Is Carbon Dioxide the New Black? Yes, If These Fabric-Designing Scientists Have Their Way

The entrepreneurs Tawfiq Nasr Allah (left, standing) and Benoit Illy (right, sitting down) at Fairbrics' lab in Clichy, France.

Each year the world releases around 33 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. What if we could use this waste carbon dioxide to make shirts, dresses and hats? It sounds unbelievable. But two innovators are trying to tackle climate change in this truly unique way.

Chemist Tawfiq Nasr Allah set up Fairbrics with material scientist Benoît Illy in 2019. They're using waste carbon dioxide from industrial fumes as a raw material to create polyester, identical to the everyday polyester we use now. They want to take a new and very different approach to make the fashion industry more sustainable.

The Dark Side of Fast Fashion

The fashion industry is responsible for around 4% of global emissions. In a 2015 report, the MIT Materials Systems Laboratory predicted that the global impact of polyester fabric will grow from around 880 billion kg of CO2 in 2015 to 1.5 trillion kg of CO2 by 2030.

Professor Greg Peters, an expert in environmental science and sustainability, highlights the wide-ranging difficulties caused by the production of polyester. "Because it is made from petrochemical crude oil there is no real limit on how much polyester can be produced...You have to consider the ecological damage (oil spills, fracking etc.) caused by the oil and gas industry."

Many big-name brands have pledged to become carbon neutral by 2050. But nothing has really changed in the way polyester is produced.

Some companies are recycling plastic bottles into polyester. The plastic is melted into ultra-fine strands and then spun to create polyester. However, only a limited number of bottles are available. New materials must be added because of the amount of plastic degradation that takes place. Ultimately, recycling accounts for only a small percentage of the total amount of polyester produced.

Nasr Allah and Illy hope they can offer the solution the fashion industry is looking for. They are not just reducing the carbon emissions that are conventionally produced by making polyester. Their process actually goes much further. It's carbon negative and works by using up emissions from other industries.

"In a sense we imitate what nature does so well: plants capture CO2 and turn it into natural fibers using sunlight, we capture CO2 and turn it into synthetic fibers using electricity."

Experts in the field see a lot of promise. Dr Phil de Luna is an expert in carbon valorization -- the process of converting carbon dioxide into high-value chemicals. He leads a $57-million research program developing the technology to decarbonize Canada.

"I think the approach is great," he says. "Being able to take CO2 and then convert it into polymers or polyester is an excellent way to think about utilizing waste emissions and replacing fossil fuel-based materials. That is overall a net negative as compared to making polyester from fossil fuels."

From Harmful Waste to Useful Raw Material

It all started with Nasr Allah's academic research, primarily at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA). He spent almost 5 years investigating CO2 valorization. In essence, this involves breaking the bonds between the carbon and oxygen atoms in CO2 to create bonds with other elements.

Recycling carbon dioxide in this way requires extremely high temperatures and pressures. Catalysts are needed to break the strong bonds between the atoms. However, these are toxic, volatile and quickly lose their effectiveness over time. So, directly converting carbon dioxide into the raw material for making polyester fibers is very difficult.

Nasr Allah developed a process involving multiple simpler stages. His innovative approach involves converting carbon dioxide to intermediate chemicals. These chemicals can then be transformed into the raw material which is used in the production of polyester. After many experiments, Nasr Allah developed new processes and new catalysts that worked more effectively.

"We use a catalyst to transform CO2 into the chemicals that are used for polyester manufacturing," Illy says. "In a sense we imitate what nature does so well: plants capture CO2 and turn it into natural fibers using sunlight, we capture CO2 and turn it into synthetic fibers using electricity."

The Challenges Ahead

Nasr Allah met material scientist Illy through Entrepreneur First, a programme which pairs individuals looking to form technical start-ups. Together they set up Fairbrics and worked on converting Nasr Allah's lab findings into commercial applications and industrial success.

"The main challenge we faced was to scale up the process," Illy reveals. "[It had to be] consistent and safe to be carried out by a trained technician, not a specialist PhD as was the case in the beginning."

They recruited a team of scientists to help them develop a more effective and robust manufacturing process. Together, the team gained a more detailed theoretical understanding about what was happening at each stage of the chemical reactions. Eventually, they were able to fine tune the process and produce consistent batches of polyester.

They're making significant progress. They've produced their first samples and signed their first commercial contract to make polyester, which will then be both fabricated into clothes and sold by partner companies.

Currently, one of the largest challenges is financial. "We need to raise a fair amount to buy the equipment we need to produce at a large scale," Illy explains.

How to Power the Process?

At the moment, their main scientific focus is getting the process working reliably so they can begin commercialization. In order to remain sustainable and economically viable once they start producing polyester on a large scale, they need to consider the amount of energy they use for carbon valorization and the emissions they produce.

The more they optimize the way their catalyst works, the easier it will be to transform the CO2. The whole process can then become more cost effective and energy efficient.

De Luna explains: "My concern is...whether their process will be economical at scale. The problem is the energy cost to take carbon dioxide and transform it into these other products and that's where the science and innovation has to happen. [Whether they can scale up economically] depends on the performance of their catalyst."

They don't just need to think about the amount of energy they use to produce polyester; they also have to consider where this energy comes from.

"They need access to cheap renewable energy," De Luna says, "...so they're not using or emitting CO2 to do the conversion." If the energy they use to transform CO2 into polyester actually ends up producing more CO2, this will end up cancelling out their positive environmental impact.

Based in France, they're well located to address this issue. France has a clean electricity system, with only about 10% of their electric power coming from fossil fuels due to their reliance on nuclear energy and renewables.

Where Do They Get the Carbon Dioxide?

As they scale up, they also need to be able to access a source of CO2. They intend to obtain this from the steel industry, the cement industry, and hydrogen production.

The technology to purify and capture waste carbon dioxide from these industries is available on a large scale. However, there are only around 20 commercial operations in the world. The high cost of carbon capture means that development continues to be slow. There are a growing number of startups capturing carbon dioxide straight from the air, but this is even more costly.

One major problem is that storing captured carbon dioxide is expensive. "There are somewhat limited options for permanently storing captured CO2, so innovations like this are important,'' says T. Reed Miller, a researcher at the Yale University Center for Industrial Ecology.

Illy says: "The challenge is now to decrease the cost [of carbon capture]. By using CO2 as a raw material, we can try to increase the number of industries that capture CO2. Our goal is to turn CO2 from a waste into a valuable product."

Beyond Fashion

For Nasr Allah and Illy, fashion is just the beginning. There are many markets they can potentially break into. Next, they hope to use the polyester they've created in the packaging industry. Today, a lot of polyester is consumed to make bottles and jars. Illy believes that eventually they can produce many different chemicals from CO2. These chemicals could then be used to make paints, adhesives, and even plastics.

The Fairbrics scientists are providing a vital alternative to fossil fuels and showcasing the real potential of carbon dioxide to become a worthy resource instead of a harmful polluter.

Illy believes they can make a real difference through innovation: "We can have a significant impact in reducing climate change."

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

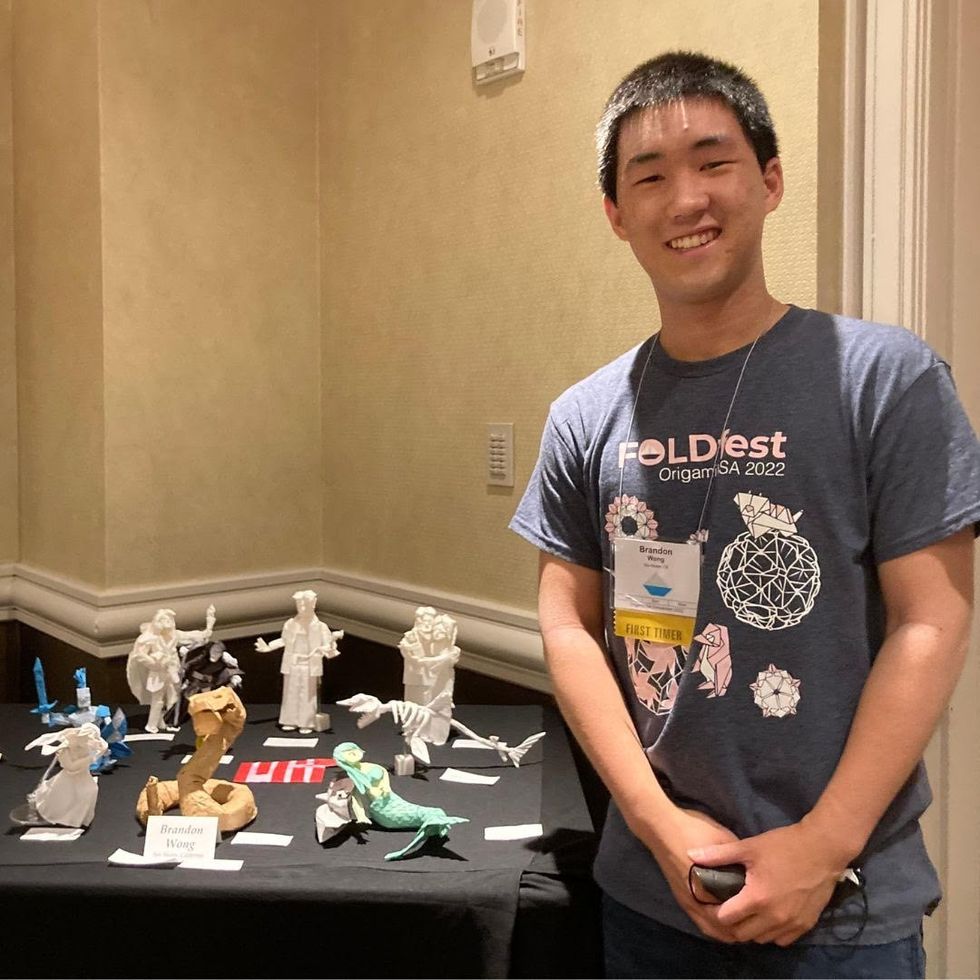

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”