Trading syphilis for malaria: How doctors treated one deadly disease by infecting patients with another

In the 1920s, doctors induced a high fever in patients - so called "fever therapy" - as a way to help them recover from syphilis, though it involved ethical problems.

If you had lived one hundred years ago, syphilis – a bacterial infection spread by sexual contact – would likely have been one of your worst nightmares. Even though syphilis still exists, it can now be detected early and cured quickly with a course of antibiotics. Back then, however, before antibiotics and without an easy way to detect the disease, syphilis was very often a death sentence.

To understand how feared syphilis once was, it’s important to understand exactly what it does if it’s allowed to progress: the infections start off as small, painless sores or even a single sore near the vagina, penis, anus, or mouth. The sores disappear around three to six weeks after the initial infection – but untreated, syphilis moves into a secondary stage, often presenting as a mild rash in various areas of the body (such as the palms of a person’s hands) or through other minor symptoms. The disease progresses from there, often quietly and without noticeable symptoms, sometimes for decades before it reaches its final stages, where it can cause blindness, organ damage, and even dementia. Research indicates, in fact, that as much as 10 percent of psychiatric admissions in the early 20th century were due to dementia caused by syphilis, also known as neurosyphilis.

Like any bacterial disease, syphilis can affect kids, too. Though it’s spread primarily through sexual contact, it can also be transmitted from mother to child during birth, causing lifelong disability.

The poet-physician Aldabert Bettman, who wrote fictionalized poems based on his experiences as a doctor in the 1930s, described the effect syphilis could have on an infant in his poem Daniel Healy:

I always got away clean

when I went out

With the boys.

The night before

I was married

I went out,—But was not so fortunate;

And I infected

My bride.

When little Daniel

Was born

His eyes discharged;

And I dared not tell

That because

I had seen too much

Little Daniel sees not at all

Given the horrors of untreated syphilis, it’s maybe not surprising that people would go to extremes to try and treat it. One of the earliest remedies for syphilis, dating back to 15th century Naples, was using mercury – either rubbing it on the skin where blisters appeared, or breathing it in as a vapor. (Not surprisingly, many people who underwent this type of “treatment” died of mercury poisoning.)

Other primitive treatments included using tinctures made of a flowering plant called guaiacum, as well as inducing “sweat baths” to eliminate the syphilitic toxins. In 1910, an arsenic-based drug called Salvarsan hit the market and was hailed as a “magic bullet” for its ability to target and destroy the syphilis-causing bacteria without harming the patient. However, while Salvarsan was effective in treating early-stage syphilis, it was largely ineffective by the time the infection progressed beyond the second stage. Tens of thousands of people each year continued to die of syphilis or were otherwise shipped off to psychiatric wards due to neurosyphilis.

It was in one of these psychiatric units in the early 20th century that Dr. Julius Wagner-Juaregg got the idea for a potential cure.

Wagner-Juaregg was an Austrian-born physician trained in “experimental pathology” at the University of Vienna. Wagner-Juaregg started his medical career conducting lab experiments on animals and then moved on to work at different psychiatric clinics in Vienna, despite having no training in psychiatry or neurology.

Wagner-Juaregg’s work was controversial to say the least. At the time, medicine – particularly psychiatric medicine – did not have anywhere near the same rigorous ethical standards that doctors, researchers, and other scientists are bound to today. Wagner-Juaregg would devise wild theories about the cause of their psychiatric ailments and then perform experimental procedures in an attempt to cure them. (As just one example, Wagner-Juaregg would sterilize his adolescent male patients, thinking “excessive masturbation” was the cause of their schizophrenia.)

But sometimes these wild theories paid off. In 1883, during his residency, Wagner-Juaregg noted that a female patient with mental illness who had contracted a skin infection and suffered a high fever experienced a sudden (and seemingly miraculous) remission from her psychosis symptoms after the fever had cleared. Wagner-Juaregg theorized that inducing a high fever in his patients with neurosyphilis could help them recover as well.

Eventually, Wagner-Juaregg was able to put his theory to the test. Around 1890, Wagner-Juaregg got his hands on something called tuberculin, a therapeutic treatment created by the German microbiologist Robert Koch in order to cure tuberculosis. Tuberculin would later turn out to be completely ineffective for treating tuberculosis, often creating severe immune responses in patients – but for a short time, Wagner-Juaregg had some success in using tuberculin to help his dementia patients. Giving his patients tuberculin resulted in a high fever – and after completing the treatment, Wagner-Jauregg reported that his patient’s dementia was completely halted. The success was short-lived, however: Wagner-Juaregg eventually had to discontinue tuberculin as a treatment, as it began to be considered too toxic.

By 1917, Wagner-Juaregg’s theory about syphilis and fevers was becoming more credible – and one day a new opportunity presented itself when a wounded soldier, stricken with malaria and a related fever, was accidentally admitted to his psychiatric unit.

When his findings were published in 1918, Wagner-Juaregg’s so-called “fever therapy” swept the globe.

What Wagner-Juaregg did next was ethically deplorable by any standard: Before he allowed the soldier any quinine (the standard treatment for malaria at the time), Wagner-Juaregg took a small sample of the soldier’s blood and inoculated three syphilis patients with the sample, rubbing the blood on their open syphilitic blisters.

It’s unclear how well the malaria treatment worked for those three specific patients – but Wagner-Juaregg’s records show that in the span of one year, he inoculated a total of nine patients with malaria, for the sole purpose of inducing fevers, and six of them made a full recovery. Wagner-Juaregg’s treatment was so successful, in fact, that one of his inoculated patients, an actor who was unable to work due to his dementia, was eventually able to find work again and return to the stage. Two additional patients – a military officer and a clerk – recovered from their once-terminal illnesses and returned to their former careers as well.

When his findings were published in 1918, Wagner-Juaregg’s so-called “fever therapy” swept the globe. The treatment was hailed as a breakthrough – but it still had risks. Malaria itself had a mortality rate of about 15 percent at the time. Many people considered that to be a gamble worth taking, compared to dying a painful, protracted death from syphilis.

Malaria could also be effectively treated much of the time with quinine, whereas other fever-causing illnesses were not so easily treated. Triggering a fever by way of malaria specifically, therefore, became the standard of care.

Tens of thousands of people with syphilitic dementia would go on to be treated with fever therapy until the early 1940s, when a combination of Salvarsan and penicillin caused syphilis infections to decline. Eventually, neurosyphilis became rare, and then nearly unheard of.

Despite his contributions to medicine, it’s important to note that Wagner-Juaregg was most definitely not a person to idolize. In fact, he was an outspoken anti-Semite and proponent of eugenics, arguing that Jews were more prone to mental illness and that people who were mentally ill should be forcibly sterilized. (Wagner-Juaregg later became a Nazi sympathizer during Hitler’s rise to power even though, bizarrely, his first wife was Jewish.) Another problematic issue was that his fever therapy involved experimental treatments on many who, due to their cognitive issues, could not give informed consent.

Lack of consent was also a fundamental problem with the syphilis study at Tuskegee, appalling research that began just 14 years after Wagner-Juaregg published his “fever therapy” findings.

Still, despite his outrageous views, Wagner-Juaregg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 1927 – and despite some egregious human rights abuses, the miraculous “fever therapy” was partly responsible for taming one of the deadliest plagues in human history.

Vaccines Without Vaccinations Won’t End the Pandemic

In this 2020 photograph, a bandage is placed on a patient who has just received a vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccine development has advanced at a record-setting pace, thanks to our nation's longstanding support for basic vaccine science coupled with massive public and private sector investments.

Yet, policymakers aren't according anywhere near the same level of priority to investments in the social, behavioral, and data science needed to better understand who and what influences vaccination decision-making. "If we want to be sure vaccines become vaccinations, this is exactly the kind of work that's urgently needed," says Dr. Bruce Gellin, President of Global Immunization at the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

Simply put: it's possible vaccines will remain in refrigerators and not be delivered to the arms of rolled-up sleeves if we don't quickly ramp up vaccine confidence research and broadly disseminate the findings.

According to the most recent Gallup poll, the share of U.S. adults who say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine rose to 58 percent this month from 50 percent in September, with non-white Americans and those ages 45-65 even less willing to be vaccinated. While there is still much we don't understand about COVID-19, we do know that without high levels of immunity in the population, a return to some semblance of normalcy is wishful thinking.

Research from prior vaccination campaigns such as H1N1, HPV, and the annual flu points us in the right direction. Key components of successful vaccination efforts require 1) Identifying the concerns of particular segments of the population; 2) Tailoring messages and incentives to address those concerns, and 3) Reaching out through trusted sources – health care providers, public health departments, and others in the community.

Research during the H1N1 flu found preparing people for some uncertainty actually improved trust, according to Dr. Sandra Crouse Quinn, professor and chair, Family Science, University of Maryland. Dr. Crouse Quinn's research during that period also underscored the need to address the specific vaccine concerns of racial and ethnic groups.

The stunning scientific achievement of COVID-19 vaccines anticipated to be ready in record time needs to be backed up by an equally ambitious and evidence-based effort to build the public's confidence in the vaccines.

Data science has provided crucial insight about the social media universe. Dr. Neil Johnson, a scientist at George Washington University, found that despite having fewer followers, anti-vaccination pages are more numerous and growing faster than pro-vaccination pages. They are more often linked to in discussions on other Facebook pages – such as school parent associations – where people are undecided about vaccination.

We've learned about building vaccine confidence from earlier campaigns. Now, however, we are faced with a unique and challenging set of obstacles to unpack quickly: How do we communicate the importance of eventual COVID-19 vaccines to Americans in light of the muddled-to-poor messaging from political leaders, the weaponizing of relatively simple public health recommendations, the enormous disproportionate toll on people of color, and the torrent of online misinformation? We urgently need data reflective of today's circumstances along with the policy to ensure it is quickly and effectively disseminated to the public health and clinical workforce.

Last year prompted in part by the measles outbreaks, Reps. Michael C. Burgess (R-TX) and Kim Shrier (D-WA), both physicians, introduced the bipartisan Vaccines Act to develop a national surveillance system to monitor vaccination rates and conduct a national campaign to increase awareness of the importance of vaccines. Unfortunately, that legislation wasn't passed. In response to COVID-19, Senate HELP Committee Ranking member Patty Murray (D-WA) has sought funds to strengthen vaccine confidence and combat misinformation with federally supported communication, research, and outreach efforts. Leading experts outside of Congress have called for this type of research, including the Sabin-Aspen Vaccine Science Policy Institute. Most recently, the National Academy of Sciences, in its report regarding the equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine, included as one of its recommendations the need for "a rapid-response program to advance the science behind vaccine confidence."

Addressing trust in vaccination has never been as challenging nor as consequential. The stunning scientific achievement of COVID-19 vaccines anticipated to be ready in record time needs to be backed up by an equally ambitious and evidence-based effort to build the public's confidence in the vaccines. In its remaining days, the Trump Administration should invest in building vaccine confidence with current resources, targeting efforts to ensure COVID vaccines reduce rather than exacerbate racial and ethnic health disparities. Congress must also act to provide the additional research and outreach resources needed as well as pass the Vaccines Act so we are better prepared in the future.

If we don't succeed, COVID-19 will continue wreaking havoc on our health, our society, and our economy. We will also permanently jeopardize public trust in vaccines – one of the most successful medical interventions in human history.

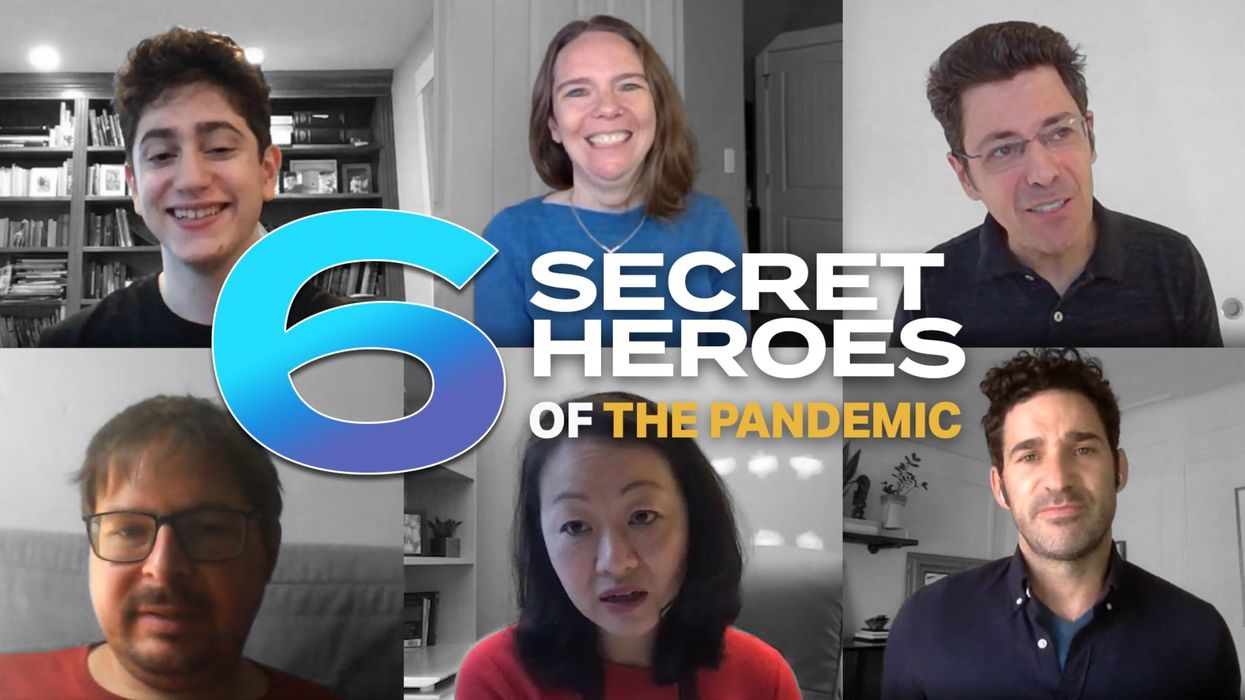

New Video: Secret Heroes of the Pandemic

These 6 people deserve to be widely known and celebrated for their brave and ingenious contributions to battling the pandemic.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.