New drug for schizophrenia could meet desperate need for better treatments

The field of treating schizophrenia with drugs has been stuck in a long drought but, this month, a late-stage clinical trial found a new drug called KarXT could treat a range of symptoms.

Schizophrenia is a debilitating mental health condition that affects around 24 million people worldwide. Patients experience hallucinations and delusions when they develop schizophrenia, with experts referring to these new thoughts and behaviors as positive symptoms. They also suffer from negative symptoms in which they lose important functions, suffering from dulled emotions, lack of purpose and social withdrawal.

Currently available drugs can control only a portion of these symptoms but, on August 8th, Karuna Therapeutics announced its completion of a phase 3 clinical trial that found a new drug called KarXT could treat both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It could mean substantial progress against a problem that has stymied scientists for decades.

A long-standing problem

Since the 1950s, antipsychotics have been used to treat schizophrenia. People who suffer from it are thought to have too much of a brain chemical called dopamine, and antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine receptors in the brain. They can be effective in treating positive symptoms but have little impact on the negative ones, which can be devastating for a patient’s quality of life, making it difficult to maintain employment and have successful relationships. About 30 percent of schizophrenia patients don't actually respond to antipsychotics at all. Current drugs can also have adverse side effects including elevated cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes and movements that patients cannot control.

The recent clinical trial heralds a new treatment approach. “We believe it marks an important advancement for patients given its new and completely different mechanism of action from current therapies,” says Andrew Miller, COO of Karuna.

Scientists have been looking to develop alternatives. However, “the field of drug treatment of schizophrenia is currently in the doldrums,” says Peter McKenna, a senior researcher at FIDMAG Research Foundation in Spain which specialises in mental health.

In the 2000s there was a major push to target a brain receptor for a chemical called glutamate. Evidence suggested that this receptor is abnormal in the brains of schizophrenia patients, but attempts to try glutamate failed in clinical trials.

After that, many pharmaceutical companies dropped out of the race for a more useful treatment. But some companies continued to search, such as Karuna Therapeutics, led by founder and Chief Operating Officer Andrew Miller and CEO Steve Paul. The recent clinical trial suggests their persistence has led to an important breakthrough with their drug, KarXT. “We believe it marks an important advancement for patients given its new and completely different mechanism of action from current therapies,” Miller says.

How it works

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that pass signals between neurons. To work effectively, neurotransmitters need a receptor to bind to. A neurotransmitter called acetylcholine seems to be especially important in schizophrenia. It interacts with sites called muscarinic receptors, which are involved in the network of nerves that calm your body after a stressful event. Post mortem studies in people with schizophrenia have shown that two muscarinic receptors in the brain, the M1 and M4 receptors, are activated at unusually low levels because they don’t receive enough signals from acetylcholine.

The M4 receptor appears to play a role in psychosis. The M1 receptor is also associated with psychosis but is primarily thought to be involved in cognition. KarXT, taken orally, works by activating both of these receptors to signal properly. It is this twofold action that seems to explain its effectiveness. “[The drug’s] design enables the preferential stimulation of these muscarinic receptors in the brain,” Miller says.

How it developed

It all started in the early 1990s when Paul was at pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly. He discovered that Xanomeline, the drug they were testing on Alzheimer's patients, had antipsychotic effects. It worked by stimulating M1 and M4 receptors, so he and his colleagues decided to test Xanomeline on schizophrenia patients, supported by research on the connection between muscarinic receptors and psychosis. They found that Xanomeline reduced both positive and negative symptoms.

Unfortunately, it also caused significant side effects. The problem was that stimulating the M1 and M4 receptors in the brain also stimulated muscarinic receptors in the body that led to severe vomiting, diarrhea and even the temporary loss of consciousness.

In the end, Eli Lilly discontinued the clinical trials for the drug, but Miller set up Karuna Therapeutics to develop a solution. “I was determined to find a way to harness the therapeutic benefit demonstrated in studies of Xanomeline, while eliminating side effects that limited its development,” Miller says.

He analysed over 7,000 possible ways of mixing Xanomeline with other agents before settling on KarXT. It combines Xanomeline with a drug called Trospium Chloride, which blocks muscarinic receptors in the body – taking care of the side effects such as vomiting – but leaves them unblocked in the brain. Paul was so excited by Miller’s progress that he joined Karuna after leaving Eli Lilly and founding two previous startups.

“It's a very important approach,” says Rick Adams, Future Leaders Fellow in the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Centre for Medical Image Computing at University College London. “We are in desperate need of alternative drug targets and this target is one of the best. There are other alternative targets, but not many are as close to being successful as the muscarinic receptor drug.”

Clinical Trial

Following a successful phase 2 clinical trial in 2019, the most recent trial involved 126 patients who were given KarXT, and 126 who were given a placebo. Compared to the placebo, patients taking KarXT had a significant 9.6 point reduction in the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS), the standard for rating schizophrenic symptoms.

KarXT also led to statistically significant declines in positive and negative symptoms compared to the placebo. “The results suggest that KarXT could be a potentially game-changing option in the management of both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia,” Miller says.

Robert McCutcheon, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Oxford University, is optimistic about the side effects but highlights the need for more safety trials.

McKenna, the researcher at FIDMAG Foundation, agrees about the drug’s potential. “The new [phase 3] study is positive,” he says. “It is reassuring that one is not dealing with a drug that works in one trial and then inexplicably fails in the next one.”

Robert McCutcheon, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Oxford University, said the drug is an unprecedented step forward. “KarXT is one of the first drugs with a novel mechanism of action to show promise in clinical trials.”

Even though the drug blocks muscarine receptors in the body, some patients still suffered from adverse side effects like vomiting, dizziness and diarrhea. But in general, these effects were mild to moderate, especially compared to dopamine-blocking antipsychotics or Xanomeline on its own.

McCutcheon is optimistic about the side effects but highlights the need for more safety trials. “The trial results suggest that gastrointestinal side effects appear to be manageable,” he says. “We know, however, from previous antipsychotic drugs that the full picture regarding the extent of side effects can sometimes take longer to become apparent to clinicians and patients. Careful ongoing assessment during a longer period of treatment will therefore be important.”

The Future

The team is currently conducting three other trials to evaluate the efficacy and long-term safety of KarXT. Their goal is to receive FDA approval next year.

Karuna is also conducting trials to evaluate the effectiveness of KarXT in treating psychosis in patients suffering from Alzheimer’s.

The big hope is that they will soon be able to provide a radically different drug to help many patients with schizophrenia. “We are another step closer to potentially providing the first new class of medicine in more than 50 years to the millions of people worldwide living with schizophrenia,” says Miller.

Researchers are looking to engineer chocolate with less oil, which could reduce some of its detriments to health.

Creamy milk with velvety texture. Dark with sprinkles of sea salt. Crunchy hazelnut-studded chunks. Chocolate is a treat that appeals to billions of people worldwide, no matter the age. And it’s not only the taste, but the feel of a chocolate morsel slowly melting in our mouths—the smoothness and slipperiness—that’s part of the overwhelming satisfaction. Why is it so enjoyable?

That’s what an interdisciplinary research team of chocolate lovers from the University of Leeds School of Food Science and Nutrition and School of Mechanical Engineering in the U.K. resolved to study in 2021. They wanted to know, “What is making chocolate that desirable?” says Siavash Soltanahmadi, one of the lead authors of a new study about chocolates hedonistic quality.

Besides addressing the researchers’ general curiosity, their answers might help chocolate manufacturers make the delicacy even more enjoyable and potentially healthier. After all, chocolate is a billion-dollar industry. Revenue from chocolate sales, whether milk or dark, is forecasted to grow 13 percent by 2027 in the U.K. In the U.S., chocolate and candy sales increased by 11 percent from 2020 to 2021, on track to reach $44.9 billion by 2026. Figuring out how chocolate affects the human palate could up the ante even more.

Building a 3D tongue

The team began by building a 3D tongue to analyze the physical process by which chocolate breaks down inside the mouth.

As part of the effort, reported earlier this year in the scientific journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, the team studied a large variety of human tongues with the intention to build an “average” 3D model, says Soltanahmadi, a lubrication scientist. When it comes to edible substances, lubrication science looks at how food feels in the mouth and can help design foods that taste better and have more satisfying texture or health benefits.

There are variations in how people enjoy chocolate; some chew it while others “lick it” inside their mouths.

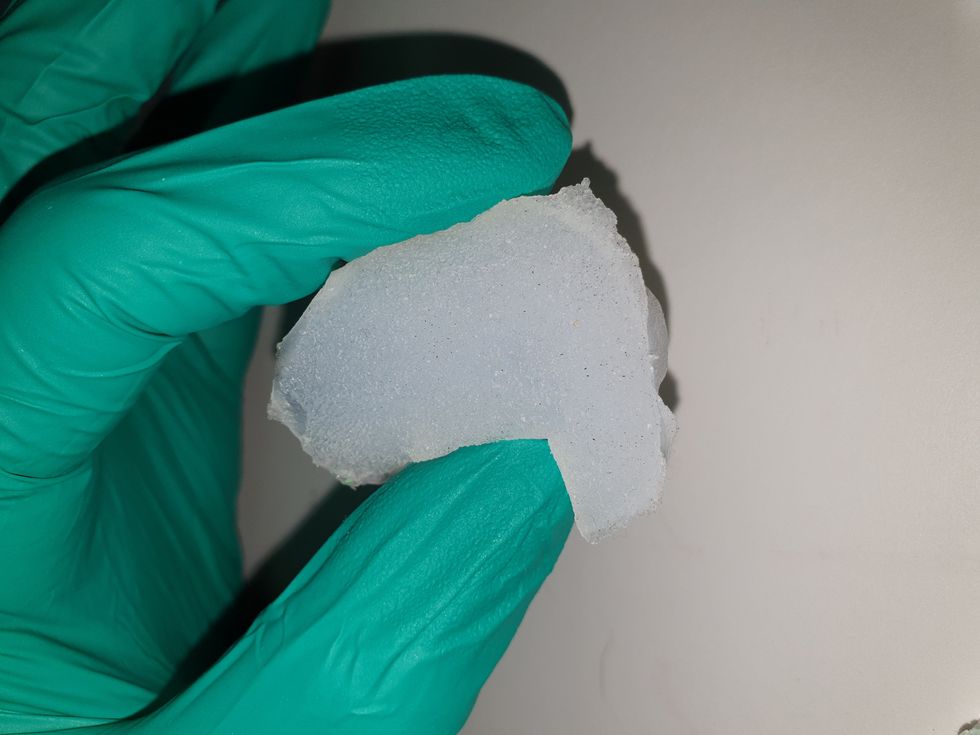

Tongue impressions from human participants studied using optical imaging helped the team build a tongue with key characteristics. “Our tongue is not a smooth muscle, it’s got some texture, it has got some roughness,” Soltanahmadi says. From those images, the team came up with a digital design of an average tongue and, using 3D printed molds, built a “mimic tongue.” They also added elastomers—such as silicone or polyurethane—to mimic the roughness, the texture and the mechanical properties of a real tongue. “Wettability" was another key component of the 3D tongue, Soltanahmadi says, referring to whether a surface mixes with water (hydrophilic) or, in the case of oil, resists it (hydrophobic).

Notably, the resulting artificial 3D-tongues looked nothing like the human version, but they were good mimics. The scientists also created “testing kits” that produced data on various physical parameters. One such parameter was viscosity, the measure of how gooey a food or liquid is — honey is more viscous compared to water, for example. Another was tribology, which defines how slippery something is — high fat yogurt is more slippery than low fat yogurt; milk can be more slippery than water. The researchers then mixed chocolate with artificial saliva and spread it on the 3D tongue to measure the tribology and the viscosity. From there they were able to study what happens inside the mouth when we eat chocolate.

The team focused on the stages of lubrication and the location of the fat in the chocolate, a process that has rarely been researched.

The artificial 3D-tongues look nothing like human tongues, but they function well enough to do the job.

Courtesy Anwesha Sarkar and University of Leeds

The oral processing of chocolate

We process food in our mouths in several stages, Soltanahmadi says. And there is variation in these stages depending on the type of food. So, the oral processing of a piece of meat would be different from, say, the processing of jelly or popcorn.

There are variations with chocolate, in particular; some people chew it while others use their tongues to explore it (within their mouths), Soltanahmadi explains. “Usually, from a consumer perspective, what we find is that if you have a luxury kind of a chocolate, then people tend to start with licking the chocolate rather than chewing it.” The researchers used a luxury brand of dark chocolate and focused on the process of licking rather than chewing.

As solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave.

Understanding the make-up of the chocolate was also an important step in the study. “Chocolate is a composite material. So, it has cocoa butter, which is oil, it has some particles in it, which is cocoa solid, and it has sugars," Soltanahmadi says. "Dark chocolate has less oil, for example, and less sugar in it, most of the time."

The researchers determined that the oral processing of chocolate begins as soon as it enters a person’s mouth; it starts melting upon exposure to one’s body temperature, even before the tongue starts moving, Soltanahmadi says. Then, lubrication begins. “[Saliva] mixes with the oily chocolate and it makes an emulsion." An emulsion is a fluid with a watery (or aqueous) phase and an oily phase. As chocolate breaks down in the mouth, that solid piece turns into a smooth emulsion with a fatty film. “The oil from the chocolate becomes droplets in a continuous aqueous phase,” says Soltanahmadi. In other words, as solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette, creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave, says Soltanahmadi.

Finding the sweet spot

After determining how chocolate is orally processed, the research team wanted to find the exact sweet spot of the breakdown of solid cocoa particles and fat as they are released into the mouth. They determined that the epicurean pleasure comes only from the chocolate's outer layer of fat; the secondary fatty layers inside the chocolate don’t add to the sensation. It was this final discovery that helped the team determine that it might be possible to produce healthier chocolate that would contain less oil, says Soltanahmadi. And therefore, less fat.

Rongjia Tao, a physicist at Temple University in Philadelphia, thinks the Leeds study and the concept behind it is “very interesting.” Tao, himself, did a study in 2016 and found he could reduce fat in milk chocolate by 20 percent. He believes that the Leeds researchers’ discovery about the first layer of fat being more important for taste than the other layer can inform future chocolate manufacturing. “As a scientist I consider this significant and an important starting point,” he says.

Chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research found that plant polyphenols can protect against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular ad neurodegenerative diseases.

Not everyone thinks it’s a good idea, such as chef Michael Antonorsi, founder and owner of Chuao Chocolatier, one of the leading chocolate makers in the U.S. First, he says, “cacao fat is definitely a good fat.” Second, he’s not thrilled that science is trying to interfere with nature. “Every time we've tried to intervene and change nature, we get things out of balance,” says Antonorsi. “There’s a reason cacao is botanically known as food of the gods. The botanical name is the Theobroma cacao: Theobroma in ancient Greek, Theo is God and Brahma is food. So it's a food of the gods,” Antonorsi explains. He’s doubtful that a chocolate made only with a top layer of fat will produce the same epicurean satisfaction. “You're not going to achieve the same sensation because that surface fat is going to dissipate and there is no fat from behind coming to take over,” he says.

Without layers of fat, Antonorsi fears the deeply satisfying experiential part of savoring chocolate will be lost. The University of Leeds team, however, thinks that it may be possible to make chocolate healthier - when consumed in limited amounts - without sacrificing its taste. They believe the concept of less fatty but no less slick chocolate will resonate with at least some chocolate-makers and consumers, too.

Chocolate already contains some healthful compounds. Its cocoa particles have “loads of health benefits,” says Soltanahmadi. Dark chocolate usually has more cocoa than milk chocolate. Some experts recommend that dark chocolate should contain at least 70 percent cocoa in order for it to offer some health benefit. Research has shown that the cocoa in chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research has shown that consuming plant polyphenols can be protective against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

“So keeping the healthy part of it and reducing the oily part of it, which is not healthy, but is giving you that indulgence of it … that was the final aim,” Soltanahmadi says. He adds that the team has been approached by individuals in the chocolate industry about their research. “Everyone wants to have a healthy chocolate, which at the same time tastes brilliant and gives you that self-indulging experience.”

Probiotic bacteria can be engineered to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs by releasing chemicals that kill them.

In 1945, almost two decades after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, he warned that as antibiotics use grows, they may lose their efficiency. He was prescient—the first case of penicillin resistance was reported two years later. Back then, not many people paid attention to Fleming’s warning. After all, the “golden era” of the antibiotics age had just began. By the 1950s, three new antibiotics derived from soil bacteria — streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline — could cure infectious diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, meningitis and typhoid fever, among others.

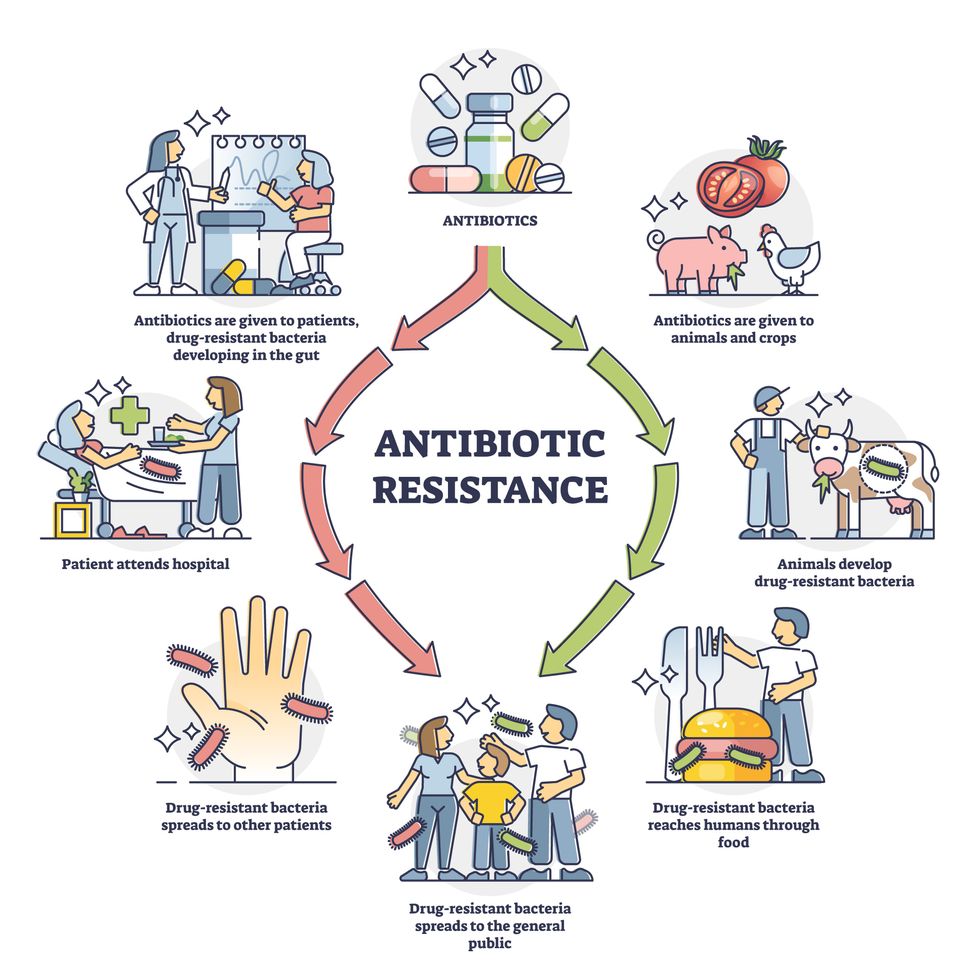

Today, these antibiotics and many of their successors developed through the 1980s are gradually losing their effectiveness. The extensive overuse and misuse of antibiotics led to the rise of drug resistance. The livestock sector buys around 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. every year. Farmers feed cows and chickens low doses of antibiotics to prevent infections and fatten up the animals, which eventually causes resistant bacterial strains to evolve. If manure from cattle is used on fields, the soil and vegetables can get contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Another major factor is doctors overprescribing antibiotics to humans, particularly in low-income countries. Between 2000 to 2018, the global rates of human antibiotic consumption shot up by 46 percent.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring a promising avenue: the use of synthetic biology to engineer new bacteria that may work better than antibiotics. The need continues to grow, as a Lancet study linked antibiotic resistance to over 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria. The western sub-Saharan Africa region had the highest death rate (27.3 people per 100,000).

Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

To make it worse, our remedy pipelines are drying up. Out of the 18 biggest pharmaceutical companies, 15 abandoned antibiotic development by 2013. According to the AMR Action Fund, venture capital has remained indifferent towards biotech start-ups developing new antibiotics. In 2019, at least two antibiotic start-ups filed for bankruptcy. As of December 2020, there were 43 new antibiotics in clinical development. But because they are based on previously known molecules, scientists say they are inadequate for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria. Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

The rise of synthetic biology

To circumvent this dire future, scientists have been working on alternative solutions using synthetic biology tools, meaning genetically modifying good bacteria to fight the bad ones.

From the time life evolved on earth around 3.8 billion years ago, bacteria have engaged in biological warfare. They constantly strategize new methods to combat each other by synthesizing toxic proteins that kill competition.

For example, Escherichia coli produces bacteriocins or toxins to kill other strains of E.coli that attempt to colonize the same habitat. Microbes like E.coli (which are not all pathogenic) are also naturally present in the human microbiome. The human microbiome harbors up to 100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells. The majority of them are beneficial organisms residing in the gut at different compositions.

The chemicals that these “good bacteria” produce do not pose any health risks to us, but can be toxic to other bacteria, particularly to human pathogens. For the last three decades, scientists have been manipulating bacteria’s biological warfare tactics to our collective advantage.

In the late 1990s, researchers drew inspiration from electrical and computing engineering principles that involve constructing digital circuits to control devices. In certain ways, every cell in living organisms works like a tiny computer. The cell receives messages in the form of biochemical molecules that cling on to its surface. Those messages get processed within the cells through a series of complex molecular interactions.

Synthetic biologists can harness these living cells’ information processing skills and use them to construct genetic circuits that perform specific instructions—for example, secrete a toxin that kills pathogenic bacteria. “Any synthetic genetic circuit is merely a piece of information that hangs around in the bacteria’s cytoplasm,” explains José Rubén Morones-Ramírez, a professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico. Then the ribosome, which synthesizes proteins in the cell, processes that new information, making the compounds scientists want bacteria to make. “The genetic circuit remains separated from the living cell’s DNA,” Morones-Ramírez explains. When the engineered bacteria replicates, the genetic circuit doesn’t become part of its genome.

Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut.

In 2000, Boston-based researchers constructed an E.coli with a genetic switch that toggled between turning genes on and off two. Later, they built some safety checks into their bacteria. “To prevent unintentional or deleterious consequences, in 2009, we built a safety switch in the engineered bacteria’s genetic circuit that gets triggered after it gets exposed to a pathogen," says James Collins, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and faculty member at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “After getting rid of the pathogen, the engineered bacteria is designed to switch off and leave the patient's body.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics causes resistant strains to evolve

Adobe Stock

Seek and destroy

As the field of synthetic biology developed, scientists began using engineered bacteria to tackle superbugs. They first focused on Vibrio cholerae, which in the 19th and 20th century caused cholera pandemics in India, China, the Middle East, Europe, and Americas. Like many other bacteria, V. cholerae communicate with each other via quorum sensing, a process in which the microorganisms release different signaling molecules, to convey messages to its brethren. Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut. When untreated, cholera has a mortality rate of 25 to 50 percent and outbreaks frequently occur in developing countries, especially during floods and droughts.

Sometimes, however, V. cholerae makes mistakes. In 2008, researchers at Cornell University observed that when quorum sensing V. cholerae accidentally released high concentrations of a signaling molecule called CAI-1, it had a counterproductive effect—the pathogen couldn’t colonize the gut.

So the group, led by John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering, developed a novel strategy to combat V. cholerae. They genetically engineered E.coli to eavesdrop on V. cholerae communication networks and equipped it with the ability to release the CAI-1 molecules. That interfered with V. cholerae progress. Two years later, the Cornell team showed that V. cholerae-infected mice treated with engineered E.coli had a 92 percent survival rate.

These findings inspired researchers to sic the good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi onto the drug-resistant ones.

Three years later in 2011, Singapore-based scientists engineered E.coli to detect and destroy Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an often drug-resistant pathogen that causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. Once the genetically engineered E.coli found its target through its quorum sensing molecules, it then released a peptide, that could eradicate 99 percent of P. aeruginosa cells in a test-tube experiment. The team outlined their work in a Molecular Systems Biology study.

“At the time, we knew that we were entering new, uncharted territory,” says lead author Matthew Chang, an associate professor and synthetic biologist at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the study. “To date, we are still in the process of trying to understand how long these microbes stay in our bodies and how they might continue to evolve.”

More teams followed the same path. In a 2013 study, MIT researchers also genetically engineered E.coli to detect P. aeruginosa via the pathogen’s quorum-sensing molecules. It then destroyed the pathogen by secreting a lab-made toxin.

Probiotics that fight

A year later in 2014, a Nature study found that the abundance of Ruminococcus obeum, a probiotic bacteria naturally occurring in the human microbiome, interrupts and reduces V.cholerae’s colonization— by detecting the pathogen’s quorum sensing molecules. The natural accumulation of R. obeum in Bangladeshi adults helped them recover from cholera despite living in an area with frequent outbreaks.

The findings from 2008 to 2014 inspired Collins and his team to delve into how good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi can attack drug-resistant bacteria. In 2018, Collins and his team developed the engineered probiotic strategy. They tweaked a bacteria commonly found in yogurt called Lactococcus lactis to treat cholera.

Engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut. --José Rubén Morones-Ramírez.

More scientists followed with more experiments. So far, researchers have engineered various probiotic organisms to fight pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (leading cause of skin, tissue, bone, joint and blood infections) and Clostridium perfringens (which causes watery diarrhea) in test-tube and animal experiments. In 2020, Russian scientists engineered a probiotic called Pichia pastoris to produce an enzyme called lysostaphin that eradicated S. aureus in vitro. Another 2020 study from China used an engineered probiotic bacteria Lactobacilli casei as a vaccine to prevent C. perfringens infection in rabbits.

In a study last year, Ramírez’s group at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, engineered E. coli to detect quorum-sensing molecules from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA, a notorious superbug. The E. coli then releases a bacteriocin that kills MRSA. “An antibiotic is just a molecule that is not intelligent,” says Ramírez. “On the other hand, engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut.”

Collins and Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, found that engineered E. coli can help treat other conditions—such as phenylketonuria, a rare metabolic disorder, that causes the build-up of an amino acid phenylalanine. Their start-up Synlogic aims to commercialize the technology, and has completed a phase 2 clinical trial.

Circumventing the challenges

The bacteria-engineering technique is not without pitfalls. One major challenge is that beneficial gut bacteria produce their own quorum-sensing molecules that can be similar to those that pathogens secrete. If an engineered bacteria’s biosensor is not specific enough, it will be ineffective.

Another concern is whether engineered bacteria might mutate after entering the gut. “As with any technology, there are risks where bad actors could have the capability to engineer a microbe to act quite nastily,” says Collins of MIT. But Collins and Ramírez both insist that the chances of the engineered bacteria mutating on its own are virtually non-existent. “It is extremely unlikely for the engineered bacteria to mutate,” Ramírez says. “Coaxing a living cell to do anything on command is immensely challenging. Usually, the greater risk is that the engineered bacteria entirely lose its functionality.”

However, the biggest challenge is bringing the curative bacteria to consumers. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in antibiotics or their alternatives because it’s less profitable than developing new medicines for non-infectious diseases. Unlike the more chronic conditions like diabetes or cancer that require long-term medications, infectious diseases are usually treated much quicker. Running clinical trials are expensive and antibiotic-alternatives aren’t lucrative enough.

“Unfortunately, new medications for antibiotic resistant infections have been pushed to the bottom of the field,” says Lu of MIT. “It's not because the technology does not work. This is more of a market issue. Because clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the only solution is that governments will need to fund them.” Lu stresses that societies must lobby to change how the modern healthcare industry works. “The whole world needs better treatments for antibiotic resistance.”