“Synthetic Embryos”: The Wrong Term For Important New Research

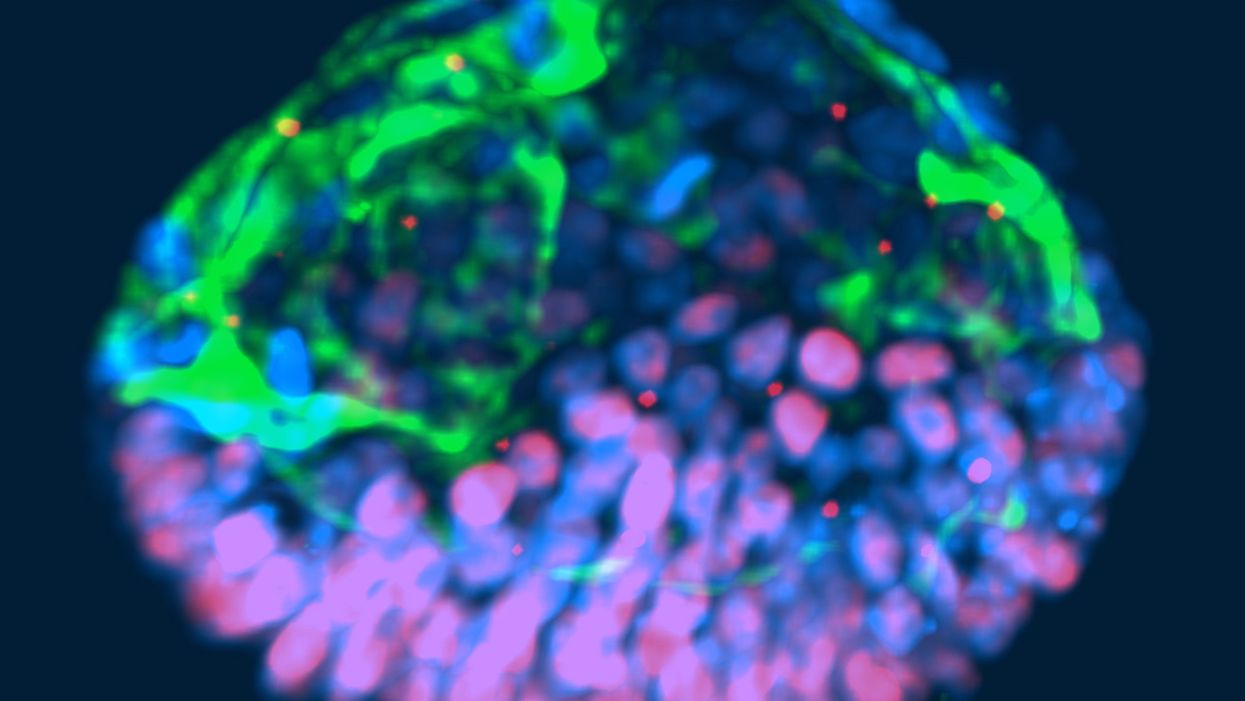

This fluorescent image shows a representative post-implantation amniotic sac embroid.

As a subject of research, an unusual degree of consensus appears to exist among scientists, politicians and the public about human embryos being deserving of special considerations. But what those special considerations should be is less clear. And this is where the subject becomes contentious and opinions diverge because, somewhat surprisingly, what really represents a human embryo has so far not been resolved.

"Prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation."

In 2002, Howard W. Jones Jr., widely considered the "father" of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the U.S., argued in a widely acclaimed article titled "What is an embryo?" that a precondition for the definition of a human embryo was successful implantation. Only once implantation established a biological unit between embryo and mother, could a relatively small number of human cells be considered a human embryo.

Because he felt strongly that human embryos, indeed, deserve special considerations, and should receive those during IVF, he pointed out that, even inside a woman's body, most human embryos (in contrast to other species) never implant and, therefore, are never given a chance at human life. Consequently, he reasoned that prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation.

"One cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is."

This difference, he felt, should also be reflected in scientific language, proposing that embryos prior to implantation in daily IVF practice be called "pre-embryos," with the term "embryo" reserved for post-implantation-stage embryos. Then still unknown to Jones, recent research findings support this viewpoint, since genetic profiles of pre- and post-implantation stage embryos greatly differ.

In an analogy to nature, which in humans allows implantation of only a small minority of naturally generated pre-embryos, IVF centers around the world routinely discard large numbers of pre-embryos, judged inadequate for producing normal pregnancies. Jones' suggestion that only post-implantation embryos should be considered embryos deserving of special considerations, therefore, not only appears prescient and considerate of current IVF practices, but grounded in scientific reality. One, therefore, cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is.

"Much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking."

In 1984, a British ethics committee issued the Warnock Report, which still today prohibits scientists worldwide from studying human embryos in a lab beyond 14 days from fertilization or past formation of the so-called primitive streak, whichever comes first. Well-meaning in its day, its intent was to apply special considerations to human pre-embryos by protecting them from the potential of "feeling pain," once the primitive streak arose on day-15 of development. Formation of the primitive streak signifies a process known as gastrulation, when a subset of cells from the inner cell mass of the pre-embryo are transformed into the three germ layers that comprise all tissues of the developing embryo: The ectoderm, which gives rise to the nervous system; the mesoderm, which gives rise to the circulatory system, muscle, and kidneys; and the endoderm which gives rise to the interior lining of the digestive and respiratory tracts, among other tissues.

That pre-embryos may feel pain at that stage of development was far-fetched in 1984; in view of what we have learned about early human embryology in the 33 years since, it remains untenable today. And, yet, scientists all over the world remain bound by the ethical constraints imposed by the Warnock Report.

A similar ethical paradox exists today for guidelines affecting huge numbers of so-called "abandoned" cryopreserved embryos, often stored ad infinitum in IVF centers all over the world. These are pre-embryos, whose "parents" are no longer responsive to queries from their IVF centers. Current U.S. guidelines allow the disposal of such pre-embryos but prohibit their use in research that may benefit mankind. One, however, wonders whether disposal of huge numbers of abandoned embryos is really more ethical than their use in potentially life-saving human research?

That much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is, indeed, guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking, is also demonstrated by recently expressed concern about so-called "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos. Though both of these terms suggest impending ability to create human embryos from synthetic building blocks, this is not what these terms are meant to describe (such abilities also are not on the horizon). They also do not describe abilities to create gametes (i.e., eggs and sperm) from somatic cells by reprogramming adult peripheral cells, which has already been successfully done in mice by Japanese investigators, leading to the creation of healthy embryos and births and three generations of healthy pubs. Such an approach is at least conceivable as an upcoming infertility treatment.

"A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos."

What all of this noise is really about is the discovery that, as several Rockefeller University investigators recently noted, "Cells have an intrinsic ability to self-assemble and self-organize into complex and functional tissues and organs." Investigators have taken advantage of this ability by creating in the lab so-called "organoids" from accumulations of individual embryonic stem cells. They are defined by three characteristics: (i) they contain a variety of cell types and tissue layers, all typical for a given organ; (ii) these cells are organized similarly to their organization in a specific organ; and (iii) the organoid mimics functions of the organ.

Several other biologists from the Cincinnati Children Hospital Medical Center recently noted that in the last five years, quite a variety of human stem cell-derived organoids, including all three germ layers, have been generated by different research groups around the world, thereby establishing new human model systems that can be used outside the body, in a dish, to investigate otherwise difficult-to-approach organs. Interestingly, they can also be used to investigate early stages of human embryological development.

A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos and, therefore, were given the name "embroids." Though clearly not embryos (the only thing they had in common with human embryos were cell types), they were nevertheless awarded in at least one article the identity of "artificial embryos," which "no one knows how to handle." As Howard Jones so correctly noted, with the word embryo often comes undeserved reverence.

"Any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided; it is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect."

Artificial embryos, therefore, do not exist. Organoids that resemble embryos (i.e., "embroids"), while potentially very useful research objects in studies of early human embryonic cell organization and lineage development, are not embryos--not even pre-embryos. Special considerations for "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos, as recently advocated by some scientists, therefore, appear ethically undeserved. How misdirected and forced some of these efforts are is probably best demonstrated by a recent publication in which a group of Harvard University investigators proposed the term "synthetic human entities with embryo-like features" or SHEEFS" in place of "organoids." Preferably, however, in describing these laboratory-created entities, any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided. It is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect.

Clinical reproductive medicine and reproductive biology, for valid ethical reasons, but also because of myths, misperceptions and, sometimes, outright misrepresentations of facts for political reasons, are under more public scrutiny than most other science areas. Yet, at least in the realm of biomedical research, nothing appears more important than better understanding the first few days of human embryo development. A recent study involving genetic editing of human embryos, reported by British investigators in Nature, once again confirmed what biologist have known for some time: No animal model faithfully recapitulates most of human developmental origins. The most important secrets nature still has to tell us, will not be revealed through mouse or other animal studies. We will discover them only through the study of early-stage human embryos – and we, therefore, should not limit the use of lab-grown organoids to help further that research.

Understanding early human development "will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine."

As Howard Jones intuitively noticed, words matter. Appropriate and uniformly accepted definitions and terms are not only essential for scientific communications but, within the context of human reproduction, often elicit strong emotional reactions, and are easily misappropriated by those opposed to most interventions into human reproduction.

Who does not recall the early days of IVF in the late 1970s, when even reputable news outlets raised the specter of Frankenstein monsters created through the IVF process? Millions of IVF births later, a Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology was in 2010 finally awarded to the biologist Robert Edwards who, together with the gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, reported the first live birth through IVF on July 25, 1978. Many more awards are still waiting for recipients who through the study of early human embryo development will discover how cell fate is determined and cells acquire highly specific functions; how rapid cell proliferation takes place and, when required, stops; why chromosomal abnormalities are so common in early stage embryos and what their function may be.

Those who will discover these and many other important answers, will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine. Learning how to control cell proliferation, for example, will likely revolutionize cancer therapy; I started my research career in biology with a study published in 1980 of "common denominators of pregnancy and malignancy." If regulatory prohibitions are not allowed to interfere in rapidly progressing research opportunities involving organoids and pre-embryos, we will, finally, see the circle closing, with the most rewarding benefits for mankind ever achieved through biological research.

Editor's Note: Read a different viewpoint here written by one of the world's top experts on the ethics of stem cell research.

The upcoming vaccine is changing the way we look at treating one of the country’s deadliest cancers.

Last week, researchers at the University of Oxford announced that they have received funding to create a brand new way of preventing ovarian cancer: A vaccine. The vaccine, known as OvarianVax, will teach the immune system to recognize and destroy mutated cells—one of the earliest indicators of ovarian cancer.

Understanding Ovarian Cancer

Despite advancements in medical research and treatment protocols over the last few decades, ovarian cancer still poses a significant threat to women’s health. In the United States alone, more than 12,0000 women die of ovarian cancer each year, and only about half of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer survive five or more years past diagnosis. Unlike cervical cancer, there is no routine screening for ovarian cancer, so it often goes undetected until it has reached advanced stages. Additionally, the primary symptoms of ovarian cancer—frequent urination, bloating, loss of appetite, and abdominal pain—can often be mistaken for other non-cancerous conditions, delaying treatment.

An American woman has roughly a one percent chance of developing ovarian cancer throughout her lifetime. However, these odds increase significantly if she has inherited mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Women who carry these mutations face a 46% lifetime risk for ovarian and breast cancers.

An Unlikely Solution

To address this escalating health concern, the organization Cancer Research UK has invested £600,000 over the next three years in research aimed at creating a vaccine, which would destroy cancerous cells before they have a chance to develop any further.

Researchers at the University of Oxford are at the forefront of this initiative. With funding from Cancer Research UK, scientists will use tissue samples from the ovaries and fallopian tubes of patients currently battling ovarian cancer. Using these samples, University of Oxford scientists will create a vaccine to recognize certain proteins on the surface of ovarian cancer cells known as tumor-associated antigens. The vaccine will then train that person’s immune system to recognize the cancer markers and destroy them.

The next step

Once developed, the vaccine will first be tested in patients with the disease, to see if their ovarian tumors will shrink or disappear. Then, the vaccine will be tested in women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations as well as women in the general population without genetic mutations, to see whether the vaccine can prevent the cancer altogether.

While the vaccine still has “a long way to go,” according to Professor Ahmed Ahmed, Director of Oxford University’s ovarian cancer cell laboratory, he is “optimistic” about the results.

“We need better strategies to prevent ovarian cancer,” said Ahmed in a press release from the University of Oxford. “Currently, women with BRCA1/2 mutations are offered surgery which prevents cancer but robs them of the chance to have children afterward.

Teaching the immune system to recognize the very early signs of cancer is a tough challenge. But we now have highly sophisticated tools which give us real insights into how the immune system recognizes ovarian cancer. OvarianVax could offer the solution.”

How sharing, hearing, and remembering positive stories can help shape our brains for the better

Across cultures and through millennia, human beings have always told stories. Whether it’s a group of boy scouts around a campfire sharing ghost stories or the paleolithic Cro-Magnons etching pictures of bison on cave walls, researchers believe that storytelling has been universal to human beings since the development of language.

But storytelling was more than just a way for our ancestors to pass the time. Researchers believe that storytelling served an important evolutionary purpose, helping humans learn empathy, share important information (such as where predators were or what berries were safe to eat), as well as strengthen social bonds. Quite literally, storytelling has made it possible for the human race to survive.

Today, neuroscientists are discovering that storytelling is just as important now as it was millions of years ago. Particularly in sharing positive stories, humans can more easily form relational bonds, develop a more flexible perspective, and actually grow new brain circuitry that helps us survive. Here’s how.

How sharing stories positively impacts the brain

When human beings share stories, it increases the levels of certain neurochemicals in the brain, neuroscientists have found. In a 2021 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Swedish researchers found that simply hearing a story could make hospitalized children feel better, compared to other hospitalized children who played a riddle game for the same amount of time. In their research, children in the intensive care unit who heard stories for just 30 minutes had higher levels of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes positive feelings and is linked to relaxation, trust, social connectedness, and overall psychological stability. Furthermore, the same children showed lower levels of cortisol, a hormone associated with stress. Afterward, the group of children who heard stories tended to describe their hospital experiences more positively, and even reported lower levels of pain.

Annie Brewster, MD, knows the positive effect of storytelling from personal experience. An assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and the author of The Healing Power of Storytelling: Using Personal Narrative to Navigate Illness, Trauma, and Loss, Brewster started sharing her personal experience with chronic illness after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2001. In doing so, Brewster says it has enabled her to accept her diagnosis and integrate it into her identity. Brewster believes so much in the power of hearing and sharing stories that in 2013 she founded Health Story Collaborative, a forum for others to share their mental and physical health challenges.“I wanted to hear stories of people who had found ways to move forward in positive ways, in spite of health challenges,” Brewster said. In doing so, Brewster believes people with chronic conditions can “move closer to self-acceptance and self-love.”

While hearing and sharing positive stories has been shown to increase oxytocin and other “feel good” chemicals, simply remembering a positive story has an effect on our brains as well. Mark Hoelterhoff, PhD, a lecturer in clinical psychology at the University of Edinburgh, recalling and “savoring” a positive story, thought, or feedback “begins to create new brain circuitry—a new neural network that’s geared toward looking for the positive,” he says. Over time, other research shows, savoring positive stories or thoughts can literally change the shape of your brain, hard-wiring someone to see things in a more positive light.How stories can change your behavior

In 2009, Paul Zak, PhD, a neuroscientist and professor at Claremont Graduate University, set out to measure how storytelling can actually change human behavior for the better. In his study, Zak wanted to measure the behavioral effects of oxytocin, and did this by showing test subjects two short video clips designed to elicit an emotional response.

In the first video they showed the study participants, a father spoke to the camera about his two-year-old son, Ben, who had been diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The father told the audience that he struggled to connect with and enjoy Ben, as Ben had only a few months left to live. In the end, the father finds the strength to stay emotionally connected to his son until he dies.

The second video clip, however, was much less emotional. In that clip, the same father and son are shown spending the day at the zoo. Ben is only suggested to have cancer (he is bald from chemotherapy and referred to as a ‘miracle’, but the cancer isn’t mentioned directly). The second story lacked the dramatic narrative arc of the first video.

Zak’s team took blood before and after the participants watched one of the two videos and found that the first story increased the viewers’ cortisol and oxytocin, suggesting that they felt distress over the boy’s diagnosis and empathy toward the boy and his father. The second narrative, however, didn’t increase oxytocin or cortisol at all.

But Zak took the experiment a step further. After the movie clips, his team gave the study participants a chance to share money with a stranger in the lab. The participants who had an increase in cortisol and oxytocin were more likely to donate money generously. The participants who had increased cortisol and oxytocin were also more likely to donate money to a charity that works with children who are ill. Zak also found that the amount of oxytocin that was released was correlated with how much money people felt comfortable giving—in other words, the more oxytocin that was released, the more generous they felt, and the more money they donated.

How storytelling strengthens our bond with others

Sharing, hearing, and remembering stories can be a powerful tool for social change–not only in the way it changes our brain and our behavior, but also because it can positively affect our relationships with other people

Emotional stimulation from telling stories, writes Zak, is the foundation for empathy, and empathy strengthens our relationships with other people. “By knowing someone’s story—where they come from, what they do, and who you might know in common—relationships with strangers are formed.”

But why are these relationships important for humanity? Because human beings can use storytelling to build empathy and form relationships, it enables them to “engage in the kinds of large-scale cooperation that builds massive bridges and sends humans into space,” says Zak.

Storytelling, Zak found, and the oxytocin release that follows, also makes people more sensitive to social cues. This sensitivity not only motivates us to form relationships, but also to engage with other people and offer help, particularly if the other person seems to need help.

But as Zak found in his experiments, the type of storytelling matters when it comes to affecting relationships. Where Zak found that storytelling with a dramatic arc helps release oxytocin and cortisol, enabling people to feel more empathic and generous, other researchers have found that sharing happy stories allows for greater closeness between individuals and speakers. A group of Chinese researchers found that, compared to emotionally-neutral stories, happy stories were more “emotionally contagious.” Test subjects who heard happy stories had greater activation in certain areas of their brains, experienced more significant, positive changes in their mood, and felt a greater sense of closeness between themselves and the speaker.

“This finding suggests that when individuals are happy, they become less self-focused and then feel more intimate with others,” the authors of the study wrote. “Therefore, sharing happiness could strengthen interpersonal bonding.” The researchers went on to say that this could lead to developing better social networks, receiving more social support, and leading more successful social lives.

Since the start of the COVID pandemic, social isolation, loneliness, and resulting mental health issues have only gotten worse. In light of this, it’s safe to say that hearing, sharing, and remembering stories isn’t just something we can do for entertainment. Storytelling has always been central to the human experience, and now more than ever it’s become something crucial for our survival.

Want to know how you can reap the benefits of hearing happy stories? Keep an eye out for Upworthy’s first book, GOOD PEOPLE: Stories from the Best of Humanity, published by National Geographic/Disney, available on September 3, 2024. GOOD PEOPLE is a much-needed trove of life-affirming stories told straight from the heart. Handpicked from Upworthy’s community, these 101 stories speak to the breadth, depth, and beauty of the human experience, reminding us we have a lot more in common than we realize.