Inside Scoop: How a DARPA Scientist Helped Usher in a Game-Changing Covid Treatment

Amy Jenkins is a program manager for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency's Biological Technologies Office, which runs a project called the Pandemic Prevention Platform.

Amy Jenkins was in her office at DARPA, a research and development agency within the Department of Defense, when she first heard about a respiratory illness plaguing the Chinese city of Wuhan. Because she's a program manager for DARPA's Biological Technologies Office, her colleagues started stopping by. "It's really unusual, isn't it?" they would say.

At the time, China had a few dozen cases of what we now call COVID-19. "We should maybe keep an eye on that," she thought.

Early in 2020, still just keeping watch, she was visiting researchers working on DARPA's Pandemic Prevention Platform (P3), a project to develop treatments for "any known or previously unknown infectious threat," within 60 days of its appearance. "We looked at each other and said, 'Should we be doing something?'" she says.

For projects like P3, groups of scientists—often at universities and private companies—compete for DARPA contracts, and program managers like Jenkins oversee the work. Those that won the P3 bid included scientists at AbCellera Biologics, Inc., AstraZeneca, Duke University, and Vanderbilt University.

At the time Jenkins was talking to the P3 performers, though, they didn't have evidence of community transmission. "We would have to cross that bar before we considered doing anything," she says.

The world soon leapt far over that bar. By the time Jenkins and her team decided P3 should be doing something—with their real work beginning in late February--it was too late to prevent this pandemic. But she could help P3 dig into the chemical foundations of COVID-19's malfeasance, and cut off its roots. That work represents, in fact, her roots.

In late February 2020, DARPA received a single blood sample from a recovered COVID-19 patient, in which P3 researchers could go fishing for antibodies. The day it arrived, Jenkins's stomach roiled. "We get one shot," she thought.

Fighting the Smallest Enemies

Jenkins, who's in her early 40s, first got into germs the way many 90s kids did: by reading The Hot Zone, a novel about a hemorrhagic fever gone rogue. It wasn't exactly the disintegrating organs that hooked her. It was the idea that "these very pathogens that we can't even see can make us so sick and bring us to our knees," she says. Reading about scientists facing down deadly disease, she wondered, "How do these things make you so sick?"

She chased that question in college, majoring in both biomolecular science and chemistry, and later became an antibody expert. Antibodies are proteins that hook to a pathogen to block it from attaching to your cells, or tag it for destruction by the rest of the immune system. Soon, she jumped on the "monoclonal antibodies" train—developing synthetic versions of these natural defenses, which doctors can give to people to help them battle an early-stage infection, and even to prevent an infection from taking root after an exposure.

Jenkins likens the antibody treatments to the old aphorism about fishing: Vaccines teach your body how to fish, but antibodies simply give your body the pesca-fare. While that, as the saying goes, won't feed you for a lifetime, it will last a few weeks or months. Monoclonal antibodies thus are a promising preventative option in the immediate short-term when a vaccine hasn't yet been given (or hasn't had time to produce an immune response), as well as an important treatment weapon in the current fight. After former president Donald Trump contracted COVID-19, he received a monoclonal antibody treatment from biotech company Regeneron.

As for Jenkins, she started working as a DARPA Biological Technologies Office contractor soon after completing her postdoc. But it was a suit job, not a labcoat job. And suit jobs, at first, left Jenkins conflicted, worried about being bored. She'd give it a year, she thought. But the year expired, and bored she was not. Around five years later, in June 2019, the agency hired her to manage several of the office's programs. A year into that gig, the world was months into a pandemic.

The Pandemic Pivot

At DARPA, Jenkins inherited five programs, including P3. P3 works by taking blood from recovered people, fishing out their antibodies, identifying the most effective ones, and then figuring out how to manufacture them fast. Back then, P3 existed to help with nebulous, future outbreaks: Pandemic X. Not this pandemic. "I did not have a crystal ball," she says, "but I will say that all of us in the infectious diseases and public-health realm knew that the next pandemic was coming."

Three days after a January 2020 meeting with P3 researchers, COVID-19 appeared in Seattle, then began whipping through communities. The time had come for P3 teams to swivel. "We had done this," she says. "We had practiced this before." But would their methods stand up to something unknown, racing through the global population? "The big anxiety was, 'Wow, this was real,'" says Jenkins.

While facing down that realness, Jenkins was also managing other projects. In one called PREPARE, groups develop "medical countermeasures" that modulate a person's genetic code to boost their bodies' responses to threats. Another project, NOW, envisions shipping-container-sized factories that can make thousands of vaccine doses in days. And then there's Prometheus—which means "forethought" in Greek, and is the name of the god who stole fire and gave it to humans. Wrapping up as COVID ramped up, Prometheus aimed to identify people who are contagious—with whatever—before they start coughing, and even if they never do.

All of DARPA's projects focus on developing early-stage technology, passing it off to other agencies or industry to put it into operation. The orientation toward a specific goal appealed to Jenkins, as a contrast to academia. "You go down a rabbit hole for years at a time sometimes, chasing some concept you found interesting in the lab," she says. That's good for the human pursuit of knowledge, and leads to later applications, but DARPA wants a practical prototype—stat.

"Dual-Use" Technologies

That desire, though, and the fact that DARPA is a defense agency, present philosophical complications. "Bioethics in the national-security context turns all the dials up to 10+," says Jonathan Moreno, a medical ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania.

While developing antibody treatments to stem a pandemic seems straightforwardly good, all biological research—especially that backed by military money—requires evaluating potential knock-on applications, even those that might come from outside the entity that did the developing. As Moreno put it, "Albert Einstein wasn't thinking about blowing up Hiroshima." Particularly sensitive are so-called "dual-use" technologies—those tools that could be used for both benign and nefarious purposes, or are of interest to both the civilian and military worlds.

Moreno takes Prometheus itself as an example of "dual-use" technology. "Think about somebody wearing a suicide vest. Instead of a suicide vest, make them extremely contagious with something. The flu plus Ebola," he says. "Send them someplace, a sensitive environment. We would like to be able to defend against that"—not just tell whether Uncle Fred is bringing asymptomatic COVID home for Christmas. Prometheus, Jenkins says, had safety in mind from the get-go, and required contenders to "develop a risk mitigation plan" and "detail their strategy for appropriate control of information."

To look at a different program, if you can modulate genes to help healing, you probably know something (or know someone else could infer something) about how to hinder healing. Those sorts of risks are why PREPARE researchers got their own "ethical, legal, and social implications" panel, which meets quarterly "to ensure that we are performing all research and publications in a safe and ethical manner," says Jenkins.

DARPA as a whole, Moreno says, is institutionally sensitive to bioethics. The agency has ethics panels, and funded a 2014 National Academies assessment of how to address the "ethical, legal, and societal issues" around technology that has military relevance. "In the cases of biotechnologies where some of that research brushes up against what could legitimately be considered dual-use, that in itself justifies our investment," says Jenkins. "DARPA deliberately focuses on safety and countermeasures against potentially dangerous technologies, and we structure our programs to be transparent, safe, and legal."

Going Fishing

In late February 2020, DARPA received a single blood sample from a recovered COVID-19 patient, in which P3 researchers could go fishing for antibodies. The day it arrived, Jenkins's stomach roiled. "We get one shot," she thought.

As scientists from the P3-funded AbCellera went through the processes they'd practiced, Jenkins managed their work, tracking progress and relaying results. Soon, the team had isolated a suitable protein: bamlanivimab. It attaches to and blocks off the infamous spike proteins on SARS-CoV-2—those sticky suction-cups in illustrations. Partnering with Eli Lilly in a manufacturing agreement, the biotech company brought it to clinical trials in May, just a few months after its work on the deadly pathogen began, after much of the planet became a hot zone.

On November 10—Jenkins's favorite day at the (home) office—the FDA provided Eli Lilly emergency use authorization for bamlanivimab. But she's only mutedly screaming (with joy) inside her heart. "This pandemic isn't 'one morning we're going to wake up and it's all over,'" she says. When it is over, she and her colleagues plan to celebrate their promethean work. "I'm hoping to be able to do it in person," she says. "Until then, I have not taken a breath."

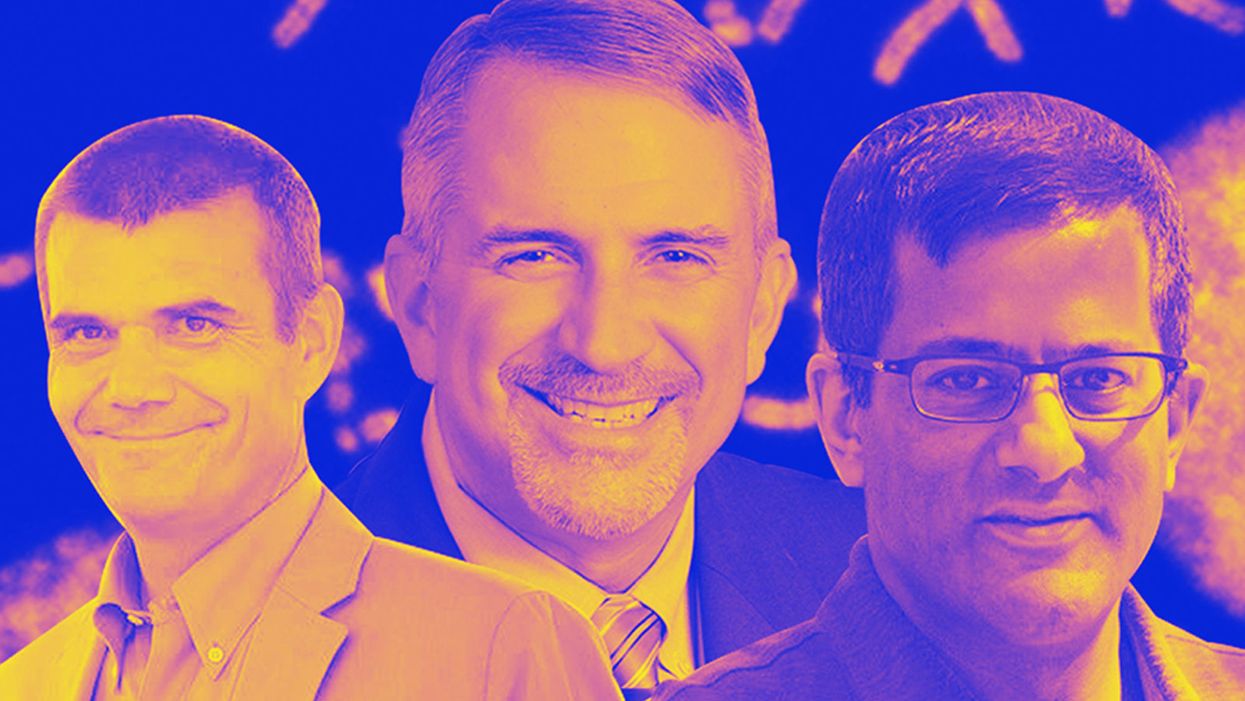

Meet the Scientists on the Frontlines of Protecting Humanity from a Man-Made Pathogen

From left: Jean Peccoud, Randall Murch, and Neeraj Rao.

Jean Peccoud wasn't expecting an email from the FBI. He definitely wasn't expecting the agency to invite him to a meeting. "My reaction was, 'What did I do wrong to be on the FBI watch list?'" he recalls.

You use those blueprints for white-hat research—which is, indeed, why the open blueprints exist—or you can do the same for a black-hat attack.

He didn't know what the feds could possibly want from him. "I was mostly scared at this point," he says. "I was deeply disturbed by the whole thing."

But he decided to go anyway, and when he traveled to San Francisco for the 2008 gathering, the reason for the e-vite became clear: The FBI was reaching out to researchers like him—scientists interested in synthetic biology—in anticipation of the potential nefarious uses of this technology. "The whole purpose of the meeting was, 'Let's start talking to each other before we actually need to talk to each other,'" says Peccoud, now a professor of chemical and biological engineering at Colorado State University. "'And let's make sure next time you get an email from the FBI, you don't freak out."

Synthetic biology—which Peccoud defines as "the application of engineering methods to biological systems"—holds great power, and with that (as always) comes great responsibility. When you can synthesize genetic material in a lab, you can create new ways of diagnosing and treating people, and even new food ingredients. But you can also "print" the genetic sequence of a virus or virulent bacterium.

And while it's not easy, it's also not as hard as it could be, in part because dangerous sequences have publicly available blueprints. You use those blueprints for white-hat research—which is, indeed, why the open blueprints exist—or you can do the same for a black-hat attack. You could synthesize a dangerous pathogen's code on purpose, or you could unwittingly do so because someone tampered with your digital instructions. Ordering synthetic genes for viral sequences, says Peccoud, would likely be more difficult today than it was a decade ago.

"There is more awareness of the industry, and they are taking this more seriously," he says. "There is no specific regulation, though."

Trying to lock down the interconnected machines that enable synthetic biology, secure its lab processes, and keep dangerous pathogens out of the hands of bad actors is part of a relatively new field: cyberbiosecurity, whose name Peccoud and colleagues introduced in a 2018 paper.

Biological threats feel especially acute right now, during the ongoing pandemic. COVID-19 is a natural pathogen -- not one engineered in a lab. But future outbreaks could start from a bug nature didn't build, if the wrong people get ahold of the right genetic sequences, and put them in the right sequence. Securing the equipment and processes that make synthetic biology possible -- so that doesn't happen -- is part of why the field of cyberbiosecurity was born.

The Origin Story

It is perhaps no coincidence that the FBI pinged Peccoud when it did: soon after a journalist ordered a sequence of smallpox DNA and wrote, for The Guardian, about how easy it was. "That was not good press for anybody," says Peccoud. Previously, in 2002, the Pentagon had funded SUNY Stonybrook researchers to try something similar: They ordered bits of polio DNA piecemeal and, over the course of three years, strung them together.

Although many years have passed since those early gotchas, the current patchwork of regulations still wouldn't necessarily prevent someone from pulling similar tricks now, and the technological systems that synthetic biology runs on are more intertwined — and so perhaps more hackable — than ever. Researchers like Peccoud are working to bring awareness to those potential problems, to promote accountability, and to provide early-detection tools that would catch the whiff of a rotten act before it became one.

Peccoud notes that if someone wants to get access to a specific pathogen, it is probably easier to collect it from the environment or take it from a biodefense lab than to whip it up synthetically. "However, people could use genetic databases to design a system that combines different genes in a way that would make them dangerous together without each of the components being dangerous on its own," he says. "This would be much more difficult to detect."

After his meeting with the FBI, Peccoud grew more interested in these sorts of security questions. So he was paying attention when, in 2010, the Department of Health and Human Services — now helping manage the response to COVID-19 — created guidance for how to screen synthetic biology orders, to make sure suppliers didn't accidentally send bad actors the sequences that make up bad genomes.

Guidance is nice, Peccoud thought, but it's just words. He wanted to turn those words into action: into a computer program. "I didn't know if it was something you can run on a desktop or if you need a supercomputer to run it," he says. So, one summer, he tasked a team of student researchers with poring over the sentences and turning them into scripts. "I let the FBI know," he says, having both learned his lesson and wanting to get in on the game.

Peccoud later joined forces with Randall Murch, a former FBI agent and current Virginia Tech professor, and a team of colleagues from both Virginia Tech and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, on a prototype project for the Department of Defense. They went into a lab at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln and assessed all its cyberbio-vulnerabilities. The lab develops and produces prototype vaccines, therapeutics, and prophylactic components — exactly the kind of place that you always, and especially right now, want to keep secure.

"We were creating wiki of all these nasty things."

The team found dozens of Achilles' heels, and put them in a private report. Not long after that project, the two and their colleagues wrote the paper that first used the term "cyberbiosecurity." A second paper, led by Murch, came out five months later and provided a proposed definition and more comprehensive perspective on cyberbiosecurity. But although it's now a buzzword, it's the definition, not the jargon, that matters. "Frankly, I don't really care if they call it cyberbiosecurity," says Murch. Call it what you want: Just pay attention to its tenets.

A Database of Scary Sequences

Peccoud and Murch, of course, aren't the only ones working to screen sequences and secure devices. At the nonprofit Battelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio, for instance, scientists are working on solutions that balance the openness inherent to science and the closure that can stop bad stuff. "There's a challenge there that you want to enable research but you want to make sure that what people are ordering is safe," says the organization's Neeraj Rao.

Rao can't talk about the work Battelle does for the spy agency IARPA, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, on a project called Fun GCAT, which aims to use computational tools to deep-screen gene-sequence orders to see if they pose a threat. It can, though, talk about a twin-type internal project: ThreatSEQ (pronounced, of course, "threat seek").

The project started when "a government customer" (as usual, no one will say which) asked Battelle to curate a list of dangerous toxins and pathogens, and their genetic sequences. The researchers even started tagging sequences according to their function — like whether a particular sequence is involved in a germ's virulence or toxicity. That helps if someone is trying to use synthetic biology not to gin up a yawn-inducing old bug but to engineer a totally new one. "How do you essentially predict what the function of a novel sequence is?" says Rao. You look at what other, similar bits of code do.

"We were creating wiki of all these nasty things," says Rao. As they were working, they realized that DNA manufacturers could potentially scan in sequences that people ordered, run them against the database, and see if anything scary matched up. Kind of like that plagiarism software your college professors used.

Battelle began offering their screening capability, as ThreatSEQ. When customers -- like, currently, Twist Bioscience -- throw their sequences in, and get a report back, the manufacturers make the final decision about whether to fulfill a flagged order — whether, in the analogy, to give an F for plagiarism. After all, legitimate researchers do legitimately need to have DNA from legitimately bad organisms.

"Maybe it's the CDC," says Rao. "If things check out, oftentimes [the manufacturers] will fulfill the order." If it's your aggrieved uncle seeking the virulent pathogen, maybe not. But ultimately, no one is stopping the manufacturers from doing so.

Beyond that kind of tampering, though, cyberbiosecurity also includes keeping a lockdown on the machines that make the genetic sequences. "Somebody now doesn't need physical access to infrastructure to tamper with it," says Rao. So it needs the same cyber protections as other internet-connected devices.

Scientists are also now using DNA to store data — encoding information in its bases, rather than into a hard drive. To download the data, you sequence the DNA and read it back into a computer. But if you think like a bad guy, you'd realize that a bad guy could then, for instance, insert a computer virus into the genetic code, and when the researcher went to nab her data, her desktop would crash or infect the others on the network.

Something like that actually happened in 2017 at the USENIX security symposium, an annual programming conference: Researchers from the University of Washington encoded malware into DNA, and when the gene sequencer assembled the DNA, it corrupted the sequencer's software, then the computer that controlled it.

"This vulnerability could be just the opening an adversary needs to compromise an organization's systems," Inspirion Biosciences' J. Craig Reed and Nicolas Dunaway wrote in a paper for Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, included in an e-book that Murch edited called Mapping the Cyberbiosecurity Enterprise.

Where We Go From Here

So what to do about all this? That's hard to say, in part because we don't know how big a current problem any of it poses. As noted in Mapping the Cyberbiosecurity Enterprise, "Information about private sector infrastructure vulnerabilities or data breaches is protected from public release by the Protected Critical Infrastructure Information (PCII) Program," if the privateers share the information with the government. "Government sector vulnerabilities or data breaches," meanwhile, "are rarely shared with the public."

"What I think is encouraging right now is the fact that we're even having this discussion."

The regulations that could rein in problems aren't as robust as many would like them to be, and much good behavior is technically voluntary — although guidelines and best practices do exist from organizations like the International Gene Synthesis Consortium and the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Rao thinks it would be smart if grant-giving agencies like the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation required any scientists who took their money to work with manufacturing companies that screen sequences. But he also still thinks we're on our way to being ahead of the curve, in terms of preventing print-your-own bioproblems: "What I think is encouraging right now is the fact that we're even having this discussion," says Rao.

Peccoud, for his part, has worked to keep such conversations going, including by doing training for the FBI and planning a workshop for students in which they imagine and work to guard against the malicious use of their research. But actually, Peccoud believes that human error, flawed lab processes, and mislabeled samples might be bigger threats than the outside ones. "Way too often, I think that people think of security as, 'Oh, there is a bad guy going after me,' and the main thing you should be worried about is yourself and errors," he says.

Murch thinks we're only at the beginning of understanding where our weak points are, and how many times they've been bruised. Decreasing those contusions, though, won't just take more secure systems. "The answer won't be technical only," he says. It'll be social, political, policy-related, and economic — a cultural revolution all its own.

Scientists Are Building an “AccuWeather” for Germs to Predict Your Risk of Getting the Flu

A future app may help you avoid getting the flu by informing you of your local risk on a given day.

Applied mathematician Sara del Valle works at the U.S.'s foremost nuclear weapons lab: Los Alamos. Once colloquially called Atomic City, it's a hidden place 45 minutes into the mountains northwest of Santa Fe. Here, engineers developed the first atomic bomb.

Like AccuWeather, an app for disease prediction could help people alter their behavior to live better lives.

Today, Los Alamos still a small science town, though no longer a secret, nor in the business of building new bombs. Instead, it's tasked with, among other things, keeping the stockpile of nuclear weapons safe and stable: not exploding when they're not supposed to (yes, please) and exploding if someone presses that red button (please, no).

Del Valle, though, doesn't work on any of that. Los Alamos is also interested in other kinds of booms—like the explosion of a contagious disease that could take down a city. Predicting (and, ideally, preventing) such epidemics is del Valle's passion. She hopes to develop an app that's like AccuWeather for germs: It would tell you your chance of getting the flu, or dengue or Zika, in your city on a given day. And like AccuWeather, it could help people alter their behavior to live better lives, whether that means staying home on a snowy morning or washing their hands on a sickness-heavy commute.

Sara del Valle of Los Alamos is working to predict and prevent epidemics using data and machine learning.

Since the beginning of del Valle's career, she's been driven by one thing: using data and predictions to help people behave practically around pathogens. As a kid, she'd always been good at math, but when she found out she could use it to capture the tentacular spread of disease, and not just manipulate abstractions, she was hooked.

When she made her way to Los Alamos, she started looking at what people were doing during outbreaks. Using social media like Twitter, Google search data, and Wikipedia, the team started to sift for trends. Were people talking about hygiene, like hand-washing? Or about being sick? Were they Googling information about mosquitoes? Searching Wikipedia for symptoms? And how did those things correlate with the spread of disease?

It was a new, faster way to think about how pathogens propagate in the real world. Usually, there's a 10- to 14-day lag in the U.S. between when doctors tap numbers into spreadsheets and when that information becomes public. By then, the world has moved on, and so has the disease—to other villages, other victims.

"We found there was a correlation between actual flu incidents in a community and the number of searches online and the number of tweets online," says del Valle. That was when she first let herself dream about a real-time forecast, not a 10-days-later backcast. Del Valle's group—computer scientists, mathematicians, statisticians, economists, public health professionals, epidemiologists, satellite analysis experts—has continued to work on the problem ever since their first Twitter parsing, in 2011.

They've had their share of outbreaks to track. Looking back at the 2009 swine flu pandemic, they saw people buying face masks and paying attention to the cleanliness of their hands. "People were talking about whether or not they needed to cancel their vacation," she says, and also whether pork products—which have nothing to do with swine flu—were safe to buy.

At the latest meeting with all the prediction groups, del Valle's flu models took first and second place.

They watched internet conversations during the measles outbreak in California. "There's a lot of online discussion about anti-vax sentiment, and people trying to convince people to vaccinate children and vice versa," she says.

Today, they work on predicting the spread of Zika, Chikungunya, and dengue fever, as well as the plain old flu. And according to the CDC, that latter effort is going well.

Since 2015, the CDC has run the Epidemic Prediction Initiative, a competition in which teams like de Valle's submit weekly predictions of how raging the flu will be in particular locations, along with other ailments occasionally. Michael Johannson is co-founder and leader of the program, which began with the Dengue Forecasting Project. Its goal, he says, was to predict when dengue cases would blow up, when previously an area just had a low-level baseline of sick people. "You'll get this massive epidemic where all of a sudden, instead of 3,000 to 4,000 cases, you have 20,000 cases," he says. "They kind of come out of nowhere."

But the "kind of" is key: The outbreaks surely come out of somewhere and, if scientists applied research and data the right way, they could forecast the upswing and perhaps dodge a bomb before it hit big-time. Questions about how big, when, and where are also key to the flu.

A big part of these projects is the CDC giving the right researchers access to the right information, and the structure to both forecast useful public-health outcomes and to compare how well the models are doing. The extra information has been great for the Los Alamos effort. "We don't have to call departments and beg for data," says del Valle.

When data isn't available, "proxies"—things like symptom searches, tweets about empty offices, satellite images showing a green, wet, mosquito-friendly landscape—are helpful: You don't have to rely on anyone's health department.

At the latest meeting with all the prediction groups, del Valle's flu models took first and second place. But del Valle wants more than weekly numbers on a government website; she wants that weather-app-inspired fortune-teller, incorporating the many diseases you could get today, standing right where you are. "That's our dream," she says.

This plot shows the the correlations between the online data stream, from Wikipedia, and various infectious diseases in different countries. The results of del Valle's predictive models are shown in brown, while the actual number of cases or illness rates are shown in blue.

(Courtesy del Valle)

The goal isn't to turn you into a germophobic agoraphobe. It's to make you more aware when you do go out. "If you know it's going to rain today, you're more likely to bring an umbrella," del Valle says. "When you go on vacation, you always look at the weather and make sure you bring the appropriate clothing. If you do the same thing for diseases, you think, 'There's Zika spreading in Sao Paulo, so maybe I should bring even more mosquito repellent and bring more long sleeves and pants.'"

They're not there yet (don't hold your breath, but do stop touching your mouth). She estimates it's at least a decade away, but advances in machine learning could accelerate that hypothetical timeline. "We're doing baby steps," says del Valle, starting with the flu in the U.S., dengue in Brazil, and other efforts in Colombia, Ecuador, and Canada. "Going from there to forecasting all diseases around the globe is a long way," she says.

But even AccuWeather started small: One man began predicting weather for a utility company, then helping ski resorts optimize their snowmaking. His influence snowballed, and now private forecasting apps, including AccuWeather's, populate phones across the planet. The company's progression hasn't been without controversy—privacy incursions, inaccuracy of long-term forecasts, fights with the government—but it has continued, for better and for worse.

Disease apps, perhaps spun out of a small, unlikely team at a nuclear-weapons lab, could grow and breed in a similar way. And both the controversies and public-health benefits that may someday spin out of them lie in the future, impossible to predict with certainty.