The Case for an Outright Ban on Facial Recognition Technology

Some experts worry that facial recognition technology is a dangerous enough threat to our basic rights that it should be entirely banned from police and government use.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question, which we posed to experts with different perspectives: "Do you think the use of facial recognition technology by the police or government should be banned? If so, why? If not, what limits, if any, should be placed on its use?"]

In a surprise appearance at the tail end of Amazon's much-hyped annual product event last month, CEO Jeff Bezos casually told reporters that his company is writing its own facial recognition legislation.

The use of computer algorithms to analyze massive databases of footage and photographs could render human privacy extinct.

It seems that when you're the wealthiest human alive, there's nothing strange about your company––the largest in the world profiting from the spread of face surveillance technology––writing the rules that govern it.

But if lawmakers and advocates fall into Silicon Valley's trap of "regulating" facial recognition and other forms of invasive biometric surveillance, that's exactly what will happen.

Industry-friendly regulations won't fix the dangers inherent in widespread use of face scanning software, whether it's deployed by governments or for commercial purposes. The use of this technology in public places and for surveillance purposes should be banned outright, and its use by private companies and individuals should be severely restricted. As artificial intelligence expert Luke Stark wrote, it's dangerous enough that it should be outlawed for "almost all practical purposes."

Like biological or nuclear weapons, facial recognition poses such a profound threat to the future of humanity and our basic rights that any potential benefits are far outweighed by the inevitable harms.

We live in cities and towns with an exponentially growing number of always-on cameras, installed in everything from cars to children's toys to Amazon's police-friendly doorbells. The use of computer algorithms to analyze massive databases of footage and photographs could render human privacy extinct. It's a world where nearly everything we do, everywhere we go, everyone we associate with, and everything we buy — or look at and even think of buying — is recorded and can be tracked and analyzed at a mass scale for unimaginably awful purposes.

Biometric tracking enables the automated and pervasive monitoring of an entire population. There's ample evidence that this type of dragnet mass data collection and analysis is not useful for public safety, but it's perfect for oppression and social control.

Law enforcement defenders of facial recognition often state that the technology simply lets them do what they would be doing anyway: compare footage or photos against mug shots, drivers licenses, or other databases, but faster. And they're not wrong. But the speed and automation enabled by artificial intelligence-powered surveillance fundamentally changes the impact of that surveillance on our society. Being able to do something exponentially faster, and using significantly less human and financial resources, alters the nature of that thing. The Fourth Amendment becomes meaningless in a world where private companies record everything we do and provide governments with easy tools to request and analyze footage from a growing, privately owned, panopticon.

Tech giants like Microsoft and Amazon insist that facial recognition will be a lucrative boon for humanity, as long as there are proper safeguards in place. This disingenuous call for regulation is straight out of the same lobbying playbook that telecom companies have used to attack net neutrality and Silicon Valley has used to scuttle meaningful data privacy legislation. Companies are calling for regulation because they want their corporate lawyers and lobbyists to help write the rules of the road, to ensure those rules are friendly to their business models. They're trying to skip the debate about what role, if any, technology this uniquely dangerous should play in a free and open society. They want to rush ahead to the discussion about how we roll it out.

We need spaces that are free from government and societal intrusion in order to advance as a civilization.

Facial recognition is spreading very quickly. But backlash is growing too. Several cities have already banned government entities, including police and schools, from using biometric surveillance. Others have local ordinances in the works, and there's state legislation brewing in Michigan, Massachusetts, Utah, and California. Meanwhile, there is growing bipartisan agreement in U.S. Congress to rein in government use of facial recognition. We've also seen significant backlash to facial recognition growing in the U.K., within the European Parliament, and in Sweden, which recently banned its use in schools following a fine under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

At least two frontrunners in the 2020 presidential campaign have backed a ban on law enforcement use of facial recognition. Many of the largest music festivals in the world responded to Fight for the Future's campaign and committed to not use facial recognition technology on music fans.

There has been widespread reporting on the fact that existing facial recognition algorithms exhibit systemic racial and gender bias, and are more likely to misidentify people with darker skin, or who are not perceived by a computer to be a white man. Critics are right to highlight this algorithmic bias. Facial recognition is being used by law enforcement in cities like Detroit right now, and the racial bias baked into that software is doing harm. It's exacerbating existing forms of racial profiling and discrimination in everything from public housing to the criminal justice system.

But the companies that make facial recognition assure us this bias is a bug, not a feature, and that they can fix it. And they might be right. Face scanning algorithms for many purposes will improve over time. But facial recognition becoming more accurate doesn't make it less of a threat to human rights. This technology is dangerous when it's broken, but at a mass scale, it's even more dangerous when it works. And it will still disproportionately harm our society's most vulnerable members.

Persistent monitoring and policing of our behavior breeds conformity, benefits tyrants, and enriches elites.

We need spaces that are free from government and societal intrusion in order to advance as a civilization. If technology makes it so that laws can be enforced 100 percent of the time, there is no room to test whether those laws are just. If the U.S. government had ubiquitous facial recognition surveillance 50 years ago when homosexuality was still criminalized, would the LGBTQ rights movement ever have formed? In a world where private spaces don't exist, would people have felt safe enough to leave the closet and gather, build community, and form a movement? Freedom from surveillance is necessary for deviation from social norms as well as to dissent from authority, without which societal progress halts.

Persistent monitoring and policing of our behavior breeds conformity, benefits tyrants, and enriches elites. Drawing a line in the sand around tech-enhanced surveillance is the fundamental fight of this generation. Lining up to get our faces scanned to participate in society doesn't just threaten our privacy, it threatens our humanity, and our ability to be ourselves.

[Editor's Note: Read the opposite perspective here.]

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

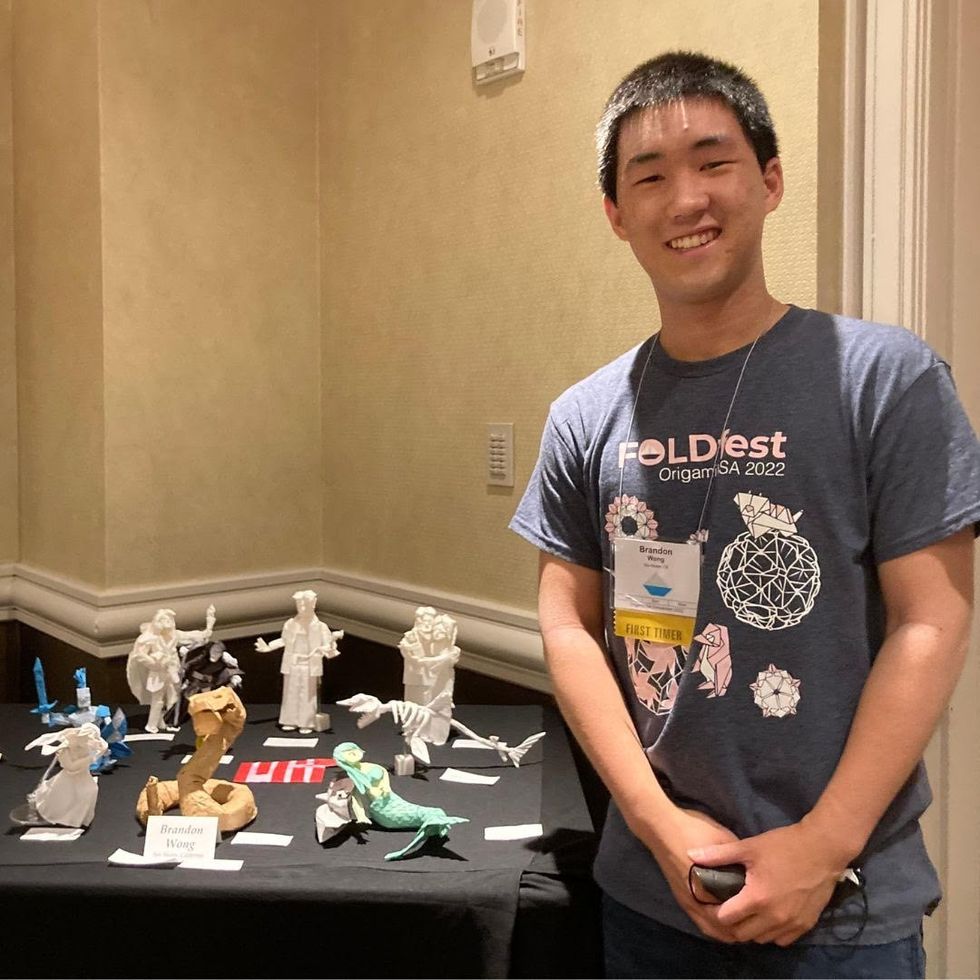

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”