Top Fertility Doctor: Artificially Created Sperm and Eggs "Will Become Normal" One Day

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A rendering of in vitro fertilization.

Imagine two men making a baby. Or two women. Or an infertile couple. Or an older woman whose eggs are no longer viable. None of these people could have a baby today without the help of an egg or sperm donor.

Cells scraped from the inside of your cheek could one day be manipulated to become either eggs or sperm.

But in the future, it may be possible for them to reproduce using only their own genetic material, thanks to an emerging technology called IVG, or in vitro gametogenesis.

Researchers are learning how to reprogram adult human cells like skin cells to become lab-created egg and sperm cells, which could then be joined to form an embryo. In other words, cells scraped from the inside of your cheek could one day be manipulated to become either eggs or sperm, no matter your gender or your reproductive fitness.

In 2016, Japanese scientists proved that the concept could be successfully carried out in mice. Now some experts, like Dr. John Zhang, the founder and CEO of New Hope Fertility Center in Manhattan, say it's just "a matter of time" before the method is also made to work in humans.

Such a technological tour de force would upend our most basic assumptions about human reproduction and biology. Combined with techniques like gene editing, these tools could eventually enable prospective parents to have an unprecedented level of choice and control over their children's origins. It's a wildly controversial notion, and an especially timely one now that a Chinese scientist has announced the birth of the first allegedly CRISPR-edited babies. (The claims remain unverified.)

Zhang himself is no stranger to controversy. In 2016, he stunned the world when he announced the birth of a baby conceived using the DNA of three people, a landmark procedure intended to prevent the baby from inheriting a devastating neurological disease. (Zhang went to a clinic in Mexico to carry out the procedure because it is prohibited in the U.S.) Zhang's other achievements to date include helping a 49-year-old woman have a baby using her own eggs and restoring a young woman's fertility through an ovarian tissue transplant surgery.

Zhang recently sat down with our Editor-in-Chief in his New York office overlooking Columbus Circle to discuss the fertility world's latest provocative developments. Here are his top ten insights:

Clearly [gene-editing embryos] will be beneficial to mankind, but it's a matter of how and when the work is done.

1) On a Chinese scientist's claim of creating the first CRISPR-edited babies:

I'm glad that we made a first move toward a clinical application of this technology for mankind. Somebody has to do this. Whether this was a good case or not, there is still time to find out.

Clearly it will be beneficial to mankind, but it's a matter of how and when the work is done. Like any scientific advance, it has to be done in a very responsible way.

Today's response is identical to when the world's first IVF baby was announced in 1978. The major news media didn't take it seriously and thought it was evil, wanted to keep a distance from IVF. Many countries even abandoned IVF, but today you see it is a normal practice. And it took almost 40 years [for the researchers] to win a Nobel Prize.

I think we need more time to understand how this work was done medically, ethically, and let the scientist have the opportunity to present how it was done and let a scientific journal publish the paper. Before these become available, I don't think we should start being upset, scared, or giving harsh criticism.

2) On the international outcry in response to the news:

I feel we are in scientific shock, with many thinking it came too fast, too soon. We all embrace modern technology, but when something really comes along, we fear it. In an old Chinese saying, one of the masters always dreamed of seeing the dragon, and when the dragon really came, he got scared.

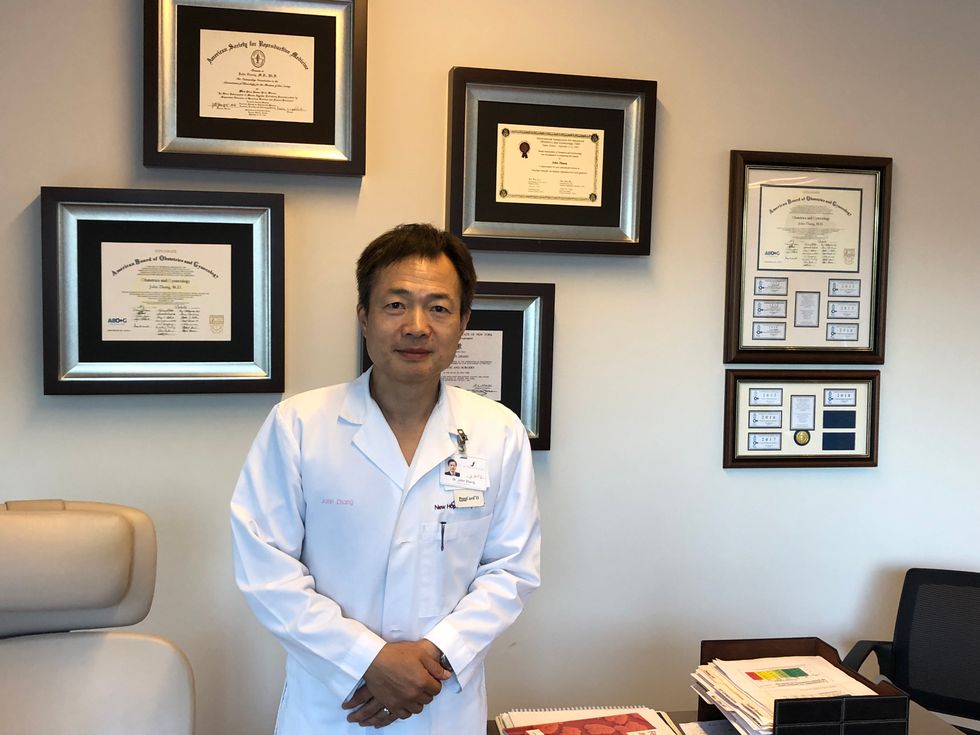

Dr. John Zhang, the founder and CEO of New Hope Fertility Center in Manhattan, pictured in his office.

3) On the Western world's perception that Chinese scientists sometimes appear to discount ethics in favor of speedy breakthroughs:

I think this perception is not fair. I don't think China is very casual. It's absolutely not what people think. I don't want people to feel that this case [of CRISPR-edited babies] will mean China has less standards over how human reproduction should be performed. Just because this happened, it doesn't mean in China you can do anything you want.

As far as the regulation of IVF clinics, China is probably the most strictly regulated of any country I know in this world.

4) On China's first public opinion poll gauging attitudes toward gene-edited babies, indicating that more than 60 percent of survey respondents supported using the technology to prevent inherited diseases, but not to enhance traits:

There is a sharp contrast between the general public and the professional world. Being a working health professional and an advocate of scientists working in this field, it is very important to be ethically responsible for what we are doing, but my own feeling is that from time to time we may not take into consideration what the patient needs.

5) On how the three-parent baby is doing today, several years after his birth:

No news is good news.

6) On the potentially game-changing research to develop artificial sperm and eggs:

First of all I think that anything that's technically possible, as long as you are not harmful to other people, to other societies, as long as you do it responsibly, and this is a legitimate desire, I think eventually it will become reality.

My research for now is really to try to overcome the very next obstacle in our field, which is how to let a lady age 44 or older have a baby with her own genetic material.

Practically 99 percent of women over age 43 will never make a baby on their own. And after age 47, we usually don't offer donor egg IVF anymore.

But with improved longevity, and quality of life, the lifespan of females continues to increase. In Japan, the average for females is about 89 years old. So for more than half of your life, you will not be able to produce a baby, which is quite significant in the animal kingdom. In most of the animal kingdom, their reproductive life is very much the same as their life, but then you can argue in the animal kingdom unlike a human being, it doesn't take such a long time for them to contribute to the society because once you know how to hunt and look for food, you're done.

"I think this will become a major ethical debate: whether we should let an older lady have a baby at a very late state of her life."

But humans are different. You need to go to college, get certain skills. It takes 20 years to really bring a human being up to become useful to society. That's why the mom and dad are not supposed to have the same reproductive life equal to their real life.

I think this will become a major ethical debate: whether we should let an older lady have a baby at a very late state of her life and leave the future generation in a very vulnerable situation in which they may lack warm caring, proper guidance, and proper education.

7) On using artificial gametes to grant more reproductive choices to gays and lesbians:

I think it is totally possible to have two sperm make a baby, and two eggs make babies.

If we have two guys, one guy to produce eggs, or two girls, one would have to become sperm. Basically you are creating artificial gametes or converting with gametes from sperm to become egg or egg to become a sperm. Which may not necessarily be very difficult. The key is to be able to do nuclear reprogramming.

So why can two sperm not make offspring now? You get exactly half of your genes from each parent. The genes have their own imprinting that say "made in mom," "made in dad." The two sperm would say "made in dad," "made in dad." If I can erase the "made in dad," and say "made in mom," then these sperm can make offspring.

8) On how close science is to creating artificial gametes for clinical use in pregnancies:

It's very hard to say until we accomplish it. It could be very quick. It could be it takes a long time. I don't want to speculate.

"I think these technologies are the solid foundation just like when we designed the computer -- we never thought a computer would become the iPhone."

9) On whether there should be ethical red lines drawn by authorities or whether the decisions should be left to patients and scientists:

I think we cannot believe a hundred percent in the scientist and the patient but it should not be 100 percent authority. It should be coming from the whole of society.

10) On his expectations for the future:

We are living in a very exciting world. I think that all these technologies can really change the way of mankind and also are not just for baby-making. The research, the experience, the mechanism we learn from these technologies, they will shine some great lights into our long-held dream of being a healthy population that is cancer-free and lives a long life, let's say 120 years.

I think these technologies are the solid foundation just like when we designed the computer -- we never thought a computer would become the iPhone. Imagine making a computer 30 years ago, that this little chip will change your life.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

In this week's Friday Five, attending sports events is linked to greater life satisfaction, AI can identify specific brain tumors in under 90 seconds, LSD - minus hallucinations - raises hopes for mental health, new research on the benefits of cold showers, and inspiring awe in your kids leads to behavior change.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on new scientific theories and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

This episode includes an interview with Dr. Helen Keyes, Head of the School of Psychology and Sports Science at Anglia Ruskin University.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

- Attending sports events is linked to greater life satisfaction

- Identifying specific brain tumors in under 90 seconds with AI

- LSD - minus hallucinations - raises hopes for mental health

- New research on the benefits of cold showers

- Inspire awe in your kids and reap the benefits

Residents of Fountain Hills, a small town near Phoenix, Arizona, fought against the night sky pollution to restore their Milky Way skies.

As a graduate student in observational astronomy at the University of Arizona during the 1970s, Diane Turnshek remembers the starry skies above the Kitt Peak National Observatory on the Tucson outskirts. Back then, she could observe faint objects like nebulae, galaxies, and star clusters on most nights.

When Turnshek moved to Pittsburgh in 1981, she found it almost impossible to see a clear night sky because the city’s countless lights created a bright dome of light called skyglow. Over the next two decades, Turnshek almost forgot what a dark sky looked like. She witnessed pristine dark skies in their full glory again during a visit to the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah in early 2000s.

“I was shocked at how beautiful the dark skies were in the West. That is when I realized that most parts of the world have lost access to starry skies because of light pollution,” says Turnshek, an astronomer and lecturer at Carnegie Mellon University. In 2015, she became a dark sky advocate.

Light pollution is defined as the excessive or wasteful use of artificial light.

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) -- which became commercially available in 2002 and rapidly gained popularity in offices, schools, and hospitals when their price dropped six years later — inadvertently fueled the surge in light pollution. As traditional light sources like halogen, fluorescent, mercury, and sodium vapor lamps have been phased out or banned, LEDs became the main source of lighting globally in 2019. Switching to LEDs has been lauded as a win-win decision. Not only are they cheap but they also consume a fraction of electricity compared to their traditional counterparts.

But as cheap LED installations became omnipresent, they increased light pollution. “People have been installing LEDs thinking they are making a positive change for the environment. But LEDs are a lot brighter than traditional light sources,” explains Ashley Wilson, director of conservation at the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA). “Despite being energy-efficient, they are increasing our energy consumption. No one expected this kind of backlash from switching to LEDs.”

Light pollution impacts the circadian rhythms of all living beings — the natural internal process that regulates the sleep–wake cycle.

Currently, more than 80 percent of the world lives under light-polluted skies. In the U.S. and Europe, that figure is above 99 percent.

According to the IDA, $3 billion worth of electricity is lost to skyglow every year in the U.S. alone — thanks to unnecessary and poorly designed outdoor lighting installations. Worse, the resulting light pollution has insidious impacts on humans and wildlife — in more ways than one.

Disrupting the brain’s clock

Light pollution impacts the circadian rhythms of all living beings—the natural internal process that regulates the sleep–wake cycle. Humans and other mammals have neurons in their retina called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs). These cells collect information about the visual world and directly influence the brain’s biological clock in the hypothalamus.

The ipRGCs are particularly sensitive to the blue light that LEDs emit at high levels, resulting in suppression of melatonin, a hormone that helps us sleep. A 2020 JAMA Psychiatry study detailed how teenagers who lived in areas with bright outdoor lighting at night went to bed late and slept less, which made them more prone to mood disorders and anxiety.

“Many people are skeptical when they are told something as ubiquitous as lights could have such profound impacts on public health,” says Gena Glickman, director of the Chronobiology, Light and Sleep Lab at Uniformed Services University. “But when the clock in our brains gets exposed to blue light at nighttime, it could result in a lot of negative consequences like impaired cognitive function and neuro-endocrine disturbances.”

In the last 12 years, several studies indicated that light pollution exposure is associated with obesity and diabetes in humans and animals alike. While researchers are still trying to understand the exact underlying mechanisms, they found that even one night of too much light exposure could negatively affect the metabolic system. Studies have linked light pollution to a higher risk of hormone-sensitive cancers like breast and prostate cancer. A 2017 study found that female nurses exposed to light pollution have a 14 percent higher risk of breast cancer. The World Health Organization (WHO) identified long-term night shiftwork as a probable cause of cancer.

“We ignore our biological need for a natural light and dark cycle. Our patterns of light exposure have consequently become different from what nature intended,” explains Glickman.

Circadian lighting systems, designed to match individuals’ circadian rhythms, might help. The Lighting Research Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute developed LED light systems that mimic natural lighting fluxes, required for better sleep. In the morning the lights shine brightly as does the sun. After sunset, the system dims, once again mimicking nature, which boosts melatonin production. It can even be programmed to increase blue light indoors when clouds block sunlight’s path through windows. Studies have shown that such systems might help reduce sleep fragmentation and cognitive decline. People who spend most of their day indoors can benefit from such circadian mimics.

When Diane Turnshek moved to Pittsburgh, she found it almost impossible to see a clear night sky because the city’s countless lights created a bright dome of light called skyglow.

Diane Turnshek

Leading to better LEDs

Light pollution disrupts the travels of millions of migratory birds that begin their long-distance journeys after sunset but end up entrapped within the sky glow of cities, becoming disoriented. A 2017 study in Nature found that nocturnal pollinators like bees, moths, fireflies and bats visit 62 percent fewer plants in areas with artificial lights compared to dark areas.

“On an evolutionary timescale, LEDs have triggered huge changes in the Earth’s environment within a relative blink of an eye,” says Wilson, the director of IDA. “Plants and animals cannot adapt so fast. They have to fight to survive with their existing traits and abilities.”

But not all types of LEDs are inherently bad -- it all comes down to how much blue light they emit. During the day, the sun emits blue light waves. By sunset, red and orange light waves become predominant, stimulating melatonin production. LED’s artificial blue light, when shining at night, disrupts that. For some unknown reason, there are more bluer color LEDs made and sold.

“Communities install blue color temperature LEDs rather than redder color temperature LEDs because more of the blue ones are made; they are the status quo on the market,” says Michelle Wooten, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Most artificial outdoor light produced is wasted as human eyes do not use them to navigate their surroundings.

While astronomers and the IDA have been educating LED manufacturers about these nuances, policymakers struggle to keep up with the growing industry. But there are things they can do—such as requiring LEDs to include dimmers. “Most LED installations can be dimmed down. We need to make the dimmable drivers a mandatory requirement while selling LED lighting,” says Nancy Clanton, a lighting engineer, designer, and dark sky advocate.

Some lighting companies have been developing more sophisticated LED lights that help support melatonin production. Lighting engineers at Crossroads LLC and Nichia Corporation have been working on creating LEDs that produce more light in the red range. “We live in a wonderful age of technology that has given us these new LED designs which cut out blue wavelengths entirely for dark-sky friendly lighting purposes,” says Wooten.

Dimming the lights to see better

The IDA and advocates like Turnshek propose that communities turn off unnecessary outdoor lights. According to the Department of Energy, 99 percent of artificial outdoor light produced is wasted as human eyes do not use them to navigate their surroundings.

In recent years, major cities like Chicago, Austin, and Philadelphia adopted the “Lights Out” initiative encouraging communities to turn off unnecessary lights during birds’ peak migration seasons for 10 days at a time. “This poses an important question: if people can live without some lights for 10 days, why can’t they keep them turned off all year round,” says Wilson.

Most communities globally believe that keeping bright outdoor lights on all night increases security and prevents crime. But in her studies of street lights’ brightness levels in different parts of the US — from Alaska to California to Washington — Clanton found that people felt safe and could see clearly even at low or dim lighting levels.

Clanton and colleagues installed LEDs in a Seattle suburb that provided only 25 percent of lighting levels compared to what they used previously. The residents reported far better visibility because the new LEDs did not produce glare. “Visual contrast matters a lot more than lighting levels,” Clanton says. Additionally, motion sensor LEDs for outdoor lighting can go a long way in reducing light pollution.

Flipping a switch to preserve starry nights

Clanton has helped draft laws to reduce light pollution in at least 17 U.S. states. However, poor awareness of light pollution led to inadequate enforcement of these laws. Also, getting thousands of counties and municipalities within any state to comply with these regulations is a Herculean task, Turnshek points out.

Fountain Hills, a small town near Phoenix, Arizona, has rid itself of light pollution since 2018, thanks to the community's efforts to preserve dark skies.

Until LEDs became mainstream, Fountain Hills enjoyed starry skies despite its proximity to Phoenix. A mountain surrounding the town blocks most of the skyglow from the city.

“Light pollution became an issue in Fountain Hills over the years because we were not taking new LED technologies into account. Our town’s lighting code was antiquated and out-of-date,” says Vicky Derksen, a resident who is also a part of the Fountain Hills Dark Sky Association founded in 2017. “To preserve dark skies, we had to work with the entire town to update the local lighting code and convince residents to follow responsible outdoor lighting practices.”

Derksen and her team first tackled light pollution in the town center which has a faux fountain in the middle of a lake. “The iconic centerpiece, from which Fountain Hills got its name, had the wrong types of lighting fixtures, which created a lot of glare,” adds Derksen. They then replaced several other municipal lighting fixtures with dark-sky-friendly LEDs.

The results were awe-inspiring. After a long time, residents could see the Milky Way with crystal clear clarity. Star-gazing activities made a strong comeback across the town. But keeping light pollution low requires constant work.

Derksen and other residents regularly measure artificial light levels in

Fountain Hills. Currently, the only major source of light pollution is from extremely bright, illuminated signs which local businesses had installed in different parts of the town. While Derksen says it is an uphill battle to educate local businesses about light pollution, Fountain Hills residents are determined to protect their dark skies.

“When a river gets polluted, it can take several years before clean-up efforts see any tangible results,” says Derksen. “But the effects are immediate when you work toward reducing light pollution. All it requires is flipping a switch.”