Society Needs Regulations to Prevent Research Abuses

A tension exists between scientists/doctors and government regulators.

[Editor's Note: Our Big Moral Question this month is, "Do government regulations help or hurt the goal of responsible and timely scientific innovation?"]

Government regulations help more than hurt the goal of responsible and timely scientific innovation. Opponents might argue that without regulations, researchers would be free to do whatever they want. But without ethics and regulations, scientists have performed horrific experiments. In Nazi concentration camps, for instance, doctors forced prisoners to stay in the snow to see how long it took for these inmates to freeze to death. These researchers also removed prisoner's limbs in order to try to develop innovations to reconnect these body parts, but all the experiments failed.

Researchers in not only industry, but also academia have violated research participants' rights.

Due to these atrocities, after the war, the Nuremberg Tribunal established the first ethical guidelines for research, mandating that all study participants provide informed consent. Yet many researchers, including those in leading U.S. academic institutions and government agencies, failed to follow these dictates. The U.S. government, for instance, secretly infected Guatemalan men with syphilis in order to study the disease and experimented on soldiers, exposing them without consent to biological and chemical warfare agents. In the 1960s, researchers at New York's Willowbrook State School purposefully fed intellectually disabled children infected stool extracts with hepatitis to study the disease. In 1966, in the New England Journal of Medicine, Henry Beecher, a Harvard anesthesiologist, described 22 cases of unethical research published in the nation's leading medical journals, but were mostly conducted without informed consent, and at times harmed participants without offering them any benefit.

Despite heightened awareness and enhanced guidelines, abuses continued. Until a 1974 journalistic exposé, the U.S. government continued to fund the now-notorious Tuskegee syphilis study of infected poor African-American men in rural Alabama, refusing to offer these men penicillin when it became available as effective treatment for the disease.

In response, in 1974 Congress passed the National Research Act, establishing research ethics committees or Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), to guide scientists, allowing them to innovate while protecting study participants' rights. Routinely, IRBs now detect and prevent unethical studies from starting.

Still, even with these regulations, researchers have at times conducted unethical investigations. In 1999 at the Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, for example, a patient twice refused to participate in a study that would prolong his surgery. The researcher nonetheless proceeded to experiment on him anyway, using an electrical probe in the patient's heart to collect data.

Part of the problem and consequent need for regulations is that researchers have conflicts of interest and often do not recognize ethical challenges their research may pose.

Pharmaceutical company scandals, involving Avandia, and Neurontin and other drugs, raise added concerns. In marketing Vioxx, OxyContin, and tobacco, corporations have hidden findings that might undercut sales.

Regulations become increasingly critical as drug companies and the NIH conduct increasing amounts of research in the developing world. In 1996, Pfizer conducted a study of bacterial meningitis in Nigeria in which 11 children died. The families thus sued. Pfizer produced a Nigerian IRB approval letter, but the letter turned out to have been forged. No Nigerian IRB had ever approved the study. Fourteen years later, Wikileaks revealed that Pfizer had hired detectives to find evidence of corruption against the Nigerian Attorney General, to compel him to drop the lawsuit.

Researchers in not only industry, but also academia have violated research participants' rights. Arizona State University scientists wanted to investigate the genes of a Native American group, the Havasupai, who were concerned about their high rates of diabetes. The investigators also wanted to study the group's rates of schizophrenia, but feared that the tribe would oppose the study, given the stigma. Hence, these researchers decided to mislead the tribe, stating that the study was only about diabetes. The university's research ethics committee knew the scientists' plan to study schizophrenia, but approved the study, including the consent form, which did not mention any psychiatric diagnoses. The Havasupai gave blood samples, but later learned that the researchers published articles about the tribe's schizophrenia and alcoholism, and genetic origins in Asia (while the Havasupai believed they originated in the Grand Canyon, where they now lived, and which they thus argued they owned). A 2010 legal settlement required that the university return the blood samples to the tribe, which then destroyed them. Had the researchers instead worked with the tribe more respectfully, they could have advanced science in many ways.

Part of the problem and consequent need for regulations is that researchers have conflicts of interest and often do not recognize ethical challenges their research may pose.

Such violations threaten to lower public trust in science, particularly among vulnerable groups that have historically been systemically mistreated, diminishing public and government support for research and for the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation and Centers for Disease Control, all of which conduct large numbers of studies.

Research that has failed to follow ethics has in fact impeded innovation.

In popular culture, myths of immoral science and technology--from Frankenstein to Big Brother and Dr. Strangelove--loom.

Admittedly, regulations involve inherent tradeoffs. Following certain rules can take time and effort. Certain regulations may in fact limit research that might potentially advance knowledge, but be grossly unethical. For instance, if our society's sole goal was to have scientists innovate as much as possible, we might let them stick needles into healthy people's brains to remove cells in return for cash that many vulnerable poor people might find desirable. But these studies would clearly pose major ethical problems.

Research that has failed to follow ethics has in fact impeded innovation. In 1999, the death of a young man, Jesse Gelsinger, in a gene therapy experiment in which the investigator was subsequently found to have major conflicts of interest, delayed innovations in the field of gene therapy research for years.

Without regulations, companies might market products that prove dangerous, leading to massive lawsuits that could also ultimately stifle further innovation within an industry.

The key question is not whether regulations help or hurt science alone, but whether they help or hurt science that is both "responsible and innovative."

We don't want "over-regulation." Rather, the right amount of regulations is needed – neither too much nor too little. Hence, policy makers in this area have developed regulations in fair and transparent ways and have also been working to reduce the burden on researchers – for instance, by allowing single IRBs to review multi-site studies, rather than having multiple IRBs do so, which can create obstacles.

In sum, society requires a proper balance of regulations to ensure ethical research, avoid abuses, and ultimately aid us all by promoting responsible innovation.

[Ed. Note: Check out the opposite viewpoint here, and follow LeapsMag on social media to share your perspective.]

In this week's Friday Five, an old diabetes drug finds an exciting new purpose. Plus, how to make the cities of the future less toxic, making old mice younger with EVs, a new reason for mysterious stillbirths - and much more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here is the promising research covered in this week's Friday Five:

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

- How to make cities of the future less noisy

- An old diabetes drug could have a new purpose: treating an irregular heartbeat

- A new reason for mysterious stillbirths

- Making old mice younger with EVs

- No pain - or mucus - no gain

And an honorable mention this week: How treatments for depression can change the structure of the brain

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

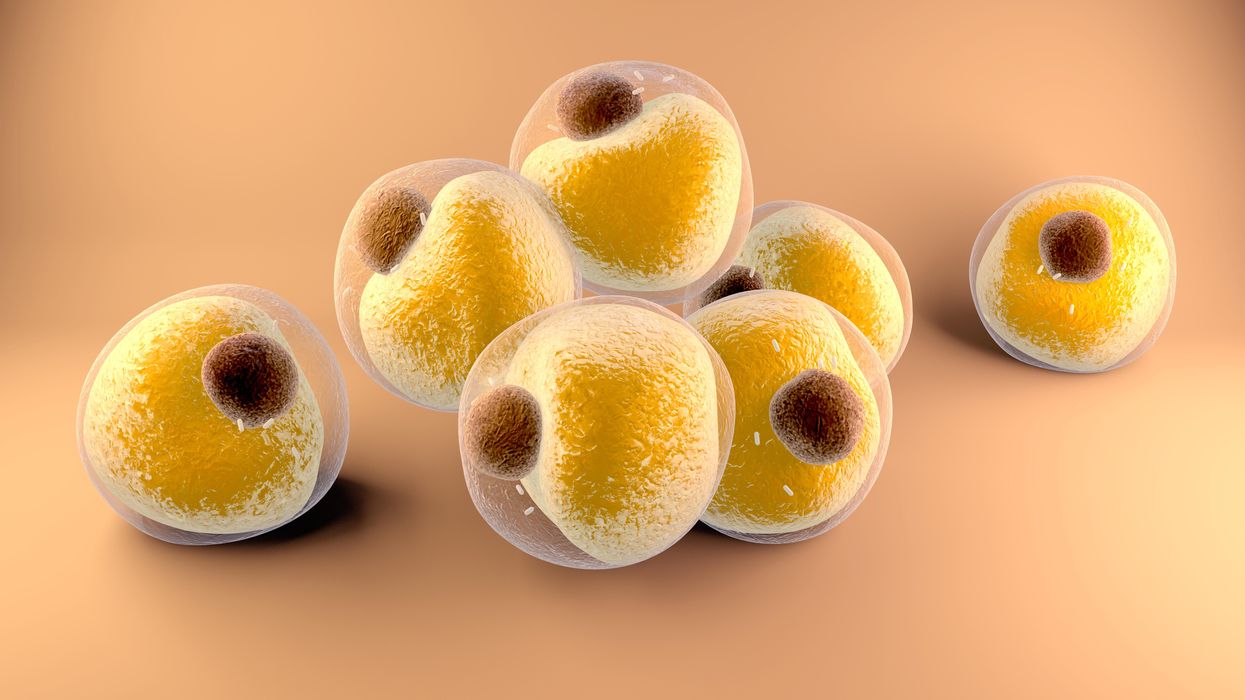

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.