This Mom Donated Her Lost Baby’s Tissue to Research

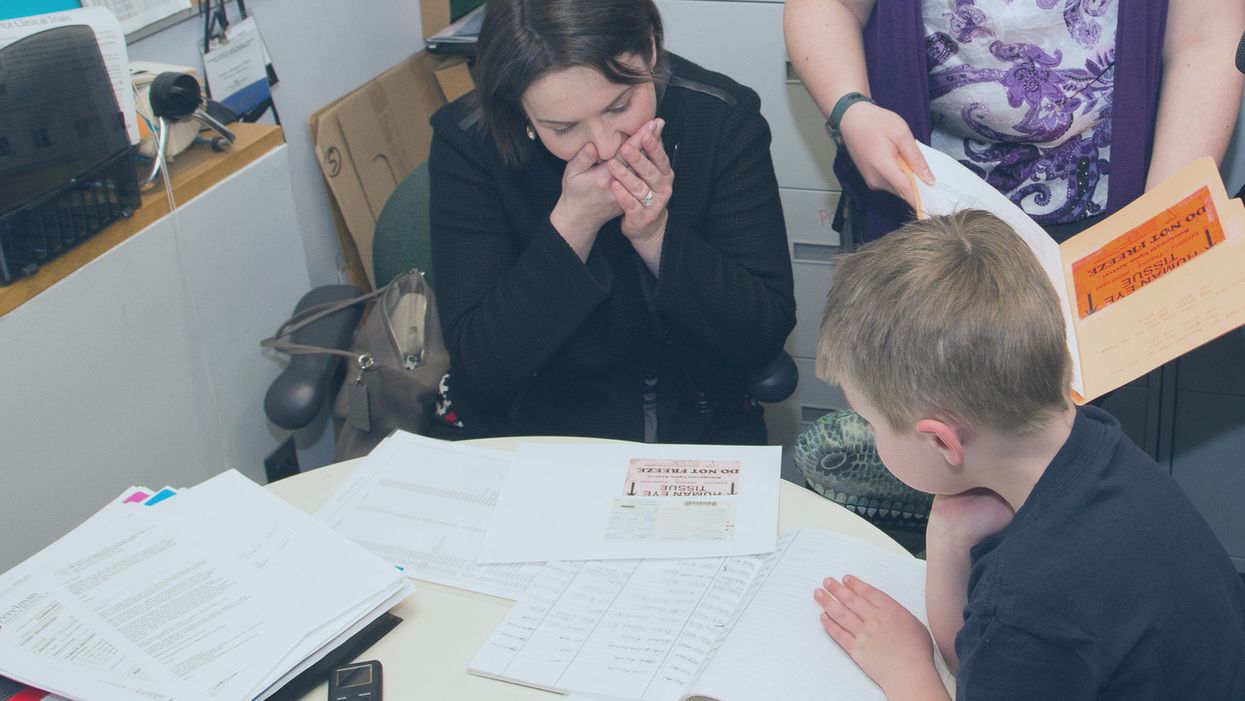

Sarah Gray views data about the use of her deceased son Thomas' retinal tissue in research for retinoblastoma, a cancer of the eye, at the University of Pennsylvania, while her son Callum looks on.

The twin boys growing within her womb filled Sarah Gray with both awe and dread. The sonogram showed that one, Callum, seemed to be the healthy child she and husband Ross had long sought; the other, Thomas, had anencephaly, a fatal developmental disorder of the skull and brain that likely would limit his life to hours. The options were to carry the boys to term or terminate both.

The decision to donate Thomas' tissue to research comforted Sarah. It brought a sense of purpose and meaning to her son's anticipated few breaths.

Sarah learned that researchers prize tissue as essential to better understanding and eventually treating the rare disorder that afflicted her son. And that other tissue from the developing infant might prove useful for transplant or basic research.

Animal models have been useful in figuring out some of the basics of genetics and how the body responds to disease. But a mouse is not a man. The new tools of precision medicine that measure gene expression, proteins and metabolites – the various chemical products and signals that fluctuate in health and illness – are most relevant when studying human tissue directly rather than in animals.

The decision to donate Thomas' tissue to research comforted Sarah. It brought a sense of purpose and meaning to her son's anticipated few breaths.

Thomas Gray

(Photo credit: Mark Walpole)

Later Sarah would track down where some of the donated tissues had been sent and how they were being used. It was a rare initiative that just may spark a new kind of relationship between donor families and researchers who use human tissue.

Organ donation for transplant gets all the attention. That process is simple, direct, life saving, the stories are easy to understand and play out regularly in the media. Reimbursement fully covers costs.

Tissue donation for research is murkier. Seldom is there a direct one-to-one correlation between individual donation and discovery; often hundreds, sometimes thousands of samples are needed to tease out the basic mechanisms of a disease, even more to develop a treatment or cure. The research process can be agonizingly slow. And somebody has to pay for collecting, processing, and getting donations into the hands of appropriate researchers. That story rarely is told, so most people are not even aware it is possible, let alone vital to research.

Gray set out on a quest to follow where Thomas' tissue had gone and how it was being used to advance research and care.

The dichotomy between transplant and research became real for Sarah several months after the birth of her twins, and Thomas' brief life, at a meeting for families of transplant donors. Many of the participants had found closure to their grieving through contact with grateful recipients of a heart, liver, or kidney who had gained a new lease on life. But there was no similar process for those who donated for research. Sarah felt a bit, well, jealous. She wanted that type of connection too.

Gray set out on a quest to follow where Thomas' tissue had gone and how it was being used to advance research and care. Those encounters were as novel for the researchers as they were for Sarah. The experience turned her into an advocate for public education and financial and operational changes to put tissue donation for research on par with donations for transplant.

Thomas' retina had been collected and processed by the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI), a nonprofit that performs such services for researchers on a cost recovery basis with support from the National Institutes of Health. The tissue was passed on to Arupa Ganguly, who is studying retinoblastoma, a cancer of the eye, at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ganguly was surprised and apprehensive months later when NDRI emailed her saying the mother of donated tissue wanted to learn more about how the retina was being used. That was unusual because research donations generally are anonymous.

The geneticist waited a day or two, then wrote an explanation of her work and forwarded it back through NDRI. Soon the researcher and mother were talking by phone and Sarah would visit the lab. Even then, Ganguly felt very uncomfortable. "Something very bad happened to your son Thomas but it was a benefit for me, so I'm feeling very bad," she told Sarah.

"And Sarah said, Arupa, you were the only ones who wanted his retinas. If you didn't request them, they would be buried in the ground. It gives me a sense of fulfillment to know that they were of some use," Ganguly recalls. And her apprehension melted away. The two became friends and have visited several times.

Sarah Gray visits Dr. Arupa Ganguly at the University of Pennsylvania's Genetic Diagnostic Laboratory.

(Photo credit: Daniel Burke)

Reading Sarah Gray's story led Gregory Grossman to reach out to the young mother and to create Hope and Healing, a program that brings donors and researchers together. Grossman is director of research programs at Eversight, a large network of eye banks that stretches from the Midwest to the East Coast. It supplies tissue for transplant and ocular research.

"Research seems a cold and distant thing," Grossman says, "we need to educate the general public on the importance and need for tissue donations for research, which can help us better understand disease and find treatments."

"Our own internal culture needs to be shifted too," he adds. "Researchers and surgeons can forget that these are precious gifts, they're not a commodity, they're not manufactured. Without people's generosity this doesn't exist."

The initial Hope and Healing meetings between researchers and donor families have gone well and Grossman hopes to increase them to three a year with support from the Lions Club. He sees it as a crucial element in trying to reverse the decline in ocular donations even while research needs continue to grow.

What people hear about is "Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks, they hear about the scandals, they don't hear about the good news. I would like to change that."

Since writing about her experience in the 2016 book "A Life Everlasting," Gray has come to believe that potential donor families, and even people who administer donation programs, often are unaware of the possibility of donating for research.

And roadblocks are common for those who seek to do so. Just like her, many families have had to be persistent in their quest to donate, and even educate their medical providers. But Sarah believes the internet is facilitating creation of a grassroots movement of empowered donors who are pushing procurement systems to be more responsive to their desires to donate for research. A lot of it comes through anecdote, stories, and people asking, if they have done it in Virginia, or Ohio, why can't we do it here?

Callum Gray and Dr. Arupa Ganguly hug during his family's visit to the lab.

(Photo credit: Daniel Burke)

Gray has spoken at medical and research facilities and at conferences. Some researchers are curious to have contact with the families of donors, but she believes the research system fosters the belief that "you don't want to open that can of worms." And lurking in the background may be a fear of liability issues somehow arising.

"I believe that 99 percent of what happens in research is very positive, and those stories would come out if the connections could be made," says Sarah Gray. But what they hear about is "Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks, they hear about the scandals, they don't hear about the good news. I would like to change that."

Autonomous, indoor farming gives a boost to crops

Artificial Intelligence is already helping to grow some of the food we eat.

The glass-encased cabinet looks like a display meant to hold reasonably priced watches, or drugstore beauty creams shipped from France. But instead of this stagnant merchandise, each of its five shelves is overgrown with leaves — moss-soft pea sprouts, spikes of Lolla rosa lettuces, pale bok choy, dark kale, purple basil or red-veined sorrel or green wisps of dill. The glass structure isn’t a cabinet, but rather a “micro farm.”

The gadget is on display at the Richmond, Virginia headquarters of Babylon Micro-Farms, a company that aims to make indoor farming in the U.S. more accessible and sustainable. Babylon’s soilless hydroponic growing system, which feeds plants via nutrient-enriched water, allows chefs on cruise ships, cafeterias and elsewhere to provide home-grown produce to patrons, just seconds after it’s harvested. Currently, there are over 200 functioning systems, either sold or leased to customers, and more of them are on the way.

The chef-farmers choose from among 45 types of herb and leafy-greens seeds, plop them into grow trays, and a few weeks later they pick and serve. While success is predicated on at least a small amount of these humans’ care, the systems are autonomously surveilled round-the-clock from Babylon’s base of operations. And artificial intelligence is helping to run the show.

Babylon piloted the use of specialized cameras that take pictures in different spectrums to gather some less-obvious visual data about plants’ wellbeing and alert people if something seems off.

Imagine consistently perfect greens and tomatoes and strawberries, grown hyper-locally, using less water, without chemicals or environmental contaminants. This is the hefty promise of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) — basically, indoor farms that can be hydroponic, aeroponic (plant roots are suspended and fed through misting), or aquaponic (where fish play a role in fertilizing vegetables). But whether they grow 4,160 leafy-green servings per year, like one Babylon farm, or millions of servings, like some of the large, centralized facilities starting to supply supermarkets across the U.S., they seek to minimize failure as much as possible.

Babylon’s soilless hydroponic growing system

Courtesy Babylon Micro-Farms

Here, AI is starting to play a pivotal role. CEA growers use it to help “make sense of what’s happening” to the plants in their care, says Scott Lowman, vice president of applied research at the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research (IALR) in Virginia, a state that’s investing heavily in CEA companies. And although these companies say they’re not aiming for a future with zero human employees, AI is certainly poised to take a lot of human farming intervention out of the equation — for better and worse.

Most of these companies are compiling their own data sets to identify anything that might block the success of their systems. Babylon had already integrated sensor data into its farms to measure heat and humidity, the nutrient content of water, and the amount of light plants receive. Last year, they got a National Science Foundation grant that allowed them to pilot the use of specialized cameras that take pictures in different spectrums to gather some less-obvious visual data about plants’ wellbeing and alert people if something seems off. “Will this plant be healthy tomorrow? Are there things…that the human eye can't see that the plant starts expressing?” says Amandeep Ratte, the company’s head of data science. “If our system can say, Hey, this plant is unhealthy, we can reach out to [users] preemptively about what they’re doing wrong, or is there a disease at the farm?” Ratte says. The earlier the better, to avoid crop failures.

Natural light accounts for 70 percent of Greenswell Growers’ energy use on a sunny day.

Courtesy Greenswell Growers

IALR’s Lowman says that other CEA companies are developing their AI systems to account for the different crops they grow — lettuces come in all shapes and sizes, after all, and each has different growing needs than, for example, tomatoes. The ways they run their operations differs also. Babylon is unusual in its decentralized structure. But centralized growing systems with one main location have variabilities, too. AeroFarms, which recently declared bankruptcy but will continue to run its 140,000-square foot vertical operation in Danville, Virginia, is entirely enclosed and reliant on the intense violet glow of grow lights to produce microgreens.

Different companies have different data needs. What data is essential to AeroFarms isn’t quite the same as for Greenswell Growers located in Goochland County, Virginia. Raising four kinds of lettuce in a 77,000-square-foot automated hydroponic greenhouse, the vagaries of naturally available light, which accounts for 70 percent of Greenswell’s energy use on a sunny day, affect operations. Their tech needs to account for “outside weather impacts,” says president Carl Gupton. “What adjustments do we have to make inside of the greenhouse to offset what's going on outside environmentally, to give that plant optimal conditions? When it's 85 percent humidity outside, the system needs to do X, Y and Z to get the conditions that we want inside.”

AI will help identify diseases, as well as when a plant is thirsty or overly hydrated, when it needs more or less calcium, phosphorous, nitrogen.

Nevertheless, every CEA system has the same core needs — consistent yield of high quality crops to keep up year-round supply to customers. Additionally, “Everybody’s got the same set of problems,” Gupton says. Pests may come into a facility with seeds. A disease called pythium, one of the most common in CEA, can damage plant roots. “Then you have root disease pressures that can also come internally — a change in [growing] substrate can change the way the plant performs,” Gupton says.

AI will help identify diseases, as well as when a plant is thirsty or overly hydrated, when it needs more or less calcium, phosphorous, nitrogen. So, while companies amass their own hyper-specific data sets, Lowman foresees a time within the next decade “when there will be some type of [open-source] database that has the most common types of plant stress identified” that growers will be able to tap into. Such databases will “create a community and move the science forward,” says Lowman.

In fact, IALR is working on assembling images for just such a database now. On so-called “smart tables” inside an Institute lab, a team is growing greens and subjects them to various stressors. Then, they’re administering treatments while taking images of every plant every 15 minutes, says Lowman. Some experiments generate 80,000 images; the challenge lies in analyzing and annotating the vast trove of them, marking each one to reflect outcome—for example increasing the phosphate delivery and the plant’s response to it. Eventually, they’ll be fed into AI systems to help them learn.

For all the enthusiasm surrounding this technology, it’s not without downsides. Training just one AI system can emit over 250,000 pounds of carbon dioxide, according to MIT Technology Review. AI could also be used “to enhance environmental benefit for CEA and optimize [its] energy consumption,” says Rozita Dara, a computer science professor at the University of Guelph in Canada, specializing in AI and data governance, “but we first need to collect data to measure [it].”

The chef-farmers can choose from 45 types of herb and leafy-greens seeds.

Courtesy Babylon Micro-Farms

Any system connected to the Internet of Things is also vulnerable to hacking; if CEA grows to the point where “there are many of these similar farms, and you're depending on feeding a population based on those, it would be quite scary,” Dara says. And there are privacy concerns, too, in systems where imaging is happening constantly. It’s partly for this reason, says Babylon’s Ratte, that the company’s in-farm cameras all “face down into the trays, so the only thing [visible] is pictures of plants.”

Tweaks to improve AI for CEA are happening all the time. Greenswell made its first harvest in 2022 and now has annual data points they can use to start making more intelligent choices about how to feed, water, and supply light to plants, says Gupton. Ratte says he’s confident Babylon’s system can already “get our customers reliable harvests. But in terms of how far we have to go, it's a different problem,” he says. For example, if AI could detect whether the farm is mostly empty—meaning the farm’s user hasn’t planted a new crop of greens—it can alert Babylon to check “what's going on with engagement with this user?” Ratte says. “Do they need more training? Did the main person responsible for the farm quit?”

Lowman says more automation is coming, offering greater ability for systems to identify problems and mitigate them on the spot. “We still have to develop datasets that are specific, so you can have a very clear control plan, [because] artificial intelligence is only as smart as what we tell it, and in plant science, there's so much variation,” he says. He believes AI’s next level will be “looking at those first early days of plant growth: when the seed germinates, how fast it germinates, what it looks like when it germinates.” Imaging all that and pairing it with AI, “can be a really powerful tool, for sure.”

Scientists make progress with growing organs for transplants

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have laid the foundations for growing synthetic embryos that could develop a beating heart, gut and brain.

Story by Big Think

For over a century, scientists have dreamed of growing human organs sans humans. This technology could put an end to the scarcity of organs for transplants. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The capability to grow fully functional organs would revolutionize research. For example, scientists could observe mysterious biological processes, such as how human cells and organs develop a disease and respond (or fail to respond) to medication without involving human subjects.

Recently, a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge has laid the foundations not just for growing functional organs but functional synthetic embryos capable of developing a beating heart, gut, and brain. Their report was published in Nature.

The organoid revolution

In 1981, scientists discovered how to keep stem cells alive. This was a significant breakthrough, as stem cells have notoriously rigorous demands. Nevertheless, stem cells remained a relatively niche research area, mainly because scientists didn’t know how to convince the cells to turn into other cells.

Then, in 1987, scientists embedded isolated stem cells in a gelatinous protein mixture called Matrigel, which simulated the three-dimensional environment of animal tissue. The cells thrived, but they also did something remarkable: they created breast tissue capable of producing milk proteins. This was the first organoid — a clump of cells that behave and function like a real organ. The organoid revolution had begun, and it all started with a boob in Jello.

For the next 20 years, it was rare to find a scientist who identified as an “organoid researcher,” but there were many “stem cell researchers” who wanted to figure out how to turn stem cells into other cells. Eventually, they discovered the signals (called growth factors) that stem cells require to differentiate into other types of cells.

For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells.

By the end of the 2000s, researchers began combining stem cells, Matrigel, and the newly characterized growth factors to create dozens of organoids, from liver organoids capable of producing the bile salts necessary for digesting fat to brain organoids with components that resemble eyes, the spinal cord, and arguably, the beginnings of sentience.

Synthetic embryos

Organoids possess an intrinsic flaw: they are organ-like. They share some characteristics with real organs, making them powerful tools for research. However, no one has found a way to create an organoid with all the characteristics and functions of a real organ. But Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist, might have set the foundation for that discovery.

Żernicka-Goetz hypothesized that organoids fail to develop into fully functional organs because organs develop as a collective. Organoid research often uses embryonic stem cells, which are the cells from which the developing organism is created. However, there are two other types of stem cells in an early embryo: stem cells that become the placenta and those that become the yolk sac (where the embryo grows and gets its nutrients in early development). For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells. In other words, Żernicka-Goetz suspected the best way to grow a functional organoid was to produce a synthetic embryoid.

As described in the aforementioned Nature paper, Żernicka-Goetz and her team mimicked the embryonic environment by mixing these three types of stem cells from mice. Amazingly, the stem cells self-organized into structures and progressed through the successive developmental stages until they had beating hearts and the foundations of the brain.

“Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart [and] all the components that go on to make up the body,” said Żernicka-Goetz. “It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years and major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it.”

If the methods developed by Żernicka-Goetz’s team are successful with human stem cells, scientists someday could use them to guide the development of synthetic organs for patients awaiting transplants. It also opens the door to studying how embryos develop during pregnancy.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.