Mind the (Vote) Gap: Can We Get More STEM Students to the Polls?

An "I Voted" sticker.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

By the numbers, American college students who major in STEM disciplines—science, technology, engineering, and math—aren't big on voting. In fact, recent research suggests they're the least likely group of students to head to the ballot box, even as American political leaders cast doubt on the very kinds of expertise those students are developing on campus.

Worried educators say it's time for a rethink of STEM education at the college level. Armed with success stories and model courses, educators are pushing for colleagues to add relevance to STEM education—and instill a sense of civic duty—by bringing the outside world in.

"It's a matter of what's in the curriculum, how faculty spend their time. There are opportunities to weave [policy] within the curriculum," said Nancy L. Thomas, director of Tufts University's Institute for Democracy & Higher Education.

The most recent student voting numbers come from the 2018 mid-term election, when a national Democratic wave brought voters to the polls. Just over a third of STEM college students surveyed said they voted, the lowest percentage of six subject areas, according to a report from the institute at Tufts. Students in the education, social sciences, and humanities fields had the highest voting rates at 47%, 41%, and 39%, respectively.

Students across the board were much less engaged in the mid-year election of 2014, when just 28% of education students surveyed said they voted. STEM students again stood at the rear, with just 16% voting.

(The report analyzed whether more than 10 million college students at 1,031 U.S. institutions voted in 2014 and 2018. At the request of this magazine, the institute at Tufts removed non-U.S. resident students—who can't vote—from the findings to see if the results changed. Voting rates among STEM students remained among the lowest.)

Why aren't STEM students engaged in politics? "I have no reason to think that science students don't care about public policy issues," Tufts University's Thomas said. Instead, she believes that colleges fail to inspire STEM students to think beyond lectures and homework.

Enter the SENCER project—Science Education for New Civic Engagements and Responsibilities. Since 2001, the project has taught thousands of educators and students how to connect science and citizenship.

The roots of the project go back to 1990, when Rutgers University microbiologist Monica Devanas was assigned to teach a general-education class called "Biomedical Issues of AIDS." She decided to expand the curriculum to encompass insights about a wide range of societal issues. Guest speakers from the community, including a man with a grim diagnosis, talked about the disease and its spread. And Devanas's colleagues in a wide variety of disciplines offered course sections about AIDS and its role in areas such as literature, prisons and law.

"I always tried to make a connection, hoping to create scientifically engaged citizens by explaining the science to them in ways that they could understand."

When she first taught the class, 450 students signed up instead of the expected 100. Devanas, who'd only ever taught a few dozen students with a blackboard, suddenly had to figure out how to teach hundreds at once with the standard technology of the time: an overhead projector.

Devanas, who taught the hugely popular class for the next 18 years, said the course worked because it linked the AIDS epidemic, a hot topic at the time, to the outer world beyond immune cells and test tubes. "You really need to make it very personal and relevant. When you talk about treatment for AIDS or the cost of drugs: Who pays for this?" she said. "I always tried to make a connection, hoping to create scientifically engaged citizens by explaining the science to them in ways that they could understand."

How can other educators learn to create compelling courses? The SENCER website offers dozens of model classes for college and K–12 educators, all with the aim of making STEM classes relevant. An engineering course, for example, could expand a discussion about the nuts and bolts of automated vehicles into a conversation about whether the cars are a good idea in the first place, said Eliza J. Reilly, executive director of the National Center for Science and Civic Engagement, where SENCER is based.

SENCER, which is government-funded, holds regular conferences and has conducted research that supports the effectiveness of its programs. "This is an educational and intellectual project rather than a get-out-the-vote project. It's not intended to create activists. Instead, it's intended to help students understand that they have power as citizens," Reilly said.

What about long-term change? Will inspiring college students to engage with politics turn them into lifetime voters? Reilly said she's not aware of any research into whether STEM students continue to vote at lower levels after they graduate. That means there's no way to know if limited civic engagement in college translates to lifelong apathy. We also don't know if lower voting rates in college may help explain why few people with STEM backgrounds run for higher office.

There's another big unknown: If more people with STEM degrees vote, will they actually support fact-based policies and candidates who listen to science? The answer is not as obvious as it may appear. At Rutgers, professor Devanas pointed to the research of Yale University law/psychology professor Dan Kahan, who found that the most scientifically literate people in the U.S. also happen to be among those most polarized over climate change. In other words, a scientific mind may not necessarily translate to a pro-science vote.

Regardless of the ultimate choices that STEM students make at the ballot box, advocates will keep encouraging educators to connect science to the world beyond the classroom. As Tufts University's Thomas explained, "it just takes a lot of creativity and will."

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Coronavirus Risk Calculators: What You Need to Know

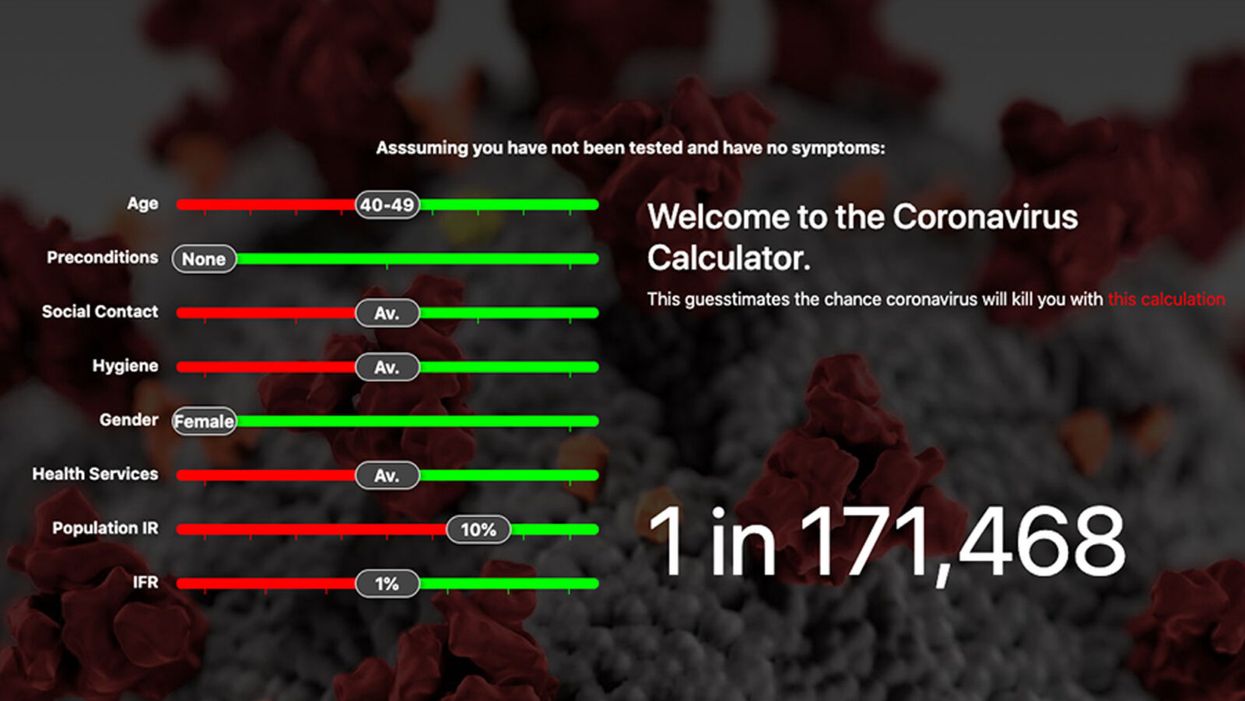

A screenshot of one coronavirus risk calculator.

People in my family seem to develop every ailment in the world, including feline distemper and Dutch elm disease, so I naturally put fingers to keyboard when I discovered that COVID-19 risk calculators now exist.

"It's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk."

But the results – based on my answers to questions -- are bewildering.

A British risk calculator developed by the Nexoid software company declared I have a 5 percent, or 1 in 20, chance of developing COVID-19 and less than 1 percent risk of dying if I get it. Um, great, I think? Meanwhile, 19 and Me, a risk calculator created by data scientists, says my risk of infection is 0.01 percent per week, or 1 in 10,000, and it gave me a risk score of 44 out of 100.

Confused? Join the club. But it's actually possible to interpret numbers like these and put them to use. Here are five tips about using coronavirus risk calculators:

1. Make Sure the Calculator Is Designed For You

Not every COVID-19 risk calculator is designed to be used by the general public. Cleveland Clinic's risk calculator, for example, is only a tool for medical professionals, not sick people or the "worried well," said Dr. Lara Jehi, Cleveland Clinic's chief research information officer.

Unfortunately, the risk calculator's web page fails to explicitly identify its target audience. But there are hints that it's not for lay people such as its references to "platelets" and "chlorides."

The 19 and Me or the Nexoid risk calculators, in contrast, are both designed for use by everyone, as is a risk calculator developed by Emory University.

2. Take a Look at the Calculator's Privacy Policy

COVID-19 risk calculators ask for a lot of personal information. The Nexoid calculator, for example, wanted to know my age, weight, drug and alcohol history, pre-existing conditions, blood type and more. It even asked me about the prescription drugs I take.

It's wise to check the privacy policy and be cautious about providing an email address or other personal information. Nexoid's policy says it provides the information it gathers to researchers but it doesn't release IP addresses, which can reveal your location in certain circumstances.

John-Arne Skolbekken, a professor and risk specialist at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, entered his own data in the Nexoid calculator after being contacted by LeapsMag for comment. He noted that the calculator, among other things, asks for information about use of recreational drugs that could be illegal in some places. "I have given away some of my personal data to a company that I can hope will not misuse them," he said. "Let's hope they are trustworthy."

The 19 and Me calculator, by contrast, doesn't gather any data from users, said Cindy Hu, data scientist at Mathematica, which created it. "As soon as the window is closed, that data is gone and not captured."

The Emory University risk calculator, meanwhile, has a long privacy policy that states "the information we collect during your assessment will not be correlated with contact information if you provide it." However, it says personal information can be shared with third parties.

3. Keep an Eye on Time Horizons

Let's say a risk calculator says you have a 1 percent risk of infection. That's fairly low if we're talking about this year as a whole, but it's quite worrisome if the risk percentage refers to today and jumps by 1 percent each day going forward. That's why it's helpful to know exactly what the numbers mean in terms of time.

Unfortunately, this information isn't always readily available. You may have to dig around for it or contact a risk calculator's developers for more information. The 19 and Me calculator's risk percentages refer to this current week based on your behavior this week, Hu said. The Nexoid calculator, by contrast, has an "infinite timeline" that assumes no vaccine is developed, said Jonathon Grantham, the company's managing director. But your results will vary over time since the calculator's developers adjust it to reflect new data.

When you use a risk calculator, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

4. Focus on the Big Picture

The Nexoid calculator gave me numbers of 5 percent (getting COVID-19) and 99.309 percent (surviving it). It even provided betting odds for gambling types: The odds are in favor of me not getting infected (19-to-1) and not dying if I get infected (144-to-1).

However, Grantham told me that these numbers "are not the whole story." Instead, he said, "it's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk." Risk bands refer to a segmentation of people into five categories, from lowest to highest risk, according to how a person's result sits relative to the whole dataset.

The Nexoid calculator says I'm in the "lowest risk band" for getting COVID-19, and a "high risk band" for dying of it if I get it. That suggests I'd better stay in the lowest-risk category because my pre-existing risk factors could spell trouble for my survival if I get infected.

Michael J. Pencina, a professor and biostatistician at Duke University School of Medicine, agreed that focusing on your general risk level is better than focusing on numbers. When you use a risk calculator, he said, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

The 19 and Me calculator, meanwhile, put my risk at 44 out of 100. Hu said that a score of 50 represents the typical person's risk of developing serious consequences from another disease – the flu.

5. Remember to Take Action

Hu, who helped develop the 19 and Me risk calculator, said it's best to use it to "understand the relative impact of different behaviors." As she noted, the calculator is designed to allow users to plug in different answers about their behavior and immediately see how their risk levels change.

This information can help us figure out if we should change the way we approach the world by, say, washing our hands more or avoiding more personal encounters.

"Estimation of risk is only one part of prevention," Pencina said. "The other is risk factors and our ability to reduce them." In other words, odds, percentages and risk bands can be revealing, but it's what we do to change them that matters.

Will the Pandemic Propel STEM Experts to Political Power?

The White House rising out of a Petri dish.

If your car won't run, you head to a mechanic. If your faucet leaks, you contact a plumber. But what do you do if your politics are broken? You call a… lawyer.

"Scientists have been more engaged with politics over the past three years amid a consistent sidelining of science and expertise, and now the pandemic has crystalized things even more."

That's been the American way since the beginning. Thousands of members of the House and Senate have been attorneys, along with nearly two dozen U.S. presidents from John Adams to Abraham Lincoln to Barack Obama. But a band of STEM professionals is changing the equation. They're hoping anger over the coronavirus pandemic will turn their expertise into a political superpower that propels more of them into office.

"This could be a turning point, part of an acceleration of something that's already happening," said Nancy Goroff, a New York chemistry professor who's running for a House seat in Long Island and will apparently be the first female scientist with a Ph.D. in Congress. "Scientists have been more engaged with politics over the past three years amid a consistent sidelining of science and expertise, and now the pandemic has crystalized things even more."

Professionals in the science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM) fields don't have an easy task, however. To succeed, they must find ways to engage with voters instead of their usual target audiences — colleagues, patients and students. And they'll need to beat back a long-standing political tradition that has made federal and state politics a domain of attorneys and businesspeople, not nurses and biologists.

In the 2017-2018 Congress, more members of Congress said they'd worked as radio talk show hosts (seven) and as car dealership owners (six) than scientists (three — a physicist, a microbiologist, and a chemist), according to a 2018 report from the Congressional Research Service. There were more bankers (18) than physicians (14), more management consultants (18) than engineers (11), and more former judges (15) than dentists (4), nurses (2), veterinarians (3), pharmacists (1) and psychologists (3) combined.

In 2018, a "STEM wave" brought nine members with STEM backgrounds into office. But those with initials like PhD, MD and RN after their names are still far outnumbered by Esq. and MBA types.

Why the gap? Astrophysicist Rush Holt Jr., who served from 1999-2015 as a House representative from New Jersey, thinks he knows. "I have this very strong belief, based on 16 years in Congress and a long, intense public life, that the problem is not with science or the scientists," said. "It has to do with the fact that the public just doesn't pay attention to science. It never occurs to them that they have any role in the matter."

But Holt, former chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, believes change is on the way. "It's likely that the pandemic will affect people's attitudes," former congressman Holt said, "and lead them to think that they need more scientific thinking in policy-making and legislating." Holt's father was a U.S. senator from West Virginia, so he grew up with a political education. But how can scientists and medical professionals succeed if they have no background in the art of wooing voters?

That's where an organization called 314 Action comes in. Named after the first three digits of pi, 314 Action declares itself to be the "pro-science resistance" and says it's trained more than 1,400 scientists to run for public office.

In 2018, 9 out of 13 House and Senate candidates endorsed by the group won their races. In 2020, 314 Action is endorsing 12 candidates for the House (including an engineer), four for the Senate (including an astronaut) and one for governor (a mathematician in Kansas). It expects to spend $10 million-$20 million to support campaigns this year.

"Physicians, scientists and engineers are problem-solvers," said Shaughnessy Naughton, a Pennsylvania chemist who founded 314 Action after an unsuccessful bid for Congress. "They're willing to dive into issues, and their skills would benefit policy decisions that extend way beyond their scientific fields of expertise."

Like many political organizations, 314 Action focuses on teaching potential candidate how to make it in politics, aiming to help them drop habits that fail to bridge the gap between scientists and civilians. "Their first impulse is not to tell a story," public speaking coach Chris Jahnke told the public radio show "Marketplace" in 2018. "They would rather start with a stat." In a training session, Jahnke aimed to teach them to do both effectively.

"It just comes down to being able to speak about general principles in regular English, and to always have the science intertwined with basic human values," said Rep. Kim Schrier, a Washington state pediatrician who won election to Congress in 2018.

She believes her experience on the job has helped her make connections with voters. In a chat with parents about vaccines for their child, for example, she knows not to directly jump into an arcane discussion of case-control studies.

The best alternative, she said, is to "talk about how hard it is to be a parent making these decisions, feeling scared and worried. Then say that you've looked at the data and the research, and point out that pediatricians would never do anything to hurt children because we want to do everything that is good for them. When you speak heart to heart, it gets across the message and the credibility of medicine and science."

The pandemic "will hopefully awaken people and trigger a change that puts science, medicine and public health on a pedestal where science is revered and not dismissed as elitist."

Communication skills will be especially important if the pandemic spurs more Americans to focus on politics and the records of incumbents in regard to matters like public health and climate change. Thousands of candidates will have to address the nation's coronavirus response, and a survey commissioned by 314 Action suggests that voters may be receptive to those with STEM backgrounds. The poll, of 1,002 likely voters in early April 2020, found that 41%-46% of those surveyed said they'd be "much more favorable" toward candidates who were doctors, nurses, scientists and public health professionals. Those numbers were the highest in the survey compared to just 9% for lawyers.

The pandemic "will hopefully awaken people and trigger a change that puts science, medicine and public health on a pedestal where science is revered and not dismissed as elitist," Dr. Schrier said. "It will come from a recognition that what's going to get us out of this bind are scientists, vaccine development and the hard work of the people in public health on the ground."

[This article was originally published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]