The First Cloned Monkeys Provoked More Shrugs Than Shocks

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, the two cloned macaques.

A few months ago, it was announced that not one, but two healthy long-tailed macaque monkeys were cloned—a first for primates of any kind. The cells were sourced from aborted monkey fetuses and the DNA transferred into eggs whose nuclei had been removed, the same method that was used in 1996 to clone "Dolly the Sheep." Two live births, females named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, resulted from 60 surrogate mothers. Inefficient, it's true. But over time, the methods are likely to be improved.

The scientist who supervised the project predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening.

Dr. Gerald Schatten, a famous would-be monkey cloner, authored a controversial paper in 2003 describing the formidable challenges to cloning monkeys and humans, speculating that the feat might never be accomplished. Now, some 15 years later, that prediction, insofar as it relates to monkeys, has blown away.

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua were created at the Chinese Academy of Science's Institute of Neuroscience in Shanghai. The Institute founded in 1999 boasts 32 laboratories, expanding to 50 labs in 2020. It maintains two non-human primate research facilities.

The founder and director, Dr. Mu-ming Poo, supervised the project. Poo is an extremely accomplished senior researcher at the pinnacle of his field, a distinguished professor emeritus in Biology at UC Berkeley. In 2016, he was awarded the prestigious $500,000 Gruber Neuroscience Prize. At that time, Poo's experiments were described by a colleague as being "innovative and very often ingenious."

Poo maintains the reputation of studying some of the most important questions in cellular neuroscience.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans?

By Western standards, use of non-human primates in research focuses on the welfare of the animal subjects. As PETA reminds us, there is a dreadful and sad history of mistreatment. Dr. Poo assures us that his cloned monkeys are treated ethically and that the Institute is compliant with the highest regulatory standards, as promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

He presents the noblest justifications for the research. He predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening. He declares that this will eventually help to solve Parkinson's, Huntington's and Alzheimer's disease.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans? It appears so.

While much of the news coverage expressed this predictable worry, my overall impression is that the societal response was muted. Where was the expected outrage? Then again, we've come a long way since Dolly the Sheep in terms of both the science and the cultural acceptance of cloning. Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

I sometimes joke that I am the world's only human cloning lawyer—a great gig but there are still no clients.

I first crashed into the cloning scene in 2002 when I sued the so-called human cloning company "Clonaid" and asked in court to have a temporary guardian appointed for the alleged first human clone "Baby Eve." The claim needed to be tested, and mine was the first case ever aiming to protect the rights of a human clone. My legal basis was child welfare law, protecting minors from abuse, negligence, and exploitation.

The case had me on back-to-back global television broadcasts around the world; there was live news and "breathless" coverage at the courthouse emblazoned in headlines in every language on the planet. Cloning was, after all, perceived as a species-altering event: asexual reproduction. The controversy dominated world headlines for month until Clonaid's claim was busted as the "fakest" of fake news.

Fresh off the cloning case, the scientific community reached out to me, seeing me as the defender of legitimate science, an opponent of cloning human babies but a proponent of using cloning techniques to accelerate ethical regenerative medicine and embryonic stem cell research in general.

The years 2003 to 2006 were the era of the "stem cell wars" and a dominant issue was human cloning. Social conservative lawmakers around the world were seeking bans or criminalization not only of cloning babies but also the cloning of cells to match the donor's genetics. Scientists were being threatened with fines and imprisonment. Human cloning was being challenged in the United Nations with the United States backing a global treaty to ban and morally condemn all cloning -- including the technique that was crucial for research.

Scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

At the same time, scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

So my organization organized a conference at UN headquarters to defend research cloning and all the big names in stem cell research were there. We organized petitions to the UN and faxed 35,000 signatures to the country mission. These ongoing public policy battles were exacerbated in part because of the growing fear that cloning babies was just around the corner.

Then in 2005, the first cloned dog stunned the world, an Afghan hound named Snuppy. I met him when I visited the laboratories of Professor Woo Suk Hwang in Korea. His minders let me hold his leash -- TIME magazine's scientific breakthrough of the year. He didn't lick me or even wag his tail; I figured he must not like lawyers.

Tragically, soon thereafter, I witnessed firsthand Dr. Hwang's fall from grace when his human stem cell cloning breakthroughs proved false. The massive scientific misconduct rocked the nation of Korea, stem cell science in general, and provoked terrible news coverage.

Nevertheless, by 2007, the proposed bans lost steam, overridden by the advent of a Japanese researcher's Nobel Prize winning formula for reprogramming human cells to create genetically matched cell lines, not requiring the destruction of human embryos.

After years of panic, none of the recent cloning headlines has caused much of a stir.

Five years later, when two American scientists accomplished therapeutic human cloned stem cell lines, their news was accepted without hysteria. Perhaps enough time had passed since Hwang and the drama was drained.

In the just past 30 days we have seen more cloning headlines. Another cultural icon, Barbara Streisand, revealed she owns two cloned Coton de Tulear puppies. The other weekend, the television news show "60 Minutes" devoted close to an hour on the cloned ponies used at the top level of professional polo. And in India, scientists just cloned the first Assamese buffalo.

And you know what? After years of panic, none of this has caused much of a stir. It's as if the future described by Alvin Toffler in "Future Shock" has arrived and we are just living with it. A couple of cloned monkeys barely move the needle.

Perhaps it is the advent of the Internet and the overall dilution of wonder and outrage. Or maybe the muted response is rooted in popular culture. From Orphan Black to the plotlines of dozens of shows and books, cloning is just old news. The hand-wringing discussions about "human dignity" and "slippery slopes" have taken a backseat to the AI apocalypse and Martian missions.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed progress.

Personally, I still believe that cloned children should not be an option. Child welfare laws might be the best deterrent.

The same does not hold for cloning monkey research subjects. Squeamishness aside, I think Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua will soon be joined by a legion of cloned macaques and probably marmosets.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed the mending of these consciousness-destroying afflictions.

Scientific revolutions once took centuries, then decades, and now seem to bombard us daily. The convergence of technologies has accelerated the future. To Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, my best wishes with the hope that their sacrifices will contribute to the health of all primates -- not just humans.

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

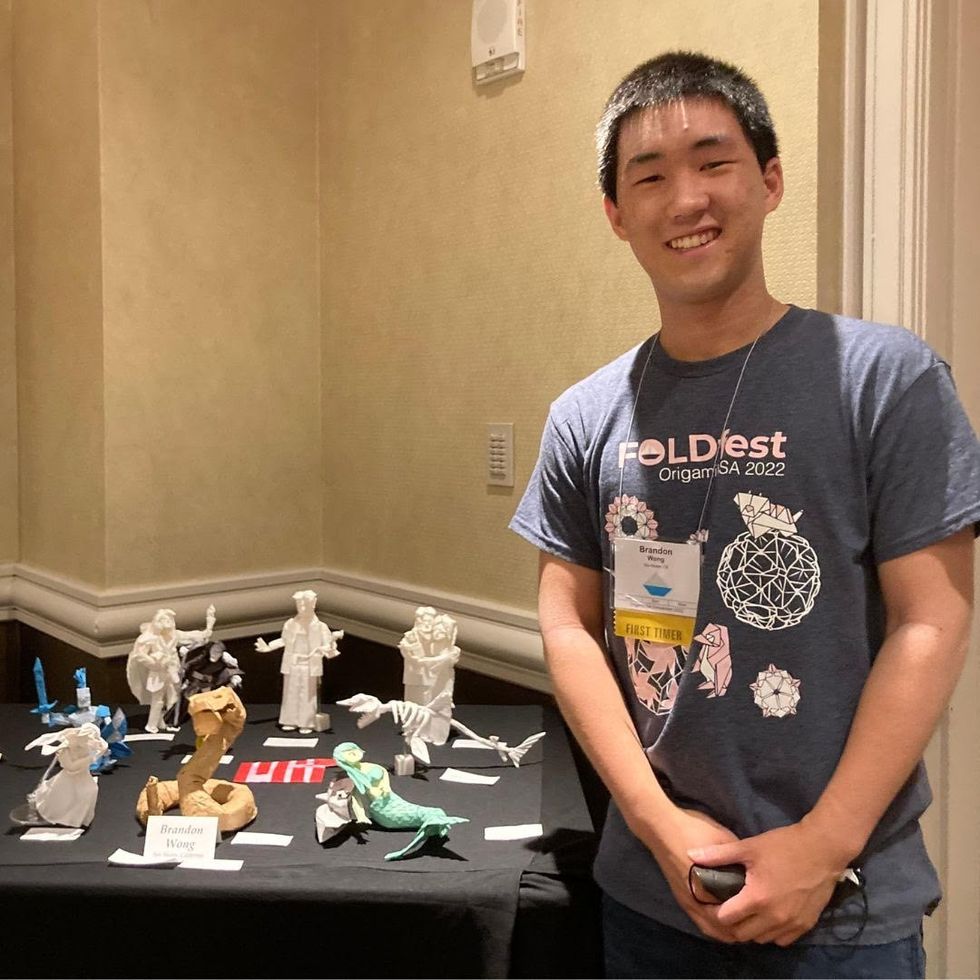

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”