Trading syphilis for malaria: How doctors treated one deadly disease by infecting patients with another

In the 1920s, doctors induced a high fever in patients - so called "fever therapy" - as a way to help them recover from syphilis, though it involved ethical problems.

If you had lived one hundred years ago, syphilis – a bacterial infection spread by sexual contact – would likely have been one of your worst nightmares. Even though syphilis still exists, it can now be detected early and cured quickly with a course of antibiotics. Back then, however, before antibiotics and without an easy way to detect the disease, syphilis was very often a death sentence.

To understand how feared syphilis once was, it’s important to understand exactly what it does if it’s allowed to progress: the infections start off as small, painless sores or even a single sore near the vagina, penis, anus, or mouth. The sores disappear around three to six weeks after the initial infection – but untreated, syphilis moves into a secondary stage, often presenting as a mild rash in various areas of the body (such as the palms of a person’s hands) or through other minor symptoms. The disease progresses from there, often quietly and without noticeable symptoms, sometimes for decades before it reaches its final stages, where it can cause blindness, organ damage, and even dementia. Research indicates, in fact, that as much as 10 percent of psychiatric admissions in the early 20th century were due to dementia caused by syphilis, also known as neurosyphilis.

Like any bacterial disease, syphilis can affect kids, too. Though it’s spread primarily through sexual contact, it can also be transmitted from mother to child during birth, causing lifelong disability.

The poet-physician Aldabert Bettman, who wrote fictionalized poems based on his experiences as a doctor in the 1930s, described the effect syphilis could have on an infant in his poem Daniel Healy:

I always got away clean

when I went out

With the boys.

The night before

I was married

I went out,—But was not so fortunate;

And I infected

My bride.

When little Daniel

Was born

His eyes discharged;

And I dared not tell

That because

I had seen too much

Little Daniel sees not at all

Given the horrors of untreated syphilis, it’s maybe not surprising that people would go to extremes to try and treat it. One of the earliest remedies for syphilis, dating back to 15th century Naples, was using mercury – either rubbing it on the skin where blisters appeared, or breathing it in as a vapor. (Not surprisingly, many people who underwent this type of “treatment” died of mercury poisoning.)

Other primitive treatments included using tinctures made of a flowering plant called guaiacum, as well as inducing “sweat baths” to eliminate the syphilitic toxins. In 1910, an arsenic-based drug called Salvarsan hit the market and was hailed as a “magic bullet” for its ability to target and destroy the syphilis-causing bacteria without harming the patient. However, while Salvarsan was effective in treating early-stage syphilis, it was largely ineffective by the time the infection progressed beyond the second stage. Tens of thousands of people each year continued to die of syphilis or were otherwise shipped off to psychiatric wards due to neurosyphilis.

It was in one of these psychiatric units in the early 20th century that Dr. Julius Wagner-Juaregg got the idea for a potential cure.

Wagner-Juaregg was an Austrian-born physician trained in “experimental pathology” at the University of Vienna. Wagner-Juaregg started his medical career conducting lab experiments on animals and then moved on to work at different psychiatric clinics in Vienna, despite having no training in psychiatry or neurology.

Wagner-Juaregg’s work was controversial to say the least. At the time, medicine – particularly psychiatric medicine – did not have anywhere near the same rigorous ethical standards that doctors, researchers, and other scientists are bound to today. Wagner-Juaregg would devise wild theories about the cause of their psychiatric ailments and then perform experimental procedures in an attempt to cure them. (As just one example, Wagner-Juaregg would sterilize his adolescent male patients, thinking “excessive masturbation” was the cause of their schizophrenia.)

But sometimes these wild theories paid off. In 1883, during his residency, Wagner-Juaregg noted that a female patient with mental illness who had contracted a skin infection and suffered a high fever experienced a sudden (and seemingly miraculous) remission from her psychosis symptoms after the fever had cleared. Wagner-Juaregg theorized that inducing a high fever in his patients with neurosyphilis could help them recover as well.

Eventually, Wagner-Juaregg was able to put his theory to the test. Around 1890, Wagner-Juaregg got his hands on something called tuberculin, a therapeutic treatment created by the German microbiologist Robert Koch in order to cure tuberculosis. Tuberculin would later turn out to be completely ineffective for treating tuberculosis, often creating severe immune responses in patients – but for a short time, Wagner-Juaregg had some success in using tuberculin to help his dementia patients. Giving his patients tuberculin resulted in a high fever – and after completing the treatment, Wagner-Jauregg reported that his patient’s dementia was completely halted. The success was short-lived, however: Wagner-Juaregg eventually had to discontinue tuberculin as a treatment, as it began to be considered too toxic.

By 1917, Wagner-Juaregg’s theory about syphilis and fevers was becoming more credible – and one day a new opportunity presented itself when a wounded soldier, stricken with malaria and a related fever, was accidentally admitted to his psychiatric unit.

When his findings were published in 1918, Wagner-Juaregg’s so-called “fever therapy” swept the globe.

What Wagner-Juaregg did next was ethically deplorable by any standard: Before he allowed the soldier any quinine (the standard treatment for malaria at the time), Wagner-Juaregg took a small sample of the soldier’s blood and inoculated three syphilis patients with the sample, rubbing the blood on their open syphilitic blisters.

It’s unclear how well the malaria treatment worked for those three specific patients – but Wagner-Juaregg’s records show that in the span of one year, he inoculated a total of nine patients with malaria, for the sole purpose of inducing fevers, and six of them made a full recovery. Wagner-Juaregg’s treatment was so successful, in fact, that one of his inoculated patients, an actor who was unable to work due to his dementia, was eventually able to find work again and return to the stage. Two additional patients – a military officer and a clerk – recovered from their once-terminal illnesses and returned to their former careers as well.

When his findings were published in 1918, Wagner-Juaregg’s so-called “fever therapy” swept the globe. The treatment was hailed as a breakthrough – but it still had risks. Malaria itself had a mortality rate of about 15 percent at the time. Many people considered that to be a gamble worth taking, compared to dying a painful, protracted death from syphilis.

Malaria could also be effectively treated much of the time with quinine, whereas other fever-causing illnesses were not so easily treated. Triggering a fever by way of malaria specifically, therefore, became the standard of care.

Tens of thousands of people with syphilitic dementia would go on to be treated with fever therapy until the early 1940s, when a combination of Salvarsan and penicillin caused syphilis infections to decline. Eventually, neurosyphilis became rare, and then nearly unheard of.

Despite his contributions to medicine, it’s important to note that Wagner-Juaregg was most definitely not a person to idolize. In fact, he was an outspoken anti-Semite and proponent of eugenics, arguing that Jews were more prone to mental illness and that people who were mentally ill should be forcibly sterilized. (Wagner-Juaregg later became a Nazi sympathizer during Hitler’s rise to power even though, bizarrely, his first wife was Jewish.) Another problematic issue was that his fever therapy involved experimental treatments on many who, due to their cognitive issues, could not give informed consent.

Lack of consent was also a fundamental problem with the syphilis study at Tuskegee, appalling research that began just 14 years after Wagner-Juaregg published his “fever therapy” findings.

Still, despite his outrageous views, Wagner-Juaregg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 1927 – and despite some egregious human rights abuses, the miraculous “fever therapy” was partly responsible for taming one of the deadliest plagues in human history.

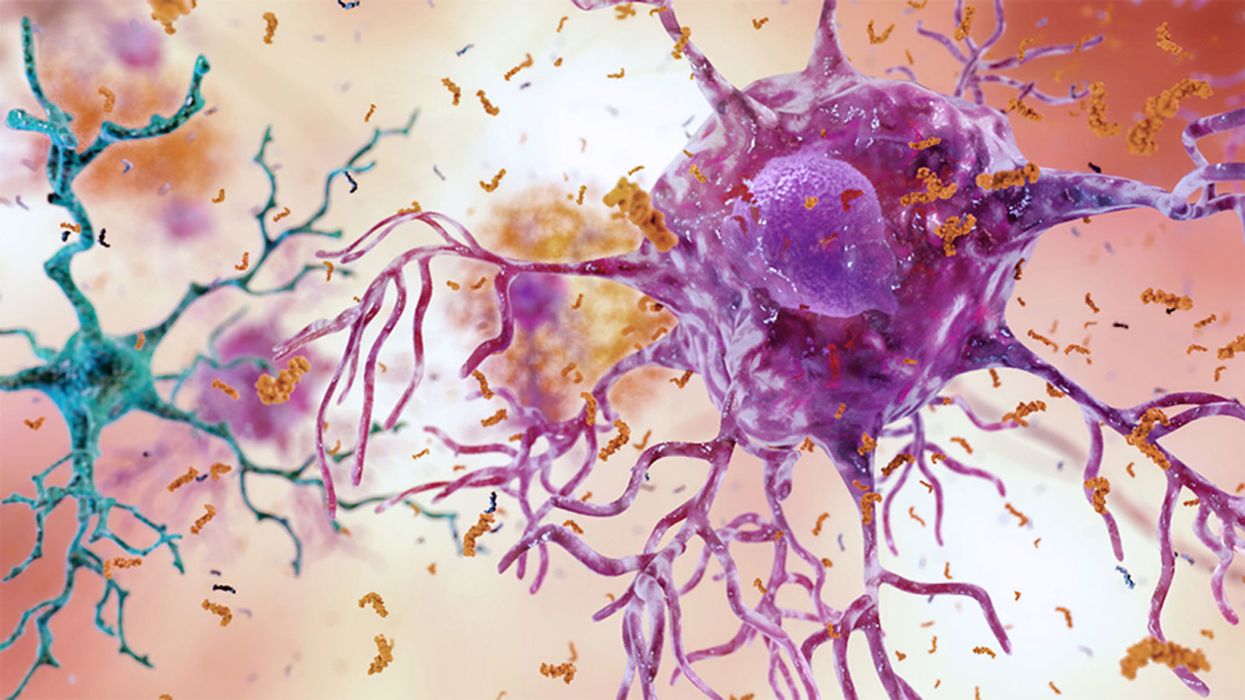

A Mother-and-Daughter Team Have Developed What May Be the World’s First Alzheimer’s Vaccine

Brain inflammation from Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's is a terrible disease that robs a person of their personality and memory before eventually leading to death. It's the sixth-largest killer in the U.S. and, currently, there are 5.8 million Americans living with the disease.

Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

It devastates people and families and it's estimated that Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia will cost the U.S. $290 billion dollars this year alone. It's estimated that it will become a trillion-dollar-a-year disease by 2050.

There have been over 200 unsuccessful attempts to find a cure for the disease and the clinical trial termination rate is 98 percent.

Alzheimer's is caused by plaque deposits that develop in brain tissue that become toxic to brain cells. One of the major hurdles to finding a cure for the disease is that it's impossible to clear out the deposits from the tissue. So scientists have turned their attention to early detection and prevention.

One very encouraging development has come out of the work done by Dr. Chang Yi Wang, PhD. Wang is a prolific bio-inventor; one of her biggest successes is developing a foot-and-mouth vaccine for pigs that has been administered more than three billion times.

Mei Mei Hu

Brainstorm Health / Flickr.

In January, United Neuroscience, a biotech company founded by Yi, her daughter Mei Mei Hu, and son-in-law, Louis Reese, announced the first results from a phase IIa clinical trial on UB-311, an Alzheimer's vaccine.

The vaccine has synthetic versions of amino acid chains that trigger antibodies to attack Alzheimer's protein the blood. Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

"We were able to generate some antibodies in all patients, which is unusual for vaccines," Yi told Wired. "We're talking about almost a 100 percent response rate. So far, we have seen an improvement in three out of three measurements of cognitive performance for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease."

The researchers also claim it can delay the onset of the disease by five years. While this would be a godsend for people with the disease and their families, according to Elle, it could also save Medicare and Medicaid more than $220 billion.

"You'd want to see larger numbers, but this looks like a beneficial treatment," James Brown, director of the Aston University Research Centre for Healthy Ageing, told Wired. "This looks like a silver bullet that can arrest or improve symptoms and, if it passes the next phase, it could be the best chance we've got."

"A word of caution is that it's a small study," says Drew Holzapfel, acting president of the nonprofit UsAgainstAlzheimer's, said according to Elle. "But the initial data is compelling."

The company is now working on its next clinical trial of the vaccine and while hopes are high, so is the pressure. The company has already invested $100 million developing its vaccine platform. According to Reese, the company's ultimate goal is to create a host of vaccines that will be administered to protect people from chronic illness.

"We have a 50-year vision -- to immuno-sculpt people against chronic illness and chronic aging with vaccines as prolific as vaccines for infectious diseases," he told Elle.

[Editor's Note: This article was originally published by Upworthy here and has been republished with permission.]

Turning Algae Into Environmentally Friendly Fuel Just Got Faster and Smarter

Algae in the Mediterranean sea.

Was your favorite beach closed this summer? Algae blooms are becoming increasingly the reason to blame and, as the climate heats up, scientists say we can expect more of the warm water-loving blue-green algae to grow.

"We have removed a significant development barrier to make algal biofuel production more efficient and smarter."

Oddly enough, the pesky growth could help fuel our carbon-friendly options.

This year, the University of Utah scientists discovered a faster way to turn algae into fuel. Algae is filled with lipids that we can feed our energy-hungry diesel engines. The problem is extracting the lipids, which usually requires more energy to transform than the actual energy we'd get – not achieving what scientists call "energy parity."

But now, the University of Utah team has discovered a new mix that is more efficient and much faster. We can now extract more power from algae with less waste materials after the fact. Paper co-author Dr. Leonard Pease says, "We have removed a significant development barrier to make algal biofuel production more efficient and smarter. Our method puts us much closer to creating biofuels energy parity than we were before."

Next Up

Algae has a lot going for it as an alternative fuel source. It grows fast and easily, absorbs carbon dioxide, does not compete with food crops for land, and could produce up to 60 times more oil than standard land-based energy crops, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Yet the costs of algal biofuel production are still expensive for now.

According to Science Daily, only about five percent of total primary energy use in the United States came from algae and other biomass forms. By making the process more efficient, America and other nations could potentially begin relying on more plentiful resources – which, ironically, are more common now because of climate change.

Algae fuel efficiency is already a proven concept. A decade ago, Continental Airlines completed a 90-minute Boeing 737-800 flight with one engine split between biofuel and aircraft fuel. The biofuel was straight from algae. (Other flights were done based on nut fuel and other alternative sources.) The commercial airplane required no modification to the engine and the biofuel itself exceeded the standards of traditional jet fuel.

The problem, as noted at the time, is that biofuels derived from algae had yet to be proven as "commercially competitive."

The University of Utah's discovery could mean cheaper processing. At this point, it is less about if it works and more about if it is a practical alternative.

However, it's unclear how long it will take for algae to become more mainstream, if ever.

Open Questions

Higher efficiency and simpler transformations could mean lower prices and more business access. However, it's unclear how long it will take for algae to become more mainstream, if ever. The algae biofuel worked great for a relatively sophisticated Boeing 737 engine, but your family car, the cross-country delivery trucks and other less powerful machines may need to be modified – and that means the industry-at-large would have to revise their products in order to support the change.

Future-focused groups are already looking at how algae can fuel our space programs, especially if it is more renewable, safe and, potentially, cheaper than our traditional fuel choices. But first, it is worth waiting and seeing if corporations and, later, citizens are willing to take the plunge.