The Dangers of Hype: How a Bold Claim and Sensational Media Unraveled a Company

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

This past March, headlines suddenly flooded the Internet about a startup company called Nectome. Founded by two graduates of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the new company was charging people $10,000 to join a waiting list to have their brains embalmed, down to the last neuron, using an award-winning chemical compound.

While the lay public presumably burnt their wills and grew ever more excited about the end of humanity's quest for immortality, neurologists let out a collective sigh.

Essentially, participants' brains would turn to a substance like glass and remain in a state of near-perfect preservation indefinitely. "If memories can truly be preserved by a sufficiently good brain banking technique," Nectome's website explains, "we believe that within the century it could become feasible to digitize your preserved brain and use that information to recreate your mind." But as with most Faustian bargains, Nectome's proposition came with a serious caveat -- death.

That's right, in order for Nectome's process to properly preserve your connectome, the comprehensive map of the brain's neural connections, you must be alive (and under anesthesia) while the fluid is injected. This way, the company postulates, when the science advances enough to read and extract your memories someday, your vitrified brain will still contain your perfectly preserved essence--which can then be digitally recreated as a computer simulation.

Almost immediately this story gained buzz with punchy headlines: "Startup wants to upload your brain to the cloud, but has to kill you to do it," "San Junipero is real: Nectome wants to upload your brain," and "New tech firm promises eternal life, but you have to die."

While the lay public presumably burnt their wills and grew ever more excited about the end of humanity's quest for immortality, neurologists let out a collective sigh -- hype had struck the scientific community once again.

The truth about Nectome is that its claims are highly speculative and no hard science exists to suggest that our connectome is the key to our 'being,' nor that it can ever be digitally revived. "We haven't come even close to understanding even the most basic types of functioning in the brain," says neuroscientist Alex Fox, who was educated at the University of Queensland in Australia. "Memory storage in the brain is only a theoretical concept [and] there are some seriously huge gaps in our knowledge base that stand in the way of testing [the connectome] theory."

After the Nectome story broke, Harvard computational neuroscientist Sam Gershman tweeted out:

"Didn't anyone tell them that we've known the C Elegans (a microscopic worm) connectome for over a decade but haven't figured out how to reconstruct all of their memories? And that's only 7000 synapses compared to the trillions of synapses in the human brain!"

Hype can come from researchers themselves, who are under an enormous amount of pressure to publish original work and maintain funding.

How media coverage of Nectome went from an initial fastidiously researched article in the MIT Technology Review by veteran science journalist Antonio Regalado to the click-bait frenzy it became is a prime example of the 'science hype' phenomenon. According to Adam Auch, who holds a doctorate in philosophy from Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, "Hype is a feature of all stages of the scientific dissemination process, from the initial circulation of preliminary findings within particular communities of scientists, to the process by which such findings come to be published in peer-reviewed journals, to the subsequent uptake these findings receive from the non-specialist press and the general public."

In the case of Nectome, hype was present from the word go. Riding the high of several major wins, including having raised over one million dollars in funding and partnering with well-known MIT neurologist Edward Boyden, Nectome founders Michael McCanna and Robert McIntyre launched their website on March 1, 2018. Just one month prior, they were able to purchase and preserve a newly deceased corpse in Portland, Oregon, showing that vitrifixation, their method of chemical preservation, could be used on a human specimen. It had previously won an award for preserving every synaptic structure on a rabbit brain.

The Nectome mission statement, found on its website, is laced with saccharine language that skirts the unproven nature of the procedure the company is peddling for big bucks: "Our mission is to preserve your brain well enough to keep all its memories intact: from that great chapter of your favorite book to the feeling of cold winter air, baking an apple pie, or having dinner with your friends and family."

This rhetoric is an example of hype that can come from researchers themselves, who are under an enormous amount of pressure to publish original work and maintain funding. As a result, there is a constant push to present science as "groundbreaking" when really, as is apparently the case with Nectome, it is only a small piece in a much larger effort.

Calling out the audacity of Nectome's posited future, neuroscientist Gershman commented to another publication, "The important question is whether the connectome is sufficient for memory: Can I reconstruct all memories knowing only the connections between neurons? The answer is almost certainly no, given our knowledge about how memories are stored (itself a controversial topic)."

The former home page of Nectome's website, which has now been replaced by a statement titled, "Response to recent press."

Furthermore, universities like MIT, who entered into a subcontract with Nectome, are under pressure to seek funding through partnerships with industry as a result of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980. Also known as the Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act, this piece of legislation allows universities to commercialize inventions developed under federally funded research programs, like Nectome's method of preserving brains, formally called Aldehyde-Stabilized Cryopreservation.

"[Universities use] every incentive now to talk about innovation," explains Dr. Ivan Oransky, president of the Association of Health Care Journalists and co-founder of retractionwatch.com, a blog that catalogues errors and fraud in published research. "Innovation to me is often a fancy word for hype. The role of journalists should not be to glorify what universities [say, but to] tell the closest version of the truth they can."

In this case, a combination of the hyperbolic press, combined with some impressively researched expose pieces, led MIT to cut its ties with Nectome on April 2nd, 2018, just two weeks after the news of their company broke.

The solution to the dangers of hype, experts say, is a more scientifically literate public—and less clickbait-driven journalism.

Because of its multi-layered nature, science hype carries several disturbing consequences. For one, exaggerated coverage of a discovery could mislead the public by giving them false hope or unfounded worry. And media hype can contribute to a general mistrust of science. In these instances, people might, as Auch puts it, "fall back on previously held beliefs, evocative narratives, or comforting biases instead of well-justified scientific evidence."

All of this is especially dangerous in today's 'fake news' era, when companies or political parties sow public confusion for their own benefit, such as with global warming. In the case of Nectome, the danger is that people might opt to end their lives based off a lacking scientific theory. In fact, the company is hoping to enlist terminal patients in California, where doctor-assisted suicide is legal. And 25 people have paid the $10,000 to join Nectome's waiting list, including Sam Altman, president of the famed startup accelerator Y Combinator. Nectome now has offered to refund the money.

Founders McCanna and McIntyre did not return repeated requests for comment for this article. A new statement on their website begins: "Vitrifixation today is a powerful research tool, but needs more research and development before anyone considers applying it in a context other than research."

The solution to the dangers of hype, experts say, is a more scientifically literate public—and less clickbait-driven journalism. Until then, it seems that companies like Nectome will continue to enjoy at least 15 minutes of fame.

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

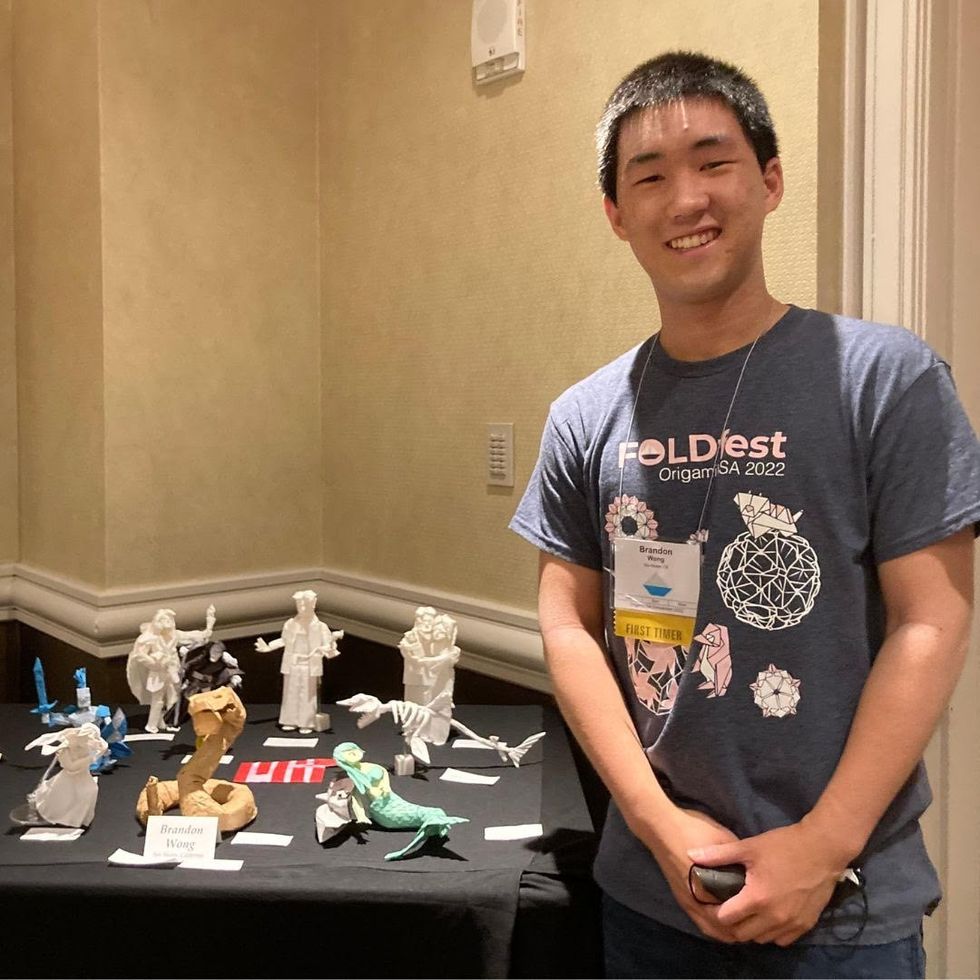

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”