The First Cloned Monkeys Provoked More Shrugs Than Shocks

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, the two cloned macaques.

A few months ago, it was announced that not one, but two healthy long-tailed macaque monkeys were cloned—a first for primates of any kind. The cells were sourced from aborted monkey fetuses and the DNA transferred into eggs whose nuclei had been removed, the same method that was used in 1996 to clone "Dolly the Sheep." Two live births, females named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, resulted from 60 surrogate mothers. Inefficient, it's true. But over time, the methods are likely to be improved.

The scientist who supervised the project predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening.

Dr. Gerald Schatten, a famous would-be monkey cloner, authored a controversial paper in 2003 describing the formidable challenges to cloning monkeys and humans, speculating that the feat might never be accomplished. Now, some 15 years later, that prediction, insofar as it relates to monkeys, has blown away.

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua were created at the Chinese Academy of Science's Institute of Neuroscience in Shanghai. The Institute founded in 1999 boasts 32 laboratories, expanding to 50 labs in 2020. It maintains two non-human primate research facilities.

The founder and director, Dr. Mu-ming Poo, supervised the project. Poo is an extremely accomplished senior researcher at the pinnacle of his field, a distinguished professor emeritus in Biology at UC Berkeley. In 2016, he was awarded the prestigious $500,000 Gruber Neuroscience Prize. At that time, Poo's experiments were described by a colleague as being "innovative and very often ingenious."

Poo maintains the reputation of studying some of the most important questions in cellular neuroscience.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans?

By Western standards, use of non-human primates in research focuses on the welfare of the animal subjects. As PETA reminds us, there is a dreadful and sad history of mistreatment. Dr. Poo assures us that his cloned monkeys are treated ethically and that the Institute is compliant with the highest regulatory standards, as promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

He presents the noblest justifications for the research. He predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening. He declares that this will eventually help to solve Parkinson's, Huntington's and Alzheimer's disease.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans? It appears so.

While much of the news coverage expressed this predictable worry, my overall impression is that the societal response was muted. Where was the expected outrage? Then again, we've come a long way since Dolly the Sheep in terms of both the science and the cultural acceptance of cloning. Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

I sometimes joke that I am the world's only human cloning lawyer—a great gig but there are still no clients.

I first crashed into the cloning scene in 2002 when I sued the so-called human cloning company "Clonaid" and asked in court to have a temporary guardian appointed for the alleged first human clone "Baby Eve." The claim needed to be tested, and mine was the first case ever aiming to protect the rights of a human clone. My legal basis was child welfare law, protecting minors from abuse, negligence, and exploitation.

The case had me on back-to-back global television broadcasts around the world; there was live news and "breathless" coverage at the courthouse emblazoned in headlines in every language on the planet. Cloning was, after all, perceived as a species-altering event: asexual reproduction. The controversy dominated world headlines for month until Clonaid's claim was busted as the "fakest" of fake news.

Fresh off the cloning case, the scientific community reached out to me, seeing me as the defender of legitimate science, an opponent of cloning human babies but a proponent of using cloning techniques to accelerate ethical regenerative medicine and embryonic stem cell research in general.

The years 2003 to 2006 were the era of the "stem cell wars" and a dominant issue was human cloning. Social conservative lawmakers around the world were seeking bans or criminalization not only of cloning babies but also the cloning of cells to match the donor's genetics. Scientists were being threatened with fines and imprisonment. Human cloning was being challenged in the United Nations with the United States backing a global treaty to ban and morally condemn all cloning -- including the technique that was crucial for research.

Scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

At the same time, scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

So my organization organized a conference at UN headquarters to defend research cloning and all the big names in stem cell research were there. We organized petitions to the UN and faxed 35,000 signatures to the country mission. These ongoing public policy battles were exacerbated in part because of the growing fear that cloning babies was just around the corner.

Then in 2005, the first cloned dog stunned the world, an Afghan hound named Snuppy. I met him when I visited the laboratories of Professor Woo Suk Hwang in Korea. His minders let me hold his leash -- TIME magazine's scientific breakthrough of the year. He didn't lick me or even wag his tail; I figured he must not like lawyers.

Tragically, soon thereafter, I witnessed firsthand Dr. Hwang's fall from grace when his human stem cell cloning breakthroughs proved false. The massive scientific misconduct rocked the nation of Korea, stem cell science in general, and provoked terrible news coverage.

Nevertheless, by 2007, the proposed bans lost steam, overridden by the advent of a Japanese researcher's Nobel Prize winning formula for reprogramming human cells to create genetically matched cell lines, not requiring the destruction of human embryos.

After years of panic, none of the recent cloning headlines has caused much of a stir.

Five years later, when two American scientists accomplished therapeutic human cloned stem cell lines, their news was accepted without hysteria. Perhaps enough time had passed since Hwang and the drama was drained.

In the just past 30 days we have seen more cloning headlines. Another cultural icon, Barbara Streisand, revealed she owns two cloned Coton de Tulear puppies. The other weekend, the television news show "60 Minutes" devoted close to an hour on the cloned ponies used at the top level of professional polo. And in India, scientists just cloned the first Assamese buffalo.

And you know what? After years of panic, none of this has caused much of a stir. It's as if the future described by Alvin Toffler in "Future Shock" has arrived and we are just living with it. A couple of cloned monkeys barely move the needle.

Perhaps it is the advent of the Internet and the overall dilution of wonder and outrage. Or maybe the muted response is rooted in popular culture. From Orphan Black to the plotlines of dozens of shows and books, cloning is just old news. The hand-wringing discussions about "human dignity" and "slippery slopes" have taken a backseat to the AI apocalypse and Martian missions.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed progress.

Personally, I still believe that cloned children should not be an option. Child welfare laws might be the best deterrent.

The same does not hold for cloning monkey research subjects. Squeamishness aside, I think Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua will soon be joined by a legion of cloned macaques and probably marmosets.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed the mending of these consciousness-destroying afflictions.

Scientific revolutions once took centuries, then decades, and now seem to bombard us daily. The convergence of technologies has accelerated the future. To Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, my best wishes with the hope that their sacrifices will contribute to the health of all primates -- not just humans.

Stacey Khoury felt more fatigued and out of breath than she was used to from just walking up the steps to her job in retail jewelry sales in Nashville, Tennessee. By the time she got home, she was more exhausted than usual, too.

"I just thought I was working too hard and needed more exercise," recalls the native Nashvillian about those days in December 2010. "All of the usual excuses you make when you're not feeling 100%."

As a professional gemologist, being hospitalized during peak holiday sales season wasn't particularly convenient. There was no way around it though when her primary care physician advised Khoury to see a blood disorder oncologist because of her disturbing blood count numbers. As part of a routine medical exam, a complete blood count screens for a variety of diseases and conditions that affect blood cells, such as anemia, infection, inflammation, bleeding disorders and cancer.

"If approved, it will allow more patients to potentially receive a transplant than would have gotten one before."

While she was in the hospital, a bone marrow biopsy revealed that Khoury had acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, a high-risk blood cancer. After Khoury completed an intense first round of chemotherapy, her oncologist recommended a bone marrow transplant. The potentially curative treatment for blood-cancer patients requires them to first receive a high dose of chemotherapy. Next, an infusion of stem cells from a healthy donor's bone marrow helps form new blood cells to fight off the cancer long-term.

Each year, approximately 8,000 patients in the U.S. with AML and other blood cancers receive a bone marrow transplant from a donor, according to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. But Khoury wasn't so lucky. She ended up being among the estimated 40% of patients eligible for bone marrow transplants who don't receive one, usually because there's no matched donor available.

Khoury's oncologist told her about another option. She could enter a clinical trial for an investigational cell therapy called omidubicel, which is being developed by Israeli biotech company Gamida Cell. The company's cell therapy, which is still experimental, could up a new avenue of treatment for cancer patients who can't get a bone marrow transplant.

Omidubicel consists of stem cells from cord blood that have been expanded using Gamida's technology to ensure there are enough cells for a therapeutic dose. The company's technology allows the immature cord blood cells to multiply quickly in the lab. Like a bone marrow transplant, the goal of the therapy is to make sure the donor cells make their way to the bone marrow and begin producing healthy new cells — a process called engraftment.

"If approved, it will allow more patients to potentially receive a transplant than would have gotten one before, so there's something very novel and exciting about that," says Ronit Simantov, Gamida Cell's chief medical officer.

Khoury and her husband Rick packed up their car and headed to the closest trial site, the Duke University School of Medicine, roughly 500 miles away. There they met with Mitchell Horowitz, a stem cell transplant specialist at Duke and principal investigator for Gamida's omidubicel study in the U.S.

He told Khoury she was a perfect candidate for the trial, and she enrolled immediately. "When you have one of two decisions, and it's either do this or you're probably not going to be around, it was a pretty easy decision to make, and I am truly thankful for that," she says.

Khoury's treatment started at the end of March 2011, and she was home by July 4 that year. She say the therapy "worked the way the doctors wanted it to work." Khoury's blood counts were rising quicker than the people who had bone marrow matches, and she was discharged from Duke earlier than other patients were.

By expanding the number of cord blood cells — which are typically too few to treat an adult — omidubicel allows doctors to use cord blood for patients who require a transplant but don't have a donor match for bone marrow.

Patients receiving omidubicel first get a blood test to determine their human leukocyte antigen, or HLA, type. This protein is found on most cells in the body and is an important regulator of the immune system. HLA typing is used to match patients to bone marrow and cord blood donors, but cord blood doesn't require as close of a match.

Like bone marrow transplants, one potential complication of omidubicel is graft-versus-host disease, when the donated bone marrow or stem cells register the recipient's body as foreign and attack the body. Depending on the severity of the response, according to the Mayo Clinic, treatment includes medication to suppress the immune system, such as steroids. In clinical trials, the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease with omidubicel was comparable with traditional bone marrow transplants.

"Transplant doctors are working on improving that," Simantov says. "A number of new therapies that specifically address graft-versus-host disease will be making some headway in the coming months and years."

Gamida released the results of the Phase 3 study in February and continues to follow Khoury and the other study patients for their long-term outcomes. The large randomized trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of omidubicel compared to standard umbilical cord blood transplants in patients with blood cancer who didn't have a suitable bone marrow donor. Around 120 patients aged 12 to 65 across the U.S., Europe and Asia were included in the trial. The study found that omidubicel resulted in faster recovery, fewer bacterial and viral infections and fewer days in the hospital.

The company plans to seek FDA approval this year. Simantov anticipates the therapy will receive FDA approval by 2022.

"Opening up cord blood transplants is very important, especially for people of diverse ethnic backgrounds," says oncologist Gary Schiller, principal investigator at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA for Gamida Cell's mid- and late-stage trials. "This expansion technology makes a big difference because it makes cord blood an available option for those who do not have another donor source."

As for Khoury, who proudly celebrated the anniversary of her first transplant in April—she remains cancer free and continues to work full-time as a gemologist. When she has a little free time, she enjoys gardening, sewing, or maybe traveling to national parks like Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon with her husband Rick.

Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

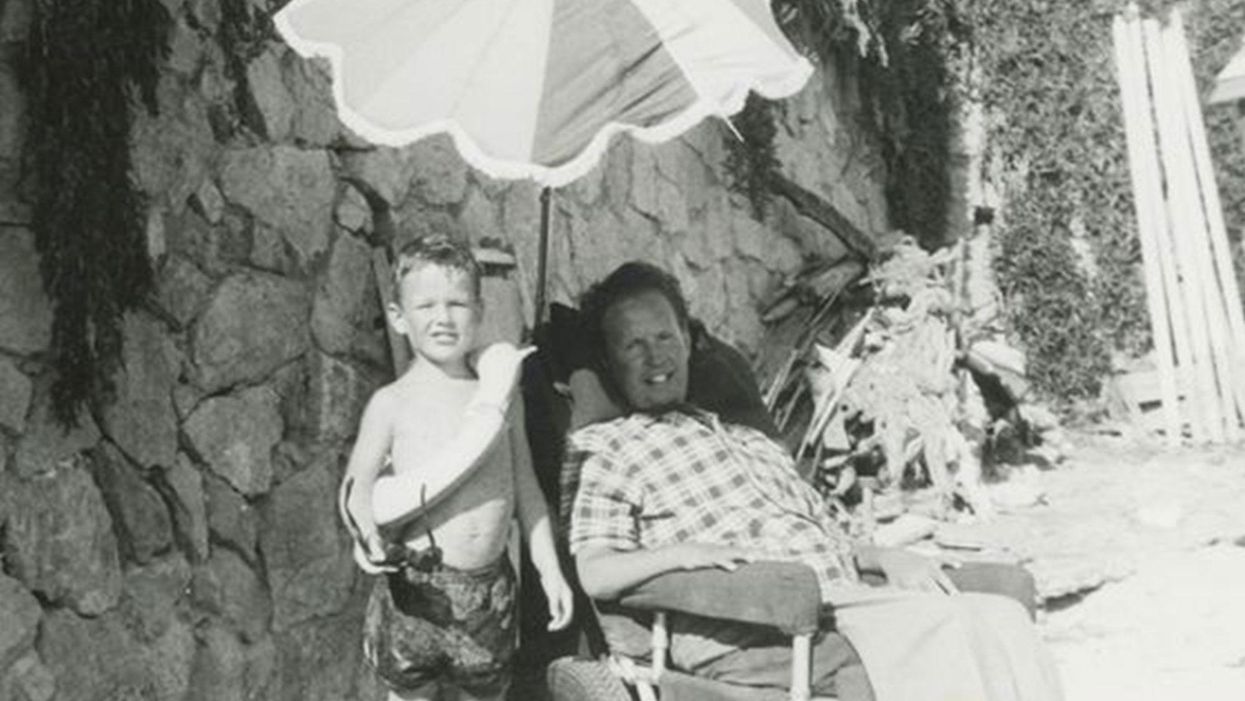

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.