The First Cloned Monkeys Provoked More Shrugs Than Shocks

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, the two cloned macaques.

A few months ago, it was announced that not one, but two healthy long-tailed macaque monkeys were cloned—a first for primates of any kind. The cells were sourced from aborted monkey fetuses and the DNA transferred into eggs whose nuclei had been removed, the same method that was used in 1996 to clone "Dolly the Sheep." Two live births, females named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, resulted from 60 surrogate mothers. Inefficient, it's true. But over time, the methods are likely to be improved.

The scientist who supervised the project predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening.

Dr. Gerald Schatten, a famous would-be monkey cloner, authored a controversial paper in 2003 describing the formidable challenges to cloning monkeys and humans, speculating that the feat might never be accomplished. Now, some 15 years later, that prediction, insofar as it relates to monkeys, has blown away.

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua were created at the Chinese Academy of Science's Institute of Neuroscience in Shanghai. The Institute founded in 1999 boasts 32 laboratories, expanding to 50 labs in 2020. It maintains two non-human primate research facilities.

The founder and director, Dr. Mu-ming Poo, supervised the project. Poo is an extremely accomplished senior researcher at the pinnacle of his field, a distinguished professor emeritus in Biology at UC Berkeley. In 2016, he was awarded the prestigious $500,000 Gruber Neuroscience Prize. At that time, Poo's experiments were described by a colleague as being "innovative and very often ingenious."

Poo maintains the reputation of studying some of the most important questions in cellular neuroscience.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans?

By Western standards, use of non-human primates in research focuses on the welfare of the animal subjects. As PETA reminds us, there is a dreadful and sad history of mistreatment. Dr. Poo assures us that his cloned monkeys are treated ethically and that the Institute is compliant with the highest regulatory standards, as promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

He presents the noblest justifications for the research. He predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening. He declares that this will eventually help to solve Parkinson's, Huntington's and Alzheimer's disease.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans? It appears so.

While much of the news coverage expressed this predictable worry, my overall impression is that the societal response was muted. Where was the expected outrage? Then again, we've come a long way since Dolly the Sheep in terms of both the science and the cultural acceptance of cloning. Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

I sometimes joke that I am the world's only human cloning lawyer—a great gig but there are still no clients.

I first crashed into the cloning scene in 2002 when I sued the so-called human cloning company "Clonaid" and asked in court to have a temporary guardian appointed for the alleged first human clone "Baby Eve." The claim needed to be tested, and mine was the first case ever aiming to protect the rights of a human clone. My legal basis was child welfare law, protecting minors from abuse, negligence, and exploitation.

The case had me on back-to-back global television broadcasts around the world; there was live news and "breathless" coverage at the courthouse emblazoned in headlines in every language on the planet. Cloning was, after all, perceived as a species-altering event: asexual reproduction. The controversy dominated world headlines for month until Clonaid's claim was busted as the "fakest" of fake news.

Fresh off the cloning case, the scientific community reached out to me, seeing me as the defender of legitimate science, an opponent of cloning human babies but a proponent of using cloning techniques to accelerate ethical regenerative medicine and embryonic stem cell research in general.

The years 2003 to 2006 were the era of the "stem cell wars" and a dominant issue was human cloning. Social conservative lawmakers around the world were seeking bans or criminalization not only of cloning babies but also the cloning of cells to match the donor's genetics. Scientists were being threatened with fines and imprisonment. Human cloning was being challenged in the United Nations with the United States backing a global treaty to ban and morally condemn all cloning -- including the technique that was crucial for research.

Scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

At the same time, scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

So my organization organized a conference at UN headquarters to defend research cloning and all the big names in stem cell research were there. We organized petitions to the UN and faxed 35,000 signatures to the country mission. These ongoing public policy battles were exacerbated in part because of the growing fear that cloning babies was just around the corner.

Then in 2005, the first cloned dog stunned the world, an Afghan hound named Snuppy. I met him when I visited the laboratories of Professor Woo Suk Hwang in Korea. His minders let me hold his leash -- TIME magazine's scientific breakthrough of the year. He didn't lick me or even wag his tail; I figured he must not like lawyers.

Tragically, soon thereafter, I witnessed firsthand Dr. Hwang's fall from grace when his human stem cell cloning breakthroughs proved false. The massive scientific misconduct rocked the nation of Korea, stem cell science in general, and provoked terrible news coverage.

Nevertheless, by 2007, the proposed bans lost steam, overridden by the advent of a Japanese researcher's Nobel Prize winning formula for reprogramming human cells to create genetically matched cell lines, not requiring the destruction of human embryos.

After years of panic, none of the recent cloning headlines has caused much of a stir.

Five years later, when two American scientists accomplished therapeutic human cloned stem cell lines, their news was accepted without hysteria. Perhaps enough time had passed since Hwang and the drama was drained.

In the just past 30 days we have seen more cloning headlines. Another cultural icon, Barbara Streisand, revealed she owns two cloned Coton de Tulear puppies. The other weekend, the television news show "60 Minutes" devoted close to an hour on the cloned ponies used at the top level of professional polo. And in India, scientists just cloned the first Assamese buffalo.

And you know what? After years of panic, none of this has caused much of a stir. It's as if the future described by Alvin Toffler in "Future Shock" has arrived and we are just living with it. A couple of cloned monkeys barely move the needle.

Perhaps it is the advent of the Internet and the overall dilution of wonder and outrage. Or maybe the muted response is rooted in popular culture. From Orphan Black to the plotlines of dozens of shows and books, cloning is just old news. The hand-wringing discussions about "human dignity" and "slippery slopes" have taken a backseat to the AI apocalypse and Martian missions.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed progress.

Personally, I still believe that cloned children should not be an option. Child welfare laws might be the best deterrent.

The same does not hold for cloning monkey research subjects. Squeamishness aside, I think Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua will soon be joined by a legion of cloned macaques and probably marmosets.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed the mending of these consciousness-destroying afflictions.

Scientific revolutions once took centuries, then decades, and now seem to bombard us daily. The convergence of technologies has accelerated the future. To Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, my best wishes with the hope that their sacrifices will contribute to the health of all primates -- not just humans.

A Rare Disease Just "Messed with the Wrong Mother." Now She's Fighting to Beat It Once and For All.

Amber Freed and Maxwell near their home in Denver, Colorado.

Amber Freed felt she was the happiest mother on earth when she gave birth to twins in March 2017. But that euphoric feeling began to fade over the next few months, as she realized her son wasn't making the same developmental milestones as his sister. "I had a perfect benchmark because they were twins, and I saw that Maxwell was floppy—he didn't have muscle tone and couldn't hold his neck up," she recalls. At first doctors placated her with statements that boys sometimes develop slower than girls, but the difference was just too drastic. At 10 month old, Maxwell had never reached to grab a toy. In fact, he had never even used his hands.

Thinking that perhaps Maxwell couldn't see well, Freed took him to an ophthalmologist who was the first to confirm her worst fears. He didn't find Maxwell to have vision problems, but he thought there was something wrong with the boy's brain. He had seen similar cases before and they always turned out to be rare disorders, and always fatal. "Start preparing yourself for your child not to live," he had said.

Getting the diagnosis took months of painful, invasive procedures, as well as fighting with the health insurance to get the genetic testing approved. Finally, in June 2018, doctors at the Children's Hospital Colorado gave the Freeds their son's diagnosis—a genetic mutation so rare it didn't even have a name, just a bunch of letters jammed together into a word SLC6A1—same as the name of the mutated gene. The mutation, with only 40 cases known worldwide at the time, caused developmental disabilities, movement and speech disorders, and a debilitating form of epilepsy.

The doctors didn't know much about the disorder, but they said that Maxwell would also regress in his development when he turned three or four. They couldn't tell how long he would live. "Hopefully you would become an expert and educate us about it," they said, as they gave Freed a five-page paper on the SLC6A1 and told her to start calling scientists if she wanted to help her son in any way. When she Googled the name, nothing came up. She felt horrified. "Our disease was too rare to care."

Freed's husband, a 6'2'' college football player broke down in sobs and she realized that if anything could be done to help Maxwell, she'd have be the one to do it. "I understood that I had to fight like a mother," she says. "And a determined mother can do a lot of things."

The Freed family.

Courtesy Amber Freed

She quit her job as an equity analyst the day of the diagnosis and became a full-time SLC6A1 citizen scientist looking for researchers studying mutations of this gene. In the wee hours of the morning, she called scientists in Europe. As the day progressed, she called researchers on the East Coast, followed by the West in the afternoon. In the evening, she switched to Asia and Australia. She asked them the same question. "Can you help explain my gene and how do we fix it?"

Scientists need money to do research, so Freed launched Milestones for Maxwell fundraising campaign, and a SLC6A1 Connect patient advocacy nonprofit, dedicated to improving the lives of children and families battling this rare condition. And then it became clear that the mutation wasn't as rare as it seemed. As other parents began to discover her nonprofit, the number of known cases rose from 40 to 100, and later to 400, Freed says. "The disease is only rare until it messes with the wrong mother."

It took one mother to find another to start looking into what's happening inside Maxwell's brain. Freed came across Jeanne Paz, a Gladstone Institutes researcher who studies epilepsy with particular interest in absence or silent seizures—those that don't manifest by convulsions, but rather make patients absently stare into space—and that's one type of seizures Maxwell has. "It's like a brief period of silence in the brain during which the person doesn't pay attention to what's happening, and as soon as they come out of the seizure they are back to life," Paz explains. "It's like a pause button on consciousness." She was working to understand the underlying biology.

To understand how seizures begin, spread and stop, Paz uses optogenetics in mice. From words "genetic" and "optikós," which means visible in Greek, the optogenetics technique involves two steps. First, scientists introduce a light-sensitive gene into a specific brain cell type—for example into excitatory neurons that release glutamate, a neurotransmitter, which activates other cells in the brain. Then they implant a very thin optical fiber into the brain area where they forged these light-sensitive neurons. As they shine the light through the optical fiber, researchers can make excitatory neurons to release glutamate—or instead tell them to stop being active and "shut up". The ability to control what these neurons of interest do, quite literally sheds light onto where seizures start, how they propagate and what cells are involved in stopping them.

"Let's say a seizure started and we shine the light that reduces the activity of specific neurons," Paz explains. "If that stops the seizure, we know that activating those cells was necessary to maintain the seizure." Likewise, shutting down their activity will make the seizure stop.

Freed reached out to Paz in 2019 and the two women had an instant connection. They were both passionate about brain and seizures research, even if for different reasons. Freed asked Paz if she would study her son's seizures and Paz agreed.

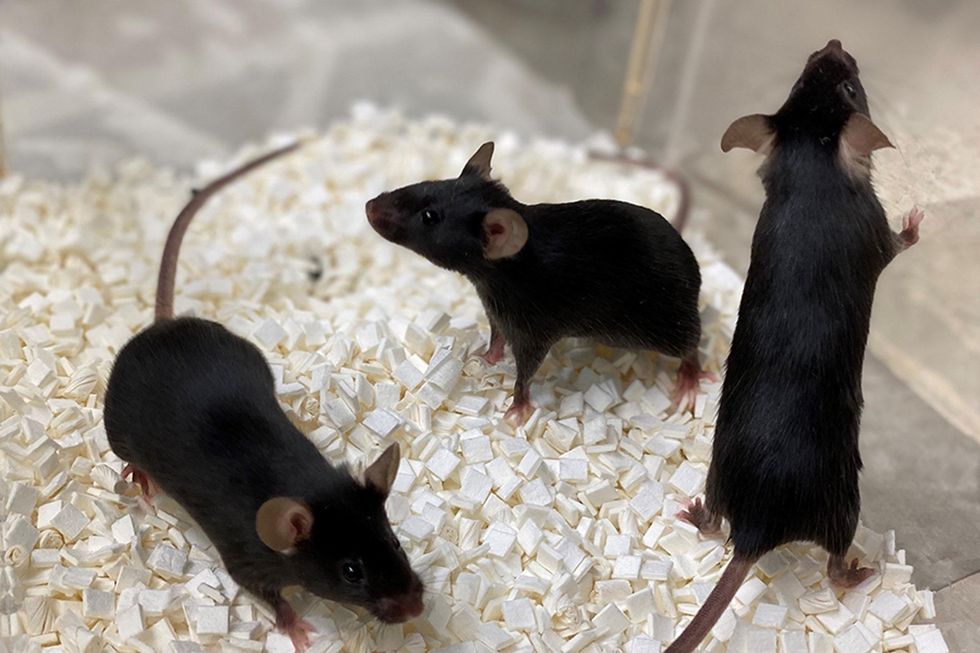

To do that, Paz needed mice that carried the SLC6A1 mutation, so Freed found a company in China that created them to specs. The company replaced a mouse SLC6A1 gene with a human mutated one and shipped them over to Paz's lab. "We call them Maxwell mice," Paz says, "and we are now implanting electrodes into them to see which brain regions generate seizures." That would help them understand what goes wrong and what brain cells are malfunctioning in the SLC6A1 mice—and help scientists better understand what might cause seizures in children.

Bred to carry SLC6A1 mutation, these "Maxwell mice" will help better understand this debilitating genetic disease. (These mice are from Vanderbilt University, where researchers are also studying SLC6A1.)

Courtesy Amber Freed

This information—along with other research Amber is funding in other institutions—will inform the development of a novel genetic treatment, in which scientists would deploy a harmless virus to deliver a healthy, working copy of the SLC6A1 gene into the mice brains. They would likely deliver the therapeutic via a spinal tap infusion, and if it works and doesn't produce side effects in mice, the human trials will follow.

In the meantime, Freed is raising money to fund other research of various stop-gap measures. On April 22, 2021, she updated her Milestone for Maxwell page with a post that her nonprofit is funding yet another effort. It is a trial at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, in which doctors will use an already FDA-approved drug, which was recently repurposed for the SLC6A1 condition to treat epilepsy in these children. "It will buy us time," Freed says—while the gene therapy effort progresses.

Freed is determined to beat SLC6A1 before it beats down her family. She hopes to put an end to this disease—and similar genetic diseases—once and for all. Her goal is not only to have scientists create a remedy, but also to add the mutation to a newborn screening panel. That way, children born with this condition in the future would receive gene therapy before they even leave the hospital.

"I don't want there to be another Maxwell Freed," she says, "and that's why I am fighting like a mother." The gene therapy trial still might be a few years away, but the Weill Cornell one aims to launch very soon—possibly around Mother's Day. This is yet another milestone for Maxwell, another baby step forward—and the best gift a mother can get.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

On May 13th, scientific and medical experts will discuss and answer questions about the vaccine for those under 16.

This virtual event convened leading scientific and medical experts to address the public's questions and concerns about Covid-19 vaccines in kids and teens. Highlight video below.

DATE:

Thursday, May 13th, 2021

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. EDT

Dr. H. Dele Davies, M.D., MHCM

Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Dean for Graduate Studies at the University of Nebraska Medical (UNMC). He is an internationally recognized expert in pediatric infectious diseases and a leader in community health.

Dr. Emily Oster, Ph.D.

Professor of Economics at Brown University. She is a best-selling author and parenting guru who has pioneered a method of assessing school safety.

Dr. Tina Q. Tan, M.D.

Professor of Pediatrics at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. She has been involved in several vaccine survey studies that examine the awareness, acceptance, barriers and utilization of recommended preventative vaccines.

Dr. Inci Yildirim, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc.

Associate Professor of Pediatrics (Infectious Disease); Medical Director, Transplant Infectious Diseases at Yale School of Medicine; Associate Professor of Global Health, Yale Institute for Global Health. She is an investigator for the multi-institutional COVID-19 Prevention Network's (CoVPN) Moderna mRNA-1273 clinical trial for children 6 months to 12 years of age.

About the Event Series

This event is the second of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.