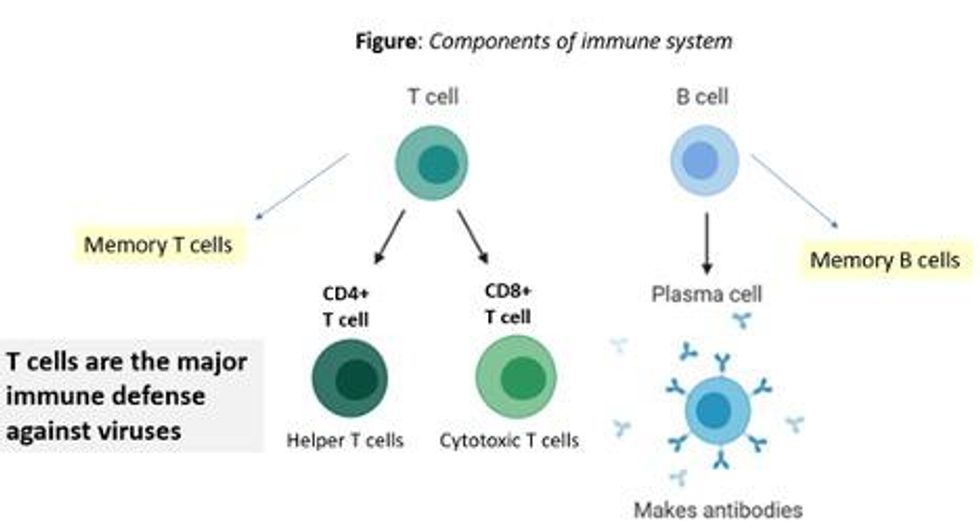

There are two major arms of the immune system: B cells (which produce antibodies) and T cells (which are formed specifically to attack and kill pathogens). T cells are divided into two types, CD4 cells ("helper" T cells) and CD8 cells ("cytotoxic" T cells).

Each arm, once stimulated by infection or vaccine, should hopefully make "memory" banks. So if the body sees the pathogen in the future, these defenses should come roaring back to attack the virus and protect you from getting sick. Plenty of research in COVID-19 indicates a likely long-lasting response to the vaccine or infection. Here are seven of the most compelling reasons:

REASON 1: Memory B Cells Are Produced By Vaccines and Natural Infection

In one study, 12 volunteers who had never had Covid-19--and were fully vaccinated with two Pfizer/BioNTech shots-- underwent biopsies of their lymph nodes. This is where memory B cells are stored in places called "germinal centers". The biopsies were performed three, four, six, and seven weeks after the first mRNA vaccine shot, and were stained to reveal that germinal center memory B cells in the lymph nodes increased in concentration over time.

Natural infection also generates memory B cells. Even after antibody levels wane over time, strong memory B cells were detected in the blood of individuals six and eight months after infection in different studies. Indeed, the half-lives of the memory B cells seen in the study examining patients 8 months after COVID-19 led the authors to conclude that "B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 was robust and is likely long-lasting." Reason #2 tells us that memory B cells can be active for a very long time indeed.

REASON #2: Memory B Cells Can Produce Neutralizing Antibodies If They See Infection Again Decades Later

Demonstrated production of memory B cells after vaccination or natural infection with COVID-19 is so important because memory B cells, once generated, can be activated to produce high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the pathogen even if encountered many years after the initial exposure. In one amazing study (published in 2008), researchers isolated memory B cells against the 1918 flu strain from the blood of 32 individuals aged 91-101 years. These people had been born on or before 1915 and had survived that pandemic.

Their memory B cells, when exposed to the 1918 flu strain in a test tube, generated high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the virus -- antibodies that then protected mice from lethal infection with this deadly strain. The ability of memory B cells to produce complex antibody responses against an infection nine decades after exposure speaks to their durability.

REASON #3: Vaccines or Natural Infection Trigger Strong Memory T Cell Immunity

All of the trials of the major COVID-19 vaccine candidates measured strong T cell immunity following vaccination, most often assessed by measuring SARS-CoV-2 specific T cells in the phase I/II safety and immunogenicity studies. There are a number of studies that demonstrate the production of strong T cell immunity to COVID-19 after natural infection as well, even when the infection was mild or asymptomatic.

The same study that showed us robust memory B cell production 8 months after natural infection also demonstrated strong and sustained memory T cell production. In fact, the half-lives of the memory T cells in this cohort were long (~125-225 days for CD8+ and ~94-153 days for CD4+ T cells), comparable to the 123-day half-life observed for memory CD8+ T cells after yellow fever immunization (a vaccine usually given once over a lifetime).

A recent study of individuals recovered from COVID-19 show that the initial T cells generated by natural infection mature and differentiate over time into memory T cells that will be "put in the bank" for sustained periods.

REASON #4: T Cell Immunity Following Vaccinations for Other Infections Is Long-Lasting

Last year, we were fortunate to be able to measure how T cell immunity is generated by COVID-19 vaccines, which was not possible in earlier eras when vaccine trials were done for other infections (such as measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, diphtheria). Antibodies are just the "tip of the iceberg" when assessing the response to vaccination, but were the only arm of the immune response that could be measured following vaccination in the past.

Measuring pathogen-specific T cell responses takes sophisticated technology. However, T cell responses, when assessed years after vaccination for other pathogens, has been shown to be long-lasting. For example, in one study of 56 volunteers who had undergone measles vaccination when they were much younger, strong CD8 and CD4 cell responses to vaccination could be detected up to 34 years later.

REASON #5: T Cell Immunity to Related Coronaviruses That Caused Severe Disease is Long-Lasting

SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus that causes severe disease, unlike coronaviruses that cause the common cold. Two other coronaviruses in the recent past caused severe disease, specifically Severely Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (SARS) in late 2002-2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2011.

A study performed in 2020 demonstrated that the blood of 23 recovered SARS patients possess long-lasting memory T cells that were still reactive to SARS 17 years after the outbreak in 2003. Many scientists expect that T cell immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will be equally durable to that of its cousin.

REASON #6: T Cell Responses from Vaccination and Natural Infection With the Ancestral Strain of COVID-19 Are Robust Against Variants

Even though antibody responses from vaccination may be slightly lower against various COVID-19 variants of concern that have emerged in recent months, T cell immunity after vaccination has been shown to be unperturbed by mutations in the spike protein (in the variants). For instance, T cell responses after mRNA vaccines maintained strong activity against different variants (including P.1 Brazil variant, B.1.1.7 UK variant, B.1.351 South Africa variant and the CA.20.C California variant) in a recent study.

Another study showed that the vaccines generated robust T cell immunity that was unfazed by different variants, including B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. The CD4 and CD8 responses generated after natural infection are equally robust, showing activity against multiple "epitopes" (little segments) of the spike protein of the virus. For instance, CD8 cells responds to 52 epitopes and CD4 cells respond to 57 epitopes across the spike protein, so that a few mutations in the variants cannot knock out such a robust and in-breadth T cell response. Indeed, a recent paper showed that mRNA vaccines were 97.4 percent effective against severe COVID-19 disease in Qatar, even when the majority of circulating virus there was from variants of concern (B.1.351 and B.1.1.7).

REASON #7: Coronaviruses Don't Mutate Quickly Like Influenza, Which Requires Annual Booster Shots

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses, like influenza and HIV (which is actually a retrovirus), but do not mutate as quickly as either one. The reason that coronaviruses don't mutate very rapidly is that their replicating mechanism (polymerase) has a strong proofreading mechanism: If the virus mutates, it usually goes back and self-corrects. Mutations can arise with high rates of replication when transmission is very frequent -- as has been seen in recent months with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants during surges. However, the COVID-19 virus will not be mutating like this when we tamp down transmission with mass vaccination.

In conclusion, I and many of my infectious disease colleagues expect the immunity from natural infection or vaccination to COVID-19 to be durable. Let's put discussion of boosters aside and work hard on global vaccine equity and distribution since the pandemic is not over until it is over for us all.

Professor Tim Caulfield stops by the "Making Sense of Science" podcast this month to discuss the infodemic around COVID-19 and how to deal with it.

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

Hear the 30-second trailer:

Listen to the whole episode:

.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.