The Only Hydroxychloroquine Story You Need to Read

Dr. Adalja is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. He has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and the system of care for infectious disease emergencies, and as an external advisor to the New York City Health and Hospital Emergency Management Highly Infectious Disease training program, as well as on a FEMA working group on nuclear disaster recovery. Dr. Adalja is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security. He was a coeditor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine, the Emergency Medicine CorePendium, Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple, UpToDate's section on biological terrorism, and a NATO volume on bioterrorism. He has also published in such journals as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Annals of Emergency Medicine. He is a board-certified physician in internal medicine, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. Follow him on Twitter: @AmeshAA

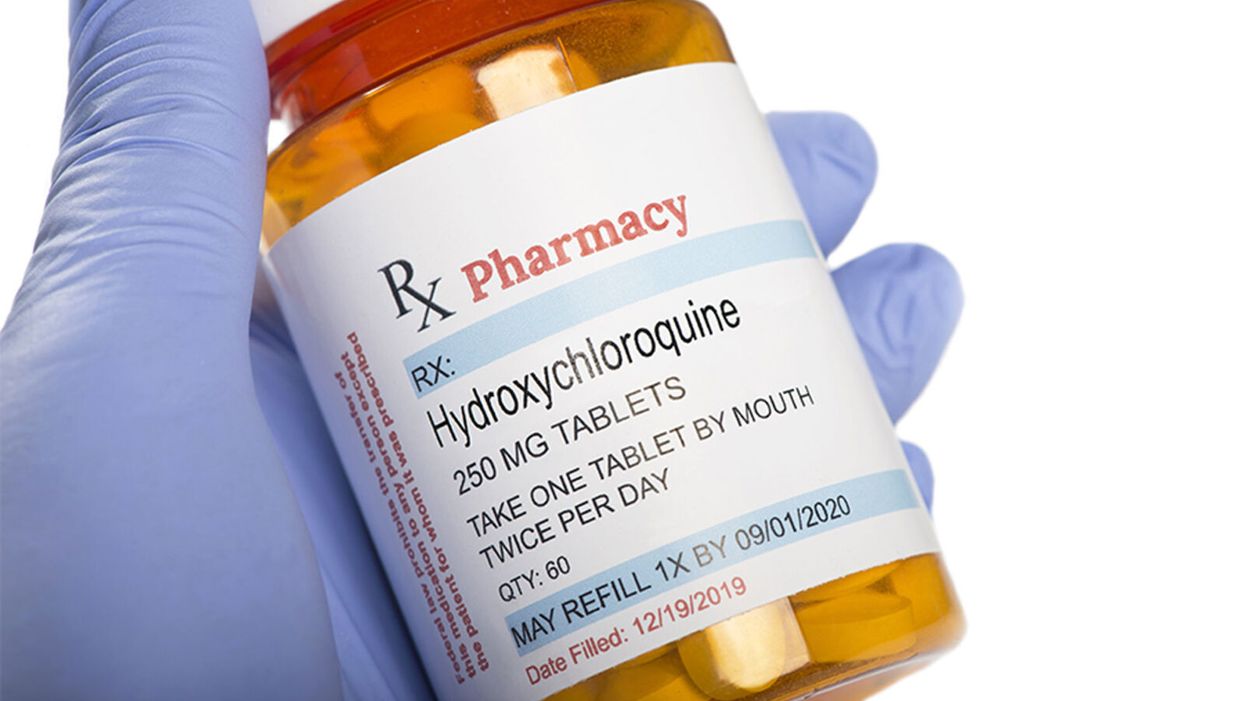

Hydroxychloroquine has been shown not to provide benefit for COVID-19 patients in multiple randomized controlled trials, despite continuous misinformation asserting its alleged effectiveness.

In the early days of a pandemic caused by a virus with no existing treatments, many different compounds are often considered and tried in an attempt to help patients.

It all relates back to a profound question: How do we know what we know?

Many of these treatments fall by the wayside as evidence accumulates regarding actual efficacy. At that point, other treatments become standard of care once their benefit is proven in rigorously designed trials.

However, about seven months into the pandemic, we're still seeing political resurrection of a treatment that has been systematically studied and demonstrated in well-designed randomized controlled trials to not have benefit.

The hydroxychloroquine (and by extension chloroquine) story is a complicated one that was difficult to follow even before it became infused with politics. It is a simple fact that these drugs, long approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), work in Petri dishes against various viruses including coronaviruses. This set of facts provided biological plausibility to support formally studying their use in the clinical treatment and prevention of COVID-19. As evidence from these studies accumulates, it is a cognitive requirement to integrate that knowledge and not to evade it. This also means evaluating the rigor of the studies.

In recent days we have seen groups yet again promoting the use of hydroxychloroquine in, what is to me, a baffling disregard of the multiple recent studies that have shown no benefit. Indeed, though FDA-approved for other indications like autoimmune conditions and preventing malaria, the emergency use authorization for COVID-19 has been rescinded (which means the government cannot stockpile it). Still, however, many patients continue to ask for the drug, compelled by political commentary, viral videos, and anecdotal data. Yet most doctors (like myself) are refusing to write the prescriptions outside of a clinical trial – a position endorsed by professional medical organizations such as the American College of Physicians and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Why this disconnect?

It all relates back to a profound question: How do we know what we know? In science, we use the scientific method – the process of observing reality, coming up with a hypothesis about what might be true, and testing that hypothesis as thoroughly as possible until we discover the objective truth.

The confusion we're seeing now stems from an inability to distinguish between anecdotes reported by physicians (observational data) and an actual evidence base. This is understandable among the general public but when done by a healthcare professional, it reveals a disdain for reason, logic, and the scientific method.

The Difference Between Observational Data and Randomized Controlled Trials

The power of informal observation is crucial. It is part of the scientific method but primarily as a basis for generating hypotheses that we can test. How do we conduct medical tests? The gold standard is the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. This means that neither the researchers nor the volunteers know who is getting a drug and who is getting a sugar pill. Then both groups of the trial, called arms, can be compared to determine whether the people who got the drug fared better. This study design prevents biases and the placebo effect from confounding the data and undermining the veracity of the results.

For example, a seemingly beneficial effect might be seen in an observational study with no blinding and no control group. In such a case, all patients are openly given the drug and their doctors observe how they do. A prime example is the 36-patient single-arm study from France that generated a tremendous amount of interest after President Trump tweeted about it. But this kind of a study by its nature cannot answer the critical question: Was the positive effect because of hydroxychloroquine or just the natural course of the illness? In other words, would someone have recovered in a similar fashion regardless of the drug? What is the role of the placebo effect?

These are reasons why it is crucial to give a placebo to a control group that is as similar in every respect as possible to those receiving the intervention. Then we attempt to find out by comparing the two groups: What is the side effect profile of the drug? Are the groups large enough to detect a relatively rare safety concern? How long were the patients followed for? Was something else responsible for making the patients get better, such as the use of steroids (as likely was the case in the Henry Ford study)?

Looking at the two major hydroxychloroquine trials, it is apparent that, when studied using the best tools of clinical trials, no benefit is likely to occur.

All of these considerations amount to just a fraction of the questions that can be answered more definitively in a well-designed large randomized controlled trial than in observational studies. Indeed, an observational study from New York failed to show any benefit in hospitalized patients, showing how unclear and disparate the results can be with these types of studies. A New York retrospective study (which examined patient outcomes after they were already treated) had similar results and included the use of azithromycin.

When evaluating a study, it is also important to note whether conflicts of interest exist, as well as the quality of the peer review and the data itself. In the case of the French study, for example, the paper was published in a journal in which one of the authors was editor-in-chief, and it was accepted for publication after 24 hours. Patients who fared poorly on hydroxychloroquine were also left out of the study altogether, skewing the results.

What Randomized Controlled Trials Have Shown

Looking at the two major hydroxychloroquine trials, it is apparent that, when studied using the best tools of clinical trials, no benefit is likely to occur. The most important of these studies to announce results was part of the Recovery trial, which was designed to test multiple interventions in the treatment of COVID-19. This trial, which has yet to be formally published, was a randomized controlled trial that involved over 1500 hospitalized patients being administered hydroxychloroquine compared to over 3000 who did not receive the medication. Clinical testing requires large numbers of patients to have the power to demonstrate statistical significance -- the threshold at which any apparent benefit is more than you would expect by random chance alone.

In this study, hydroxychloroquine provided no mortality benefit or even a benefit in hospital length of stay. In fact, the opposite occurred. Hydroxychloroquine patients were more likely to stay in the hospital longer and were more likely to require mechanical ventilation. Additionally, smaller randomized trials conducted in China have not shown benefit either.

Another major study involved the use of hydroxychloroquine to prevent illness in people who were exposed to COVID-19. These results, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, included over 800 patients who were studied in a randomized double-blind controlled trial and also failed to show any benefit.

But what about adding the antibiotic azithromycin in conjunction with hydroxychloroquine? A three-arm randomized controlled study involving over 500 patients hospitalized with mild to moderate COVID-19 was conducted. Its results, also published in The New England Journal of Medicine, failed to show any benefit – with or without azithromycin – and demonstrated evidence of harm. Those who received these treatments had elevations of their liver function tests and heart rhythm abnormalities. These findings hold despite the retraction of an observational study showing similar results.

Additionally, when used in combination with remdesivir – an experimental antiviral – hydroxychloroquine has been shown to be associated with worse outcomes and more side effects.

But what about in mildly ill patients not requiring hospitalization? There was no benefit found in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 400 patients, the majority of whom were given the drug within one day of symptoms.

Some randomized controlled studies have yet to report their findings on hydroxychloroquine in non-hospitalized patients, with the use of zinc (which has some evidence in the treatment of the common cold, another ailment that can be caused by coronaviruses). And studies have yet to come out regarding whether hydroxychloroquine can prevent people from getting sick before they are even exposed. But the preponderance of the evidence from studies designed specifically to find benefit for treating COVID-19 does not support its use outside of a research setting.

Today – even with some studies (including those with zinc) still ongoing – if a patient asked me to prescribe them hydroxychloroquine for any severity or stage of illness, with or without zinc, with or without azithromycin, I would refrain. I would explain that, based on the evidence from clinical trials that has been amassed, there is no reason to believe that it will alter the course of illness for the better.

Failing to recognize the reality of the situation runs the risk of crowding out other more promising treatments and creating animosity where none should exist.

What has been occurring is a continual shifting of goalposts with each negative hydroxychloroquine study. Those in favor of the drug protest that a trial did not include azithromycin or zinc or wasn't given at the right time to the right patients. While there may be biological plausibility to treating illness early or combining treatments with zinc, it can only be definitively shown in a randomized, controlled prospective study.

The bottom line: A study that only looks at past outcomes in one group of patients – even when well conducted – is at most hypothesis generating and cannot be used as the sole basis for a new treatment paradigm.

Some may argue that there is no time to wait for definitive studies, but no treatment is benign. The risk/benefit ratio is not the same for every possible use of the drug. For example, hydroxychloroquine has a long record of use in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus (whose patients are facing shortages because of COVID-19 related demand). But the risk of side effects for many of these patients is worth taking because of the substantial benefit the drug provides in treating those conditions.

In COVID-19, however, the disease apparently causes cardiac abnormalities in a great deal of many mild cases, a situation that should prompt caution when using any drugs that have known effects on the cardiac system -- drugs like hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin.

My Own Experience

It is not the case that every physician was biased against this drug from the start. Indeed, most of us wanted it to be shown to be beneficial, as it was a generic drug that was widely available and very familiar. In fact, early in the pandemic I prescribed it to hospitalized patients on two occasions per a hospital protocol. However, it is impossible for me as a sole clinician to know whether it worked, was neutral, or was harmful. In recent days, however, I have found the hydroxychloroquine talk to have polluted the atmosphere. One recent patient was initially refusing remdesivir, a drug proven in large randomized trials to have effectiveness, because he had confused it with hydroxychloroquine.

Moving On to Other COVID Treatments: What a Treatment Should Do

The story of hydroxychloroquine illustrates a fruitless search for what we are actually looking for in a COVID-19 treatment. In short, we are looking for a medication that can decrease symptoms, decrease complications, hasten recovery, decrease hospitalizations, decrease contagiousness, decrease deaths, and prevent infection. While it is unlikely to find a single antiviral that can accomplish all of these, fulfilling even just one is important.

For example, remdesivir hastens recovery and dexamethasone decreases mortality. Definitive results of the use of convalescent plasma and immunomodulating drugs such as siltuxamab, baricitinib, and anakinra (for use in the cytokine storms characteristic of severe disease) are still pending, as are the trials with monoclonal antibodies.

While it was crucial that the medical and scientific community definitively answer the questions surrounding the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19, it is time to face the facts and accept that its use for the treatment of this disease is not likely to be beneficial. Failing to recognize the reality of the situation runs the risk of crowding out other more promising treatments and creating animosity where none should exist.

Dr. Adalja is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. He has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and the system of care for infectious disease emergencies, and as an external advisor to the New York City Health and Hospital Emergency Management Highly Infectious Disease training program, as well as on a FEMA working group on nuclear disaster recovery. Dr. Adalja is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security. He was a coeditor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine, the Emergency Medicine CorePendium, Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple, UpToDate's section on biological terrorism, and a NATO volume on bioterrorism. He has also published in such journals as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Annals of Emergency Medicine. He is a board-certified physician in internal medicine, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. Follow him on Twitter: @AmeshAA

Catching colds may help protect kids from Covid

A new study shows that the immune system's response to colds can help prepare it to defend against COVID-19 - but only in the very young.

A common cold virus causes the immune system to produce T cells that also provide protection against SARS-CoV-2, according to new research. The study, published last month in PNAS, shows that this effect is most pronounced in young children. The finding may help explain why most young people who have been exposed to the cold-causing coronavirus have not developed serious cases of COVID-19.

One curiosity stood out in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic – why were so few kids getting sick. Generally young children and the elderly are the most vulnerable to disease outbreaks, particularly viral infections, either because their immune systems are not fully developed or they are starting to fail.

But solid information on the new infection was so scarce that many public health officials acted on the precautionary principle, assumed a worst-case scenario, and applied the broadest, most restrictive policies to all people to try to contain the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

One early thought was that lockdowns worked and kids (ages 6 months to 17 years) simply were not being exposed to the virus. So it was a shock when data started to come in showing that well over half of them carried antibodies to the virus, indicating exposure without getting sick. That trend grew over time and the latest tracking data from the CDC shows that 96.3 percent of kids in the U.S. now carry those antibodies.

Antibodies are relatively quick and easy to measure, but some scientists are exploring whether the reactions of T cells could serve as a more useful measure of immune protection.

But that couldn't be the whole story because antibody protection fades, sometimes as early as a month after exposure and usually within a year. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 has been spewing out waves of different variants that were more resistant to antibodies generated by their predecessors. The resistance was so significant that over time the FDA withdrew its emergency use authorization for a handful of monoclonal antibodies with earlier approval to treat the infection because they no longer worked.

Antibodies got most of the attention early on because they are part of the first line response of the immune system. Antibodies can bind to viruses and neutralize them, preventing infection. They are relatively quick and easy to measure and even manufacture, but as SARS-CoV-2 showed us, often viruses can quickly evolve to become more resistant to them. Some scientists are exploring whether the reactions of T cells could serve as a more useful measure of immune protection.

Kids, colds and T cells

T cells are part of the immune system that deals with cells once they have become infected. But working with T cells is much more difficult, takes longer, and is more expensive than working with antibodies. So studies often lags behind on this part of the immune system.

A group of researchers led by Annika Karlsson at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden focuses on T cells targeting virus-infected cells and, unsurprisingly, saw that they can play a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Other labs have shown that vaccination and natural exposure to the virus generates different patterns of T cell responses.

The Swedes also looked at another member of the coronavirus family, OC43, which circulates widely and is one of several causes of the common cold. The molecular structure of OC43 is similar to its more deadly cousin SARS-CoV-2. Sometimes a T cell response to one virus can produce a cross-reactive response to a similar protein structure in another virus, meaning that T cells will identify and respond to the two viruses in much the same way. Karlsson looked to see if T cells for OC43 from a wide age range of patients were cross-reactive to SARS-CoV-2.

And that is what they found, as reported in the PNAS study last month; there was cross-reactive activity, but it depended on a person’s age. A subset of a certain type of T cells, called mCD4+,, that recognized various protein parts of the cold-causing virus, OC43, expressed on the surface of an infected cell – also recognized those same protein parts from SARS-CoV-2. The T cell response was lower than that generated by natural exposure to SARS-CoV-2, but it was functional and thus could help limit the severity of COVID-19.

“One of the most politicized aspects of our pandemic response was not accepting that children are so much less at risk for severe disease with COVID-19,” because usually young children are among the most vulnerable to pathogens, says Monica Gandhi, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“The cross-reactivity peaked at age six when more than half the people tested have a cross-reactive immune response,” says Karlsson, though their sample is too small to say if this finding applies more broadly across the population. The vast majority of children as young as two years had OC43-specific mCD4+ T cell responses. In adulthood, the functionality of both the OC43-specific and the cross-reactive T cells wane significantly, especially with advanced age.

“Considering that the mortality rate in children is the lowest from ages five to nine, and higher in younger children, our results imply that cross-reactive mCD4+ T cells may have a role in the control of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children,” the authors wrote in their paper.

“One of the most politicized aspects of our pandemic response was not accepting that children are so much less at risk for severe disease with COVID-19,” because usually young children are among the most vulnerable to pathogens, says Monica Gandhi, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco and author of the book, Endemic: A Post-Pandemic Playbook, to be released by the Mayo Clinic Press this summer. The immune response of kids to SARS-CoV-2 stood our expectations on their head. “We just haven't seen this before, so knowing the mechanism of protection is really important.”

Why the T cell immune response can fade with age is largely unknown. With some viruses such as measles, a single vaccination or infection generates life-long protection. But respiratory tract infections, like SARS-CoV-2, cause a localized infection - specific to certain organs - and that response tends to be shorter lived than systemic infections that affect the entire body. Karlsson suspects the elderly might be exposed to these localized types of viruses less often. Also, frequent continued exposure to a virus that results in reactivation of the memory T cell pool might eventually result in “a kind of immunosenescence or immune exhaustion that is associated with aging,” Karlsson says. https://leaps.org/scientists-just-started-testing-a-new-class-of-drugs-to-slow-and-even-reverse-aging/particle-3 This fading protection is why older people need to be repeatedly vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2.

Policy implications

Following the numbers on COVID-19 infections and severity over the last three years have shown us that healthy young people without risk factors are not likely to develop serious disease. This latest study points to a mechanism that helps explain why. But the inertia of existing policies remains. How should we adjust policy recommendations based on what we know today?

The World Health Organization (WHO) updated their COVID-19 vaccination guidance on March 28. It calls for a focus on vaccinating and boosting those at risk for developing serious disease. The guidance basically shrugged its shoulders when it came to healthy children and young adults receiving vaccinations and boosters against COVID-19. It said the priority should be to administer the “traditional essential vaccines for children,” such as those that protect against measles, rubella, and mumps.

“As an immunologist and a mother, I think that catching a cold or two when you are a kid and otherwise healthy is not that bad for you. Children have a much lower risk of becoming severely ill with SARS-CoV-2,” says Karlsson. She has followed public health guidance in Sweden, which means that her young children have not been vaccinated, but being older, she has received the vaccine and boosters. Gandhi and her children have been vaccinated, but they do not plan on additional boosters.

The WHO got it right in “concentrating on what matters,” which is getting traditional childhood immunizations back on track after their dramatic decline over the last three years, says Gandhi. Nor is there a need for masking in schools, according to a study from the Catalonia region of Spain. It found “no difference in masking and spread in schools,” particularly since tracking data indicate that nearly all young people have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

Both researchers lament that public discussion has overemphasized the quickly fading antibody part of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 compared with the more durable T cell component. They say developing an efficient measure of T cell response for doctors to use in the clinic would help to monitor immunity in people at risk for severe cases of COVID-19 compared with the current method of toting up potential risk factors.

In this week's Friday Five: The eyes are the windows to the soul - and biological aging?

Plus, what bean genes mean for health and the planet, a breathing practice that could lower levels of tau proteins in the brain, AI beats humans at assessing heart health, and the benefits of "nature prescriptions"

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on new scientific theories and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the stories covered this week:

- The eyes are the windows to the soul - and biological aging?

- What bean genes mean for health and the planet

- This breathing practice could lower levels of tau proteins

- AI beats humans at assessing heart health

- Should you get a nature prescription?