New tools could catch disease outbreaks earlier - or predict them

A team at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies is utilizing drones and weather stations to collect data on how mosquito breeding patterns are changing in response to climate shifts.

Every year, the villages which lie in the so-called ‘Nipah belt’— which stretches along the western border between Bangladesh and India, brace themselves for the latest outbreak. For since 1998, when Nipah virus—a form of hemorrhagic fever most common in Bangladesh—first spilled over into humans, it has been a grim annual visitor to the people of this region.

With a 70 percent fatality rate, no vaccine, and no known treatments, Nipah virus has been dubbed in the Western world as ‘the worst disease no one has ever heard of.’ Currently, outbreaks tend to be relatively contained because it is not very transmissible. The virus circulates throughout Asia in fruit eating bats, and only tends to be passed on to people who consume contaminated date palm sap, a sweet drink which is harvested across Bangladesh.

But as SARS-CoV-2 has shown the world, this can quickly change.

“Nipah virus is among what virologists call ‘the Big 10,’ along with things like Lassa fever and Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever,” says Noam Ross, a disease ecologist at New York-based non-profit EcoHealth Alliance. “These are pretty dangerous viruses from a lethality perspective, which don’t currently have the capacity to spread into broader human populations. But that can evolve, and you could very well see a variant emerge that has human-human transmission capability.”

That’s not an overstatement. Surveys suggest that mammals harbour about 40,000 viruses, with roughly a quarter capable of infecting humans. The vast majority never get a chance to do so because we don’t encounter them, but climate change can alter that. Recent studies have found that as animals relocate to new habitats due to shifting environmental conditions, the coming decades will bring around 300,000 first encounters between species which normally don’t interact, especially in tropical Africa and southeast Asia. All these interactions will make it far more likely for hitherto unknown viruses to cross paths with humans.

That’s why for the last 16 years, EcoHealth Alliance has been conducting ongoing viral surveillance projects across Bangladesh. The goal is to understand why Nipah is so much more prevalent in the western part of the country, compared to the east, and keep a watchful eye out for new Nipah strains as well as other dangerous pathogens like Ebola.

"There are a lot of different infectious agents that are sensitive to climate change that don't have these sorts of software tools being developed for them," says Cat Lippi, medical geography researcher at the University of Florida.

Until very recently this kind of work has been hampered by the limitations of viral surveillance technology. The PREDICT project, a $200 million initiative funded by the United States Agency for International Development, which conducted surveillance across the Amazon Basin, Congo Basin and extensive parts of South and Southeast Asia, relied upon so-called nucleic acid assays which enabled scientists to search for the genetic material of viruses in animal samples.

However, the project came under criticism for being highly inefficient. “That approach requires a big sampling effort, because of the rarity of individual infections,” says Ross. “Any particular animal may be infected for a couple of weeks, maybe once or twice in its lifetime. So if you sample thousands and thousands of animals, you'll eventually get one that has an Ebola virus infection right now.”

Ross explains that there is now far more interest in serological sampling—the scientific term for the process of drawing blood for antibody testing. By searching for the presence of antibodies in the blood of humans and animals, scientists have a greater chance of detecting viruses which started circulating recently.

Despite the controversy surrounding EcoHealth Alliance’s involvement in so-called gain of function research—experiments that study whether viruses might mutate into deadlier strains—the organization’s separate efforts to stay one step ahead of pathogen evolution are key to stopping the next pandemic.

“Having really cheap and fast surveillance is really important,” says Ross. “Particularly in a place where there's persistent, low level, moderate infections that potentially have the ability to develop into more epidemic or pandemic situations. It means there’s a pathway that something more dangerous can come through."

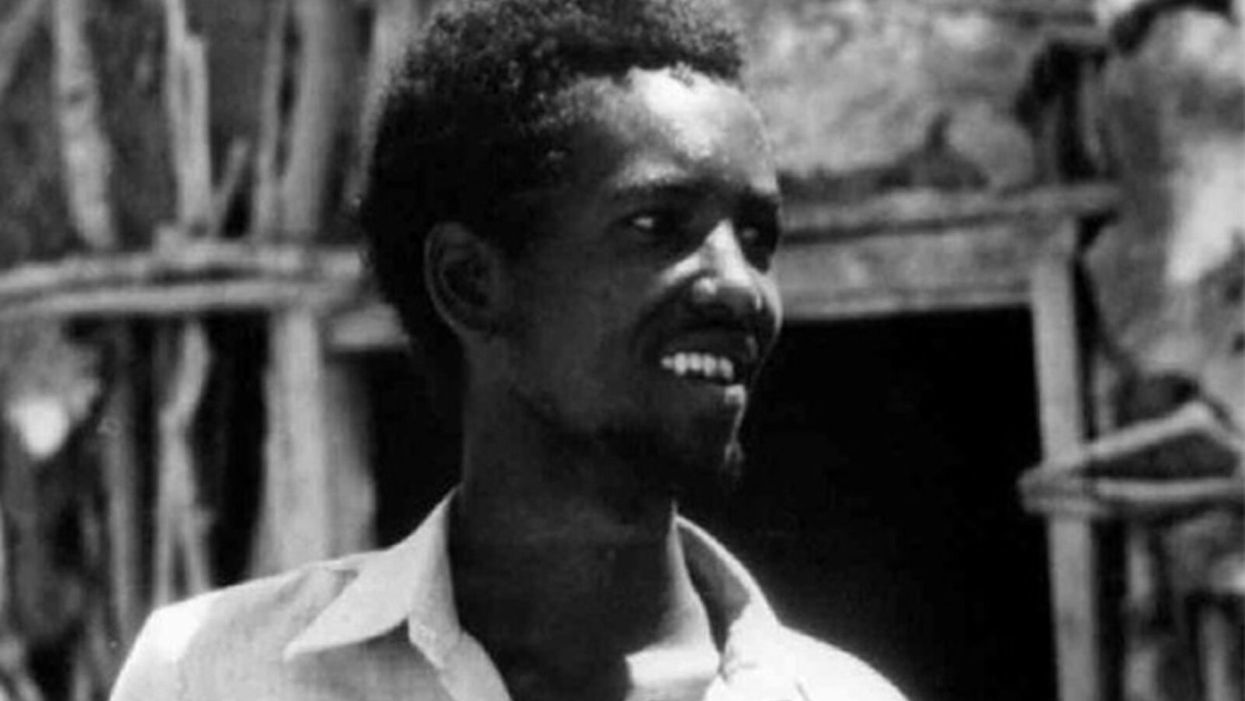

Scientists are searching for the presence of antibodies in the blood of humans and animals in hopes to detect viruses that recently started circulating.

EcoHealth Alliance

In Bangladesh, EcoHealth Alliance is attempting to do this using a newer serological technology known as a multiplex Luminex assay, which tests samples against a panel of known antibodies against many different viruses. It collects what Ross describes as a ‘footprint of information,’ which allows scientists to tell whether the sample contains the presence of a known pathogen or something completely different and needs to be investigated further.

By using this technology to sample human and animal populations across the country, they hope to gain an idea of whether there are any novel Nipah virus variants or strains from the same family, as well as other deadly viral families like Ebola.

This is just one of several novel tools being used for viral discovery in surveillance projects around the globe. Multiple research groups are taking PREDICT’s approach of looking for novel viruses in animals in various hotspots. They collect environmental DNA—mucus, faeces or shed skin left behind in soil, sediment or water—which can then be genetically sequenced.

Five years ago, this would have been a painstaking work requiring bringing collected samples back to labs. Today, thanks to the vast amounts of money spent on new technologies during COVID-19, researchers now have portable sequencing tools they can take out into the field.

Christopher Jerde, a researcher at the UC Santa Barbara Marine Science Institute, points to the Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencer as one example. “I tried one of the early versions of it four years ago, and it was miserable,” he says. “But they’ve really improved, and what we’re going to be able to do in the next five to ten years will be amazing. Instead of having to carefully transport samples back to the lab, we're going to have cigar box-shaped sequencers that we take into the field, plug into a laptop, and do the whole sequencing of an organism.”

In the past, viral surveillance has had to be very targeted and focused on known families of viruses, potentially missing new, previously unknown zoonotic pathogens. Jerde says that the rise of portable sequencers will lead to what he describes as “true surveillance.”

“Before, this was just too complex,” he says. “It had to be very focused, for example, looking for SARS-type viruses. Now we’re able to say, ‘Tell us all the viruses that are here?’ And this will give us true surveillance – we’ll be able to see the diversity of all the pathogens which are in these spots and have an understanding of which ones are coming into the population and causing damage.”

But being able to discover more viruses also comes with certain challenges. Some scientists fear that the speed of viral discovery will soon outpace the human capacity to analyze them all and assess the threat that they pose to us.

“I think we're already there,” says Jason Ladner, assistant professor at Northern Arizona University’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute. “If you look at all the papers on the expanding RNA virus sphere, there are all of these deposited partial or complete viral sequences in groups that we just don't know anything really about yet.” Bats, for example, carry a myriad of viruses, whose ability to infect human cells we understand very poorly.

Cultivating these viruses under laboratory conditions and testing them on organoids— miniature, simplified versions of organs created from stem cells—can help with these assessments, but it is a slow and painstaking work. One hope is that in the future, machine learning could help automate this process. The new SpillOver Viral Risk Ranking platform aims to assess the risk level of a given virus based on 31 different metrics, while other computer models have tried to do the same based on the similarity of a virus’s genomic sequence to known zoonotic threats.

However, Ladner says that these types of comparisons are still overly simplistic. For one thing, scientists are still only aware of a few hundred zoonotic viruses, which is a very limited data sample for accurately assessing a novel pathogen. Instead, he says that there is a need for virologists to develop models which can determine viral compatibility with human cells, based on genomic data.

“One thing which is really useful, but can be challenging to do, is understand the cell surface receptors that a given virus might use,” he says. “Understanding whether a virus is likely to be able to use proteins on the surface of human cells to gain entry can be very informative.”

As the Earth’s climate heats up, scientists also need to better model the so-called vector borne diseases such as dengue, Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever. Transmitted by the Aedes mosquito residing in humid climates, these blights currently disproportionally affect people in low-income nations. But predictions suggest that as the planet warms and the pests find new homes, an estimated one billion people who currently don’t encounter them might be threatened by their bites by 2080. “When it comes to mosquito-borne diseases we have to worry about shifts in suitable habitat,” says Cat Lippi, a medical geography researcher at the University of Florida. “As climate patterns change on these big scales, we expect to see shifts in where people will be at risk for contracting these diseases.”

Public health practitioners and government decision-makers need tools to make climate-informed decisions about the evolving threat of different infectious diseases. Some projects are already underway. An ongoing collaboration between the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies and researchers in Brazil and Peru is utilizing drones and weather stations to collect data on how mosquitoes change their breeding patterns in response to climate shifts. This information will then be fed into computer algorithms to predict the impact of mosquito-borne illnesses on different regions.

The team at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies is using drones and weather stations to collect data on how mosquito breeding patterns change due to climate shifts.

Gabriel Carrasco

Lippi says that similar models are urgently needed to predict how changing climate patterns affect respiratory, foodborne, waterborne and soilborne illnesses. The UK-based Wellcome Trust has allocated significant assets to fund such projects, which should allow scientists to monitor the impact of climate on a much broader range of infections. “There are a lot of different infectious agents that are sensitive to climate change that don't have these sorts of software tools being developed for them,” she says.

COVID-19’s havoc boosted funding for infectious disease research, but as its threats begin to fade from policymakers’ focus, the money may dry up. Meanwhile, scientists warn that another major infectious disease outbreak is inevitable, potentially within the next decade, so combing the planet for pathogens is vital. “Surveillance is ultimately a really boring thing that a lot of people don't want to put money into, until we have a wide scale pandemic,” Jerde says, but that vigilance is key to thwarting the next deadly horror. “It takes a lot of patience and perseverance to keep looking.”

This article originally appeared in One Health/One Planet, a single-issue magazine that explores how climate change and other environmental shifts are increasing vulnerabilities to infectious diseases by land and by sea. The magazine probes how scientists are making progress with leaders in other fields toward solutions that embrace diverse perspectives and the interconnectedness of all lifeforms and the planet.

How Smallpox Was Wiped Off the Planet By a Vaccine and Global Cooperation

The world's last recorded case of endemic smallpox was in Ali Maow Maalin, of Merka, Somalia, in October 1977. He made a full recovery.

For 3000 years, civilizations all over the world were brutalized by smallpox, an infectious and deadly virus characterized by fever and a rash of painful, oozing sores.

Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success.

Smallpox was merciless, killing one third of people it infected and leaving many survivors permanently pockmarked and blind. Although smallpox was more common during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was still a leading cause of death even up until the early 1950s, killing an estimated 50 million people annually.

A Primitive Cure

Sometime during the 10th century, Chinese physicians figured out that exposing people to a tiny bit of smallpox would sometimes result in a milder infection and immunity to the disease afterward (if the person survived). Desperate for a cure, people would huff powders made of smallpox scabs or insert smallpox pus into their skin, all in the hopes of getting immunity without having to get too sick. However, this method – called inoculation – didn't always work. People could still catch the full-blown disease, spread it to others, or even catch another infectious disease like syphilis in the process.

A Breakthrough Treatment

For centuries, inoculation – however imperfect – was the only protection the world had against smallpox. But in the late 18th century, an English physician named Edward Jenner created a more effective method. Jenner discovered that inoculating a person with cowpox – a much milder relative of the smallpox virus – would make that person immune to smallpox as well, but this time without the possibility of actually catching or transmitting smallpox. His breakthrough became the world's first vaccine against a contagious disease. Other researchers, like Louis Pasteur, would use these same principles to make vaccines for global killers like anthrax and rabies. Vaccination was considered a miracle, conferring all of the rewards of having gotten sick (immunity) without the risk of death or blindness.

Scaling the Cure

As vaccination became more widespread, the number of global smallpox deaths began to drop, particularly in Europe and the United States. But even as late as 1967, smallpox was still killing anywhere from 10 to 15 million people in poorer parts of the globe. The World Health Assembly (a decision-making body of the World Health Organization) decided that year to launch the first coordinated effort to eradicate smallpox from the planet completely, aiming for 80 percent vaccine coverage in every country in which the disease was endemic – a total of 33 countries.

But officials knew that eradicating smallpox would be easier said than done. Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success. The vaccination initiative in Bangladesh proved the most challenging, due to its population density and the prevalence of the disease, writes journalist Laurie Garrett in her book, The Coming Plague.

In one instance, French physician Daniel Tarantola on assignment in Bangladesh confronted a murderous gang that was thought to be spreading smallpox throughout the countryside during their crime sprees. Without police protection, Tarantola confronted the gang and "faced down guns" in order to immunize them, protecting the villagers from repeated outbreaks.

Because not enough vaccines existed to vaccinate everyone in a given country, doctors utilized a strategy called "ring vaccination," which meant locating individual outbreaks and vaccinating all known and possible contacts to stop an outbreak at its source. Fewer than 50 percent of the population in Nigeria received a vaccine, for example, but thanks to ring vaccination, it was eradicated in that country nonetheless. Doctors worked tirelessly for the next eleven years to immunize as many people as possible.

The World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

A Resounding Success

In November 1975, officials discovered a case of variola major — the more virulent strain of the smallpox virus — in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl named Rahima Banu. Banu was forcibly quarantined in her family's home with armed guards until the risk of transmission had passed, while officials went door-to-door vaccinating everyone within a five-mile radius. Two years later, the last case of variola major in human history was reported in Somalia. When no new community-acquired cases appeared after that, the World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

Because of smallpox, we now know it's possible to completely eliminate a disease. But is it likely to happen again with other diseases, like COVID-19? Some scientists aren't so sure. As dangerous as smallpox was, it had a few characteristics that made eradication possibly easier than for other diseases. Smallpox, for instance, has no animal reservoir, meaning that it could not circulate in animals and resurge in a human population at a later date. Additionally, a person who had smallpox once was guaranteed immunity from the disease thereafter — which is not the case for COVID-19.

In The Coming Plague, Japanese physician Isao Arita, who led the WHO's Smallpox Eradication Unit, admitted to routinely defying orders from the WHO, mobilizing to parts of the world without official approval and sometimes even vaccinating people against their will. "If we hadn't broken every single WHO rule many times over, we would have never defeated smallpox," Arita said. "Never."

Still, thanks to the life-saving technology of vaccines – and the tireless efforts of doctors and scientists across the globe – a once-lethal disease is now a thing of the past.

Over 1 Million Seeds Are Buried Near the North Pole to Back Up the World’s Crops

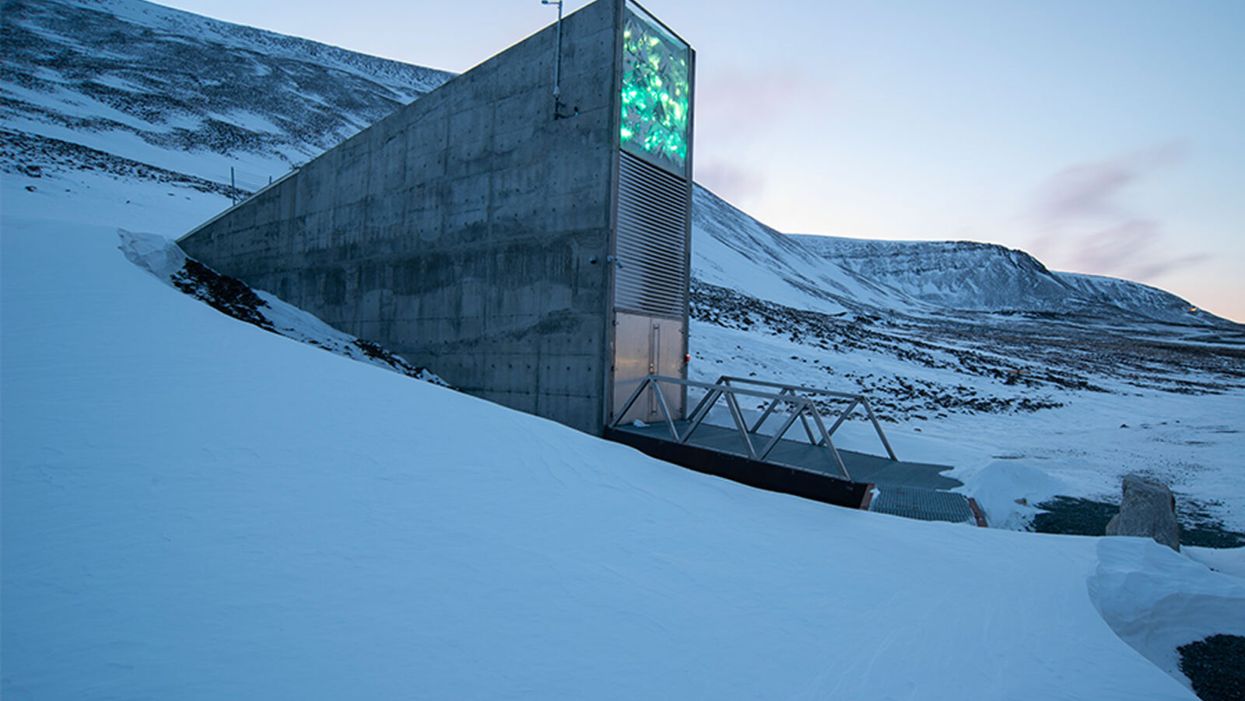

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault preserves more than one million of the world's seeds deep inside Platäfjellet Mountain.

The impressive structure protrudes from the side of a snowy mountain on the Svalbard Archipelago, a cluster of islands about halfway between Norway and the North Pole.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost. We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

Art installations on the building's rooftop and front façade glimmer like diamonds in the polar night, but it is what lies buried deep inside the frozen rock, 475 feet from the building's entrance, that is most precious. Here, in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, are backup copies of more than a million of the world's agricultural seeds.

Inside the vault, seed boxes from many gene banks and many countries. "The seeds don't know national boundaries," says Kent Nnadozie, the UN's Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

(Photo credit: Svalbard Global Seed Vault/Riccardo Gangale)

The Svalbard vault -- which has been called the Doomsday Vault, or a Noah's Ark for seeds -- preserves the genetic materials of more than 6000 crop species and their wild relatives, including many of the varieties within those species. Svalbard's collection represents all the traits that will enable the plants that feed the world to adapt – with the help of farmers and plant breeders – to rapidly changing climactic conditions, including rising temperatures, more intense drought, and increasing soil salinity. "We save these seeds because we want to ensure food security for future generations," says Grethe Helene Evjen, Senior Advisor at the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food .

A recent study in the journal Nature predicted that global warming could cause catastrophic losses of biodiversity in regions across the globe throughout this century. Yet global warming also threatens the permafrost that surrounds the seed vault, the very thing that was once considered a failsafe means of keeping these seeds frozen and safeguarding the diversity of our crops. In fact, record temperatures in Svalbard a few years ago – and a significant breach of water into the access tunnel to the vault -- prompted the Norwegian government to invest $20 million euros on improvements at the facility to further secure the genetic resources locked inside. The hope: that technology can work in concert with nature's freezer to keep the world's seeds viable.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost," says Hege Njaa Aschim, a spokesperson for Statsbygg, the government agency that recently completed the upgrades at the seed vault. "We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

The Apex of the Global Conservation System

More than 1700 genebanks around the globe preserve the diverse seed varieties from their regions. They range from small community seed banks in developing countries, where small farmers save and trade their seeds with growers in nearby villages, to specialized university collections, to national and international genetic resource repositories. But many of these facilities are vulnerable to war, natural disasters, or even lack of funding.

"If anything should happen to the resources in a regular genebank, Svalbard is the backup – it's essentially the apex of the global conservation system," says Kent Nnadozie, Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture at the United Nations, who likens the Global Vault to the Central Reserve Bank. "You have regular banks that do active trading, but the Central Bank is the final reserve where the banks store their gold deposits."

Similarly, farmers deposit their seeds in regional genebanks, and also look to these banks for new varieties to help their crops adapt to, say, increasing temperatures, or resist intrusive pests. Regional banks, in turn, store duplicates from their collections at Svalbard. These seeds remain the sovereign property of the country or institution depositing them; only they can "make a withdrawal."

The Global Vault has already proven invaluable: The International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), formerly located outside of Aleppo, Syria, held more than 140,000 seed samples, including plants that were extinct in their natural habitats, before the Syrian Crisis in 2012. Fortunately, they had managed to back up most of their seed samples at Svalbard before they were forced to relocate to Lebanon and Morocco. In 2017, ICARDA became the first – and only – organization to withdraw their stored seeds. They have now regenerated almost all of the samples at their new locations and recently redeposited new seeds for safekeeping at Svalbard.

Rapid Global Warming Threatens Permafrost

The Global Vault, a joint venture between the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) that started operating in 2008, was sited in Svalbard in part because of its remote yet accessible location: Svalbard is the northernmost inhabited spot on Earth with an airport. But experts also thought it a failsafe choice for long-term seed storage because its permafrost would offer natural freezing – even if cooling systems were to fail. No one imagined that the permafrost could fail.

"We've had record temperatures in the region recently, and there are a lot of signs that global warming is happening faster at the extreme latitudes," says Geoff Hawtin, a world-renowned authority in plant conservation, who is the founding director of -- and now advisor to -- the Crop Trust. "Svalbard is still arguably one of the safest places for the seeds from a temperature point of view, but it's actually not going to be as cold as we thought 20 years ago."

A recent report by the Norwegian Centre for Climate Services predicted that Svalbard could become 50 degrees Fahrenheit warmer by the year 2100. And data from the Norwegian government's environmental monitoring system in Svalbard shows that the permafrost is already thawing: The "active layer," that is, the layer of surface soil that seasonally thaws, has become 25-30 cm thicker since 1998.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization.

Though the permafrost surrounding the seed vault chambers, which are situated well below the active layer, is still intact, the permafrost around the access tunnel never re-established as expected after construction of the Global Vault twelve years ago. As a result, when Svalbard saw record high temperatures and unprecedented rainfall in 2016, about 164 feet of rainwater and snowmelt leaked into the tunnel, turning it into a skating rink and spurring authorities to take what they called a "better safe than sorry approach." They invested in major upgrades to the facility. "The seeds in the vault were never threatened," says Aschim, "but technology has become more important at Svalbard."

Technology Gives Nature a Boost

For now, the permafrost deep inside the mountain still keeps the temperature in the vault down to about -25°F. The cooling systems then give nature a mechanical boost to keep the seed vault chilled even further, to about -64°F, the optimal temperature for conserving seeds. In addition to upgrading to a more effective and sustainable cooling system that runs on CO2, the Norwegian government added backup generators, removed heat-generating electrical equipment from inside the facility to an outside building, installed a thick, watertight door to the vault, and replaced the corrugated steel access tunnel with a cement tunnel that uses the same waterproofing technology as the North Sea oil platforms.

To re-establish the permafrost around the tunnel, they layered cooling pipes with frozen soil around the concrete tunnel, covered the frozen soil with a cooling mat, and topped the cooling mat with the original permafrost soil. They also added drainage ditches on the mountainside to divert meltwater away from the tunnel as the climate gets warmer and wetter.

New Deposits to the Global Vault

The day before COVID-19 arrived in Norway, on February 25th, Prime Minister Erna Solberg hosted the biggest seed-depositing event in the vault's history in honor of the new and improved vault. As snow fell on Svalbard, depositors from almost every continent traveled the windy road from Longyearbyen up Platåfjellet Mountain and braved frigid -8°F weather to celebrate the massive technical upgrades to the facility – and to hand over their seeds.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization, and Israel's University of Haifa, whose deposit included multiple genotypes of wild emmer wheat, an ancient relative of the modern domesticated crop. The storage boxes carried ceremoniously over the threshold that day contained more than 65,000 new seed samples, bringing the total to more than a million, and almost filling the first of three seed chambers in the vault. (The Global Vault can store up to 4.5 million seed samples.)

"Svalbard's samples contain all the possibilities, all the options for the future of our agricultural crops – it's how crops are going to adapt," says Cary Fowler, former executive director of the Crop Trust, who was instrumental in establishing the Global Vault. "If our crops don't adapt to climate change, then neither will we." Dr. Fowler says he is confident that with the recent improvements in the vault, the seeds are going to remain viable for a very long time.

"It's sometimes tempting to get distracted by the romanticism of a seed vault inside a mountain near the North Pole – it's a little bit James Bondish," muses Dr. Fowler. "But the reality is we've essentially put an end to the extinction of more than a million samples of biodiversity forever."