Technology’s Role in Feeding a Soaring Population Raises This Dilemma

When farmer Terry Wanzek walks out in his fields, he sometimes sees a grove of trees, which reminds him of his grandfather, who planted those trees. Or he looks out over the pond, which deer, ducks and pheasant use for water, and he knows that his grandfather made a decision to drain land and put the pond in that exact spot.

Growing more with fewer resources is becoming increasingly urgent as the Earth's population is expected to hit 9.1 billion by 2050.

"There is a connection that goes beyond running a business and making a profit," says Wanzek, a fourth-generation North Dakota farmer who raises spring wheat, corn, soybeans, barley, dry edible beans and sunflowers. "There is a connection to family, to your ancestors and there is a connection to your posterity and your kids."

Wanzek's corn and soybeans are genetically modified (GM) crops, which means that they have been altered at the DNA level to create desirable traits. This intervention, he says, allows him to start growing earlier and to produce more food per acre.

Growing more with fewer resources is becoming increasingly urgent as the Earth's population is expected to hit 9.1 billion by 2050, with nearly all of the rise coming from developing countries, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. This population will be urban, which means they'll likely be eating fewer grains and other staple crops, and more vegetables, fruits, meat, dairy, and fish.

Whether those foods will be touched in some way by technology remains a high-stakes question. As for GM foods, the American public is somewhat skeptical: in a recent survey, about one-third of Americans report that they are actively avoiding GMOs or seek out non-GMO labels when shopping and purchasing foods. These consumers fear unsafe food and don't want biotechnologists to tamper with nature. This disconnect—between those who consume food and those who produce it—is only set to intensify as major agricultural companies work to develop further high-tech farming solutions to meet the needs of the growing population.

"I don't think we have a choice going forward. The world isn't getting smaller. We have to come up with a means of using less."

In the future, it may be possible to feed the world. But what if the world doesn't want the food?

A Short History

Genetically modified food is not new. The first such plant (the Flavr Savr tomato) was approved for human consumption and brought to market in 1994, but people didn't like the taste. Today, nine genetically modified food crops are commercially available in the United States (corn, soybean, squash, papaya, alfalfa, sugar beets, canola, potato and apples). Most were modified to increase resistance to disease or pests, or tolerance to a specific herbicide. Such crops have in fact been found to increase yields, with a recent study showing grain yield was up to 24.5 percent higher in genetically engineered corn.

Despite some consumer skepticism, many farmers don't have a problem with GM crops, says Jennie Schmidt, a farmer and registered dietician in Maryland. She says with a laugh that her farm is a "grocery store farm - we grow the ingredients you buy in products at the grocery store." Schmidt's father-in-law, who started the farm, watched the adoption of hybrid corn improve seeds in the 1930s and 1940s.

"It wasn't a difficult leap to see how well these hybrid corn seeds have done over the decades," she says. "So when the GMOs came out, it was a quicker adoption curve, because as farmers they had already been exposed to the first generation and this was just the next step."

Schmidt, for one, is excited about the gene-editing tool CRISPR and other ways biotechnologists can create food like apples or potatoes with a particular enzyme turned off so they don't go brown during oxidation. Other foods in the pipeline include disease-resistant citrus, low-gluten wheat, fungus-resistant bananas, and anti-browning mushrooms.

"We need to not judge our agriculture by yield per acre but nutrition per acre."

"I don't think we have a choice going forward," says Schmidt. "The world isn't getting smaller. We have to come up with a means of using less."

A Different Way Forward?

But others remain convinced that there are better ways to feed the planet. Andrew Kimball, executive director of the Center for Food Safety, a non-profit that promotes organic and sustainable agriculture, says the public has been sold a lie with biotech. "GMO technology is not proven as a food producer," he says. "It's just not being done anywhere at a large scale. Ninety-nine percent of GMOs are corn and soy, and they allow chemical companies to sell more chemicals. But that doesn't increase food or decrease hunger." Instead, Kimball advocates for a pivot from commodity agriculture to farms with crop diversity and animals.

Kimball also suggests a way to use land more appropriately: stop growing so much biofuel. Right now, in the U.S., more than 55 percent of our crop farmland is in corn and soy. About 40 percent of that goes into cars through ethanol, 40 percent is fed to animals and a good bit of the rest goes into high-fructose corn syrup. That leaves only a small amount to feed people, says Kimball. "If you want to feed the world, not just the U.S., you want to make sure to use that land to feed people," he says. "We need to not judge our agriculture by yield per acre but nutrition per acre."

Robert Streiffer, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, agrees that GMOs haven't really helped alleviate hunger. Glyphosate resistance, one of the traits that is most commonly used in genetically engineered crops, doesn't improve yield or allow crops to be grown in areas where they weren't able to be grown before. "Insect resistance through the insertion of a Bt gene can improve yield, but is mostly used for cotton (which is not a food crop) and corn which goes to feed cattle, a very inefficient method of feeding the hungry, to say the least," he says. Important research is being done in crops such as cassava, which could help relieve global hunger. But in his opinion, these researchers lack the profit potential needed to motivate large private funding sources, so they require more public-sector funding.

"A substantial portion of public opposition is as much about the lack of any perceived benefits for the consumers as it is for outright fear of health or environmental dangers."

"Public opposition to biotech foods is certainly a factor, but I expect this will slowly decline as labels indicating the presence of GE (genetically engineered) ingredients become more common, and as we continue to amass reassuring data on the comparative environmental safety of GE crops," says Streiffer. "A substantial portion of public opposition is as much about the lack of any perceived benefits for the consumers as it is for outright fear of health or environmental dangers."

One sign that the public may be willing to embrace some non-natural foods is the recent interest in cultured meat, which is grown in a lab from animal cells but doesn't require raising or killing animals. A study published last year in PLOS One found that 65 percent of 673 surveyed U.S. individuals would probably or definitely try cultured meat, while only 8.5 percent said they definitely would not. In the future, lab-grown food may become another way to create more food with fewer resources.

Danielle Nierenberg, president of the Food Tank, a nonprofit organization focused on building a global community of safe and healthy food, points to an even more immediate problem: food waste. Globally, about a third of food is thrown out or goes bad before it has a chance to be eaten. She says simply fixing roads and infrastructure in developing countries would go a long way toward ensuring that food reaches the hungry. Focusing on helping small farmers (who grow 70 percent of food around the globe), especially female farmers, would go a long way, she says.

Innovation on the Farm

In addition to good roads, those farmers need fertilizer. Nitrogen-based fertilizers may get a boost in the future from technologies that release nutrients slowly over time, like slow-release medicines based on nanotechnology. In field trials on rice in Sri Lanka, one such nanotech fertilizer increased crop yields by 10 percent, even though it delivered only half the amount of urea compared with traditional fertilizer, according to a study last year.

"I'm not afraid of the food I grow. We live in the same environment, and I feel completely safe."

One startup, the San-Francisco-based Biome Makers, is profiling microbial DNA to give farmers an idea of what their soil needs to better support crops. Joyn Bio, another new startup based in Boston and West Sacramento, is looking to engineer microbes that could reduce farming's reliance on nitrogen fertilizer, which is expensive and harms the environment. (Full disclosure: Joyn Bio and this magazine are funded by the same company, Leaps by Bayer, though leapsmag is editorially independent. Also, Bayer recently acquired Monsanto, the leading producer of genetically engineered seeds and the herbicide Roundup.)

Terry Wanzek, the farmer in North Dakota, says he'd be willing to try any new technology as long as it helps his bottom line – and increases sustainability. "I'm not afraid of the food I grow," he says of his genetically modified produce. "We eat the same food, we live in the same environment, and I feel completely safe."

Only time will tell if people several decades from now feel the same way. But no matter how their food is produced, one thing is certain: those people will need to eat.

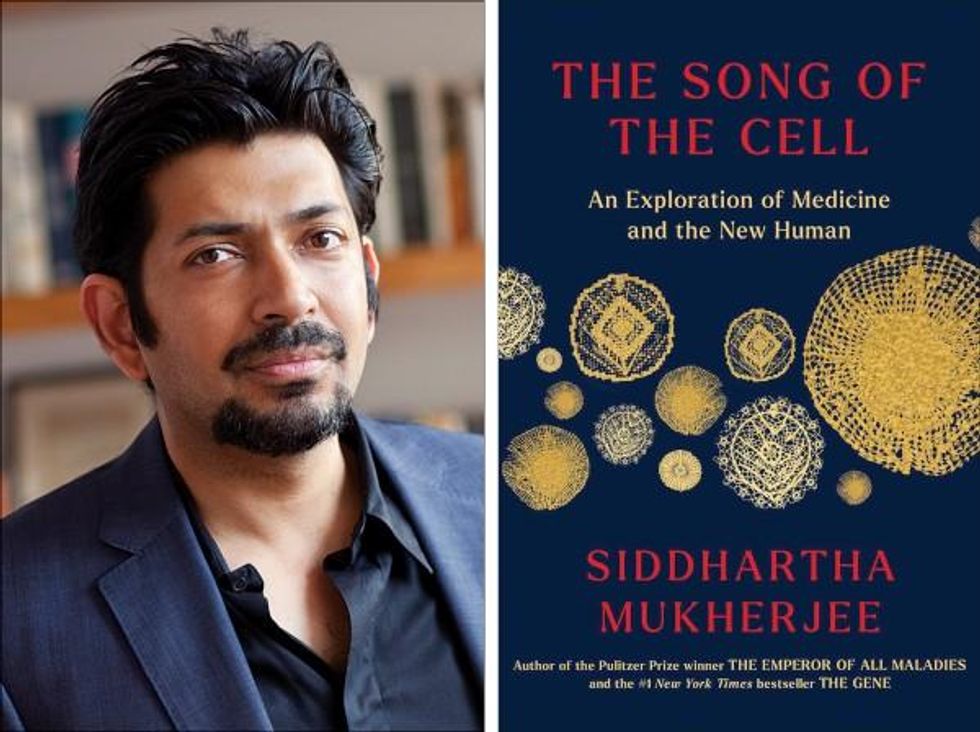

Life is Emerging: Review of Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Song of the Cell

A new book by Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee will be released from Simon & Schuster on October 25, 2022.

The DNA double helix is often the image spiraling at the center of 21st century advances in biomedicine and the growing bioeconomy. And yet, DNA is molecularly inert. DNA, the code for genes, is not alive and is not strictly necessary for life. Ought life be at the center of our communication of living systems? Is not the Cell a superior symbol of life and our manipulation of living systems?

A code for life isn’t a code without the life that instantiates it. A code for life must be translated. The cell is the basic unit of that translation. The cell is the minimal viable package of life as we know it. Therefore, cell biology is at the center of biomedicine’s greatest transformations, suggests Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee in his latest book, The Song of the Cell: The Exploration of Medicine and the New Human.

The Song of the Cell begins with the discovery of cells and of germ theory, featuring characters such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, who brought the cell “into intimate contact with pathology and medicine.” This intercourse would transform biomedicine, leading to the insight that we can treat disease by thinking at the cellular level. The slightest rearrangement of sick cells might be the path toward alleviating suffering for the organism: eroding the cell walls of a bacterium while sparing our human cells; inventing a medium that coaxes sperm and egg to dance into cellular union for in vitro fertilization (IVF); designing molecular missiles that home to the receptors decorating the exterior of cancer cells; teaching adult skin cells to remember their embryonic state for regenerative medicines.

Mukherjee uses the bulk of the book to elucidate key cell types in the human body, along with their “connective relationships” that enable key organs and organ systems to function. This includes the immune system, the heart, the brain, and so on. Mukherjee’s distinctive style features compelling anecdotes and human stories that animate the scientific (and unscientific) processes that have led to our current state of understanding. In his chapter on neurons and the brain, for example, he integrates Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s meticulous black ink sketches of neurons into Mukherjee’s own personal encounter with clinical depression. In one lucid section, he interviews Dr. Helen Mayberg, a pioneering neurologist who takes seriously the descriptive power of her patients’ metaphors, as they suffer from “caves,” “holes,” “voids,” and “force fields” that render their lives gray. Dr. Mayberg aims to stimulate patients’ neuronal cells in a manner that brings back the color.

Beyond exposing the insight and inventiveness that has arisen out of cell-based thinking, it seems that Mukherjee’s bigger project is an epistemological one. The early chapters of The Song of the Cell continually hint at the potential for redefining the basic unit of biology as the cell rather than the gene. The choice to center biomedicine around cells is, above all, a conspicuous choice not to center it around genes (the subject of Mukherjee’s previous book, The Gene), because genes dominate popular science communication.

This choice of cells over genes is most welcome. Cells are alive. Genes are not. Letters—such as the As, Cs, Gs, and Ts that represent the nucleotides of DNA, which make up our genes—must be synthesized into a word or poem or song that offers a glimpse into deeper truths. A key idea embedded in this thinking is that of emergence. Whether in ancient myth or modern art, creation tends to be an emergent process, not a linearly coded script. The cell is our current best guess for the basic unit of life’s emergence, turning a finite set of chemical building blocks—nucleic acids, proteins, sugars, fats—into a replicative, evolving system for fighting stasis and entropy. The cell’s song is one for our times, for it is the song of biology’s emergence out of chemistry and physics, into the “frenetically active process” of homeostasis.

Re-centering our view of biology has practical consequences, too, for how we think about diagnosing and treating disease, and for inventing new medicines. Centering cells presents a challenge: which type of cell to place at the center? Rather than default to the apparent simplicity of DNA as a symbol because it represents the one master code for life, the tension in defining the diversity of cells—a mapping process still far from complete in cutting-edge biology laboratories—can help to create a more thoughtful library of cellular metaphors to shape both the practice and communication of biology.

Further, effective problem solving is often about operating at the right level, or the right scale. The cell feels like appropriate level at which to interrogate many of the diseases that ail us, because the senses that guide our own perceptions of sickness and health—the smoldering pain of inflammation, the tunnel vision of a migraine, the dizziness of a fluttering heart—are emergent.

This, unfortunately, is sort of where Mukherjee leaves the reader, under-exploring the consequences of a biology of emergence. Many practical and profound questions have to do with the ways that each scale of life feeds back on the others. In a tome on Cells and “the future human” I wished that Mukherjee had created more space for seeking the ways that cells will shape and be shaped by the future, of humanity and otherwise.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts.

For example, when discussing the regenerative power of pluripotent stem cells, Mukherjee raises the philosophical thought experiment of the Delphic boat, also known as the Ship of Theseus. The boat is made of many pieces of wood, each of which is replaced for repairs over the years, with the boat’s structure unchanged. Eventually none of the boat’s original wood remains: Is it the same boat?

Mukherjee raises the Delphic boat in one paragraph at the end of the chapter on stem cells, as a metaphor related to the possibility of stem cell-enabled regeneration in perpetuity. He does not follow any of the threads of potential answers. Given the current state of cellular engineering, about which Mukherjee is a world expert from his work as a physician-scientist, this book could have used an entire section dedicated to probing this question and, importantly, the ways this thought experiment falls apart.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts. Wholeness at any one of these scales of life—organelle, cell, organ, body, ecosystem—is what is at stake if we allow biological reductionism to assume away the relation between those scales.

In other words, Mukherjee succeeds in providing a masterful and compelling narrative of the lives of many of the cells that emerge to enliven us. Like his previous books, it is a worthwhile read for anyone curious about the role of cells in disease and in health. And yet, he fails to offer the broader context of The Song of the Cell.

As leading agronomist and essayist Wes Jackson has written, “The sequence of amino acids that is at home in the human cell, when produced inside the bacterial cell, does not fold quite right. Something about the E. coli internal environment affects the tertiary structure of the protein and makes it inactive. The whole in this case, the E. coli cell, affects the part—the newly made protein. Where is the priority of part now?” [1]

Beyond the ways that different kingdoms of life translate the same genetic code, the practical situation for humanity today relates to the ways that the different disciplines of modern life use values and culture to influence our genes, cells, bodies, and environment. It may be that humans will soon become a bit like the Delphic boat, infused with the buzz of fresh cells to repopulate different niches within our bodies, for healthier, longer lives. But in biology, as in writing, a mixed metaphor can cause something of a cacophony. For we are not boats with parts to be replaced piecemeal. And nor are whales, nor alpine forests, nor topsoil. Life isn’t a sum of parts, and neither is a song that rings true.

[1] Wes Jackson, "Visions and Assumptions," in Nature as Measure (p. 52-53).

You won't score many glamor points for using a neti pot, but it could be a worthwhile asset in fighting Covid-19, according to the author's experience and recent research.

Twice a day, morning and night, I use a neti pot to send a warm saltwater solution coursing through one nostril and out the other to flush out debris and pathogens. I started many years ago because of sinus congestion and infections and it has greatly reduced those problems. Along with vaccination when it became available, it seems to have helped with protecting me from developing Covid-19 symptoms despite being of an age and weight that puts me squarely at risk.

Now that supposition of protection has been backed up with evidence from a solidly designed randomized clinical trial. It found that irrigating your sinuses twice a day with a simple saltwater solution can lead to an 8.5-fold reduction in hospitalization from Covid-19. The study is another example of recent research that points to easy and inexpensive ways to help protect yourself and help control the epidemic.

Amy Baxter, the physician researcher behind the study at Augusta University, Medical College of Georgia, began the study in 2020, before a vaccine or monoclonal antibodies became available to counter the virus. She wanted to be able to offer another line of defense for people with limited access to healthcare.

The nasal cavity is the front door that the SARS-CoV-2 virus typically uses to enter the body, latching on to the ACE2 receptors on cells lining those tissue compartments to establish infection. Once the virus replicates here, infection spreads into the lungs and often other parts of the body, including the brain and gut. Some studies have shown that a mouthwash could reduce the viral load, but any effect on disease progression was less clear. Baxter reasoned that reducing the amount of virus in the nose might give the immune system a better chance to react and control that growth before it got out of hand.

She decided to test this approach in patients who had just tested positive for Covid-19, were over 55 years of age, and often had other risk factors for developing serious symptoms. It was the quickest and easiest way to get results. A traditional prevention study would have required many more volunteers, taken a longer period of follow up, and cost money she did not have.

The trial enrolled 79 participants within 24 hours of testing positive for Covid-19, and they agreed to follow the regimen of twice daily nasal irrigation. They were followed for 28 days. One patient was hospitalized; a 1.27% rate compared with 11% in a national sample control group of similar age people who tested positive for Covid-19. Patients who strictly adhered to nasal irrigation had fewer, shorter and less severe symptoms than people in the study who missed some of their saline rinses.

Baxter initially made the results of her clinical trial available as a preprint in the summer of 2021 and was dismayed when many of the comments were from anti-vaxxers who argued this was a reason why you did not need to get vaccinated. That was not her intent.

There are several mechanisms that explain why warm saltwater is so effective. First and most obvious is the physical force of the water that sweeps away debris just as a rainstorm sends trash into a street gutter and down a storm drain. It also lubricates the cilia, small hair-like structures whose job it is to move detritus away from cells for expulsion. Cilia are rich in ACE2 receptors and keeping them moving makes it harder for the virus to latch on to the receptors.

It turns out the saline has a direct effect on the virus itself. SARS-CoV-2 becomes activated when an enzyme called furin snips off part of its molecular structure, which allows the virus to grab on to the ACE2 receptor, but saline inhibits this process. Once inside a cell the virus replicates best in a low salt environment, but nasal cells absorb salt from the irrigation, which further slows viral replication, says Baxter.

Finally, “salt improves the jellification of liquid, it makes better and stickier mucus so that you can get those virus out,” she explains, lamenting, “Nobody cares about snot. I do now.”

She initially made the results of her clinical trial available as a preprint in the summer of 2021 and was dismayed when many of the comments were from anti-vaxxers who argued this was a reason why you did not need to get vaccinated. That was not her intent. Two journals rejected the paper, and Baxter believes getting caught up in the polarizing politics of Covid-19 was an important part of the reason why. She says that editors “didn't want to be associated with something that was being used by anti-vaxxers.” She strongly supports vaccination but realizes that additional and alternative approaches also are needed.

Premeasured packets of saline are inexpensive and can be purchased at any drug store. They are safe to use several times a day. Say you’re vaccinated but were in a situation where you fear you might have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2; an extra irrigation will clear out your sinuses and may reduce the risk of that possible exposure.

Baxter plans no further study in this area. She is returning to her primary research focus, which is pain control and reducing opioid use, but she hopes that others will expand on what she had done.