Sustainable Urban Farming Has a Rising Hot Star: Bugs

The larvae of adult black soldier flies can turn food waste into sustainable protein with minimal methane gas emissions.

In Sydney, Australia, in the basement of an inner-city high-rise, lives a mass of unexpected inhabitants: millions of maggots. The insects are far from unwelcome. They are there to feast on the food waste generated by the building's human residents.

Goterra, the start-up that installed the maggots in the building in December, belongs to the rapidly expanding insect agriculture industry, which is experiencing a surge of investment worldwide.

The maggots – the larvae of the black soldier fly – are voracious, unfussy eaters. As adult flies, they don't eat, so the young fatten up swiftly on whatever they can get. Goterra's basement colony can munch through 5 metric tons of waste in a day.

"Maggots are nature's cleaners," says Bob Gordon, Head of Growth at Goterra. "They're a great tool to manage waste streams."

Their capacity to consume presents a neat response to the problem of food waste, which contributes up to 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions each year as it rots in landfill.

"The maggots eat the food fairly fresh," Gordon says. "So, there's minimal degradation and you don't get those methane emissions."

Alongside their ability to devour waste, the soldier fly larvae hold further agricultural promise: they yield an incredibly efficient protein. After the maggots have binged for about 12 days, Goterra harvests and processes them into a protein-rich livestock feed. Their excrement, known as frass, is also collected and turned into soil conditioner.

"We are producing protein in a basement," says Gordon. "It's urban farming – really sustainable, urban farming."

Goterra's module in the basement at Barangaroo, Sydney.

Supplied by Goterra

Goterra's founder Olympia Yarger started producing the insects in "buckets in her backyard" in 2016. Today, Goterra has a large-scale processing plant and has developed proprietary modules – in shipping containers – that use robotics to manage the larvae.

The modules have been installed on site at municipal buildings, hospitals, supermarkets, several McDonald's restaurants, and a range of smaller enterprises in Australia. Users pay a subscription fee and simply pour in the waste; Goterra visits once a fortnight to harvest the bugs.

Insect agriculture is well established outside of the West, and the practice is gaining traction around the world. China has mega-facilities that can process hundreds of tons of waste in a day. In Kenya, a program recently trained 2000 farmers in soldier fly farming to boost their economic security. French biotech company InnovaFeed, in partnership with US agricultural heavyweight ADM, plans to build "the world's largest insect protein facility" in Illinois this year.

"The [maggots] are science fiction on earth. Watching them work is awe-inspiring."

But the concept is still not to everyone's taste.

"This is still a topic that I say is a bit like black liquorice – people tend to either really like it or really don't," says Wendy Lu McGill, Communications Director at the North American Coalition of Insect Agriculture (NACIA).

Formed in 2016, NACIA now has over 100 members – including researchers and commercial producers of black soldier flies, meal worms and crickets.

McGill says there have been a few iterations of insect agriculture in the US – beginning with worms produced for bait after World War II then shifting to food for exotic pets. The current focus – "insects as food and feed" – took root about a decade ago, with the establishment of the first commercial farms for this purpose.

"We're starting to see more expansion in the U.S. and a lot of the larger investments have been for black soldier fly producers," McGill says. "They tend to have larger facilities and the animal feed market they're looking at is potentially quite large."

InnovaFeed's Illinois facility is set to produce 60,000 metric tons of animal feed protein per year.

"They'll be trying to employ many different circular principles," McGill says of the project. "For example, the heat from the feed factory – the excess heat that would normally just be vented – will be used to heat the other side that's raising the black soldier fly."

Although commercial applications have started to flourish recently, scientific knowledge of the black soldier fly's potential has existed for decades.

Dr. Jeffery Tomberlin, an entomologist at Texas A&M University, has been studying the insect for over 20 years, contributing to key technologies used in the industry. He also founded Evo, a black soldier fly company in Texas, which feeds its larvae the waste from a local bakery and distillery.

"They are science fiction on earth," he says of the maggots. "Watching them work is awe-inspiring."

Tomberlin says fly farms can work effectively at different scales, and present possibilities for non-Western countries to shift towards "commodity independence."

"You don't have to have millions of dollars invested to be successful in producing this insect," he says. "[A farm] can be as simple as an open barn along the equator to a 30,000 square-foot indoor facility in the Netherlands."

As the world's population balloons, food insecurity is an increasing concern. By 2050, the UN predicts that to feed our projected population we will need to ramp up food production by at least 60%. Insect agriculture, which uses very little land and water compared to traditional livestock farming, could play a key role.

Insects may become more common human food, but the current commercial focus is animal feed. Aquaculture is a key market, with insects presenting an alternative to fish meal derived from over-exploited stocks. Insect meal is also increasingly popular in pet food, particularly in Europe.

While recent investment has been strong – NACIA says 2020 was the best year yet – reaching a scale that can match existing agricultural industries and providing a competitive price point are still hurdles for insect agriculture.

But COVID-19 has strengthened the argument for new agricultural approaches, such as the decentralized, indoor systems and circular principles employed by insect farms.

"This has given the world a preview – which no one wanted – of [future] supply chain disruptions," says McGill.

As the industry works to meet demand, Tomberlin predicts diversification and product innovation: "I think food science is going to play a big part in that. They can take an insect and create ice cream." (Dried soldier fly larvae "taste kind of like popcorn," if you were wondering.)

Tomberlin says the insects could even become an interplanetary protein source: "I do believe in that. I mean, if we're going to colonize other planets, we need to be sustainable."

But he issues a word of caution about the industry growing too big, too fast: "I think we as an industry need to be very careful of how we harness and apply [our knowledge]. The black soldier fly is considered the crown jewel today, but if it's mismanaged, it can be relegated back to a past."

Goterra's Gordon also warns against rushing into mass production: "If you're just replacing big intensive animal agriculture with big intensive animal agriculture with more efficient animals, then what's the change you're really effecting?"

But he expects the industry will continue its rise though the next decade, and Goterra – fuelled by recent $8 million Series A funding – plans to expand internationally this year.

"Within 10 years' time, I would like to see the vast majority of our unavoidable food waste being used to produce maggots to go into a protein application," Gordon says.

"There's no lack of demand. And there's no lack of food waste."

Why we need to get serious about ending aging

With the population of older people projected to grow dramatically, and the cost of healthcare with it, the future welfare of the country may depend on solving aging, writes philosopher Ingemar Patrick Linden.

It is widely acknowledged that even a small advance in anti-aging science could yield benefits in terms of healthy years that the traditional paradigm of targeting specific diseases is not likely to produce. A more youthful population would also be less vulnerable to epidemics. Approximately 93 percent of all COVID-19 deaths reported in the U.S. occurred among those aged 50 or older. The potential economic benefits would be tremendous. A more youthful population would consume less medical resources and be able to work longer. A recent study published in Nature estimates that a slowdown in aging that increases life expectancy by one year would save $38 trillion per year for the U.S. alone.

A societal effort to understand, slow down, arrest or even reverse aging of at least the size of our response to COVID-19 would therefore be a rational commitment. In fact, given that America’s older population is projected to grow dramatically, and the cost of healthcare with it, it is not an overstatement to say that the future welfare of the country may depend on solving aging.

This year, the kingdom of Saudi Arabia has announced that it will spend up to 1 billion dollars per year on science with the potential to slow down the aging process. We have also seen important investments from billionaires like Google co-founder Larry Page, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, business magnate Larry Ellison, and PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel.

The U.S. government, however, is lagging: The National Institutes of Health spent less than one percent of its $43 billion budget for the fiscal year of 2021 on the National Institute on Aging’s Division of Aging Biology. When you visit the division’s webpage you find that their mission statement carefully omits any mention of the possibility of slowing down the aging process.

There is a lack of political will and leadership on the issue, and the idea that we should seek to do something about aging is generally met with a great deal of suspicion and trepidation. In a large representative study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2013, only 38% of the respondents said that they would want a treatment that could slow the aging process and allow them to live at least 120 years. Apparently, most people prefer, or at least do not mind, to age and die within a natural lifespan. This result has been confirmed by smaller studies and it is, I think, surprising. Are we not supposed to live in a youth-culture? Are people not supposed to want to stay young and alive forever? Is self-preservation not the strong drive we have always assumed it to be?

We are inundated and saturated with an ideology of death-acceptance.

In my book, The Case against Death, I suggest that we have been culturally conditioned to think that it is virtuous to accept aging and death. We are taught to believe that although aging and death seem gruesome, they are what is best for us, all things considered. This is what we are supposed to think, and the majority accept it. I call this the Wise View because death acceptance has been the dominant view of philosophers since the beginning. Socrates compared our earthly life to an illness and a prison and described death as a healer and a liberator. The Buddha taught that life is suffering and that the way to escape suffering is to end the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Stoic philosophers from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius believed that everything that happens in accordance with nature is good, and that therefore we should not only accept death but welcome it as an aspect of a perfect totality.

Epicureans agreed with these rival schools and famously argued that death cannot harm us because where we are, death is not, and where death is we are not. We cannot be harmed if we are not, so death is harmless. The simple view that death actually can harm us greatly is one of the least philosophical views one can hold.

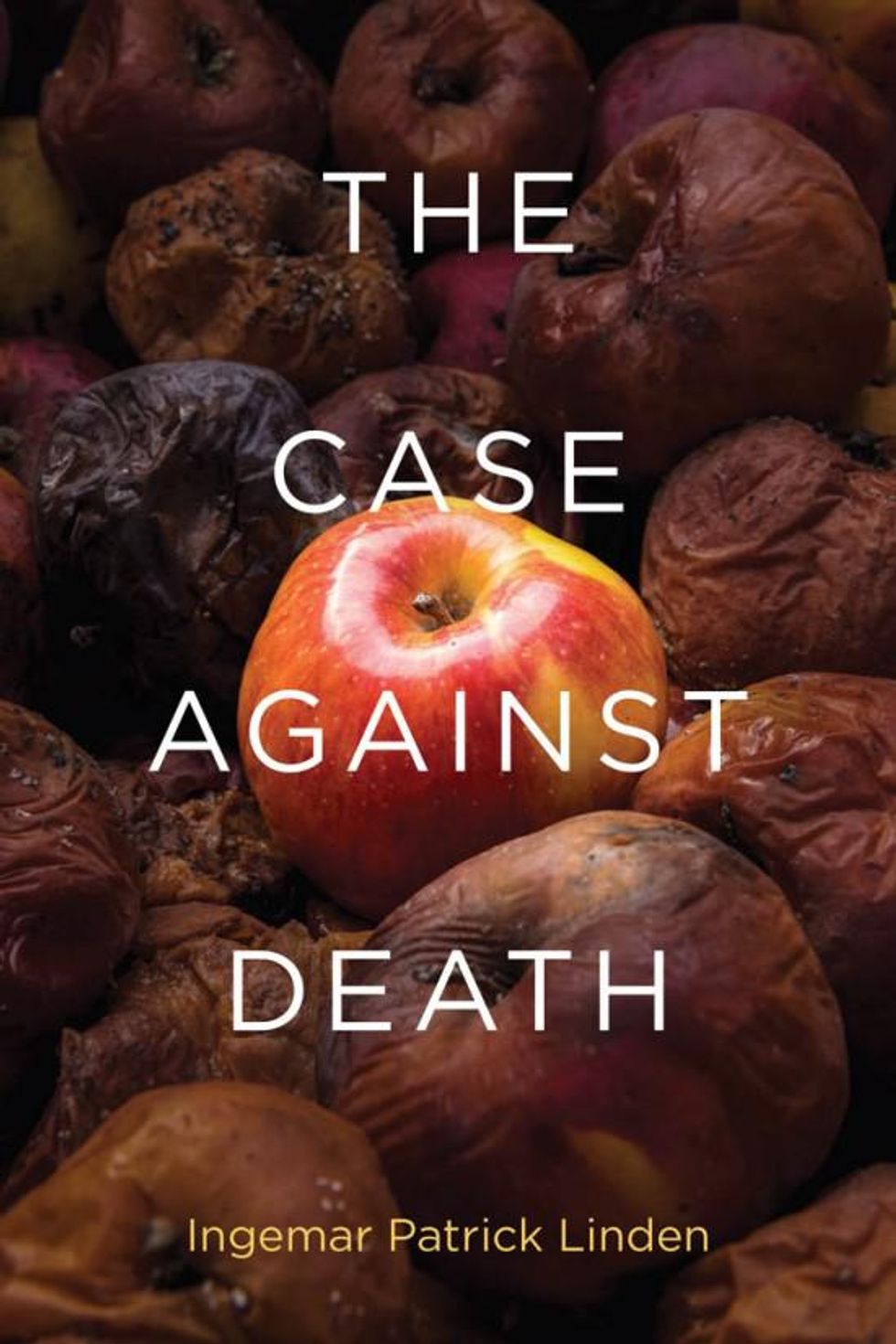

In The Case Against Death, philosopher Ingemar Patrick Linden argues that we frown on using science to prolong healthy life only because we're culturally conditioned to think that way.

Many of the stories we tell promote the Wise View. One of the earliest known pieces of literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh, follows Gilgamesh on a quest for eternal life ending with the wisdom that death is the destiny of man. Today we learn about the tedium of immortality from the children’s book Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt, and we are warned about the vice of wanting to resist death in other books and films such as J.K Rowling’s Harry Potter, where Voldemort must kill Harry as a step towards his own immortality; C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia where the White Witch has gained immortal youth and madness in equal measures; J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy where the ring extends the wearer’s life but can also destroy them, as exemplified by the creep Gollum; and Doctor Strange where life extension is the one magical power that is taboo. In Star Wars, Yoda, a stereotype of the sage, teaches us the wisdom handed down by philosophers and prophets: “Death is a natural part of life. Rejoice for those around you who transform into the Force. Mourn them do not. Miss them do not.”

We are inundated and saturated with an ideology of death-acceptance. Can the dear reader name one single story where the hero is pursuing anti-aging, longevity or immortality and the villain tries to stop her?

The Wise View resonates with us partly because we think that there is nothing we can do about aging and death, so we do not want to wish for what we cannot have. Youth and immortality are sour grapes to us. Believing that death is, all things considered, not such a bad thing, protects us from experiencing our aging and approaching death as a gruesome tragedy. This need to escape the thought that we are heading towards a personal catastrophe explains why many are so quick to accept arguments against radical life extension, despite their often glaring weaknesses.

One of the most common objections to radical life extension is that aging and death are natural. The problem with this argument is that many things that are natural are very bad, such as cancer, and other things that are not natural are very good, such as a cure for cancer. Why are we so sure that cancer is bad? Because we assume that it is bad to die. Indeed, nothing is more natural than wanting to live. We seem to need philosophers and story tellers to talk us out of it and, in the words of a distinguished bioethicist, “instruct and somewhat moderate our lust for life.”

Another standard objection is that we need a deadline, and that without death we could postpone every action forever. “Death brings urgency and seriousness to life,” say proponents of this view, but there are several problems with this argument. Even if our lives were endless, there would still be many things we would have to do at a certain time, and that could not be redone, for example, saving our planet from being destroyed, or becoming the first person on Venus. And if we prefer pleasant endless lives over unpleasant endless ones, we will have to exercise, eat right, keep our word, develop our talents, show up for time at work, pay our taxes by the due date, remember birthdays, and so on.

The Wise View provides us with a feel-good bromide for the anxiety created by the foreknowledge of our decay and death by telling us that these are not evils, but blessings in disguise. Once perhaps an innocuous delusion, today the view stands in the way of a necessary societal commitment to research that can prolong our healthy life.

Besides, even if we succeeded in ending aging, we would still die from other causes. Given the rate of accidental deaths we would be fortunate to live to age 2000 all things equal. So even if, contrary to what I have argued, we do need a deadline, we can still argue that the natural lifespan that we now labor under is inhuman and that it forces each human to limit her ambitions and to become only a fragment of all that she that could have been. Our tight time constraint imposes tragic choices and inflated opportunity costs. Death does not make life matter; it makes time matter.

The perhaps most awful argument against radical life extension is grounded in a pessimism that holds life in such little regard that it says that best of all is never to have born. This view was expressed by Ecclesiastes in the Hebrew Bible, by Sophocles and several other ancient Greeks, by the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, and recently by, among others, the South African philosopher David Benatar who argues that it is wrong to bring children into the world and that we should euthanize all sentient life. Pessimism, one suspects, largely appeals to some for reasons having to do with personal temperament, but insofar as it is built on factual beliefs, they can be addressed by providing a less negatively biased understanding of the world, by pointing out that curing aging would decrease the badness that they are so hypersensitive to, and by reminding them that if life really becomes unbearable, they are free to quit at any time. Other means of persuasion could include recommending sleep, exercise and taking long brisk walks in nature.

The Wise View provides us with a feel-good bromide for the anxiety created by the foreknowledge of our decay and death by telling us that these are not evils, but blessings in disguise. Once perhaps an innocuous delusion, today the view stands in the way of a necessary societal commitment to research that can prolong our healthy life. We need abandon it and openly admit that aging is a scourge that deserves to be fought with the combined energies equaling those expended on fighting COVID-19, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, stroke and all the other illnesses for which aging is the greatest risk factor. The fight to end aging transcends ordinary political boundaries and is therefore the kind of grand unifying enterprise that could re-energize a society suffering from divisiveness and the sense of a lack of a common purpose. It is hard to imagine a more worthwhile cause.

Could a tiny fern change the world — again?

A worker tends to a rural farm in Hanoi, Vietnam, where technology is making it easier to harvest an ancient fern called Azolla. Some scientists and farmers view Azolla as a solution to our modern-day agricultural and environmental challenges.

More than 50 million years ago, the Arctic Ocean was the opposite of a frigid wasteland. It was a gigantic lake surrounded by lush greenery brimming with flora and fauna, thanks to the humidity and warm temperatures. Giant tortoises, alligators, rhinoceros-like animals, primates, and tapirs roamed through nearby forests in the Arctic.

This greenhouse utopia abruptly changed in the early Eocene period, when the Arctic Ocean became landlocked. A channel that connected the Arctic to the greater oceans got blocked. This provided a tiny fern called Azolla the perfect opportunity to colonize the layer of freshwater that formed on the surface of the Arctic Ocean. The floating plants rapidly covered the water body in thick layers that resembled green blankets.

Gradually, Azolla colonies migrated to every continent with the help of repeated flooding events. For around a million years, they captured more than 80 percent of atmospheric carbon dioxide that got buried at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean as billions of Azolla plants perished.

This “Arctic Azolla event” had devastating impacts on marine life. To date, scientists are trying to figure out how it ended. But they documented that the extraordinary event cooled down the Arctic by at least 40 degrees Fahrenheit — effectively freezing the poles and triggering several cycles of ice ages. “This carbon dioxide sequestration changed the climate from greenhouse to white house,” says Jonathan Bujak, a paleontologist who has researched the Arctic through expeditions since 1973.

Some farmers and scientists, such as Bujak, are looking to this ancient fern, which manipulated the Earth’s climate around 49 million years ago with its insatiable appetite for carbon dioxide, as a potential solution to our modern-day agricultural and environmental challenges. “There is no other plant like Azolla in the world,” says Bujak.

Decoding the Azolla plant

Azolla lives in symbiosis with a cyanobacterium called Anabaena that made the plant’s leaf cavities its permanent home at an early stage in Earth's history. This close relationship with Anabaena enables Azolla to accomplish a feat that is impossible for most plants: directly splitting dinitrogen molecules that make up 78 percent of the Earth’s atmosphere.

A dinitrogen molecule consists of two nitrogen atoms tightly locked together in one of the strongest bonds in nature. The semi-aquatic fern’s ability to split nitrogen, called nitrogen-fixing, made it a highly revered plant in East Asia. Rice farmers used Azolla as a biofertilizer since the 11th century in Vietnam and China.

For decades, scientists have attempted to decode Azolla’s evolution. Cell biologist Francisco Carrapico, who worked at the University of Lisbon, has analyzed this distinctive symbiosis since the 1980s. To his amazement, in 1991, he found that bacteria are the third partner of the Azolla-Anabaena symbiosis.

“Azolla and Anabaena cannot survive without each other. They have co-evolved for 80 million years, continuously exchanging their genetic material with each other,” says Bujak, co-author of The Azolla Story, which he published with his daughter, Alexandra Bujak, an environmental scientist. Three different levels of nitrogen fixation take place within the plant, as Anabaena draws down as much as 2,200 pounds of atmospheric nitrogen per acre annually.

“Using Azolla to mitigate climate change might sound a bit too simple. But that is not the case,” Bujak says. “At a microscopic level, extremely complicated biochemical reactions are constantly occurring inside the plant’s cells that machines or technology cannot replicate yet.”

In 2018, researchers based in the U.S. managed to sequence Azolla’s complete genome — which is four times larger than the human genome — through a crowdfunded study, further increasing our understanding of this plant. “Azolla is a superorganism that works efficiently as a natural biotechnology system that makes it capable of doubling in size within three to five days,” says Carrapico.

Making Azolla mainstream again in agriculture

While scientific groups in the Global North have been working towards unraveling the tiny fern’s inner workings, communities in the Global South are busy devising creative ways to return to their traditional agricultural roots by tapping into Azolla’s full potential.

Pham Gia Minh, an entrepreneur living in Hanoi, Vietnam, is one such citizen scientist who believes that Azolla could be a climate savior. More than two decades after working in finance and business development, Minh is now focusing on continuing his grandfather’s legacy, an agricultural scientist who conducted Azolla research until the 1950s. “Azolla is our family’s heritage,” says Minh.

Pham Gia Minh, an entrepreneur and citizen scientist in Hanoi, Vietnam, believes that Azolla could be a climate savior

Pham Gia Minh

Since the advent of chemical fertilizers in the early 1900s, farmers in Asia abandoned Azolla to save on time and labor costs. But rice farmers in the country went back to cultivating Azolla during the Vietnam War after chemical trade embargoes made chemical fertilizers far too expensive and inaccessible.

By 1973, Azolla cultivation in rice paddy fields was established on half a million hectares in Vietnam. By injecting nitrogen into the soil, Azolla improves soil fertility and also increases rice yields by at least 27 percent compared to urea. The plants can also reduce a farm’s methane emissions by 40 percent.

“Unfortunately, after 1985, chemical fertilizers became cheap and widely available in Vietnam again. So, farmers stopped growing Azolla because of the time-consuming and labor-intensive cultivation process,” says Minh.

Minh has invested in a rural farm where he is proving that modern technology can make the process less burdensome. He uses a pump and drying equipment for harvesting Azolla in a small pond, and he deploys a drone for spraying insecticides and fertilizers on the pond at regular intervals.

As Azolla lacks phosphorus, farmers in developing countries still find it challenging to let go of chemical fertilizers completely. Still, Minh and Bujak say that farmers can use Azolla instead of chemical fertilizers after mixing it with dung.

In the last few years, the fern’s popularity has been growing in other developing countries like India, Palestine, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Bangladesh, where local governments and citizens are trying to re-introduce Azolla integrated farming by growing the ferns in small ponds.

Replacing soybeans with Azolla

In Ecuador, Mariano Montano Armijos, a former chemical engineer, has worked with Azolla for more than 20 years. Since 2008, he has shared resources and information for growing Azolla with 3,000 farmers in Ecuador. The farmers use the harvested plants as a bio-fertilizer and feed for livestock.

“The farmers do not use urea anymore,” says Armijos. “This goes against the conventional agricultural practices of using huge amounts of synthetic nitrogen on a hectare of rice or corn fields.”

He insists that Azolla’s greatest strength is that it is a rich source of proteins, making it highly nutritious for human beings as well. After growing Azolla on a small scale in ponds, Armijos and his business partner, Ivan Noboa, are now building a facility for cultivating the ferns as a superfood on an industrial scale.

According to Armijos, one hectare of Azolla in Ecuador can produce seven tons of proteins. Whereas soybeans produce only one ton of protein per hectare. “If we switch to Azolla, it could help in reducing deforestation in the Amazon. But taming Azolla and turning it into a crop is not easy,” he adds.

Henriette Schluepmann, a molecular plant biologist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, believes that Azolla could replace soybeans and chemical fertilizers someday — only if researchers can achieve yield stability in controlled environments over long durations.

“In a country like the Netherlands that is surrounded by water with high levels of phosphates, it makes sense to grow Azolla as a substitute for soybeans,” says Schluepmann. “For that to happen, we need massive investments to understand these ferns’ reproductive system and how to replicate that within aquaculture systems on a large scale.”

Pollution control and carbon sequestration

Currently, Schluepmann and her team are growing Azolla in a plant nursery or closed system before transferring the ferns to flooded fields. So far, they have been able to continuously grow Azolla without any major setbacks for a total of 155 days. Taking care of these plants’ well-being is an uphill struggle.

Unlike most plants, Azolla does not grow from seeds because it contains female and male spores that tend to split instead of reproducing. To add to that, growing Azolla on a large scale in controlled environments makes the floating plants extremely vulnerable to insect infestations and fungi attacks.

“Even though it is easier to grow Azolla on a non-industrial scale, the long and tedious cultivation process is often in conflict with human rights,” she says. Farms in developing countries such as Indonesia sometimes use child labor for cultivating Azolla.”

History has taught us that the uncontrolled growth of Azolla plants deprives marine ecosystems of sunlight and chokes life underneath them. But researchers like Schluepmann and Bujak are optimistic that even on a much smaller scale, Azolla can put up a fight against human-driven climate change.

Schluepmann discovered an insecticide that can control Azolla blooms. But in the wild, this aquatic fern grows relentlessly in polluted rivers and lakes and has gained a notorious reputation as an invasive weed. Countries like Portugal and the UK banned Azolla after experiencing severe blooms in rivers that snuffed out local marine life.

“Azolla has been misunderstood as a nuisance. But in reality, it is highly beneficial for purifying water,” says Bujak. Through a process called phytoremediation, Azolla locks up pollutants like excess nitrogen and phosphorus and stops toxic algal blooms from occurring in rivers and lakes.

A 2018 study found that Azolla can decrease nitrogen and phosphorus levels in wastewater by 33 percent and 40.5 percent, respectively. While harmful algae like phytoplankton produce toxins and release noxious gases, Azolla automatically blocks any toxins that its cyanobacteria, Anabaena, might produce.

“In our labs, we observed that Azolla works effectively in treating wastewater,” explains Schluepmann. “Once we gain a better understanding of Azolla aquaculture, we can also use it for carbon capture and storage. But in Europe, we would have to use the entire Baltic Sea to make a difference.”

Planting massive amounts of these prehistoric ferns in any of the Northern great water bodies is out of the question. After all, history has taught us that the uncontrolled growth of Azolla plants deprives marine ecosystems of sunlight and chokes life underneath them. But researchers like Schluepmann and Bujak are optimistic that even on a much smaller scale, Azolla can put up a fight against human-driven climate change.

Traditional carbon capture and storage methods are not only expensive but also inefficient and could increase air pollution. According to Bujak’s estimates, Azolla can sequester 10 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide per hectare annually, which is 10 times the average capacity of grasslands.

“Anyone can set up their own DIY carbon capture and storage system by growing Azolla in shallow water. After harvesting and compressing the plants, carbon dioxide gets stored permanently,” says Bujak.

He envisions scaling up this process by setting up “Azolla hubs” in mega-cities where the plants are grown in shallow trays stacked on top of each other with vertical farming systems built within multi-story buildings. The compressed Azolla plants can then be converted into a biofuel, fertilizer, livestock feed, or biochar for sequestering carbon dioxide.

“Using Azolla to mitigate climate change might sound a bit too simple. But that is not the case,” Bujak adds. “At a microscopic level, extremely complicated biochemical reactions are constantly occurring inside the plant’s cells that machines or technology cannot replicate yet.”

Through Azolla, scientists hope to work with nature by tapping into four billion years of evolution.