“Synthetic Embryos”: The Wrong Term For Important New Research

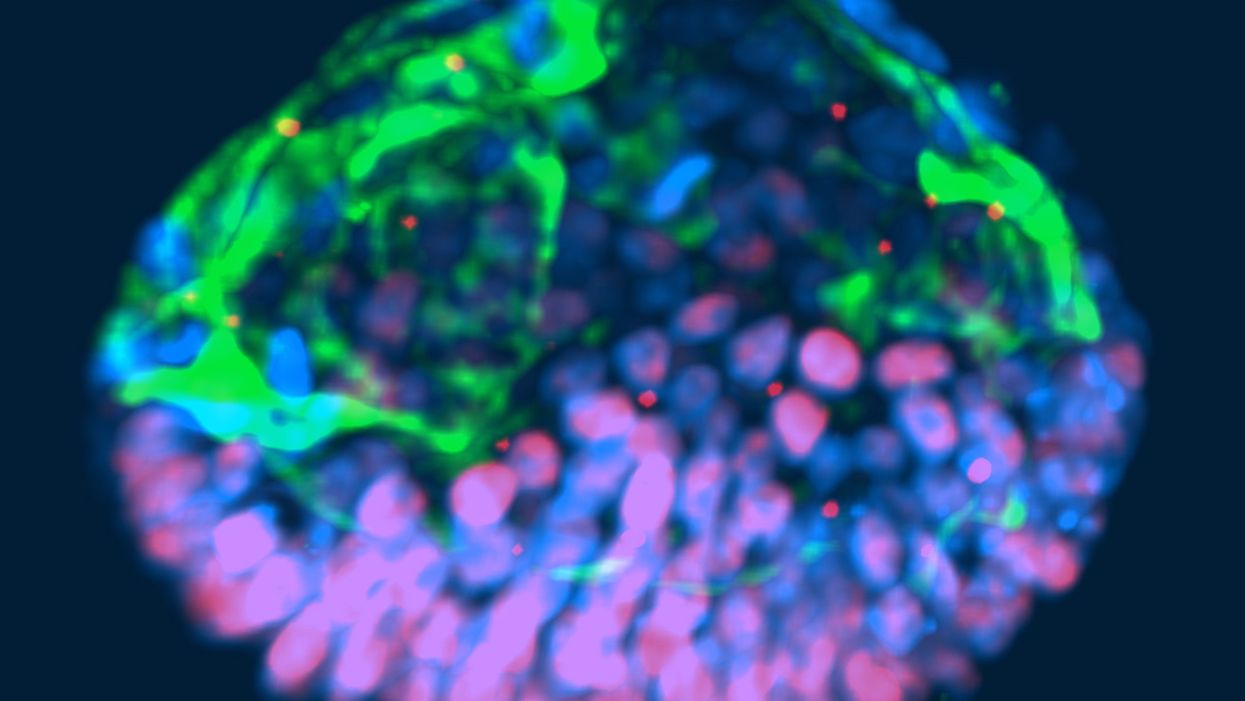

This fluorescent image shows a representative post-implantation amniotic sac embroid.

As a subject of research, an unusual degree of consensus appears to exist among scientists, politicians and the public about human embryos being deserving of special considerations. But what those special considerations should be is less clear. And this is where the subject becomes contentious and opinions diverge because, somewhat surprisingly, what really represents a human embryo has so far not been resolved.

"Prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation."

In 2002, Howard W. Jones Jr., widely considered the "father" of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the U.S., argued in a widely acclaimed article titled "What is an embryo?" that a precondition for the definition of a human embryo was successful implantation. Only once implantation established a biological unit between embryo and mother, could a relatively small number of human cells be considered a human embryo.

Because he felt strongly that human embryos, indeed, deserve special considerations, and should receive those during IVF, he pointed out that, even inside a woman's body, most human embryos (in contrast to other species) never implant and, therefore, are never given a chance at human life. Consequently, he reasoned that prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation.

"One cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is."

This difference, he felt, should also be reflected in scientific language, proposing that embryos prior to implantation in daily IVF practice be called "pre-embryos," with the term "embryo" reserved for post-implantation-stage embryos. Then still unknown to Jones, recent research findings support this viewpoint, since genetic profiles of pre- and post-implantation stage embryos greatly differ.

In an analogy to nature, which in humans allows implantation of only a small minority of naturally generated pre-embryos, IVF centers around the world routinely discard large numbers of pre-embryos, judged inadequate for producing normal pregnancies. Jones' suggestion that only post-implantation embryos should be considered embryos deserving of special considerations, therefore, not only appears prescient and considerate of current IVF practices, but grounded in scientific reality. One, therefore, cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is.

"Much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking."

In 1984, a British ethics committee issued the Warnock Report, which still today prohibits scientists worldwide from studying human embryos in a lab beyond 14 days from fertilization or past formation of the so-called primitive streak, whichever comes first. Well-meaning in its day, its intent was to apply special considerations to human pre-embryos by protecting them from the potential of "feeling pain," once the primitive streak arose on day-15 of development. Formation of the primitive streak signifies a process known as gastrulation, when a subset of cells from the inner cell mass of the pre-embryo are transformed into the three germ layers that comprise all tissues of the developing embryo: The ectoderm, which gives rise to the nervous system; the mesoderm, which gives rise to the circulatory system, muscle, and kidneys; and the endoderm which gives rise to the interior lining of the digestive and respiratory tracts, among other tissues.

That pre-embryos may feel pain at that stage of development was far-fetched in 1984; in view of what we have learned about early human embryology in the 33 years since, it remains untenable today. And, yet, scientists all over the world remain bound by the ethical constraints imposed by the Warnock Report.

A similar ethical paradox exists today for guidelines affecting huge numbers of so-called "abandoned" cryopreserved embryos, often stored ad infinitum in IVF centers all over the world. These are pre-embryos, whose "parents" are no longer responsive to queries from their IVF centers. Current U.S. guidelines allow the disposal of such pre-embryos but prohibit their use in research that may benefit mankind. One, however, wonders whether disposal of huge numbers of abandoned embryos is really more ethical than their use in potentially life-saving human research?

That much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is, indeed, guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking, is also demonstrated by recently expressed concern about so-called "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos. Though both of these terms suggest impending ability to create human embryos from synthetic building blocks, this is not what these terms are meant to describe (such abilities also are not on the horizon). They also do not describe abilities to create gametes (i.e., eggs and sperm) from somatic cells by reprogramming adult peripheral cells, which has already been successfully done in mice by Japanese investigators, leading to the creation of healthy embryos and births and three generations of healthy pubs. Such an approach is at least conceivable as an upcoming infertility treatment.

"A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos."

What all of this noise is really about is the discovery that, as several Rockefeller University investigators recently noted, "Cells have an intrinsic ability to self-assemble and self-organize into complex and functional tissues and organs." Investigators have taken advantage of this ability by creating in the lab so-called "organoids" from accumulations of individual embryonic stem cells. They are defined by three characteristics: (i) they contain a variety of cell types and tissue layers, all typical for a given organ; (ii) these cells are organized similarly to their organization in a specific organ; and (iii) the organoid mimics functions of the organ.

Several other biologists from the Cincinnati Children Hospital Medical Center recently noted that in the last five years, quite a variety of human stem cell-derived organoids, including all three germ layers, have been generated by different research groups around the world, thereby establishing new human model systems that can be used outside the body, in a dish, to investigate otherwise difficult-to-approach organs. Interestingly, they can also be used to investigate early stages of human embryological development.

A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos and, therefore, were given the name "embroids." Though clearly not embryos (the only thing they had in common with human embryos were cell types), they were nevertheless awarded in at least one article the identity of "artificial embryos," which "no one knows how to handle." As Howard Jones so correctly noted, with the word embryo often comes undeserved reverence.

"Any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided; it is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect."

Artificial embryos, therefore, do not exist. Organoids that resemble embryos (i.e., "embroids"), while potentially very useful research objects in studies of early human embryonic cell organization and lineage development, are not embryos--not even pre-embryos. Special considerations for "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos, as recently advocated by some scientists, therefore, appear ethically undeserved. How misdirected and forced some of these efforts are is probably best demonstrated by a recent publication in which a group of Harvard University investigators proposed the term "synthetic human entities with embryo-like features" or SHEEFS" in place of "organoids." Preferably, however, in describing these laboratory-created entities, any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided. It is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect.

Clinical reproductive medicine and reproductive biology, for valid ethical reasons, but also because of myths, misperceptions and, sometimes, outright misrepresentations of facts for political reasons, are under more public scrutiny than most other science areas. Yet, at least in the realm of biomedical research, nothing appears more important than better understanding the first few days of human embryo development. A recent study involving genetic editing of human embryos, reported by British investigators in Nature, once again confirmed what biologist have known for some time: No animal model faithfully recapitulates most of human developmental origins. The most important secrets nature still has to tell us, will not be revealed through mouse or other animal studies. We will discover them only through the study of early-stage human embryos – and we, therefore, should not limit the use of lab-grown organoids to help further that research.

Understanding early human development "will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine."

As Howard Jones intuitively noticed, words matter. Appropriate and uniformly accepted definitions and terms are not only essential for scientific communications but, within the context of human reproduction, often elicit strong emotional reactions, and are easily misappropriated by those opposed to most interventions into human reproduction.

Who does not recall the early days of IVF in the late 1970s, when even reputable news outlets raised the specter of Frankenstein monsters created through the IVF process? Millions of IVF births later, a Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology was in 2010 finally awarded to the biologist Robert Edwards who, together with the gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, reported the first live birth through IVF on July 25, 1978. Many more awards are still waiting for recipients who through the study of early human embryo development will discover how cell fate is determined and cells acquire highly specific functions; how rapid cell proliferation takes place and, when required, stops; why chromosomal abnormalities are so common in early stage embryos and what their function may be.

Those who will discover these and many other important answers, will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine. Learning how to control cell proliferation, for example, will likely revolutionize cancer therapy; I started my research career in biology with a study published in 1980 of "common denominators of pregnancy and malignancy." If regulatory prohibitions are not allowed to interfere in rapidly progressing research opportunities involving organoids and pre-embryos, we will, finally, see the circle closing, with the most rewarding benefits for mankind ever achieved through biological research.

Editor's Note: Read a different viewpoint here written by one of the world's top experts on the ethics of stem cell research.

Niklas Anzinger is the founder of Infinita VC based in the charter city of Prospera in Honduras. Infinita focuses on a new trend of charter cities and other forms of alternative jurisdictions. Healso hosts a podcast about how to accelerate the future by unblocking “stranded technologies”.This spring he was a part of the network city experiment Zuzalu spearheaded by Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin where a few hundred invited guests from the spheres of longevity, biotechnology, crypto, artificial intelligence and investment came together to form a two-monthlong community. It has been described as the world’s first pop-up city. Every morning Vitalians would descend on a long breakfast—the menu had been carefully designed by famed radical longevity self-experimenter Bryan Johnson—and there is where I first met Anzinger who told me about Prospera. Intrigued to say the least, I caught up with him later the same week and the following is a record of our conversation.

Q. We are sitting here in the so-called pop-up network state Zuzalu temporarily realized in the village of Lusticia Bay by the beautiful Mediterranean Sea. To me this is an entirely new concept: What is a network state?

A. A network state is a highly aligned online community that has a level of in-person civility; it crowd-funds territory, and it eventually seeks diplomatic recognition. In a way it's about starting a new country. The term was coined by the crypto influencer and former CTO of Coinbase Balaji Srinivasan in a book by the same title last year [2022]. What many people don't know is that it is a more recent addition or innovation in a space called competitive governance. The idea is that you have multiple jurisdictions competing to provide you services as a customer. When you have competition among governments or government service providers, these entities are forced to provide you with a better service instead of the often worse service at higher prices or higher taxes that we're currently getting. The idea went from seasteading, which was hardly feasible because of costs, to charter cities getting public/private partnerships with existing governments and a level of legal autonomy, to special economic zones, to now network states.

Q. How do network states compare to charter cities and similar jurisdictions?

A. Charter cities and special economic zones were legal forks from other existing states. Dubai, Shenzhen in China, to some degree Hong Kong, to some degree Singapore are some examples. There's a host of other charter cities, one of which I'm based in myself, which is Prospera located in Honduras on the island Roatán. Charter cities provide the full stack of governance; they provide new laws and regulations, business registration, tax codes and governance services, Estonia style: you log on to the government platform and you get services as a citizen.

When conceptualizing network states, Balagi Srinivasan turns the idea of a charter city a bit on its head: he doesn't want to start with this full stack because it's still very hard to get these kinds of partnerships with government. It's very expensive and requires lots of experience and lots of social capital. He is saying that network states could instead start as an online community. They could have a level of alignment where they trade with each other; they have their own economy; they meet in person in regular gatherings like we're doing here in Zuzulu for two months, and then they negotiate with existing governments or host cities to get a certain degree of legal autonomy that is centered around a moral innovation. So, his idea is: don't focus on building a completely new country or city; focus on a moral innovation.

Q. What would be an example of such a moral innovation?

A. An example would be longevity—life is good; death is bad—let's see what we can do to foster progress around that moral innovation and see how we can get legal forks from the existing system that allow us to accelerate progress in that area. There is an increasing realization in the science that there are hallmarks of aging and that aging is a cause of other diseases like cancer, ALS or Alzheimer's. But aging is not recognized as a disease by the FDA in the United States and in most countries around the world, so it's very hard to get scientific funding for biotechnology that would attack the hallmarks of aging and allow us potentially to reverse aging and extend life. This is a significant shortcoming of existing government systems that groups such as the ones that have come together here in Montenegro are now seeking alternatives too. Charter cities and now network states are such alternatives.

Q. Would it not be better to work within the current systems, and try to improve them, rather than abandon them for new experimental jurisdictions?

A. There are numerous failures of public policies. These failures are hard, if not impossible, to reverse, because as soon as you have these policies, you have entrenched interests who benefit from the regulations. The only way to disrupt incumbent industries is with start-ups, but the way the system is set up makes it excessively hard for such start-ups to become big companies. In fact, larger companies are weaponizing the legal system against small companies, because they can afford the lawyers and the fixed cost of compliance.

I don't believe that our institutions in many developed countries are beyond hope. I just think it's easier to change them if you could point at successful examples. ‘Hey, this country or this zone is already doing it very successfully’; if they can extend people’s lifespan by 10 years, if they can reduce maternal mortality, and if they have a massive medical tourism where people come back healthier, then that is just very embarrassing for the FDA.

Q. Perhaps a comparison here would be the relationship between Hong Kong and China?

A. Correct, so having Hong Kong right in front of your door … ‘Hey, this capitalism thing seems to work, why don't we try it here?’ It was due to the very bold leadership by Deng Xiaoping that they experimented with it in the development zone of Shenzhen. It worked really well and then they expanded with more special economic zones that also worked.

Próspera is a private city and special economic zone on the island of Roatán in the Central American state of Honduras.

Q. Tell us about Prospera, the charter city in Honduras, that you are intimately connected with.

A. Honduras is a very poor country. It has a lot of crime, never had a single VC investment, and has a GDP per capita of 2,000 per year. Honduras has suffered tremendously. The goal of these special economic zones is to bring in economic development. That's their sole purpose. It's a homegrown innovation from Honduras that started in 2009 with a very forward-thinking statesman, Octavio Sanchez, who was the chief of staff to the president of Honduras, and then president. He had his own ideas about making Honduras a more decentralized system, where more of the power lies in the municipalities.

Inspired by the ideas of Nobel laureate economist Paul Romer, who gave a famous Ted Talk in 2009 about charter cities, Sanchez initiated a process that lasted for years and eventually led to the creation of a special economic zone legal regime that’s anchored in the Hunduran constitution that provides the highest legal autonomy in the world to these zones. There are today three special economic zones approved by the Honduran government: Prospera, Ciudad Morazan and Orchidea.

Q. How did you become interested and then involved in Prospera?

A. I read about it first in an article by Scott Alexander, a famous rationalist blogger, who wrote a very long article about Prospera, and I thought, this is amazing! Then I came to Prospera and I found it to be one of the most if not the most exciting project in the world going on right now and that it also opened my heart to the country and its people. Most of my friends there are Honduran, they have been working on this for 10 or more years. They want to remake Honduras and put it on the map as the place in the world where this legal and governance innovation started.

Q. To what extent is Prospera autonomous relative to the Honduran government?

A. What's interesting about the Honduran model is that it's anchored within the Honduran constitution, and it has a very clear framework for what's possible and what's not possible, and what's possible ensures the highest degree of legal autonomy anywhere seen in the world. Prospera has really pushed the model furthest in creating a common law-based polycentric legal system. The idea is that you don't have a legislature, instead you have common law and it's based on the best practice common law principles that a legal scholar named Tom W. Bell created.

One of the core ideas is that as a business you're not obligated to follow one regulatory monopoly like the FDA. You have regulatory flexibility so you can choose what you're regulated under. So, you can say: ‘if I do a medical clinic, I do it under Norwegian law here’. And you even have the possibility to amend it a bit. You're still required to have liability insurance, and have to agree to binding arbitration in case there's a legal dispute. And your insurance has to approve you. So, under that model the insurance becomes the regulator and they regulate through prices. The limiting factor is criminal law; Honduran criminal law fully applies. So does immigration law. And we pay taxes.

Q. Is there also an idea of creating a kind of healthy living there, and encourage medical tourism?

A. Yes, we specifically look for legal advantages in autonomy around creating new drugs, doing clinical trials, doing self-medication and experimentation. There is a stem cell clinic here and they're doing clinical trials. The island of Roatán is very easily accessible for American tourists. It's a beautiful island, and it's for regulatory reasons hard to do stem cell therapies in the United States, so they're flying in patients from the United States. Most of them are very savvy and often have PhDs in biotech and are able to assess the risk for themselves of taking drugs and doing clinical trials. We're also going to get a wellness center, and there have been ideas around establishing a peptide clinic and a compound pharmacy and things like that. We are developing a healthcare ecosystem.

Q. This kind of experimental tourism raises some ethical issues. What happens if patients are harmed? And what are the moral implications for society of these new treatments?

A. As a moral principle we believe in medical freedom: people have rights over their bodies, even at the (informed) risk of harm to themselves if no unconsenting third-parties are harmed; this is a fundamental right currently not protected effectively.

What we do differently is not changing ethical norms around safety and efficacy, we’re just changing the institutional setup. Instead of one centralized bureaucracy, like the FDA, we have regulatory pluralism that allows different providers of safety and efficacy to compete under market rules. Like under any legal system, common law in Prospera punishes malpractice, fraud, murder etc. This system will still produce safe and effective drugs, and it will still work with common sense legal notions like informed consent and liability for harm. There are regulations for medical practice, there is liability insurance and things like that. It will just do so more efficiently than the current way of doing things (unless it won’t, in which case it will change and evolve – or fail).

A direct moral benefit ´to what we do is that we increase accessibility. Typical gene therapies on the market cost $1 million dollars in the US. The gene therapy developed in Prospera costs $25,000. As to concern about whether such treatments are problematic, we do not share this perspective. We are for advancing science responsibly and we believe that both individuals and society stand to gain from improving the resiliency of the human body through advanced biotechnology.

Q. How does Prospera relate to the local Honduran population?

A. I think it's very important that our projects deliver local benefits and that they're well anchored in local communities. Because when you go to a new place, you're seen as a foreigner, and you're seen as potentially a danger or a threat. The most important thing for Prospera and Ciudad Morazan is to show we're creating jobs; we're creating employment; we're improving people's lives on the ground. Prospera is directly and indirectly employing 1,100 people. More than 2/3 of the people who are working for Prospera are Honduran. It has a lot of local service workers from the island, and it has educated Hondurans from the mainland for whom it's an alternative to going to the United States.

Q. What makes a good Prosperian citizen?

A. People in Prospera are very entrepreneurial. They're opening companies on a small scale. For example, Vehinia, who is the cook in the kitchen at Prospera, she's from the neighboring village and she started an NGO that is now funding a school where children from the local village can go to instead of a school that's 45 minutes away. There's very much a spirit of ‘let's exchange and trade with each other’. Some people might see that as a bit too commercial, but that's something about the culture that people accept and that people see as a good thing.

Q. Five years from now, if everything goes well, what do we see in Prospera?

A. I think Prospera will have at least 10,000 residents and I think Honduras hopefully will have more zones. There could be zones with a thriving industrial sector and sort of a labor-intensive economy and some that are very strong in pharmaceuticals, there could also be other zones for synthetic biology, and other zones focused on agriculture. The zones of Prospera, Ciudad Morazan and Orchidea are already showing the results we want to see, the results that we will eventually be measured by, and I'm tremendously excited about Honduras.

How to Measure Your Stress, with Dr. Rosalind Picard

Today’s podcast guest is Rosalind Picard, a researcher, inventor named on over 100 patents, entrepreneur, author, professor and engineer. When it comes to the science related to endowing computer software with emotional intelligence, she wrote the book. It’s published by MIT Press and called Affective Computing.

Dr. Picard is founder and director of the MIT Media Lab’s Affective Computing Research Group. Her research and engineering contributions have been recognized internationally. For example, she received the 2022 International Lombardy Prize for Computer Science Research, considered by many to be the Nobel prize in computer science.

Through her research and companies, Dr. Picard has developed wearable sensors, algorithms and systems for sensing, recognizing and responding to information about human emotion. Her products are focused on using fitness trackers to advance clinical quality treatments for a range of conditions.

Meanwhile, in just the past few years, numerous fitness tracking companies have released products with their own stress sensors and systems. You may have heard about Fitbit’s Stress Management Score, or Whoop’s Stress Monitor – these features and apps measure things like your heart rhythm and a certain type of invisible sweat to identify stress. They’re designed to raise awareness about forms of stress such as anxieties and anger, and suggest strategies like meditation to relax in real time when stress occurs.

But how well do these off-the-shelf gadgets work? There’s no one more knowledgeable and experienced than Rosalind Picard to explain the science behind these stress features, what they do exactly, how they might be able to help us, and their current shortcomings.

Dr. Picard is a member of the National Academy of Engineering and a Fellow of the National Academy of Inventors, and a popular speaker who’s given over a hundred invited keynote talks and a TED talk with over 2 million views. She holds a Bachelors in Electrical Engineering from Georgia Tech, and Masters and Doctorate degrees in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from MIT. She lives in Newton, Massachusetts with her husband, where they’ve raised three sons.

In our conversation, we discuss stress scores on fitness trackers to improve well-being. She describes the difference between commercial products that might help people become more mindful of their health and products that are FDA approved and really capable of advancing the science. We also talk about several fascinating findings and concepts discovered in Dr. Picard’s lab including the multiple arousal theory, a phenomenon you’ll want to hear about. And we explore the complexity of stress, one reason it’s so tough to measure. For example, many forms of stress are actually good for us. Can fitness trackers tell the difference between stress that’s healthy and unhealthy?

Show links:

- Dr. Picard’s book, Affective Computing

- Dr. Picard’s bio

- Dr. Picard on Twitter

- Dr. Picard’s company, Empatica - https://www.empatica.com/ - The FDA-cleared Empatica Health Monitoring Platform provides accurate, continuous health insights for researchers and clinicians, collected in the real world

- Empatica Twitter

- Dr. Picard and her team have published hundreds of peer-reviewed articles across AI, Machine Learning, Affective Computing, Digital Health, and Human-computer interaction.

- Dr. Picard’s TED talk

Rosalind Picard