The Death Predictor: A Helpful New Tool or an Ethical Morass?

A senior in hospice care.

Whenever Eric Karl Oermann has to tell a patient about a terrible prognosis, their first question is always: "how long do I have?" Oermann would like to offer a precise answer, to provide some certainty and help guide treatment. But although he's one of the country's foremost experts in medical artificial intelligence, Oermann is still dependent on a computer algorithm that's often wrong.

Doctors are notoriously terrible at guessing how long their patients will live.

Artificial intelligence, now often called deep learning or neural networks, has radically transformed language and image processing. It's allowed computers to play chess better than the world's grand masters and outwit the best Jeopardy players. But it still can't precisely tell a doctor how long a patient has left – or how to help that person live longer.

Someday, researchers predict, computers will be able to watch a video of a patient to determine their health status. Doctors will no longer have to spend hours inputting data into medical records. And computers will do a better job than specialists at identifying tiny tumors, impending crises, and, yes, figuring out how long the patient has to live. Oermann, a neurosurgeon at Mount Sinai, says all that technology will allow doctors to spend more time doing what they do best: talking with their patients. "I want to see more deep learning and computers in a clinical setting," he says, "so there can be more human interaction." But those days are still at least three to five years off, Oermann and other researchers say.

Doctors are notoriously terrible at guessing how long their patients will live, says Nigam Shah, an associate professor at Stanford University and assistant director of the school's Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. Doctors don't want to believe that their patient – whom they've come to like – will die. "Doctors over-estimate survival many-fold," Shah says. "How do you go into work, in say, oncology, and not be delusionally optimistic? You have to be."

But patients near the end of life will get better treatment – and even live longer – if they are overseen by hospice or palliative care, research shows. So, instead of relying on human bias to select those whose lives are nearing their end, Shah and his colleagues showed that they could use a deep learning algorithm based on medical records to flag incoming patients with a life expectancy of three months to a year. They use that data to indicate who might need palliative care. Then, the palliative care team can reach out to treating physicians proactively, instead of relying on their referrals or taking the time to read extensive medical charts.

But, although the system works well, Shah isn't yet sure if such indicators actually get the appropriate patients into palliative care. He's recently partnered with a palliative care doctor to run a gold-standard clinical trial to test whether patients who are flagged by this algorithm are indeed a better match for palliative care.

"What is effective from a health system perspective might not be effective from a treating physician's perspective and might not be effective from the patient's perspective," Shah notes. "I don't have a good way to guess everybody's reaction without actually studying it." Whether palliative care is appropriate, for instance, depends on more than just the patient's health status. "If the patient's not ready, the family's not ready and the doctor's not ready, then you're just banging your head against the wall," Shah says. "Given limited capacity, it's a waste of resources" to put that person in palliative care.

The algorithm isn't perfect, but "on balance, it leads to better decisions more often."

Alexander Smith and Sei Lee, both palliative care doctors, work together at the University of California, San Francisco, to develop predictions for patients who come to the hospital with a complicated prognosis or a history of decline. Their algorithm, they say, helps decide if this patient's problems – which might include diabetes, heart disease, a slow-growing cancer, and memory issues – make them eligible for hospice. The algorithm isn't perfect, they both agree, but "on balance, it leads to better decisions more often," Smith says.

Bethany Percha, an assistant professor at Mount Sinai, says that an algorithm may tell doctors that their patient is trending downward, but it doesn't do anything to change that trajectory. "Even if you can predict something, what can you do about it?" Algorithms may be able to offer treatment suggestions – but not what specific actions will alter a patient's future, says Percha, also the chief technology officer of Precise Health Enterprise, a product development group within Mount Sinai. And the algorithms remain challenging to develop. Electronic medical records may be great at her hospital, but if the patient dies at a different one, her system won't know. If she wants to be certain a patient has died, she has to merge social security records of death with her system's medical records – a time-consuming and cumbersome process.

An algorithm that learns from biased data will be biased, Shah says. Patients who are poor or African American historically have had worse health outcomes. If researchers train an algorithm on data that includes those biases, they get baked into the algorithms, which can then lead to a self-fulfilling prophesy. Smith and Lee say they've taken race out of their algorithms to avoid this bias.

Age is even trickier. There's no question that someone's risk of illness and death goes up with age. But an 85-year-old who breaks a hip running a marathon should probably be treated very differently than an 85-year-old who breaks a hip trying to get out of a chair in a dementia care unit. That's why the doctor can never be taken out of the equation, Shah says. Human judgment will always be required in medical care and an algorithm should never be followed blindly, he says.

Experts say that the flaws in artificial intelligence algorithms shouldn't prevent people from using them – carefully.

Researchers are also concerned that their algorithms will be used to ration care, or that insurance companies will use their data to justify a rate increase. If an algorithm predicts a patient is going to end up back in the hospital soon, "who's benefitting from knowing a patient is going to be readmitted? Probably the insurance company," Percha says.

Still, Percha and others say, the flaws in artificial intelligence algorithms shouldn't prevent people from using them – carefully. "These are new and exciting tools that have a lot of potential uses. We need to be conscious about how to use them going forward, but it doesn't mean we shouldn't go down this road," she says. "I think the potential benefits outweigh the risks, especially because we've barely scratched the surface of what big data can do right now."

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

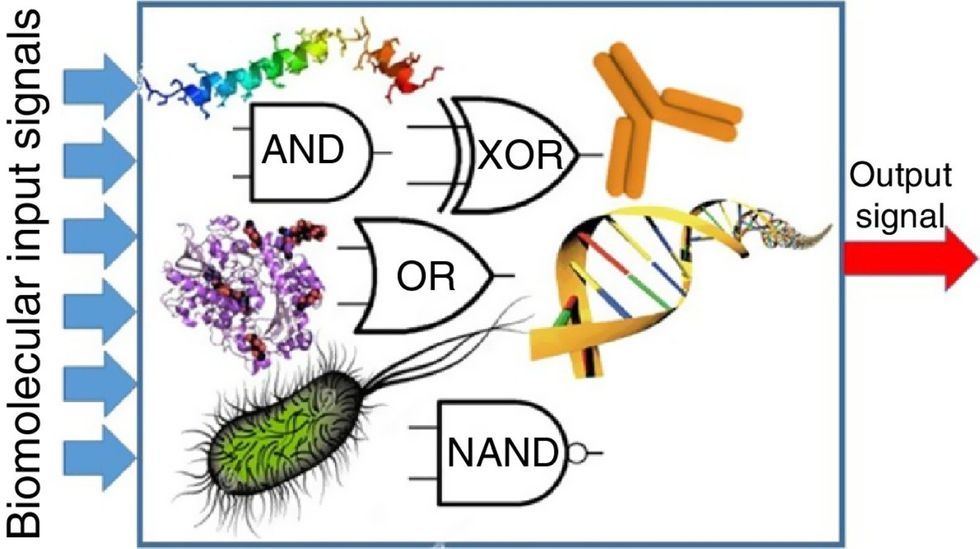

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.