The Promise of Pills That Know When You Swallow Them

A woman prepares to swallow a digital pill that can track whether she has taken her medication.

Dr. Sara Browne, an associate professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Diego, is a specialist in infectious diseases and, less formally, "a global health person." She often travels to southern Africa to meet with colleagues working on the twin epidemics of HIV and tuberculosis.

"This technology, in my opinion, is an absolute slam dunk for tuberculosis."

Lately she has asked them to name the most pressing things she can help with as a researcher based in a wealthier country. "Over and over and over again," she says, "the only thing they wanted to know is whether their patients are taking the drugs."

Tuberculosis is one of world's deadliest diseases; every year there are 10 million new infections and more than a million deaths. When a patient with tuberculosis is prescribed medicine to combat the disease, adherence to the regimen is important not just for the individual's health, but also for the health of the community. Poor adherence can lead to lengthier and more costly treatment and, perhaps more importantly, to drug-resistant strains of the disease -- an increasing global threat.

Browne is testing a new method to help healthcare workers track their patients' adherence with greater precision—close to exact precision even. They're called digital pills, and they involve a patient swallowing medicine as they normally would, only the capsule contains a sensor that—when it contacts stomach acid—transmits a signal to a small device worn on or near the body. That device in turn sends a signal to the patient's phone or tablet and into a cloud-based database. The fact that the pill has been swallowed has therefore been recorded almost in real time, and notice is available to whoever has access to the database.

"This technology, in my opinion, is an absolute slam dunk for tuberculosis," Browne says. TB is much more prevalent in poorer regions of the world—in Sub-Saharan Africa, for example—than in richer places like the U.S., where Browne's studies thus far have taken place. But when someone is diagnosed in the U.S., because of the risk to others if it spreads, they will likely have to deal with "directly observed therapy" to ensure that they take their medicines correctly.

DOT, as it's called, requires the patient to meet with a healthcare worker several days a week, or every day, so that the medicine intake can be observed in person -- an expensive and time-consuming process. Still, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website says (emphasis theirs), "DOT should be used for ALL patients with TB disease, including children and adolescents. There is no way to accurately predict whether a patient will adhere to treatment without this assistance."

Digital pills can help with both the cost and time involved, and potentially improve adherence in places where DOT is impossibly expensive. With the sensors, you can monitor a patient's adherence without a healthcare worker physically being in the room. Patients can live their normal lives and if they miss a pill, they can receive a reminder by text or a phone call from the clinic or hospital. "They can get on with their lives," said Browne. "They don't need the healthcare system to interrupt them."

A 56-year-old patient who participated in one of Browne's studies when he was undergoing TB treatment says that before he started taking the digital pills, he would go to the clinic at least once every day, except weekends. Once he switched to digital pills, he could go to work and spend time with his wife and children instead of fighting traffic every day to get to the clinic. He just had to wear a small patch on his abdomen, which would send the signal to a tablet provided by Browne's team. When he returned from work, he could see the results—that he'd taken the pill—in a database accessed via the tablet. (He could also see his heart rate and respiratory rate.) "I could do my daily activities without interference," he said.

Dr. Peter Chai, a medical toxicologist and emergency medicine physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, is studying digital pills in a slightly different context, to help fight the country's opioid overdose crisis. Doctors like Chai prescribe pain medicine, he says, but then immediately put the onus on the patient to decide when to take it. This lack of guidance can lead to abuse and addiction. Patients are often told to take the meds "as needed." Chai and his colleagues wondered, "What does that mean to patients? And are people taking more than they actually need? Because pain is such a subjective experience."

The patients "liked the fact that somebody was watching them."

They wanted to see what "take as needed" actually led to, so they designed a study with patients who had broken a bone and come to the hospital's emergency department to get it fixed. Those who were prescribed oxycodone—a pharmaceutical opioid for pain relief—got enough digital pills to last one week. They were supposed to take the pills as needed, or as many as three pills per day. When the pills were ingested, the sensor sent a signal to a card worn on a lanyard around the neck.

Chai and his colleagues were able to see exactly when the patients took the pills and how many, and to detect patterns of ingestion more precisely than ever before. They talked to the patients after the seven days were up, and Chai said most were happy to be taking digital pills. The patients saw it as a layer of protection from afar. "They liked the fact that somebody was watching them," Chai said.

Both doctors, Browne and Chai, are in early stages of studies with patients taking pre-exposure prophylaxis, medicines that can protect people with a high-risk of contracting HIV, such as injectable drug users. Without good adherence, patients leave themselves open to getting the virus. If a patient is supposed to take a pill at 2 p.m. but the digital pill sensor isn't triggered, the healthcare provider can have an automatic message sent as a reminder. Or a reminder to one of the patient's friends or loved ones.

"Like Swallowing Your Phone"?

Deven Desai, an associate professor of law and ethics at Georgia Tech, says that digital pills sound like a great idea for helping with patient adherence, a big issue that self-reporting doesn't fully solve. He likes the idea of a physician you trust having better information about whether you're taking your medication on time. "On the surface that's just cool," he says. "That's a good thing." But Desai, who formerly worked as academic research counsel at Google, said that some of the same questions that have come up in recent years with social media and the Internet in general also apply to digital pills.

"Think of it like your phone, but you swallowed it," he says. "At first it could be great, simple, very much about the user—in this case, the patient—and the data is going between you and your doctor and the medical people it ought to be going to. Wonderful. But over time, phones change. They become 'smarter.'" And when phones and other technologies become smarter, he says, the companies behind them tend to expand the type of data they collect, because they can. Desai says it will be crucial that prescribers be completely transparent about who is getting the patients' data and for what purpose.

"We're putting stuff in our body in good faith with our medical providers, and what if it turned out later that all of a sudden someone was data mining or putting in location trackers and we never knew about that?" Desai asks. "What science has to realize is if they don't start thinking about this, what could be a wonderful technology will get killed."

Leigh Turner, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota's Center for Bioethics, agrees with Desai that digital pills have great promise, and also that there are clear reasons to be concerned about their use. Turner compared the pills to credit cards and social media, in that the data from them can potentially be stolen or leaked. One question he would want answered before the pills were normalized: "What kind of protective measures are in place to make sure that personal information isn't spilling out and being acquired by others or used by others in unexpected and unwanted ways?"

If digital pills catch on, some experts worry that they may one day not be a voluntary technology.

Turner also wonders who will have access to the pills themselves. Only those who can afford both the medicine plus the smartphones that are currently required for their use? Or will people from all economic classes have access? If digital pills catch on, he also worries they may one day not be a voluntary technology.

"When it comes to digital pills, it's not something that's really being foisted on individuals. It's more something that people can be informed of and can choose to take or not to take," he says. "But down the road, I can imagine a scenario where we move away from purely voluntary agreements to it becoming more of an expectation."

He says it's easy to picture a scenario in which insurance companies demand that patient medicinal intake data be tracked and collected or else. Refuse to have your adherence tracked and you risk higher rates or even overall coverage. Maybe patients who don't take the digital pills suffer dire consequences financially or medically. "Maybe it becomes beneficial as much to health insurers and payers as it is to individual patients," Turner says.

In November 2017, the FDA approved the first-ever digital pill that includes a sensor, a drug called Abilify MyCite, made by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company. The drug, which is yet to be released, is used to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. With a built-in sensor developed by Proteus Digital Health, patients can give their doctors permission to see when exactly they are taking, or not taking, their meds. For patients with mental illness, the ability to help them stick to their prescribed regime can be life-saving.

But Turner wonders if Abilify is the best drug to be a forerunner for digital pills. Some people with schizophrenia might be suffering from paranoia, and perhaps giving them a pill developed by a large corporation that sends data from their body to be tracked by other people might not be the best idea. It could in fact exacerbate their sense of paranoia.

The Bottom Line: Protect the Data

We all have relatives who have pillboxes with separate compartments for each day of the week, or who carry pillboxes that beep when it's time to take the meds. But that's not always good enough for people with dementia, mental illness, drug addiction, or other life situations that make it difficult to remember to take their pills. Digital pills can play an important role in helping these people.

"The absolute principle here is that the data has to belong to the patient."

The one time the patient from Browne's study forgot to take his pills, he got a beeping reminder from his tablet that he'd missed a dose. "Taking a medication on a daily basis, sometimes we just forget, right?" he admits. "With our very accelerated lives nowadays, it helps us to remember that we have to take the medications. So patients are able to be on top of their own treatment."

Browne is convinced that digital pills can help people in developing countries with high rates of TB and HIV, though like Turner and Desai she cautions that patients' data must be protected. "I think it can be a tremendous technology for patient empowerment and I also think if properly used it can help the medical system to support patients that need it," she said. "But the absolute principle here is that the data has to belong to the patient."

New tech for prison reform spreads to 11 states

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, costing $182 billion per year, partly because its antiquated data systems often fail to identify people who should be released. A tech nonprofit is trying to change that.

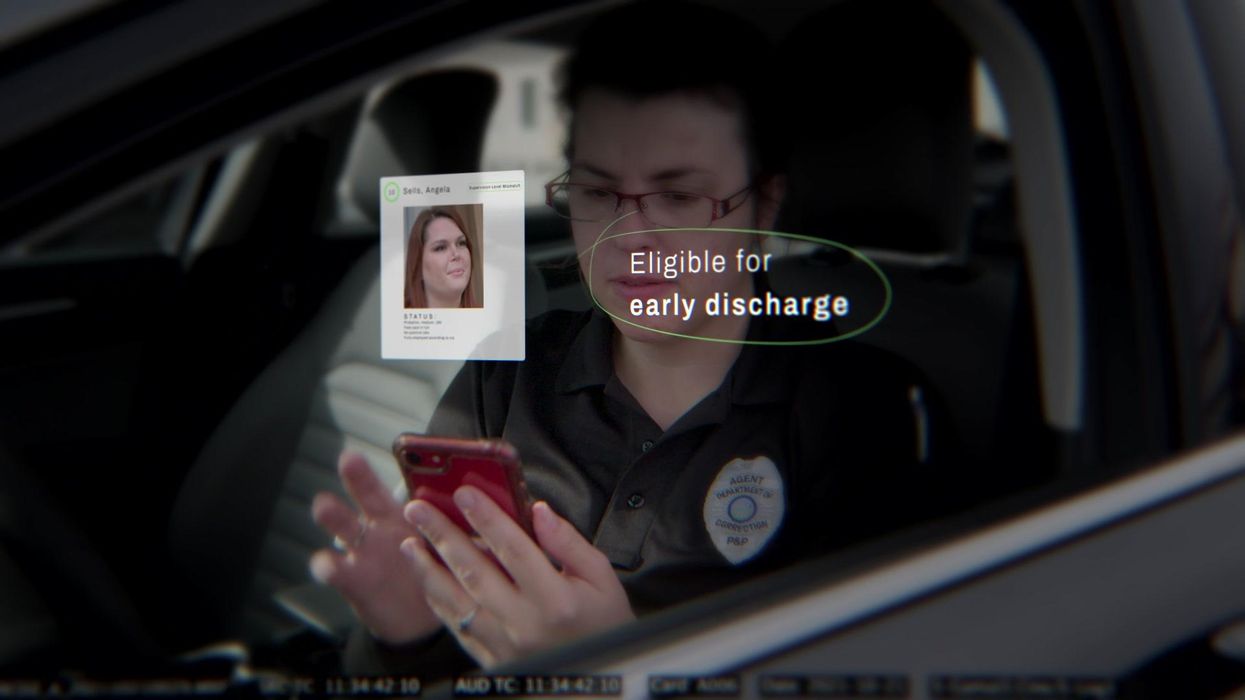

A new non-profit called Recidiviz is using data technology to reduce the size of the U.S. criminal justice system. The bi-coastal company (SF and NYC) is currently working with 11 states to improve their systems and, so far, has helped remove nearly 69,000 people — ones left floundering in jail or on parole when they should have been released.

“The root cause is fragmentation,” says Clementine Jacoby, 31, a software engineer who worked at Google before co-founding Recidiviz in 2019. In the 1970s and 80s, the U.S. built a series of disconnected data systems, and this patchwork is still being used by criminal justice authorities today. It requires parole officers to manually calculate release dates, leading to errors in many cases. “[They] have done everything they need to do to earn their release, but they're still stuck in the system,” Jacoby says.

Recidiviz has built a platform that connects the different databases, with the goal of identifying people who are already qualified for release but remain behind bars or on supervision. “Think of Recidiviz like Google Maps,” says Jacoby, who worked on Maps when she was at the tech giant. Google Maps takes in data from different sources – satellite images, street maps, local business data — and organizes it into one easy view. “Recidiviz does something similar with criminal justice data,” Jacoby explains, “making it easy to identify people eligible to come home or to move to less intensive levels of supervision.”

People like Jacoby’s uncle. His experience with incarceration is what inspired her passion for criminal justice reform in the first place.

The problems are vast

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world — 2 million people according to the watchdog group, Prison Policy Initiative — at a cost of $182 billion a year. The numbers could be a lot lower if not for an array of problems including inaccurate sentencing calculations, flawed algorithms and parole violations laws.

Sentencing miscalculations

To determine eligibility for release, the current system requires corrections officers to check 21 different requirements spread across five different databases for each of the 90 to 100 people under their supervision. These manual calculations are time prohibitive, says Jacoby, and fall victim to human error.

In addition, Recidiviz found that policies aimed at helping to reduce the prison population don’t always work correctly. A key example is time off for good behavior laws that allow inmates to earn one day off for every 30 days of good behavior. Some states' data systems are built to calculate time off as one day per month of good behavior, rather than per day. Over the course of a decade-long sentence, Jacoby says these miscalculations can lead to a huge discrepancy in the calculated release data and the actual release date.

Algorithms

Commercial algorithm-based software systems for risk assessment continue to be widely used in the criminal justice system, even though a 2018 study published in Science Advances exposed their limitations. After the study went viral, it took three years for the Justice Department to issue a report on their own flawed algorithms used to reduce the federal prison population as part of the 2018 First Step Act. The program, it was determined, overestimated the risk of putting inmates of color into early-release programs.

Despite its name, Recidiviz does not build these types of algorithms for predicting recidivism, or whether someone will commit another crime after being released from prison. Rather, Jacoby says the company’s "descriptive analytics” approach is specifically intended to weed out incarceration inequalities and avoid algorithmic pitfalls.

Parole violation laws

Research shows that 350,000 people a year — about a quarter of the total prison population — are sent back not because they’ve committed another crime, but because they’ve broken a specific rule of their probation. “Things that wouldn't send you or I to prison, but would send someone on parole,” such as crossing county lines or being in the presence of alcohol when they shouldn’t be, are inflating the prison population, says Jacoby.

It’s personal for the co-founder and CEO

“I grew up with an uncle who went into the prison system,” Jacoby says. At 19, he was sentenced to ten years in prison for a non-violent crime. A few months after being released from jail, he was sent back for a non-violent parole violation.

“For my family, the fact that one in four prison admissions are driven not by a crime but by someone who's broken a rule on probation and parole was really profound because that happened to my uncle,” Jacoby says. The experience led her to begin studying criminal justice in high school, then college. She continued her dive into how the criminal justice system works as part of her Passion Project while at Google, a program that allows employees to spend 20 percent of their time on pro-bono work. Two colleagues whose family members had also been stuck in the system joined her.

As part of the project, Jacoby interviewed hundreds of people involved in the criminal justice system. “Those on the right, those on the left, agreed that bad data was slowing down reform,” she says. Their research brought them to North Dakota where they began to understand the root of the problem. The corrections department is making “huge, consequential decisions every day [without] … the data,” Jacoby says. In a new video by Recidiviz not yet released, Jacoby recounts her exchange with the state’s director of corrections who told her, “‘It’s not that we have the data and we just don’t know how to make it public; we don’t have the information you think we have.'"

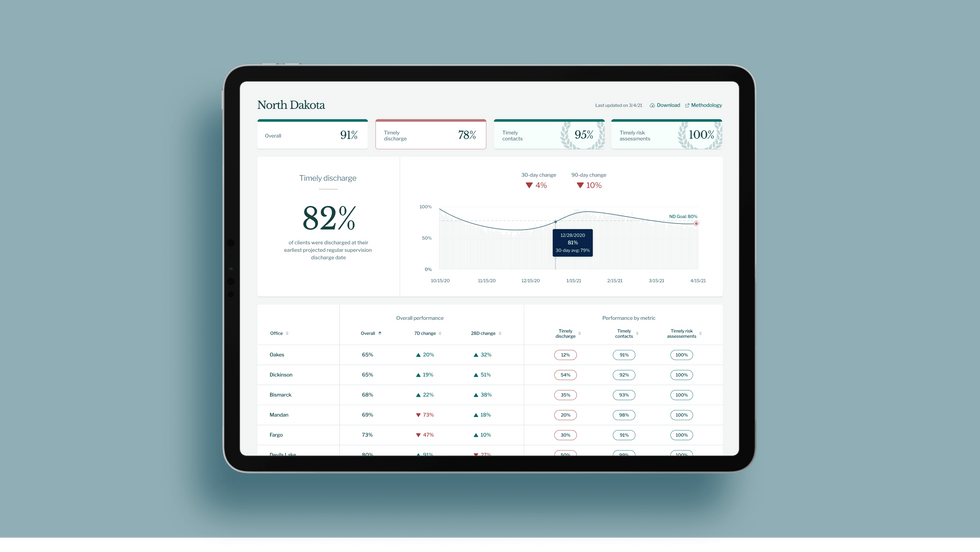

A mock-up (with fake data) of the types of dashboards and insights that Recidiviz provides to state governments.

Recidiviz

As a software engineer, Jacoby says the comment made no sense to her — until she witnessed it first-hand. “We spent a lot of time driving around in cars with corrections directors and parole officers watching them use these incredibly taxing, frankly terrible, old data systems,” Jacoby says.

As they weeded through thousands of files — some computerized, some on paper — they unearthed the consequences of bad data: Hundreds of people in prison well past their release date and thousands more whose release from parole was delayed because of minor paperwork issues. They found individuals stuck in parole because they hadn’t checked one last item off their eligibility list — like simply failing to provide their parole officer with a paystub. And, even when parolees advocated for themselves, the archaic system made it difficult for their parole officers to confirm their eligibility, so they remained in the system. Jacoby and her team also unpacked specific policies that drive racial disparities — such as fines and fees.

The Solution

It’s more than a trivial technical challenge to bring the incomplete, fragmented data onto a 21st century data platform. It takes months for Recidiviz to sift through a state’s information systems to connect databases “with the goal of tracking a person all the way through their journey and find out what’s working for 18- to 25-year-old men, what’s working for new mothers,” explains Jacoby in the video.

TED Talk: How bad data traps people in the U.S. justice system

TED Fellow Clementine Jacoby's TED Talk went live on Jan. 13. It describes how we can fix bad data in the criminal justice system, "bringing thousands of people home, reducing costs and improving public safety along the way."

Clementine Jacoby • TED2022

Ojmarrh Mitchell, an associate professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University, who is not involved with the company, says what Recidiviz is doing is “remarkable.” His perspective goes beyond academic analysis. In his pre-academic years, Mitchell was a probation officer, working within the framework of the “well known, but invisible” information sharing issues that plague criminal justice departments. The flexibility of Recidiviz’s approach is what makes it especially innovative, he says. “They identify the specific gaps in each jurisdiction and tailor a solution for that jurisdiction.”

On the downside, the process used by Recidiviz is “a bit opaque,” Mitchell says, with few details available on how Recidiviz designs its tools and tracks outcomes. By sharing more information about how its actions lead to progress in a given jurisdiction, Recidiviz could help reformers in other places figure out which programs have the best potential to work well.

The eleven states in which Recidiviz is working include California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Pennsylvania and Tennessee. And a pilot program launched last year in Idaho, if scaled nationally, with could reduce the number of people in the criminal justice system by a quarter of a million people, Jacoby says. As part of the pilot, rather than relying on manual calculations, Recidiviz is equipping leaders and the probation officers with actionable information with a few clicks of an app that Recidiviz built.

Mitchell is disappointed that there’s even the need for Recidiviz. “This is a problem that government agencies have a responsibility to address,” he says. “But they haven’t.” For one company to come along and fill such a large gap is “remarkable.”

How Leqembi became the biggest news in Alzheimer’s disease in 40 years, and what comes next

Betsy Groves, 73, with her granddaughter. Groves learned in 2021 that she has Alzheimer's disease. She hopes to take Leqembi, a drug approved by the FDA last week.

A few months ago, Betsy Groves traveled less than a mile from her home in Cambridge, Mass. to give a talk to a bunch of scientists. The scientists, who worked for the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai, wanted to know how she lived her life, how she thought about her future, and what it was like when a doctor’s appointment in 2021 gave her the worst possible news. Groves, 73, has Alzheimer’s disease. She caught it early, through a lumbar puncture that showed evidence of amyloid, an Alzheimer’s hallmark, in her cerebrospinal fluid. As a way of dealing with her diagnosis, she joined the Alzheimer’s Association’s National Early-Stage Advisory Board, which helped her shift into seeing her diagnosis as something she could use to help others.

After her talk, Groves stayed for lunch with the scientists, who were eager to put a face to their work. Biogen and Eisai were about to release the first drug to successfully combat Alzheimer’s in 40 years of experimental disaster. Their drug, which is known by the scientific name lecanemab and the marketing name Leqembi, was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last Friday, Jan. 6, after a study in 1,800 people showed that it reduced cognitive decline by 27 percent over 18 months.

It is no exaggeration to say that this result is a huge deal. The field of Alzheimer’s drug development has been absolutely littered with failures. Almost everything researchers have tried has tanked in clinical trials. “Most of the things that we've done have proven not to be effective, and it's not because we haven’t been taking a ton of shots at goal,” says Anton Porsteinsson, director of the University of Rochester Alzheimer's Disease Care, Research, and Education Program, who worked on the lecanemab trial. “I think it's fair to say you don't survive in this field unless you're an eternal optimist.”

As far back as 1984, a cure looked like it was within reach: Scientists discovered that the sticky plaques that develop in the brains of those who have Alzheimer’s are made up of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. Buildup of beta-amyloid seemed to be sufficient to disrupt communication between, and eventually kill, memory cells. If that was true, then the cure should be straightforward: Stop the buildup of beta-amyloid; stop the Alzheimer’s disease.

It wasn’t so simple. Over the next 38 years, hundreds of drugs designed either to interfere with the production of abnormal amyloid or to clear it from the brain flamed out in trials. It got so bad that neuroscience drug divisions at major pharmaceutical companies (AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, GSK, Amgen) closed one by one, leaving the field to smaller, scrappier companies, like Cambridge-based Biogen and Tokyo-based Eisai. Some scientists began to dismiss the amyloid hypothesis altogether: If this protein fragment was so important to the disease, why didn’t ridding the brain of it do anything for patients? There was another abnormal protein that showed up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, called tau. Some researchers defected to the tau camp, or came to believe the proteins caused damage in combination.

The situation came to a head in 2021, when the FDA granted provisional approval to a drug called aducanumab, marketed as Aduhelm, against the advice of its own advisory council. The approval was based on proof that Aduhelm reduced beta-amyloid in the brain, even though one research trial showed it had no effect on people’s symptoms or daily life. Aduhelm could also cause serious side effects, like brain swelling and amyloid related imaging abnormalities (known as ARIA, these are basically micro-bleeds that appear on MRI scans). Without a clear benefit to memory loss that would make these risks worth it, Medicare refused to pay for Aduhelm among the general population. Two congressional committees launched an investigation into the drug’s approval, citing corporate greed, lapses in protocol, and an unjustifiably high price. (Aduhelm was also produced by the pharmaceutical company Biogen.)

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world.

So far, Leqembi is like Aduhelm in that it has been given accelerated approval only for its ability to remove amyloid from the brain. Both are monoclonal antibodies that direct the immune system to attack and clear dysfunctional beta-amyloid. The difference is that, while that’s all Aduhelm was ever shown to do, Leqembi’s makers have already asked the FDA to give it full approval – a decision that would increase the likelihood that Medicare will cover it – based on data that show it also improves Alzheimer’s sufferer’s lives. Leqembi targets a different type of amyloid, a soluble version called “protofibrils,” and that appears to change the effect. “It can give individuals and their families three, six months longer to be participating in daily life and living independently,” says Claire Sexton, PhD, senior director of scientific programs & outreach for the Alzheimer's Association. “These types of changes matter for individuals and for their families.”

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. It does not halt or reverse the disease, and people do not get better. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world. It has “a rather small effect,” wrote NIH Alzheimer’s researcher Madhav Thambisetty, MD, PhD, in an email to Leaps.org. “It is unclear how meaningful this difference will be to patients, and it is unlikely that this level of difference will be obvious to a patient (or their caregivers).” Another issue is cost: Leqembi will become available to patients later this month, but Eisai is setting the price at $26,500 per year, meaning that very few patients will be able to afford it unless Medicare chooses to reimburse them for it.

The same side effects that plagued Aduhelm are common in Leqembi treatment as well. In many patients, amyloid doesn’t just accumulate around neurons, it also forms deposits in the walls of blood vessels. Blood vessels that are shot through with amyloid are more brittle. If you infuse a drug that targets amyloid, brittle blood vessels in the brain can develop leakage that results in swelling or bleeds. Most of these come with no symptoms, and are only seen during testing, which is why they are called “imaging abnormalities.” But in situations where patients have multiple diseases or are prescribed incompatible drugs, they can be serious enough to cause death. The three deaths reported from Leqembi treatment (so far) are enough to make Thambisetty wonder “how well the drug may be tolerated in real world clinical practice where patients are likely to be sicker and have multiple other medical conditions in contrast to carefully selected patients in clinical trials.”

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval.

Still, there are reasons to be excited. A successful Alzheimer’s drug can pave the way for combination studies, in which patients try a known effective drug alongside newer, more experimental ones; or preventative studies, which take place years before symptoms occur. It also represents enormous strides in researchers’ understanding of the disease. For example, drug dosages have increased massively—in some cases quadrupling—from the early days of Alzheimer’s research. And patient selection for studies has changed drastically as well. Doctors now know that you’ve got to catch the disease early, through PET-scans or CSF tests for amyloid, if you want any chance of changing its course.

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval. His lab already uses blood tests for different types of amyloid, for different types of tau, and for measures of neuroinflammation, neural damage, and synaptic health, but commercially available versions from companies like C2N, Quest, and Fuji Rebio are likely to hit the market in the next couple of years. “[They are] going to transform the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease,” Porsteinsson says. “If someone is experiencing memory problems, their physicians will be able to order a blood test that will tell us if this is the result of changes in your brain due to Alzheimer's disease. It will ultimately make it much easier to identify people at a very early stage of the disease, where they are most likely to benefit from treatment.”

Learn more about new blood tests to detect Alzheimer's

Early detection can help patients for more philosophical reasons as well. Betsy Groves credits finding her Alzheimer’s early with giving her the space to understand and process the changes that were happening to her before they got so bad that she couldn’t. She has been able to update her legal documents and, through her role on the Advisory Group, help the Alzheimer’s Association with developing its programs and support services for people in the early stages of the disease. She still drives, and because she and her husband love to travel, they are hoping to get out of grey, rainy Cambridge and off to Texas or Arizona this spring.

Because her Alzheimer’s disease involves amyloid deposits (a “substantial portion” do not, says Claire Sexton, which is an additional complication for research), and has not yet reached an advanced stage, Groves may be a good candidate to try Leqembi. She says she’d welcome the opportunity to take it. If she can get access, Groves hopes the drug will give her more days to be fully functioning with her husband, daughters, and three grandchildren. Mostly, she avoids thinking about what the latter stages of Alzheimer’s might be like, but she knows the time will come when it will be her reality. “So whatever lecanemab can do to extend my more productive ways of engaging with relationships in the world,” she says. “I'll take that in a minute.”