Tiny, tough “water bears” may help bring new vaccines and medicines to sub-Saharan Africa

Tardigrades can completely dehydrate and later rehydrate themselves, a survival trick that scientists are harnessing to preserve medicines in hot temperatures.

Microscopic tardigrades, widely considered to be some of the toughest animals on earth, can survive for decades without oxygen or water and are thought to have lived through a crash-landing on the moon. Also known as water bears, they survive by fully dehydrating and later rehydrating themselves – a feat only a few animals can accomplish. Now scientists are harnessing tardigrades’ talents to make medicines that can be dried and stored at ambient temperatures and later rehydrated for use—instead of being kept refrigerated or frozen.

Many biologics—pharmaceutical products made by using living cells or synthesized from biological sources—require refrigeration, which isn’t always available in many remote locales or places with unreliable electricity. These products include mRNA and other vaccines, monoclonal antibodies and immuno-therapies for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions. Cooling is also needed for medicines for blood clotting disorders like hemophilia and for trauma patients.

Formulating biologics to withstand drying and hot temperatures has been the holy grail for pharmaceutical researchers for decades. It’s a hard feat to manage. “Biologic pharmaceuticals are highly efficacious, but many are inherently unstable,” says Thomas Boothby, assistant professor of molecular biology at University of Wyoming. Therefore, during storage and shipping, they must be refrigerated at 2 to 8 degrees Celsius (35 to 46 degrees Fahrenheit). Some must be frozen, typically at -20 degrees Celsius, but sometimes as low -90 degrees Celsius as was the case with the Pfizer Covid vaccine.

For Covid, fewer than 73 percent of the global population received even one dose. The need for refrigerated or frozen handling was partially to blame.

The costly cold chain

The logistics network that ensures those temperature requirements are met from production to administration is called the cold chain. This cold chain network is often unreliable or entirely lacking in remote, rural areas in developing nations that have malfunctioning electrical grids. “Almost all routine vaccines require a cold chain,” says Christopher Fox, senior vice president of formulations at the Access to Advanced Health Institute. But when the power goes out, so does refrigeration, putting refrigerated or frozen medical products at risk. Consequently, the mRNA vaccines developed for Covid-19 and other conditions, as well as more traditional vaccines for cholera, tetanus and other diseases, often can’t be delivered to the most remote parts of the world.

To understand the scope of the challenge, consider this: In the U.S., more than 984 million doses of Covid-19 vaccine have been distributed so far. Each one needed refrigeration that, even in the U.S., proved challenging. Now extrapolate to all vaccines and the entire world. For Covid, fewer than 73 percent of the global population received even one dose. The need for refrigerated or frozen handling was partially to blame.

Globally, the cold chain packaging market is valued at over $15 billion and is expected to exceed $60 billion by 2033.

Adobe Stock

Freeze-drying, also called lyophilization, which is common for many vaccines, isn’t always an option. Many freeze-dried vaccines still need refrigeration, and even medicines approved for storage at ambient temperatures break down in the heat of sub-Saharan Africa. “Even in a freeze-dried state, biologics often will undergo partial rehydration and dehydration, which can be extremely damaging,” Boothby explains.

The cold chain is also very expensive to maintain. The global pharmaceutical cold chain packaging market is valued at more than $15 billion, and is expected to exceed $60 billion by 2033, according to a report by Future Market Insights. This cost is only expected to grow. According to the consulting company Accenture, the number of medicines that require the cold chain are expected to grow by 48 percent, compared to only 21 percent for non-cold-chain therapies.

Tardigrades to the rescue

Tardigrades are only about a millimeter long – with four legs and claws, and they lumber around like bears, thus their nickname – but could provide a big solution. “Tardigrades are unique in the animal kingdom, in that they’re able to survive a vast array of environmental insults,” says Boothby, the Wyoming professor. “They can be dried out, frozen, heated past the boiling point of water and irradiated at levels that are thousands of times more than you or I could survive.” So, his team is gradually unlocking tardigrades’ survival secrets and applying them to biologic pharmaceuticals to make them withstand both extreme heat and desiccation without losing efficacy.

Boothby’s team is focusing on blood clotting factor VIII, which, as the name implies, causes blood to clot. Currently, Boothby is concentrating on the so-called cytoplasmic abundant heat soluble (CAHS) protein family, which is found only in tardigrades, protecting them when they dry out. “We showed we can desiccate a biologic (blood clotting factor VIII, a key clotting component) in the presence of tardigrade proteins,” he says—without losing any of its effectiveness.

The researchers mixed the tardigrade protein with the blood clotting factor and then dried and rehydrated that substance six times without damaging the latter. This suggests that biologics protected with tardigrade proteins can withstand real-world fluctuations in humidity.

Furthermore, Boothby’s team found that when the blood clotting factor was dried and stabilized with tardigrade proteins, it retained its efficacy at temperatures as high as 95 degrees Celsius. That’s over 200 degrees Fahrenheit, much hotter than the 58 degrees Celsius that the World Meteorological Organization lists as the hottest recorded air temperature on earth. In contrast, without the protein, the blood clotting factor degraded significantly. The team published their findings in the journal Nature in March.

Although tardigrades rarely live more than 2.5 years, they have survived in a desiccated state for up to two decades, according to Animal Diversity Web. This suggests that tardigrades’ CAHS protein can protect biologic pharmaceuticals nearly indefinitely without refrigeration or freezing, which makes it significantly easier to deliver them in locations where refrigeration is unreliable or doesn’t exist.

The tricks of the tardigrades

Besides the CAHS proteins, tardigrades rely on a type of sugar called trehalose and some other protectants. So, rather than drying up, their cells solidify into rigid, glass-like structures. As that happens, viscosity between cells increases, thereby slowing their biological functions so much that they all but stop.

Now Boothby is combining CAHS D, one of the proteins in the CAHS family, with trehalose. He found that CAHS D and trehalose each protected proteins through repeated drying and rehydrating cycles. They also work synergistically, which means that together they might stabilize biologics under a variety of dry storage conditions.

“We’re finding the protective effect is not just additive but actually is synergistic,” he says. “We’re keen to see if something like that also holds true with different protein combinations.” If so, combinations could possibly protect against a variety of conditions.

Commercialization outlook

Before any stabilization technology for biologics can be commercialized, it first must be approved by the appropriate regulators. In the U.S., that’s the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Developing a new formulation would require clinical testing and vast numbers of participants. So existing vaccines and biologics likely won’t be re-formulated for dry storage. “Many were developed decades ago,” says Fox. “They‘re not going to be reformulated into thermo-stable vaccines overnight,” if ever, he predicts.

Extending stability outside the cold chain, even for a few days, can have profound health, environmental and economic benefits.

Instead, this technology is most likely to be used for the new products and formulations that are just being created. New and improved vaccines will be the first to benefit. Good candidates include the plethora of mRNA vaccines, as well as biologic pharmaceuticals for neglected diseases that affect parts of the world where reliable cold chain is difficult to maintain, Boothby says. Some examples include new, more effective vaccines for malaria and for pathogenic Escherichia coli, which causes diarrhea.

Tallying up the benefits

Extending stability outside the cold chain, even for a few days, can have profound health, environmental and economic benefits. For instance, MenAfriVac, a meningitis vaccine (without tardigrade proteins) developed for sub-Saharan Africa, can be stored at up to 40 degrees Celsius for four days before administration. “If you have a few days where you don’t need to maintain the cold chain, it’s easier to transport vaccines to remote areas,” Fox says, where refrigeration does not exist or is not reliable.

Better health is an obvious benefit. MenAfriVac reduced suspected meningitis cases by 57 percent in the overall population and more than 99 percent among vaccinated individuals.

Lower healthcare costs are another benefit. One study done in Togo found that the cold chain-related costs increased the per dose vaccine price up to 11-fold. The ability to ship the vaccines using the usual cold chain, but transporting them at ambient temperatures for the final few days cut the cost in half.

There are environmental benefits, too, such as reducing fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Cold chain transports consume 20 percent more fuel than non-cold chain shipping, due to refrigeration equipment, according to the International Trade Administration.

A study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University compared the greenhouse gas emissions of the new, oral Vaxart COVID-19 vaccine (which doesn’t require refrigeration) with four intramuscular vaccines (which require refrigeration or freezing). While the Vaxart vaccine is still in clinical trials, the study found that “up to 82.25 million kilograms of CO2 could be averted by using oral vaccines in the U.S. alone.” That is akin to taking 17,700 vehicles out of service for one year.

Although tardigrades’ protective proteins won’t be a component of biologic pharmaceutics for several years, scientists are proving that this approach is viable. They are hopeful that a day will come when vaccines and biologics can be delivered anywhere in the world without needing refrigerators or freezers en route.

For Kids with Progeria, New Therapies May Offer Revolutionary Hope for a Longer Life

Sammy Basso is one of around 400 young people in the world with progeria.

Sammy Basso has some profound ideas about fate. As long as he has been alive, he has known he has minimal control over his own. His parents, however, had to transition from a world of unlimited possibility to one in which their son might not live to his 20s.

"I remember very clearly that day because Sammy was three years old," his mother says of the day a genetic counselor diagnosed Sammy with progeria. "It was a devastating day for me."

But to Sammy, he has always been himself: a smart kid, interested in science, a little smaller than his classmates, with one notable kink in his DNA. In one copy of the gene that codes for the protein Lamin A, Sammy has a T where there should be a C. The incorrect code creates a toxic protein called progerin, which destabilizes Sammy's cells and makes him age much faster than a person who doesn't have the mutation. The older he gets, the more he is in danger of strokes, heart failure, or a heart attack. "I am okay with my situation," he says from his home in Tezze sul Brenta, Italy. "But I think, yes, fate has a great role in my life."

Just 400 or so people in the world live with progeria: The mutation that causes it usually arises de novo, or "of new," meaning that it is not inherited but happens spontaneously during gestation. The challenge, as with all rare diseases, is that few cases means few treatments.

"When we first started, there was absolutely nothing out there," says Leslie Gordon, a physician-researcher who co-founded the Progeria Research Foundation in 1999 after her own son, also named Sam, was diagnosed with the disease. "We knew we had to jumpstart the entire field, so we collected money through road races and special events and writing grants and all sorts of donors… I think the first year we raised $75,000, most of it from one donor."

"We have not only the possibility but the responsibility to make the world a better world, and also to make a body a better body."

By 2003, the foundation had collaborated with Francis Collins, a geneticist who is now director of the National Institutes of Health, to work out the genetic basis for progeria—that single mutation Sammy has. The discovery led to interest in lonafarnib, a drug that was already being used in cancer patients but could potentially operate downstream of the mutation, preventing the buildup of the defective progerin in the body. "We funded cellular studies to look at a lonafarnib in cells, mouse studies to look at lonafarnib in mouse models of progeria… and then we initiated the clinical trials," Gordon says.

Sammy Basso's family had gotten involved with the Progeria Research Foundation through their international patient registry, which maintains relationships with families in 49 countries. "We started to hear about lonafarnib in 2006 from Leslie Gordon," says Sammy's father, Amerigo Basso, with his son translating. "She told us about the lonafarnib. And we were very happy because for the first time we understood that there was something that could help our son and our lives." Amerigo used the Italian word speranza, which means hope.

Still, Sammy wasn't sure if lonafarnib was right for him. "Since when I was very young I thought that everything happens for a reason. So, in my mind, if God made me with progeria, there was a reason, and to try to heal from progeria was something wrong," he says. Gradually, his parents and doctors, and Leslie Gordon, convinced him otherwise. Sammy began to believe that God was also the force behind doctors, science, and research. "And so we have not only the possibility but the responsibility to make the world a better world, and also to make a body a better body," he says.

Sammy Basso and his parents.

Courtesy of Basso

Sammy began taking lonafarnib, with the Progeria Research Foundation intermittently flying him, and other international trial participants, to Boston for tests. He was immediately beset by some of the drug's more unpleasant side effects: Stomach problems, nausea, and vomiting. "The first period was absolutely the worst period of my life," he says.

At first, doctors prescribed other medicines for the side effects, but to Sammy it had as much effect as drinking water. He visited doctor after doctor, with some calling him weekly or even daily to ask how he was doing. Eventually the specialists decided that he should lower his dose, balancing his pain with the benefit of the drug. Sammy can't actually feel any positive effect of the lonafarnib, but his health measurements have improved relative to people with progeria who don't take it.

While they never completely disappeared, Sammy's side effects decreased to the point that he could live. Inspired by the research that led to lonafarnib, he went to university to study molecular biology. For his thesis work, he travelled to Spain to perform experiments on cells and on mice with progeria, learning how to use the gene-editing technique CRISPR-Cas9 to cut out the mutated bit of DNA. "I was so excited to participate in this study," Sammy says. He felt like his work could make a difference.

In 2018, the Progeria Research Foundation was hosting one of their biennial workshops when Francis Collins, the researcher who had located the mutation behind progeria 15 years earlier, got in touch with Leslie Gordon. "Francis called me and said, Hey, I just saw a talk by David Liu from the Broad [Institute]. And it was pretty amazing. He has been looking at progeria and has very early, but very exciting data… Do you have any spaces, any slots you could make in your program for late breaking news?"

Gordon found a spot, and David Liu came to talk about what was going on in his lab, which was an even more advanced treatment that led to mice with the progeria mutation living into their senior mouse years—substantially closer to a normal lifespan. Liu's lab had built on the idea of CRISPR-Cas9 to create a more elegant genetic process called base editing: Instead of chopping out mutated DNA, a scientist could chemically convert an incorrect DNA letter to the correct one, like the search and replace function in word processing software. Mice who had their Lamin-A mutations corrected this way lived more than twice as long as untreated animals.

Sammy was in the audience at Dr. Liu's talk. "When I heard about this base editing as a younger scientist, I thought that I was living in the future," he says. "When my parents had my diagnosis of progeria, the science knew very little information about DNA. And now we are talking about healing the DNA… It is incredible."

Lonafarnib (also called Zokinvy) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration this past November. Sammy, now 25, still takes it, and still manages his side effects. With luck, the gift of a few extra years will act as a bridge until he can try Liu's revolutionary new gene treatment, which has not yet begun testing in humans. While Leslie Gordon warns that she's always wrong about things like this, she hopes to see the new base editing techniques in clinical trials in the next year or two. Sammy won't need to be convinced to try it this time; his thinking on fate has evolved since his first encounter with lonafarnib.

"I would be very happy to try it," he says. "I know that for a non-scientist it can be difficult to understand. Some people think that we are the DNA. We are not. The DNA is a part of us, and to correct it is to do what we are already doing—just better." In short, a gene therapy, while it may seem like science fiction, is no different from a pill. For Sammy, both are a new way to think about fate: No longer something that simply happens to him.

Want to Motivate Vaccinations? Message Optimism, Not Doom

There is a lot to be optimistic about regarding the new safe and highly effective vaccines, which are moving society closer toward the goal of close human contact once again.

After COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, life as we knew it altered dramatically and millions went into lockdown. Since then, most of the world has had to contend with masks, distancing, ventilation and cycles of lockdowns as surges flare up. Deaths from COVID-19 infection, along with economic and mental health effects from the shutdowns, have been devastating. The need for an ultimate solution -- safe and effective vaccines -- has been paramount.

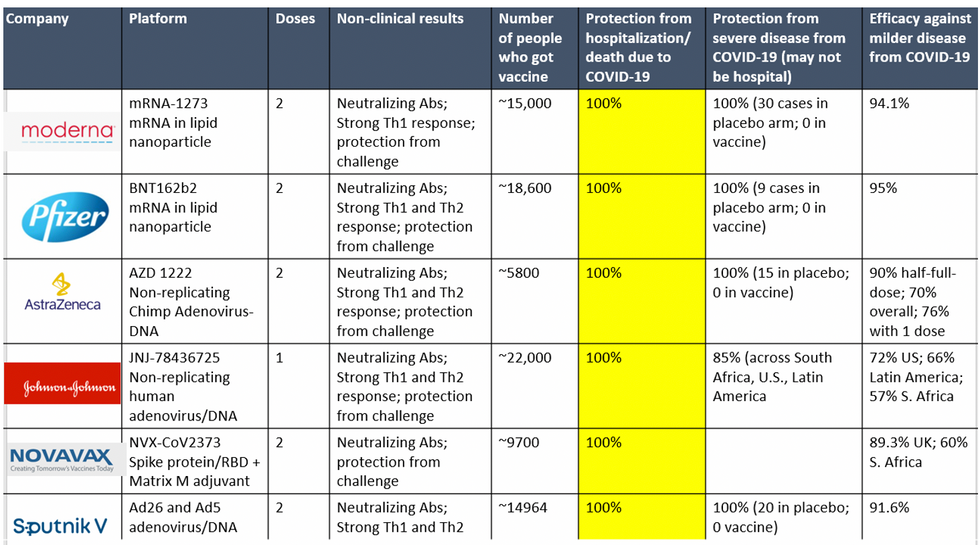

On November 9, 2020 (just 8 months after the pandemic announcement), the press release for the first effective COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech was issued, followed by positive announcements regarding the safety and efficacy of five other vaccines from Moderna, University of Oxford/AztraZeneca, Novavax, Johnson and Johnson and Sputnik V. The Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have earned emergency use authorization through the FDA in the United States and are being distributed. We -- after many long months -- are seeing control of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic glimmering into sight.

To be clear, these vaccine candidates for COVID-19, both authorized and not yet authorized, are highly effective and safe. In fact, across all trials and sites, all six vaccines were 100% effective in preventing hospitalizations and death from COVID-19.

All Vaccines' Phase 3 Clinical Data

Complete protection against hospitalization and death from COVID-19 exhibited by all vaccines with phase 3 clinical trial data.

This astounding level of protection from SARS-CoV-2 from all vaccine candidates across multiple regions is likely due to robust T cell response from vaccination and will "defang" the virus from the concerns that led to COVID-19 restrictions initially: the ability of the virus to cause severe illness. This is a time of hope and optimism. After the devastating third surge of COVID-19 infections and deaths over the winter, we finally have an opportunity to stem the crisis – if only people readily accept the vaccines.

Amidst these incredible scientific advancements, however, public health officials and politicians have been pushing downright discouraging messaging. The ubiquitous talk of ongoing masks and distancing restrictions without any clear end in sight threatens to dampen uptake of the vaccines. It's imperative that we break down each concern and see if we can revitalize our public health messaging accordingly.

The first concern: we currently do not know if the vaccines block asymptomatic infection as well as symptomatic disease, since none of the phase 3 vaccine trials were set up to answer this question. However, there is biological plausibility that the antibodies and T-cell responses blocking symptomatic disease will also block asymptomatic infection in the nasal passages. IgG immunoglobulins (generated and measured by the vaccine trials) enter the nasal mucosa and systemic vaccinations generate IgA antibodies at mucosal surfaces. Monoclonal antibodies given to outpatients with COVID-19 hasten viral clearance from the airways.

Although it is prudent for those who are vaccinated to wear masks around the unvaccinated in case a slight risk of transmission remains, two fully vaccinated people can comfortably abandon masking around each other.

Moreover, data from the AztraZeneca trial (including in the phase 3 trial final results manuscript), where weekly self-swabbing was done by participants, and data from the Moderna trial, where a nasal swab was performed prior to the second dose, both showed risk reductions in asymptomatic infection with even a single dose. Finally, real-world data from a large Pfizer-based vaccine campaign in Israel shows a 50% reduction in infections (asymptomatic or symptomatic) after just the first dose.

Therefore, the likelihood of these vaccines blocking asymptomatic carriage, as well as symptomatic disease, is high. Although it is prudent for those who are vaccinated to wear masks around the unvaccinated in case a slight risk of transmission remains, two fully vaccinated people can comfortably abandon masking around each other. Moreover, as the percentage of vaccinated people increases, it will be increasingly untenable to impose restrictions on this group. Once herd immunity is reached, these restrictions can and should be abandoned altogether.

The second concern translating to "doom and gloom" messaging lately is around the identification of troubling new variants due to enhanced surveillance via viral sequencing. Four major variants circulating at this point (with others described in the past) are the B.1.1.7 variant ("UK variant"), B.1.351 ("South Africa variant), P.1. ("Brazil variant"), and the L452R variant identified in California. Although the UK variant is likely to be more transmissible, as is the South Africa variant, we have no reason to believe that masks, distancing and ventilation are ineffective against these variants.

Moreover, neutralizing antibody titers with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines do not seem to be significantly reduced against the variants. Finally, although the Novavax 2-dose and Johnson and Johnson (J&J) 1-dose vaccines had lower rates of efficacy against moderate COVID-19 disease in South Africa, their efficacy against severe disease was impressively high. In fact J&J's vaccine still prevented 100% of hospitalizations and death from COVID-19. When combining both hospitalizations/deaths and severe symptoms managed at home, the J&J 1-dose vaccine was 85% protective across all three sites of the trial: the U.S., Latin America (including Brazil), and South Africa.

In South Africa, nearly all cases of COVID-19 (95%) were due to infection with the B.1.351 SARS-CoV-2 variant. Finally, since herd immunity does not rely on maximal immune responses among all individuals in a society, the Moderna/Pfizer/J&J vaccines are all likely to achieve that goal against variants. And thankfully, all of these vaccines can be easily modified to boost specifically against a new variant if needed (indeed, Moderna and Pfizer are already working on boosters against the prominent variants).

The third concern of some public health officials is that people will abandon all restrictions once vaccinated unless overly cautious messages are drilled into them. Indeed, the false idea that if you "give people an inch, they will take a mile" has been misinforming our messaging about mitigation since the beginning of the pandemic. For example, the very phrase "stay at home" with all of its non-applicability for essential workers and single individuals is stigmatizing and unrealistic for many. Instead, the message should have focused on how people can additively reduce their risks under different circumstances.

The public will be more inclined to trust health officials if those officials communicate with nuanced messages backed up by evidence, rather than with broad brushstrokes that shame. Therefore, we should be saying that "vaccinated people can be together with other vaccinated individuals without restrictions but must protect the unvaccinated with masks and distancing." And we can say "unvaccinated individuals should adhere to all current restrictions until vaccinated" without fear of misunderstandings. Indeed, this kind of layered advice has been communicated to people living with HIV and those without HIV for a long time (if you have HIV but partner does not, take these precautions; if both have HIV, you can do this, etc.).

Our heady progress in vaccine development, along with the incredible efficacy results of all of them, is unprecedented. However, we are at risk of undermining such progress if people balk at the vaccine because they don't believe it will make enough of a difference. One of the most critical messages we can deliver right now is that these vaccines will eventually free us from the restrictions of this pandemic. Let's use tiered messaging and clear communication to boost vaccine optimism and uptake, and get us to the goal of close human contact once again.