The Algorithm Will See You Now

Artificial intelligence in medicine, still in an early phase, stands to transform how doctors and nurses spend their time.

There's a quiet revolution going on in medicine. It's driven by artificial intelligence, but paradoxically, new technology may put a more human face on healthcare.

AI's usefulness in healthcare ranges far and wide.

Artificial intelligence is software that can process massive amounts of information and learn over time, arriving at decisions with striking accuracy and efficiency. It offers greater accuracy in diagnosis, exponentially faster genome sequencing, the mining of medical literature and patient records at breathtaking speed, a dramatic reduction in administrative bureaucracy, personalized medicine, and even the democratization of healthcare.

The algorithms that bring these advantages won't replace doctors; rather, by offloading some of the most time-consuming tasks in healthcare, providers will be able to focus on personal interactions with patients—listening, empathizing, educating and generally putting the care back in healthcare. The relationship can focus on the alleviation of suffering, both the physical and emotional kind.

Challenges of Getting AI Up and Running

The AI revolution, still in its early phase in medicine, is already spurring some amazing advances, despite the fact that some experts say it has been overhyped. IBM's Watson Health program is a case in point. IBM capitalized on Watson's ability to process natural language by designing algorithms that devour data like medical articles and analyze images like MRIs and medical slides. The algorithms help diagnose diseases and recommend treatment strategies.

But Technology Review reported that a heavily hyped partnership with the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston fell apart in 2017 because of a lack of data in the proper format. The data existed, just not in a way that the voraciously data-hungry AI could use to train itself.

The hiccup certainly hasn't dampened the enthusiasm for medical AI among other tech giants, including Google and Apple, both of which have invested billions in their own healthcare projects. At this point, the main challenge is the need for algorithms to interpret a huge diversity of data mined from medical records. This can include everything from CT scans, MRIs, electrocardiograms, x-rays, and medical slides, to millions of pages of medical literature, physician's notes, and patient histories. It can even include data from implantables and wearables such as the Apple Watch and blood sugar monitors.

None of this information is in anything resembling a standard format across and even within hospitals, clinics, and diagnostic centers. Once the algorithms are trained, however, they can crunch massive amounts of data at blinding speed, with an accuracy that matches and sometimes even exceeds that of highly experienced doctors.

Genome sequencing, for example, took years to accomplish as recently as the early 2000s. The Human Genome Project, the first sequencing of the human genome, was an international effort that took 13 years to complete. In April of this year, Rady Children's Institute for Genomic Medicine in San Diego used an AI-powered genome sequencing algorithm to diagnose rare genetic diseases in infants in about 20 hours, according to ScienceDaily.

"Patient care will always begin and end with the doctor."

Dr. Stephen Kingsmore, the lead author of an article published in Science Translational Medicine, emphasized that even though the algorithm helped guide the treatment strategies of neonatal intensive care physicians, the doctor was still an indispensable link in the chain. "Some people call this artificial intelligence, we call it augmented intelligence," he says. "Patient care will always begin and end with the doctor."

One existing trend is helping to supply a great amount of valuable data to algorithms—the electronic health record. Initially blamed for exacerbating the already crushing workload of many physicians, the EHR is emerging as a boon for algorithms because it consolidates all of a patient's data in one record.

Examples of AI in Action Around the Globe

If you're a parent who has ever taken a child to the doctor with flulike symptoms, you know the anxiety of wondering if the symptoms signal something serious. Kang Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., the founding director of the Institute for Genomic Medicine at the University of California at San Diego, and colleagues developed an AI natural language processing model that used deep learning to analyze the EHRs of 1.3 million pediatric visits to a clinic in Guanzhou, China.

The AI identified common childhood diseases with about the same accuracy as human doctors, and it was even able to split the diagnoses into two categories—common conditions such as flu, and serious, life-threatening conditions like meningitis. Zhang has emphasized that the algorithm didn't replace the human doctor, but it did streamline the diagnostic process and could be used in a triage capacity when emergency room personnel need to prioritize the seriously ill over those suffering from common, less dangerous ailments.

AI's usefulness in healthcare ranges far and wide. In Uganda and several other African nations, AI is bringing modern diagnostics to remote villages that have no access to traditional technologies such as x-rays. The New York Times recently reported that there, doctors are using a pocket-sized, hand-held ultrasound machine that works in concert with a cell phone to image and diagnose everything from pneumonia (a common killer of children) to cancerous tumors.

The beauty of the highly portable, battery-powered device is that ultrasound images can be uploaded on computers so that physicians anywhere in the world can review them and weigh in with their advice. And the images are instantly incorporated into the patient's EHR.

Jonathan Rothberg, the founder of Butterfly Network, the Connecticut company that makes the device, told The New York Times that "Two thirds of the world's population gets no imaging at all. When you put something on a chip, the price goes down and you democratize it." The Butterfly ultrasound machine, which sells for $2,000, promises to be a game-changer in remote areas of Africa, South America, and Asia, as well as at the bedsides of patients in developed countries.

AI algorithms are rapidly emerging in healthcare across the U.S. and the world. China has become a major international player, set to surpass the U.S. this year in AI capital investment, the translation of AI research into marketable products, and even the number of often-cited research papers on AI. So far the U.S. is still the leader, but some experts describe the relationship between the U.S. and China as an AI cold war.

"The future of machine learning isn't sentient killer robots. It's longer human lives."

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration expanded its approval of medical algorithms from two in all of 2017 to about two per month throughout 2018. One of the first fields to be impacted is ophthalmology.

One algorithm, developed by the British AI company DeepMind (owned by Alphabet, the parent company of Google), instantly scans patients' retinas and is able to diagnose diabetic retinopathy without needing an ophthalmologist to interpret the scans. This means diabetics can get the test every year from their family physician without having to see a specialist. The Financial Times reported in March that the technology is now being used in clinics throughout Europe.

In Copenhagen, emergency service dispatchers are using a new voice-processing AI called Corti to analyze the conversations in emergency phone calls. The algorithm analyzes the verbal cues of callers, searches its huge database of medical information, and provides dispatchers with onscreen diagnostic information. Freddy Lippert, the CEO of EMS Copenhagen, notes that the algorithm has already saved lives by expediting accurate diagnoses in high-pressure situations where time is of the essence.

Researchers at the University of Nottingham in the UK have even developed a deep learning algorithm that predicts death more accurately than human clinicians. The algorithm incorporates data from a huge range of factors in a chronically ill population, including how many fruits and vegetables a patient eats on a daily basis. Dr. Stephen Weng, lead author of the study, published in PLOS ONE, said in a press release, "We found machine learning algorithms were significantly more accurate in predicting death than the standard prediction models developed by a human expert."

New digital technologies are allowing patients to participate in their healthcare as never before. A feature of the new Apple Watch is an app that detects cardiac arrhythmias and even produces an electrocardiogram if an abnormality is detected. The technology, approved by the FDA, is helping cardiologists monitor heart patients and design interventions for those who may be at higher risk of a cardiac event like a stroke.

If having an algorithm predict your death sends a shiver down your spine, consider that algorithms may keep you alive longer. In 2018, technology reporter Tristan Greene wrote for Medium that "…despite the unending deluge of panic-ridden articles declaring AI the path to apocalypse, we're now living in a world where algorithms save lives every day. The future of machine learning isn't sentient killer robots. It's longer human lives."

The Risks of AI Compiling Your Data

To be sure, the advent of AI-infused medical technology is not without its risks. One risk is that the use of AI wearables constantly monitoring our vital signs could turn us into a nation of hypochondriacs, racing to our doctors every time there's a blip in some vital sign. Such a development could stress an already overburdened system that suffers from, among other things, a shortage of doctors and nurses. Another risk has to do with the privacy protections on the massive repository of intimately personal information that AI will have on us.

In an article recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Australian researcher Kit Huckvale and colleagues examined the handling of data by 36 smartphone apps that assisted people with either depression or smoking cessation, two areas that could lend themselves to stigmatization if they fell into the wrong hands.

Out of the 36 apps, 33 shared their data with third parties, despite the fact that just 25 of those apps had a privacy policy at all and out of those, only 23 stated that data would be shared with third parties. The recipients of all that data? It went almost exclusively to Facebook and Google, to be used for advertising and marketing purposes. But there's nothing to stop it from ending up in the hands of insurers, background databases, or any other entity.

Even when data isn't voluntarily shared, any digital information can be hacked. EHRs and even wearable devices share the same vulnerability as any other digital record or device. Still, the promise of AI to radically improve efficiency and accuracy in healthcare is hard to ignore.

AI Can Help Restore Humanity to Medicine

Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute and author of the new book Deep Medicine, says that AI gives doctors and nurses the most precious gift of all: time.

Topol welcomes his patients' use of the Apple Watch cardiac feature and is optimistic about the ways that AI is revolutionizing medicine. He says that the watch helps doctors monitor how well medications are working and has already helped to prevent strokes. But in addition to that, AI will help bring the humanity back to a profession that has become as cold and hard as a stainless steel dissection table.

"When I graduated from medical school in the 1970s," he says, "you had a really intimate relationship with your doctor." Over the decades, he has seen that relationship steadily erode as medical organizations demanded that doctors see more and more patients within ever-shrinking time windows.

"Doctors have no time to think, to communicate. We need to restore the mission in medicine."

In addition to that, EHRs have meant that doctors and nurses are getting buried in paperwork and administrative tasks. This is no doubt one reason why a recent study by the World Health Organization showed that worldwide, about 50 percent of doctors suffer from burnout. People who are utterly exhausted make more mistakes, and medical clinicians are no different from the rest of us. Only medical mistakes have unacceptably high stakes. According to its website, Johns Hopkins University recently announced that in the U.S. alone, 250,000 people die from medical mistakes each year.

"Doctors have no time to think, to communicate," says Topol. "We need to restore the mission in medicine." AI is giving doctors more time to devote to the thing that attracted them to medicine in the first place—connecting deeply with patients.

There is a real danger at this juncture, though, that administrators aware of the time-saving aspects of AI will simply push doctors to see more patients, read more tests, and embrace an even more crushing workload.

"We can't leave it to the administrators to just make things worse," says Topol. "Now is the time for doctors to advocate for a restoration of the human touch. We need to stand up for patients and for the patient-doctor relationship."

AI could indeed be a game changer, he says, but rather than squander the huge benefits of more time, "We need a new equation going forward."

Scientists Are Working to Decipher the Puzzle of ‘Broken Heart Syndrome’

Elaine Kamil had just returned home after a few days of business meetings in 2013 when she started having chest pains. At first Kamil, then 66, wasn't worried—she had had some chest pain before and recently went to a cardiologist to do a stress test, which was normal.

"I can't be having a heart attack because I just got checked," she thought, attributing the discomfort to stress and high demands of her job. A pediatric nephrologist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, she takes care of critically ill children who are on dialysis or are kidney transplant patients. Supporting families through difficult times and answering calls at odd hours is part of her daily routine, and often leaves her exhausted.

She figured the pain would go away. But instead, it intensified that night. Kamil's husband drove her to the Cedars-Sinai hospital, where she was admitted to the coronary care unit. It turned out she wasn't having a heart attack after all. Instead, she was diagnosed with a much less common but nonetheless dangerous heart condition called takotsubo syndrome, or broken heart syndrome.

A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart is obstructed—such as when an artery is blocked—causing heart muscle tissue to die. In takotsubo syndrome, the blood flow isn't blocked, but the heart doesn't pump it properly. The heart changes its shape and starts to resemble a Japanese fishing device called tako-tsubo, a clay pot with a wider body and narrower mouth, used to catch octopus.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks," explains Noel Bairey Merz, the cardiologist at Cedar Sinai who Kamil went to see after she was discharged.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks."

But even though the heart isn't permanently damaged, mortality rates due to takotsubo syndrome are comparable to those of a heart attack, Merz notes—about 4-5 percent of patients die from the attack, and 20 percent within the next five years. "It's as bad as a heart attack," Merz says—only it's much less known, even to doctors. The condition affects only about 1 percent of people, and there are around 15,000 new cases annually. It's diagnosed using a cardiac ventriculogram, an imaging test that allows doctors to see how the heart pumps blood.

Scientists don't fully understand what causes Takotsubo syndrome, but it usually occurs after extreme emotional or physical stress. Doctors think it's triggered by a so-called catecholamine storm, a phenomenon in which the body releases too much catecholamines—hormones involved in the fight-or-flight response. Evolutionarily, when early humans lived in savannas or forests and had to either fight off predators or flee from them, these hormones gave our ancestors the needed strength and stamina to take either action. Released by nerve endings and by the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys, these hormones still flood our bodies in moments of stress, but an overabundance of them could sometimes be damaging.

Elaine Kamil

A study by scientists at Harvard Medical School linked increased risk of takotsubo to higher activity in the amygdala, a brain region responsible for emotions that's involved in responses to stress. The scientists believe that chronic stress makes people more susceptible to the syndrome. Notably, one small study suggested that the number of Takotsubo cases increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are no specific drugs to treat takotsubo, so doctors rely on supportive therapies, which include medications typically used for high blood pressure and heart failure. In most cases, the heart returns to its normal shape within a few weeks. "It's a spontaneous recovery—the catecholamine storm is resolved, the injury trigger is removed and the heart heals itself because our bodies have an amazing healing capacity," Merz says. It also helps that tissues remain intact. 'The heart cells don't die, they just aren't functioning properly for some time."

That's the good news. The bad news is that takotsubo is likely to strike again—in 5-20 percent of patients the condition comes back, sometimes more severe than before.

That's exactly what happened to Kamil. After getting her diagnosis in 2013, she realized that she actually had a previous takotsubo episode. In 2010, she experienced similar symptoms after her son died. "The night after he died, I was having severe chest pain at night, but I was too overwhelmed with grief to do anything about it," she recalls. After a while, the pain subsided and didn't return until three years later.

For weeks after her second attack, she felt exhausted, listless and anxious. "You lose confidence in your body," she says. "You have these little twinges on your chest, or if you start having arrhythmia, and you wonder if this is another episode coming up. It's really unnerving because you don't know how to read these cues." And that's very typical, Merz says. Even when the heart muscle appears to recover, patients don't return to normal right away. They have shortens of breath, they can't exercise, and they stay anxious and worried for a while.

Women over the age of 50 are diagnosed with takotsubo more often than other demographics. However, it happens in men too, although it typically strikes after physical stress, such as a triathlon or an exhausting day of cycling. Young people can also get takotsubo. Older patients are hospitalized more often, but younger people tend to have more severe complications. It could be because an older person may go for a jog while younger one may run a marathon, which would take a stronger toll on the body of a person who's predisposed to the condition.

Notably, the emotional stressors don't always have to be negative—the heart muscle can get out of shape from good emotions, too. "There have been case reports of takotsubo at weddings," Merz says. Moreover, one out of three or four takotsubo patients experience no apparent stress, she adds. "So it could be that it's not so much the catecholamine storm itself, but the body's reaction to it—the physiological reaction deeply embedded into out physiology," she explains.

Merz and her team are working to understand what makes people predisposed to takotsubo. They think a person's genetics play a role, but they haven't yet pinpointed genes that seem to be responsible. Genes code for proteins, which affect how the body metabolizes various compounds, which, in turn, affect the body's response to stress. Pinning down the protein involved in takotsubo susceptibility would allow doctors to develop screening tests and identify those prone to severe repeating attacks. It will also help develop medications that can either prevent it or treat it better than just waiting for the body to heal itself.

Researchers at the Imperial College London found that elevated levels of certain types of microRNAs—molecules involved in protein production—increase the chances of developing takotsubo.

In one study, researchers tried treating takotsubo in mice with a drug called suberanilohydroxamic acid, or SAHA, typically used for cancer treatment. The drug improved cardiac health and reversed the broken heart in rodents. It remains to be seen if the drug would have a similar effect on humans. But identifying a drug that shows promise is progress, Merz says. "I'm glad that there's research in this area."

This article was originally published by Leaps.org on July 28, 2021.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Did Anton the AI find a new treatment for a deadly cancer?

Researchers used a supercomputer to learn about the subtle movement of a cancer-causing molecule, and then they found the precise drug that can recognize that motion.

Bile duct cancer is a rare and aggressive form of cancer that is often difficult to diagnose. Patients with advanced forms of the disease have an average life expectancy of less than two years.

Many patients who get cancer in their bile ducts – the tubes that carry digestive fluid from the liver to the small intestine – have mutations in the protein FGFR2, which leads cells to grow uncontrollably. One treatment option is chemotherapy, but it’s toxic to both cancer cells and healthy cells, failing to distinguish between the two. Increasingly, cancer researchers are focusing on biomarker directed therapy, or making drugs that target a particular molecule that causes the disease – FGFR2, in the case of bile duct cancer.

A problem is that in targeting FGFR2, these drugs inadvertently inhibit the FGFR1 protein, which looks almost identical. This causes elevated phosphate levels, which is a sign of kidney damage, so doses are often limited to prevent complications.

In recent years, though, a company called Relay has taken a unique approach to picking out FGFR2, using a powerful supercomputer to simulate how proteins move and change shape. The team, leveraging this AI capability, discovered that FGFR2 and FGFR1 move differently, which enabled them to create a more precise drug.

Preliminary studies have shown robust activity of this drug, called RLY-4008, in FGFR2 altered tumors, especially in bile duct cancer. The drug did not inhibit FGFR1 or cause significant side effects. “RLY-4008 is a prime example of a precision oncology therapeutic with its highly selective and potent targeting of FGFR2 genetic alterations and resistance mutations,” says Lipika Goyal, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is a principal investigator of Relay’s phase 1-2 clinical trial.

Boosts from AI and a billionaire

Traditional drug design has been very much a case of trial and error, as scientists investigate many molecules to see which ones bind to the intended target and bind less to other targets.

“It’s being done almost blindly, without really being guided by structure, so it fails very often,” says Olivier Elemento, associate director of the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Cornell. “The issue is that they are not sampling enough molecules to cover some of the chemical space that would be specific to the target of interest and not specific to others.”

Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

Some scientists have tried to use X-rays of crystallized proteins to look at the structure of proteins and design better drugs. But they have failed to account for an important factor: proteins are moving and constantly folding into different shapes.

David Shaw, a hedge fund billionaire, wanted to help improve drug discovery and understood that a key obstacle was that computer models of molecular dynamics were limited; they simulated motion for less than 10 millionths of a second.

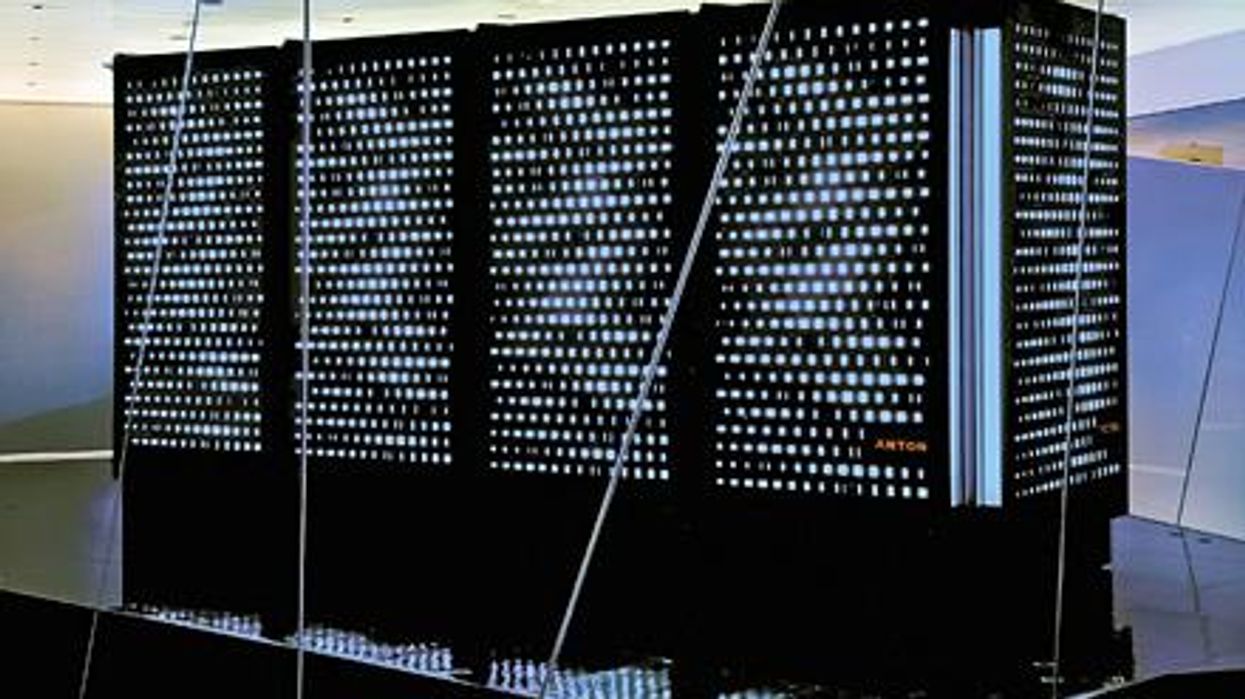

In 2001, Shaw set up his own research facility, D.E. Shaw Research, to create a supercomputer that would be specifically designed to simulate protein motion. Seven years later, he succeeded in firing up a supercomputer that can now conduct high speed simulations roughly 100 times faster than others. Called Anton, it has special computer chips to enable this speed, and its software is powered by AI to conduct many simulations.

After creating the supercomputer, Shaw teamed up with leading scientists who were interested in molecular motion, and they founded Relay Therapeutics.

Elemento believes that Relay’s approach is highly beneficial in designing a better drug for bile duct cancer. “Relay Therapeutics has a cutting-edge approach for molecular dynamics that I don’t believe any other companies have, at least not as advanced.” Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

How it works

Relay used both experimental and computational approaches to design RLY-4008. The team started out by taking X-rays of crystallized versions of both their intended target, FGFR2, and the almost identical FGFR1. This enabled them to get a 3D snapshot of each of their structures. They then fed the X-rays into the Anton supercomputer to simulate how the proteins were likely to move.

Anton’s simulations showed that the FGFR1 protein had a flap that moved more frequently than FGFR2. Based on this distinct motion, the team tried to design a compound that would recognize this flap shifting around and bind to FGFR2 while steering away from its more active lookalike.

For that, they went back Anton, using the supercomputer to simulate the behavior of thousands of potential molecules for over a year, looking at what made a particular molecule selective to the target versus another molecule that wasn’t. These insights led them to determine the best compounds to make and test in the lab and, ultimately, they found that RLY-4008 was the most effective.

Promising results so far

Relay began phase 1-2 trials in 2020 and will continue until 2024. Preliminary results showed that, in the 17 patients taking a 70 mg dose of RLY-4008, the drug worked to shrink tumors in 88 percent of patients. This was a significant increase compared to other FGFR inhibitors. For instance, Futibatinib, which recently got FDA approval, had a response rate of only 42 percent.

Across all dose levels, RLY-4008 shrank tumors by 63 percent in 38 patients. In more good news, the drug didn’t elevate their phosphate levels, which suggests that it could be taken without increasing patients’ risk for kidney disease.

“Objectively, this is pretty remarkable,” says Elemento. “In a small patient study, you have a molecule that is able to shrink tumors in such a high fraction of patients. It is unusual to see such good results in a phase 1-2 trial.”

A simulated future

The research team is continuing to use molecular dynamic simulations to develop other new drug, such as one that is being studied in patients with solid tumors and breast cancer.

As for their bile duct cancer drug, RLY-4008, Relay plans by 2024 to have tested it in around 440 patients. “The mature results of the phase 1-2 trial are highly anticipated,” says Goyal, the principal investigator of the trial.

Sameek Roychowdhury, an oncologist and associate professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University, highlights the need for caution. “This has early signs of benefit, but we will look forward to seeing longer term results for benefit and side effect profiles. We need to think a few more steps ahead - these treatments are like the ’Whack-a-Mole game’ where cancer finds a way to become resistant to each subsequent drug.”

“I think the issue is going to be how durable are the responses to the drug and what are the mechanisms of resistance,” says Raymond Wadlow, an oncologist at the Inova Medical Group who specializes in gastrointestinal and haematological cancer. “But the results look promising. It is a much more selective inhibitor of the FGFR protein and less toxic. It’s been an exciting development.”