The First Cloned Monkeys Provoked More Shrugs Than Shocks

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, the two cloned macaques.

A few months ago, it was announced that not one, but two healthy long-tailed macaque monkeys were cloned—a first for primates of any kind. The cells were sourced from aborted monkey fetuses and the DNA transferred into eggs whose nuclei had been removed, the same method that was used in 1996 to clone "Dolly the Sheep." Two live births, females named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, resulted from 60 surrogate mothers. Inefficient, it's true. But over time, the methods are likely to be improved.

The scientist who supervised the project predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening.

Dr. Gerald Schatten, a famous would-be monkey cloner, authored a controversial paper in 2003 describing the formidable challenges to cloning monkeys and humans, speculating that the feat might never be accomplished. Now, some 15 years later, that prediction, insofar as it relates to monkeys, has blown away.

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua were created at the Chinese Academy of Science's Institute of Neuroscience in Shanghai. The Institute founded in 1999 boasts 32 laboratories, expanding to 50 labs in 2020. It maintains two non-human primate research facilities.

The founder and director, Dr. Mu-ming Poo, supervised the project. Poo is an extremely accomplished senior researcher at the pinnacle of his field, a distinguished professor emeritus in Biology at UC Berkeley. In 2016, he was awarded the prestigious $500,000 Gruber Neuroscience Prize. At that time, Poo's experiments were described by a colleague as being "innovative and very often ingenious."

Poo maintains the reputation of studying some of the most important questions in cellular neuroscience.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans?

By Western standards, use of non-human primates in research focuses on the welfare of the animal subjects. As PETA reminds us, there is a dreadful and sad history of mistreatment. Dr. Poo assures us that his cloned monkeys are treated ethically and that the Institute is compliant with the highest regulatory standards, as promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

He presents the noblest justifications for the research. He predicts that cloning, along with gene editing, will result in "ideal primate models" for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening. He declares that this will eventually help to solve Parkinson's, Huntington's and Alzheimer's disease.

But is society ready to accept cloned primates for medical research without the attendant hysteria about fears of cloned humans? It appears so.

While much of the news coverage expressed this predictable worry, my overall impression is that the societal response was muted. Where was the expected outrage? Then again, we've come a long way since Dolly the Sheep in terms of both the science and the cultural acceptance of cloning. Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

Perhaps my unique vantage point can provide perspective on how much attitudes have evolved.

I sometimes joke that I am the world's only human cloning lawyer—a great gig but there are still no clients.

I first crashed into the cloning scene in 2002 when I sued the so-called human cloning company "Clonaid" and asked in court to have a temporary guardian appointed for the alleged first human clone "Baby Eve." The claim needed to be tested, and mine was the first case ever aiming to protect the rights of a human clone. My legal basis was child welfare law, protecting minors from abuse, negligence, and exploitation.

The case had me on back-to-back global television broadcasts around the world; there was live news and "breathless" coverage at the courthouse emblazoned in headlines in every language on the planet. Cloning was, after all, perceived as a species-altering event: asexual reproduction. The controversy dominated world headlines for month until Clonaid's claim was busted as the "fakest" of fake news.

Fresh off the cloning case, the scientific community reached out to me, seeing me as the defender of legitimate science, an opponent of cloning human babies but a proponent of using cloning techniques to accelerate ethical regenerative medicine and embryonic stem cell research in general.

The years 2003 to 2006 were the era of the "stem cell wars" and a dominant issue was human cloning. Social conservative lawmakers around the world were seeking bans or criminalization not only of cloning babies but also the cloning of cells to match the donor's genetics. Scientists were being threatened with fines and imprisonment. Human cloning was being challenged in the United Nations with the United States backing a global treaty to ban and morally condemn all cloning -- including the technique that was crucial for research.

Scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

At the same time, scientists and patients were touting the cloning technique as a major biomedical breakthrough because cells could be created as direct genetic matches from a specific donor.

So my organization organized a conference at UN headquarters to defend research cloning and all the big names in stem cell research were there. We organized petitions to the UN and faxed 35,000 signatures to the country mission. These ongoing public policy battles were exacerbated in part because of the growing fear that cloning babies was just around the corner.

Then in 2005, the first cloned dog stunned the world, an Afghan hound named Snuppy. I met him when I visited the laboratories of Professor Woo Suk Hwang in Korea. His minders let me hold his leash -- TIME magazine's scientific breakthrough of the year. He didn't lick me or even wag his tail; I figured he must not like lawyers.

Tragically, soon thereafter, I witnessed firsthand Dr. Hwang's fall from grace when his human stem cell cloning breakthroughs proved false. The massive scientific misconduct rocked the nation of Korea, stem cell science in general, and provoked terrible news coverage.

Nevertheless, by 2007, the proposed bans lost steam, overridden by the advent of a Japanese researcher's Nobel Prize winning formula for reprogramming human cells to create genetically matched cell lines, not requiring the destruction of human embryos.

After years of panic, none of the recent cloning headlines has caused much of a stir.

Five years later, when two American scientists accomplished therapeutic human cloned stem cell lines, their news was accepted without hysteria. Perhaps enough time had passed since Hwang and the drama was drained.

In the just past 30 days we have seen more cloning headlines. Another cultural icon, Barbara Streisand, revealed she owns two cloned Coton de Tulear puppies. The other weekend, the television news show "60 Minutes" devoted close to an hour on the cloned ponies used at the top level of professional polo. And in India, scientists just cloned the first Assamese buffalo.

And you know what? After years of panic, none of this has caused much of a stir. It's as if the future described by Alvin Toffler in "Future Shock" has arrived and we are just living with it. A couple of cloned monkeys barely move the needle.

Perhaps it is the advent of the Internet and the overall dilution of wonder and outrage. Or maybe the muted response is rooted in popular culture. From Orphan Black to the plotlines of dozens of shows and books, cloning is just old news. The hand-wringing discussions about "human dignity" and "slippery slopes" have taken a backseat to the AI apocalypse and Martian missions.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed progress.

Personally, I still believe that cloned children should not be an option. Child welfare laws might be the best deterrent.

The same does not hold for cloning monkey research subjects. Squeamishness aside, I think Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua will soon be joined by a legion of cloned macaques and probably marmosets.

We humans are enduring plagues of dementia and Alzheimer's, and we will need more monkeys. I will take mine cloned, if it will speed the mending of these consciousness-destroying afflictions.

Scientific revolutions once took centuries, then decades, and now seem to bombard us daily. The convergence of technologies has accelerated the future. To Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, my best wishes with the hope that their sacrifices will contribute to the health of all primates -- not just humans.

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

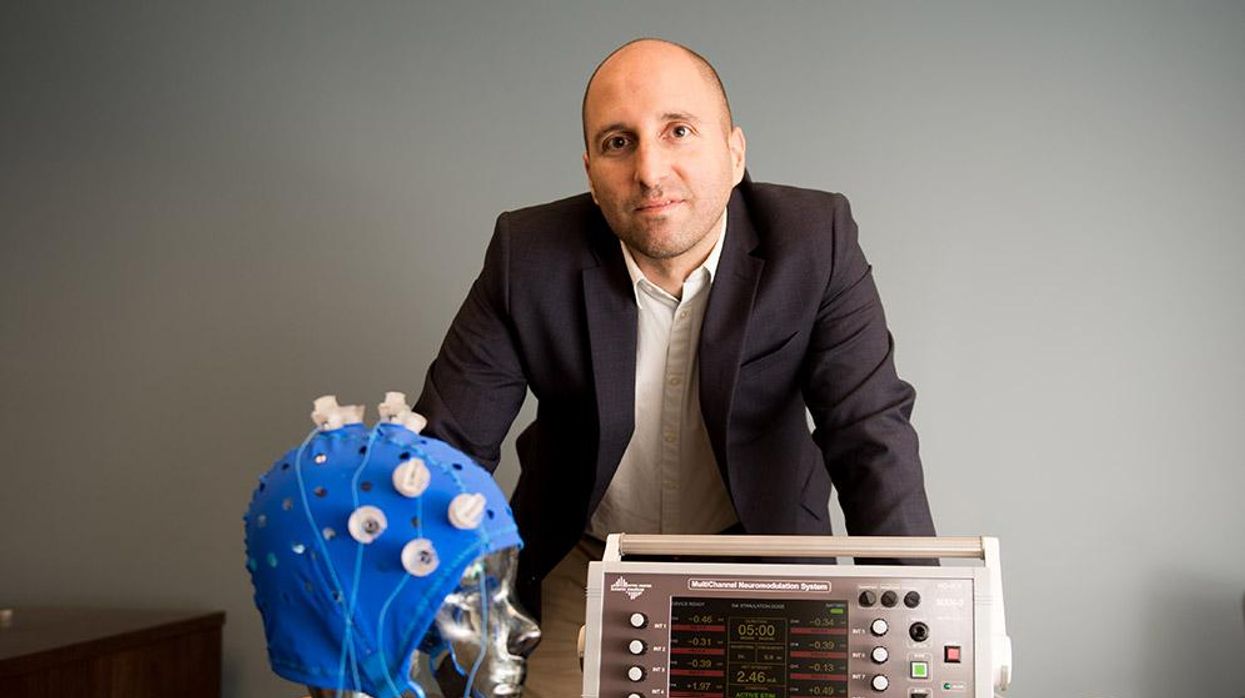

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”