To Make Science Engaging, We Need a Sesame Street for Adults

A new kind of television series could establish the baseline narratives for novel science like gene editing, quantum computing, or artificial intelligence.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

In the mid-1960s, a documentary producer in New York City wondered if the addictive jingles, clever visuals, slogans, and repetition of television ads—the ones that were captivating young children of the time—could be harnessed for good. Over the course of three months, she interviewed educators, psychologists, and artists, and the result was a bonanza of ideas.

Perhaps a new TV show could teach children letters and numbers in short animated sequences? Perhaps adults and children could read together with puppets providing comic relief and prompting interaction from the audience? And because it would be broadcast through a device already in almost every home, perhaps this show could reach across socioeconomic divides and close an early education gap?

Soon after Joan Ganz Cooney shared her landmark report, "The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education," in 1966, she was prototyping show ideas, attracting funding from The Carnegie Corporation, The Ford Foundation, and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and co-founding the Children's Television Workshop with psychologist Lloyd Morrisett. And then, on November 10, 1969, informal learning was transformed forever with the premiere of Sesame Street on public television.

For its first season, Sesame Street won three Emmy Awards and a Peabody Award. Its star, Big Bird, landed on the cover of Time Magazine, which called the show "TV's gift to children." Fifty years later, it's hard to imagine an approach to informal preschool learning that isn't Sesame Street.

And that approach can be boiled down to one word: Entertainment.

Despite decades of evidence from Sesame Street—one of the most studied television shows of all time—and more research from social science, psychology, and media communications, we haven't yet taken Ganz Cooney's concepts to heart in educating adults. Adults have news programs and documentaries and educational YouTube channels, but no Sesame Street. So why don't we? Here's how we can design a new kind of television to make science engaging and accessible for a public that is all too often intimidated by it.

We have to start from the realization that America is a nation of high-school graduates. By the end of high school, students have decided to abandon science because they think it's too difficult, and as a nation, we've made it acceptable for any one of us to say "I'm not good at science" and offload thinking to the ones who might be. So, is it surprising that a large number of Americans are likely to believe in conspiracy theories like the 25% that believe the release of COVID-19 was planned, the one in ten who believe the Moon landing was a hoax, or the 30–40% that think the condensation trails of planes are actually nefarious chemtrails? If we're meeting people where they are, the aim can't be to get the audience from an A to an A+, but from an F to a D, and without judgment of where they are starting from.

There's also a natural compulsion for a well-meaning educator to fill a literacy gap with a barrage of information, but this is what I call "factsplaining," and we know it doesn't work. And worse, it can backfire. In one study from 2014, parents were provided with factual information about vaccine safety, and it was the group that was already the most averse to vaccines that uniquely became even more averse.

Why? Our social identities and cognitive biases are stubborn gatekeepers when it comes to processing new information. We filter ideas through pre-existing beliefs—our values, our religions, our political ideologies. Incongruent ideas are rejected. Congruent ideas, no matter how absurd, are allowed through. We hear what we want to hear, and then our brains justify the input by creating narratives that preserve our identities. Even when we have all the facts, we can use them to support any worldview.

But social science has revealed many mechanisms for hijacking these processes through narrative storytelling, and this can form the foundation of a new kind of educational television.

Could new television series establish the baseline narratives for novel science like gene editing, quantum computing, or artificial intelligence?

As media creators, we can reject factsplaining and instead construct entertaining narratives that disrupt cognitive processes. Two-decade-old research tells us when people are immersed in entertaining fiction narratives, they loosen their defenses, opening a path for new information, editing attitudes, and inspiring new behavior. Where news about hot-button issues like climate change or vaccination might trigger resistance or a backfire effect, fiction can be crafted to be absorbing and, as a result, persuasive.

But the narratives can't be stuffed with information. They must be simplified. If this feels like the opposite of what an educator should be doing, it is possible to reduce the complexity of information, without oversimplification, through "exemplification," a framing device to tell the stories of individuals in specific circumstances that can speak to the greater issue without needing to explain it all. It's a technique you've seen used in biopics. The Discovery Channel true-crime miniseries Manhunt: Unabomber does many things well from a science storytelling perspective, including exemplifying the virtues of the scientific method through a character who argues for a new field of science, forensic linguistics, to catch one of the most notorious domestic terrorists in U.S. history.

We must also appeal to the audience's curiosity. We know curiosity is such a strong driver of human behavior that it can even counteract the biases put up by one's political ideology around subjects like climate change. If we treat science information like a product—and we should—advertising research tells us we can maximize curiosity though a Goldilocks effect. If the information is too complex, your show might as well be a PowerPoint presentation. If it's too simple, it's Sesame Street. There's a sweet spot for creating intrigue about new information when there's a moderate cognitive gap.

The science of "identification" tells us that the more the main character is endearing to a viewer, the more likely the viewer will adopt the character's worldview and journey of change. This insight further provides incentives to craft characters reflective of our audiences. If we accept our biases for what they are, we can understand why the messenger becomes more important than the message, because, without an appropriate messenger, the message becomes faint and ineffective. And research confirms that the stereotype-busting doctor-skeptic Dana Scully of The X-Files, a popular science-fiction series, was an inspiration for a generation of women who pursued science careers.

With these directions, we can start making a new kind of television. But is television itself still the right delivery medium? Americans do spend six hours per day—a quarter of their lives—watching video. And even with the rise of social media and apps, science-themed television shows remain popular, with four out of five adults reporting that they watch shows about science at least sometimes. CBS's The Big Bang Theory was the most-watched show on television in the 2017–2018 season, and Cartoon Network's Rick & Morty is the most popular comedy series among millennials. And medical and forensic dramas continue to be broadcast staples. So yes, it's as true today as it was in the 1980s when George Gerbner, the "cultivation theory" researcher who studied the long-term impacts of television images, wrote, "a single episode on primetime television can reach more people than all science and technology promotional efforts put together."

We know from cultivation theory that media images can shape our views of scientists. Quick, picture a scientist! Was it an old, white man with wild hair in a lab coat? If most Americans don't encounter research science firsthand, it's media that dictates how we perceive science and scientists. Characters like Sheldon Cooper and Rick Sanchez become the model. But we can correct that by representing professionals more accurately on-screen and writing characters more like Dana Scully.

Could new television series establish the baseline narratives for novel science like gene editing, quantum computing, or artificial intelligence? Or could new series counter the misinfodemics surrounding COVID-19 and vaccines through more compelling, corrective narratives? Social science has given us a blueprint suggesting they could. Binge-watching a show like the surreal NBC sitcom The Good Place doesn't replace a Ph.D. in philosophy, but its use of humor plants the seed of continued interest in a new subject. The goal of persuasive entertainment isn't to replace formal education, but it can inspire, shift attitudes, increase confidence in the knowledge of complex issues, and otherwise prime viewers for continued learning.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

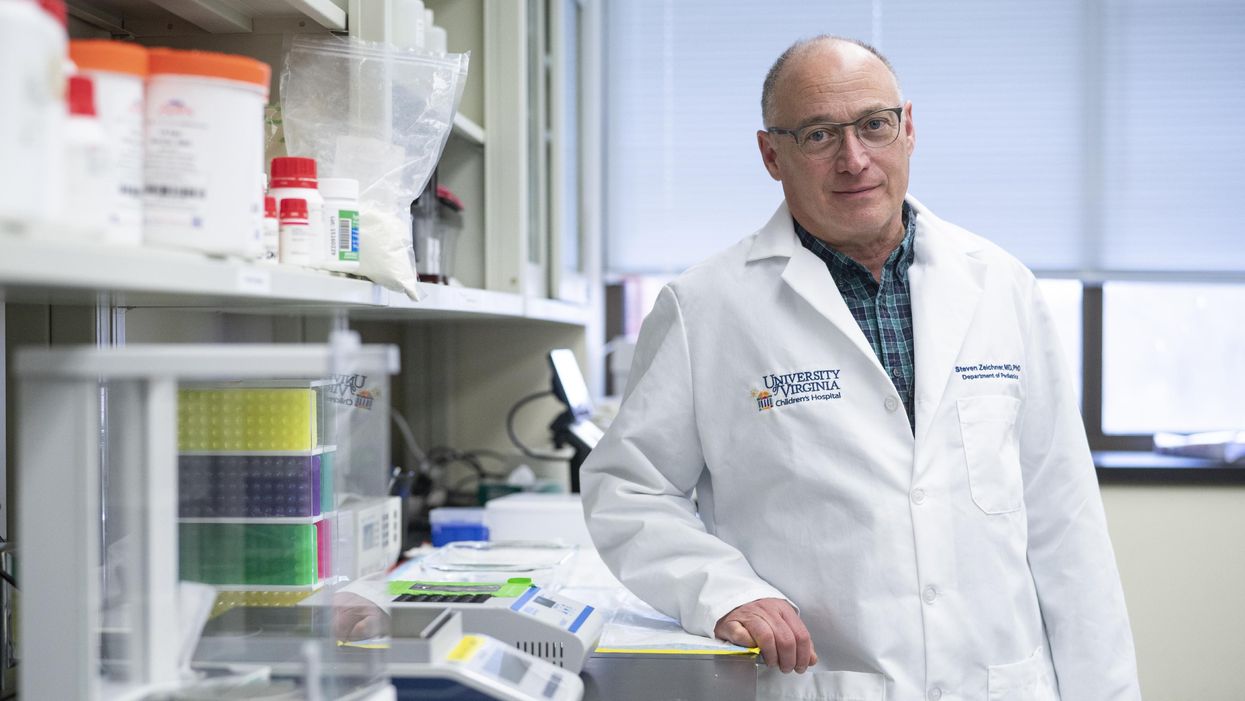

Scientists search for a universal coronavirus vaccine

Stephen Zeichner, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Virginia Medical Center, has made progress with an early stage universal coronavirus vaccine.

The Covid-19 pandemic had barely begun when VBI Vaccines, a biopharmaceutical company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, initiated their search for a universal coronavirus vaccine.

It was March 2020, and while most pharmaceutical companies were scrambling to initiate vaccine programs which specifically targeted the SARS-CoV-2 virus, VBI’s executives were already keen to look at the broader picture.

Having observed the SARS and MERS coronavirus outbreaks over the last two decades, Jeff Baxter, CEO of VBI Vaccines, was aware that SARS-CoV-2 is unlikely to be the last coronavirus to move from an animal host into humans. “It's absolutely apparent that the future is to create a vaccine which gives more broad protection against not only pre-existing coronaviruses, but those that will potentially make the leap into humans in future,” says Baxter.

It was a prescient decision. Over the last two years, more biotechs and pharma companies have joined the search to find a vaccine which might be able to protect against all coronaviruses, along with dozens of academic research groups. Last September, the US National Institutes of Health dedicated $36 million specifically to pan-coronavirus vaccine research, while the global Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has earmarked $200 million towards the effort.

Until October 2021, the very concept of whether it might be

theoretically possible to vaccinate against multiple coronaviruses remained an open question. But then a groundbreaking study renewed optimism.

The emergence of new variants of Covid-19 over the past year, particularly the highly mutated Omicron variant, has added greater impetus to find broader spectrum vaccines. But until October 2021, the very concept of whether it might be theoretically possible to vaccinate against multiple coronaviruses remained an open question. After all, scientists have spent decades trying to develop a similar vaccine for influenza with little success.

But then a groundbreaking study from renowned virologist Linfa Wang, who runs the emerging infectious diseases program at Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, provided renewed optimism.

Wang found that eight SARS survivors who had been injected with the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine had neutralising antibodies in their blood against SARS, the Alpha, Beta and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2, and five other coronaviruses which reside in bats and pangolins. He concluded that the combination of past coronavirus infection, and immunization with a messenger RNA vaccine, had resulted in a wider spectrum of protection than might have been expected.

“This is a significant study because it showed that pre-existing immunity to one coronavirus could help with the elicitation of cross-reactive antibodies when immunizing with a second coronavirus,” says Kevin Saunders, Director of Research at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute in North Carolina, which is developing a universal coronavirus vaccine. “It provides a strategy to perhaps broaden the immune response against coronaviruses.”

In the next few months, some of the first data is set to emerge looking at whether this kind of antibody response could be elicited by a single universal coronavirus vaccine. In April 2021, scientists at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Maryland, launched a Phase I clinical trial of their vaccine, with a spokesman saying that it was successful, and the full results will be announced soon.

The Walter Reed researchers have already released preclinical data, testing the vaccine in non-human primates where it was found to have immunising capabilities against a range of Covid-19 variants as well as the original SARS virus. If the Phase I trial displays similar efficacy, a larger Phase II trial will begin later this year.

Two different approaches

Broadly speaking, scientists are taking two contrasting approaches to the task of finding a universal coronavirus vaccine. The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, VBI Vaccines – who plan to launch their own clinical trial in the summer – and the Duke Human Vaccine Institute – who are launching a Phase I trial in early 2023 – are using a soccer-ball shaped ferritin nanoparticle studded with different coronavirus protein fragments.

VBI Vaccines is looking to elicit broader immune responses by combining SARS, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS spike proteins on the same nanoparticle. Dave Anderson, chief scientific officer at VBI Vaccines, explains that the idea is that by showing the immune system these three spike proteins at the same time, it can help train it to identify and respond to subtle differences between coronavirus strains.

The Duke Human Vaccine Institute is utilising the same method, but rather than including the entire spike proteins from different coronaviruses, they are only including the receptor binding domain (RBD) fragment from each spike protein. “We designed our vaccine to focus the immune system on a site of vulnerability for the virus, which is the receptor binding domain,” says Saunders. “Since the RBD is small, arraying multiple RBDs on a nanoparticle is a straight-forward approach. The goal is to generate immunity to many different subgenuses of viruses so that there will be cross-reactivity with new or unknown coronaviruses.”

But the other strategy is to create a vaccine which contains regions of the viral protein structure which are conserved between all coronavirus strains. This is something which scientists have tried to do for a universal influenza vaccine, but it is thought to be more feasible for coronaviruses because they mutate at a slower rate and are more constrained in the ways that they can evolve.

DIOSynVax, a biotech based in Cambridge, United Kingdom, announced in a press release earlier this month that they are partnering with CEPI to use their computational predictive modelling techniques to identify common structures between all of the SARS coronaviruses which do not mutate, and thus present good vaccine targets.

Stephen Zeichner, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Virginia Medical Center, has created an early stage vaccine using the fusion peptide region – another part of the coronavirus spike protein that aids the virus’s entry into host cells – which so far appears to be highly conserved between all coronaviruses.

So far Zeichner has trialled this version of the vaccine in pigs, where it provided protection against a different coronavirus called porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, which he described as very promising as this virus is from a different family called alphacoronaviruses, while SARS-CoV-2 is a betacoronavirus.

“If a betacoronavirus fusion peptide vaccine designed from SARS-CoV-2 can protect pigs against clinical disease from an alphacoronavirus, then that suggests that an analogous vaccine would enable broad protection against many, many different coronaviruses,” he says.

The road ahead

But while some of the early stage results are promising, researchers are fully aware of the scale of the challenge ahead of them. Although CEPI have declared an aim of having a licensed universal coronavirus vaccine available by 2024-2025, Zeichner says that such timelines are ambitious in the extreme.

“I was incredibly impressed at the speed at which the mRNA coronavirus vaccines were developed for SARS-CoV-2,” he says. “That was faster than just about anybody anticipated. On the other hand, I think a universal coronavirus vaccine is more equivalent to the challenge of developing an HIV vaccine and we're 35 years into that effort without success. We know a lot more now than before, and maybe it will be easier than we think. But I think the route to a universal vaccine is harder than an individual vaccine, so I wouldn’t want to put money on a timeline prediction.”

The major challenge for scientists is essentially designing a vaccine for a future threat which is not even here yet. As such, there are no guidelines on what safety data would be required to license such a vaccine, and how researchers can demonstrate that it truly provides efficacy against all coronaviruses, even those which have not yet jumped to humans.

The teams working on this problem have already devised some ingenious ways of approaching the challenge. VBI Vaccines have taken the genetic sequences of different coronaviruses found in bats and pangolins, from publicly available databases, and inserted them into what virologists call a pseudotype virus – one which has been engineered so it does not have enough genetic material to replicate.

This has allowed them to test the neutralising antibodies that their vaccine produces against these coronaviruses in test tubes, under safe lab conditions. “We have literally just been ordering the sequences, and making synthetic viruses that we can use to test the antibody responses,” says Anderson.

However, some scientists feel that going straight to a universal coronavirus vaccine is likely to be too complex. Instead they say that we should aim for vaccines which are a little more specific. Pamela Bjorkman, a structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology, suggests that pan-coronavirus vaccines which protect against SARS-like betacoronaviruses such as SARS or SARS-CoV-2, or MERS-like betacoronaviruses, may be more realistic.

“I think a vaccine to protect against all coronaviruses is likely impossible since there are so many varieties,” she says. “Perhaps trying to narrow down the scope is advisable.”

But if the mission to develop a universal coronavirus vaccine does succeed, it will be one of the most remarkable feats in the annals of medical science. In January, US chief medical advisor Anthony Fauci urged for greater efforts to be devoted towards this goal, one which scientists feel would be the biological equivalent of the race to develop the first atomic bomb

“The development of an effective universal coronavirus vaccine would be equally groundbreaking, as it would have global applicability and utility,” says Saunders. “Coronaviruses have caused multiple deadly outbreaks, and it is likely that another outbreak will occur. Having a vaccine that prevents death from a future outbreak would be a tremendous achievement in global health.”

He agrees that it will require creativity on a remarkable scale: “The universal coronavirus vaccine will also require ingenuity and perseverance comparable to that needed for the Manhattan project.”

This month, Matt Fuchs becomes the new Editor-in-Chief of Leaps.org.

This month, Kira Peikoff passes the torch to me as editor-in-chief of Leaps.org. I’m excited to assume leadership of this important platform.

Leaps.org caught my eye back in 2018. I was in my late 30s and just starting to wake up to the reality that the people I care most about were getting older and more vulnerable to health problems. At the same time, three critical shifts were becoming impossible to ignore. First, the average age in the U.S. is getting older, a trend known as the “gray tsunami.” Second, healthcare expenses are escalating and becoming unsustainable. And third, our sedentary, stress-filled lifestyles are leading to devastating consequences.

These trends pointed to a future filled with disease, suffering and economic collapse. But whenever I visited Leaps.org, my outlook turned from gloomy to solution-oriented. I became just as fascinated in a fourth trend, one that stands to revolutionize our world: rapid, mind-bending innovations in health and medicine.

Brain atlases, genome sequencing and editing, AI, protein mapping, synthetic biology, 3-D printing—these technologies are yielding new opportunities for health, longevity and human thriving. COVID-19 has caused many setbacks, but it has accelerated scientific breakthroughs. History suggests we will see even more innovation—in digital health and virtual first care, for example—after the pandemic.

In 2020, I began covering these developments with articles for Leaps.org about clocks that measure biological aging, gene therapies for cystic fibrosis, and other seemingly futuristic concepts that are transforming the present. I wrote about them partly because I think most people aren’t aware of them—and meaningful progress can’t happen without public engagement. A broader set of stakeholders and society at large, not just the experts, must inform these changes to ensure that they reflect our values and ethics. Everyone should get the chance to participate in the conversation—and they must have the opportunity to benefit equally from the innovations we decide to move forward with. By highlighting cutting-edge advances, Leaps.org is helping to realize this important goal.

Meanwhile, as I wrote freelance pieces on health and wellness for outlets such as the Washington Post and Time Magazine, I kept seeing an intersect between the breakthroughs in research labs and our expanding knowledge about the science of well-being. Take, for example, emerging technologies designed to stop illnesses in their tracks and new research on the benefits of taking in natural daylight. These two areas, lab innovations and healthy lifestyles, both shift the focus from disease treatment to disease prevention and optimal health. It’s the only sensible, financially feasible way forward.

When Kira suggested that I consider a leadership role with Leaps.org, it struck me how much the platform’s ideals have informed my own perspectives. The frontpage gore of mainstream media outlets can feel like a daily dose of pessimism, with cynicism sometimes dressed up as wisdom. Leaps.org’s world view is rooted in something very different: rational optimism about the present moment and the possibility of human flourishing.

That’s why I’m proud to lead this platform, including our podcast, Making Sense of Science, and hope you’ll keep coming to Leaps.org to learn and join the conversation about scientific gamechangers through our sponsored events, our popular Instagram account and other social channels. Think critically about the breakthroughs and their ethical challenges. Help usher in the health and prosperity that could be ours if we stay open-minded to it.

Yours truly,

Matt Fuchs

Editor-in-Chief