Why you should (virtually) care

Virtual-first care, or V1C, could increase the quality of healthcare and make it more patient-centric by letting patients combine in-person visits with virtual options such as video for seeing their care providers.

As the pandemic turns endemic, healthcare providers have been eagerly urging patients to return to their offices to enjoy the benefits of in-person care.

But wait.

The last two years have forced all sorts of organizations to be nimble, adaptable and creative in how they work, and this includes healthcare providers’ efforts to maintain continuity of care under the most challenging of conditions. So before we go back to “business as usual,” don’t we owe it to those providers and ourselves to admit that business as usual did not work for most of the people the industry exists to help? If we’re going to embrace yet another period of change – periods that don’t happen often in our complex industry – shouldn’t we first stop and ask ourselves what we’re trying to achieve?

Certainly, COVID has shown that telehealth can be an invaluable tool, particularly for patients in rural and underserved communities that lack access to specialty care. It’s also become clear that many – though not all – healthcare encounters can be effectively conducted from afar. That said, the telehealth tactics that filled the gap during the pandemic were largely stitched together substitutes for existing visit-based workflows: with offices closed, patients scheduled video visits for help managing the side effects of their blood pressure medications or to see their endocrinologist for a quarterly check-in. Anyone whose children slogged through the last year or two of remote learning can tell you that simply virtualizing existing processes doesn’t necessarily improve the experience or the outcomes!

But what if our approach to post-pandemic healthcare came from a patient-driven perspective? We have a fleeting opportunity to advance a care model centered on convenient and equitable access that first prioritizes good outcomes, then selects approaches to care – and locations – tailored to each patient. Using the example of education, imagine how effective it would be if each student, regardless of their school district and aptitude, received such individualized attention.

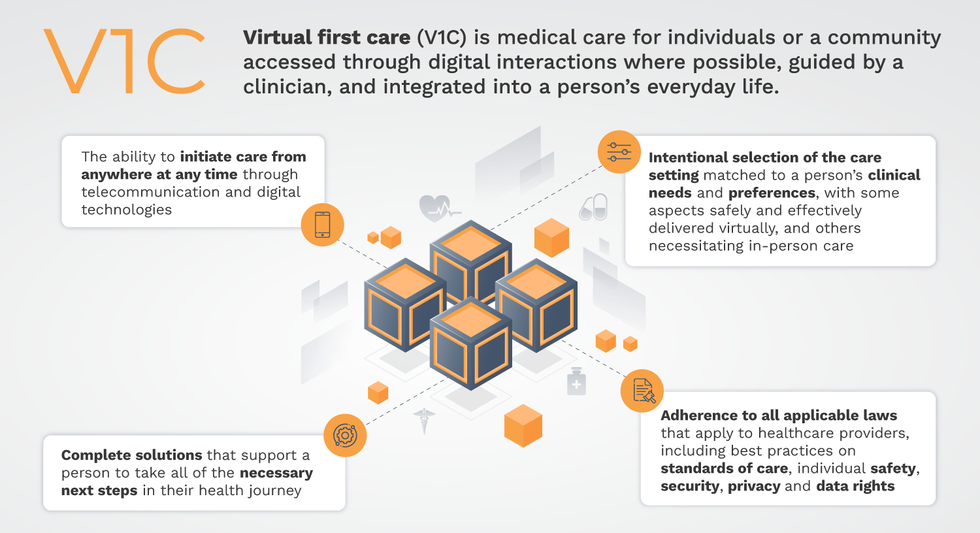

That’s the idea behind virtual-first care (V1C), a new care model centered on convenient, customized, high-quality care that integrates a full suite of services tailored directly to patients’ clinical needs and preferences. This package includes asynchronous communication such as texting; video and other live virtual modes; and in-person options.

V1C goes beyond what you might think of as standard “telehealth” by using evidence-based protocols and tools that include traditional and digital therapeutics and testing, personalized care plans, dynamic patient monitoring, and team-based approaches to care. This could include spit kits mailed for laboratory tests and complementing clinical care with health coaching. V1C also replaces some in-person exams with ongoing monitoring, using sensors for more ‘whole person’ care.

Amidst all this momentum, we have the opportunity to rethink the goals of healthcare innovation, but that means bringing together key stakeholders to demonstrate that sustainable V1C can redefine healthcare.

Established V1C healthcare providers such as Omada, Headspace, and Heartbeat Health, as well as emerging market entrants like Oshi, Visana, and Wellinks, work with a variety of patients who have complicated long-term conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, gastrointestinal illness, endometriosis, and COPD. V1C is comprehensive in ways that are lacking in digital health and its other predecessors: it has the potential to integrate multiple data streams, incorporate more frequent touches and check-ins over time, and manage a much wider range of chronic health conditions, improving lives and reducing disease burden now and in the future.

Recognizing the pandemic-driven interest in virtual care, significant energy and resources are already flowing fast toward V1C. Some of the world’s largest innovators jumped into V1C early on: Verily, Alphabet’s Life Sciences Company, launched Onduo in 2016 to disrupt the diabetes healthcare market, and is now well positioned to scale its solutions. Major insurers like Aetna and United now offer virtual-first plans to members, responding as organizations expand virtual options for employees. Amidst all this momentum, we have the opportunity to rethink the goals of healthcare innovation, but that means bringing together key stakeholders to demonstrate that sustainable V1C can redefine healthcare.

That was the immediate impetus for IMPACT, a consortium of V1C companies, investors, payers and patients founded last year to ensure access to high-quality, evidence-based V1C. Developed by our team at the Digital Medicine Society (DiMe) in collaboration with the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), IMPACT has begun to explore key issues that include giving patients more integrated experiences when accessing both virtual and brick-and-mortar care.

Digital Medicine Society

V1C is not, nor should it be, virtual-only care. In this new era of hybrid healthcare, success will be defined by how well providers help patients navigate the transitions. How do we smoothly hand a patient off from an onsite primary care physician to, say, a virtual cardiologist? How do we get information from a brick-and-mortar to a digital portal? How do you manage dataflow while still staying HIPAA compliant? There are many complex regulatory implications for these new models, as well as an evolving landscape in terms of privacy, security and interoperability. It will be no small task for groups like IMPACT to determine the best path forward.

None of these factors matter unless the industry can recruit and retain clinicians. Our field is facing an unprecedented workforce crisis. Traditional healthcare is making clinicians miserable, and COVID has only accelerated the trend of overworked, disenchanted healthcare workers leaving in droves. Clinicians want more interactions with patients, and fewer with computer screens – call it “More face time, less FaceTime.” No new model will succeed unless the industry can more efficiently deploy its talent – arguably its most scarce and precious resource. V1C can help with alleviating the increasing burden and frustration borne by individual physicians in today’s status quo.

In healthcare, new technological approaches inevitably provoke no shortage of skepticism. Past lessons from Silicon Valley-driven fixes have led to understandable cynicism. But V1C is a different breed of animal. By building healthcare around the patient, not the clinic, V1C can make healthcare work better for patients, payers and providers. We’re at a fork in the road: we can revert back to a broken sick-care system, or dig in and do the hard work of figuring out how this future-forward healthcare system gets financed, organized and executed. As a field, we must find the courage and summon the energy to embrace this moment, and make it a moment of change.

Avalanche rescue dogs train to find and dig out people buried in snow slides

Two-and-a-half year-old Huckleberry, a blue merle Australian shepherd, pulls hard at her leash; her yelps can be heard by skiers and boarders high above on the chairlift that carries them over the ski patrol hut to the top of the mountain. Huckleberry is an avalanche rescue dog — or avy dog, for short. She lives and works with her owner and handler, a ski patroller at Breckenridge Ski Resort in Colorado. As she watches the trainer play a game of hide-and-seek with six-month-old Lume, a golden retriever and avy dog-in-training, Huckleberry continues to strain on her leash; she loves the game. Hide-and-seek is one of the key training methods for teaching avy dogs the rescue skills they need to find someone caught in an avalanche — skier, snowmobiler, hiker, climber.

Lume’s owner waves a T-shirt in front of the puppy. While another patroller holds him back, Lume’s owner runs away and hides. About a minute later — after a lot of barking — Lume is released and commanded to “search.” He springs free, running around the hut to find his owner who reacts with a great amount of excitement and fanfare. Lume’s scent training will continue for the rest of the ski season (Breckenridge plans operating through May or as long as weather permits) and through the off-season. “We make this game progressively harder by not allowing the dog watch the victim run away,” explains Dave Leffler, Breckenridge's ski patroller and head of the avy dog program, who has owned, trained and raised many of them. Eventually, the trainers “dig an open hole in the snow to duck out of sight and gradually turn the hole into a cave where the dog has to dig to get the victim,” explains Leffler.

By the time he is three, Lume, like Huckleberry, will be a fully trained avy pup and will join seven other avy dogs on Breckenridge ski patrol team. Some of the team members, both human and canine, are also certified to work with Colorado Rapid Avalanche Deployment, a coordinated response team that works with the Summit County Sheriff’s office for avalanche emergencies outside of the ski slopes’ boundaries.

There have been 19 avalanche deaths in the U.S. this season, according to avalanche.org, which tracks slides; eight in Colorado. During the entirety of last season there were 17. Avalanche season runs from November through June, but avalanches can occur year-round.

High tech and high stakes

Complementing avy dogs’ ability to smell people buried in a slide, avalanche detection, rescue and recovery is becoming increasingly high tech. There are transceivers, signal locators, ground scanners and drones, which are considered “games changers” by many in avalanche rescue and recovery

For a person buried in an avalanche, the chance of survival plummets after 20 minutes, so every moment counts.

A drone can provide thermal imaging of objects caught in a slide; what looks like a rock from far away might be a human with a heat signature. Transceivers, also known as beacons, send a signal from an avalanche victim to a companion. Signal locators, like RECCO reflectors which are often sewn directly into gear, can echo back a radar signal sent by a detector; most ski resorts have RECCO detector units.

Research suggests that Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), an electromagnetic tool used by geophysicists to pull images from inside the ground, could be used to locate an avalanche victim. A new study from the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories suggests that a computer program developed to pinpoint the source of a chemical or biological terrorist attack could also be used to find someone submerged in an avalanche. The search algorithm allows for small robots (described as cockroach-sized) to “swarm” a search area. Researchers say that this distributed optimization algorithm can help find avalanche victims four times faster than current search mechanisms. For a person buried in an avalanche, the chance of survival plummets after 20 minutes, so every moment counts.

An avy dog in training is picking up scent

Sarah McLear

While rescue gear has been evolving, predicting when a slab will fall remains an emerging science — kind of where weather forecasting science was in the 1980s. Avalanche forecasting still relies on documenting avalanches by going out and looking,” says Ethan Greene, director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC). “So if there's a big snowstorm, and as you might remember, most avalanches happened during snowstorms, we could have 10,000 avalanches that release and we document 50,” says Greene. “Avalanche forecasting is essentially pattern recognition,” he adds--and understanding the layering structure of snow.

However, determining where the hazards lie can be tricky. While a dense layer of snow over a softer, weaker layer may be a recipe for an avalanche, there’s so much variability in snowpack that no one formula can predict the trigger. Further, observing and measuring snow at a single point may not be representative of all nearby slopes. Finally, there’s not enough historical data to help avalanche scientists create better prediction models.

That, however, may be changing.

Last year, an international group of researchers created computer simulations of snow cover using 16 years of meteorological data to forecast avalanche hazards, publishing their research in Cold Regions Science and Technology. They believe their models, which categorize different kinds of avalanches, can support forecasting and determine whether the avalanche is natural (caused by temperature changes, wind, additional snowfall) or artificial (triggered by a human or animal).

With smell receptors ranging from 800 million for an average dog, to 4 billion for scent hounds, canines remain key to finding people caught in slides.

With data from two sites in British Columbia and one in Switzerland, researchers built computer simulations of five different avalanche types. “In terms of real time avalanche forecasting, this has potential to fill in a lot of data gaps, where we don't have field observations of what the snow looks like,” says Simon Horton, a postdoctoral fellow with the Simon Fraser University Centre for Natural Hazards Research and a forecaster with Avalanche Canada, who participated in the study. While complex models that simulate snowpack layers have been around for a few decades, they weren’t easy to apply until recently. “It's been difficult to find out how to apply that to actual decision-making and improving safety,” says Horton. If you can derive avalanche problem types from simulated snowpack properties, he says, you’ll learn “a lot about how you want to manage that risk.”

The five categories include “new snow,” which is unstable and slides down the slope, “wet snow,” when rain or heat makes it liquidly, as well as “wind-drifted snow,” “persistent weak layers” and “old snow.” “That's when there's some type of deeply buried weak layer in the snow that releases without any real change in the weather,” Horton explains. “These ones tend to cause the most accidents.” One step by a person on that structurally weak layer of snow will cause a slide. Horton is hopeful that computer simulations of avalanche types can be used by scientists in different snow climates to help predict hazard levels.

Greene is doubtful. “If you have six slopes that are lined up next to each other, and you're going to try to predict which one avalanches and the exact dimensions and what time, that's going to be really hard to do. And I think it's going to be a long time before we're able to do that,” says Greene.

What both researchers do agree on, though, is that what avalanche prediction really needs is better imagery through satellite detection. “Just being able to count the number of avalanches that are out there will have a huge impact on what we do,” Greene says. “[Satellites] will change what we do, dramatically.” In a 2022 paper, scientists at the University of Aberdeen in England used satellites to study two deadly Himalayan avalanches. The imaging helped them determine that sediment from a 2016 ice avalanche plus subsequent snow avalanches contributed to the 2021 avalanche that caused a flash flood, killing over 200 people. The researchers say that understanding the avalanches characteristics through satellite imagery can inform them how one such event increases the magnitude of another in the same area.

Avy dogs trainers hide in dug-out holes in the snow, teaching the dogs to find buried victims

Sarah McLear

Lifesaving combo: human tech and Mother Nature’s gear

Even as avalanche forecasting evolves, dogs with their built-in rescue mechanisms will remain invaluable. With smell receptors ranging from 800 million for an average dog, to 4 billion for scent hounds, canines remain key to finding people caught in slides. (Humans in comparison, have a meager 12 million.) A new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience revealed that in dogs smell and vision are connected in the brain, which has not been found in other animals. “They can detect the smell of their owner's fingerprints on a glass slide six weeks after they touched it,” says Nicholas Dodman, professor emeritus at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. “And they can track from a boat where a box filled with meat was buried in the water, 100 feet below,” says Dodman, who is also co-founder and president of the Center for Canine Behavior Studies.

Another recent study from Queens College in Belfast, United Kingdom, further confirms that dogs can smell when humans are stressed. They can also detect the smell of a person’s breath and the smell of the skin cells of a deceased person.

The emerging avalanche-predicting human-made tech and the incredible nature-made tech of dogs’ olfactory talents is the lifesaving “equipment” that Leffler believes in. Even when human-made technology develops further, it will be most efficient when used together with the millions of dogs’ smell receptors, Leffler believes. “It is a combination of technology and the avalanche dog that will always be effective in finding an avalanche victim.”

Living with someone changes your microbiome, new research shows

For the first time, research has shown that bacteria of the microbiome are transmitted between many individuals, not just infants and their mothers, in ways that can’t be explained by having the same diet or geography.

Some roommate frustration can be expected, whether it’s a sink piled high with crusty dishes or crumbs where a clean tabletop should be. Now, research suggests a less familiar issue: person-to-person transmission of shared bacterial strains in our gut and oral microbiomes. For the first time, the lab of Nicola Segata, a professor of genetics and computational biology at the University of Trento, located in Italy, has shown that bacteria of the microbiome are transmitted between many individuals, not just infants and their mothers, in ways that can’t be explained by their shared diet or geography.

It’s a finding with wide-ranging implications, yet frustratingly few predictable outcomes. Our microbiomes are an ever-growing and changing collection of helpful and harmful bacteria that we begin to accumulate the moment we’re born, but experts are still struggling to unravel why and how bacteria from one person’s gut or mouth become established in another person’s microbiome, as opposed to simply passing through.

“If we are looking at the overall species composition of the microbiome, then there is an effect of age of course, and many other factors,” Segata says. “But if we are looking at where our strains are coming from, 99 percent of them are only present in other people’s guts. They need to come from other guts.”

If we could better understand this process, we might be able to control and use it; perhaps hospital patients could avoid infections from other patients when their microbiome is depleted by antibiotics and their immune system is weakened, for example. But scientists are just beginning to link human microbiomes with various ailments. Growing evidence shows that our microbiomes steer our long-term health, impacting conditions like obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cancer.

Previous work from Segata’s lab and others illuminated the ways bacteria are passed from mothers to infants during the first few months of life during vaginal birth, breastfeeding and other close contact. And scientists have long known that people in close proximity tend to share bacteria. But the factors related to that overlap, such as genetics and diet, were unclear, especially outside the mother-baby dyad.

“If we look at strain sharing between a mother and an infant at five years of age, for example, we cannot really tell which was due to transmission at birth and which is due to continued transmission because of contact,” Segata says. Experts hypothesized that they could be caused by bacterial similarities in the environment itself, genetics, or bacteria from shared foods that colonized the guts of people in close contact.

Strain sharing was highest in mother-child pairs, with 96 percent of them sharing strains, and only slightly lower in members of shared households, at 95 percent.

In Italy, researchers led by Mireia Valles-Colomer, including Segata, hoped to unravel this mystery. They compared data from 9,715 stool and saliva samples in 31 genomic datasets with existing metadata. Scientists zoomed in on variations in each bacterial strain down to the individual level. They examined not only mother-child pairs, but people living in the same household, adult twins, and people living in the same village in a level of detail that wasn’t possible before, due to its high cost and difficulties in retrieving data about interactions between individuals, Segata explained.

“This paper is, with high granularity, quantifying the percent sharing that you expect between different types of social interactions, controlling for things like genetics and diet,” Gibbons says. Strain sharing was highest in mother-child pairs, with 96 percent of them sharing strains, and only slightly lower in members of shared households, at 95 percent. And at least half of the mother-infant pairs shared 30 percent of their strains; the median was 12 percent among people in shared households. Yet, there was no sharing among eight percent of adult twins who lived separately, and 16 percent of people within villages who resided in different households. The results were published in Nature.

It’s not a regional phenomenon. Although the types of bacterial strains varied depending on whether people lived in western and eastern nations — datasets were drawn from 20 countries on five continents — the patterns of sharing were much the same. To establish these links, scientists focused on individual variations in shared bacterial strains, differences that create unique bacterial “fingerprints” in each person, while controlling for variables like diet, demonstrating that the bacteria had been transmitted between people and were not the result of environmental similarities.

The impact of this bacterial sharing isn’t clear, but shouldn’t be viewed with trepidation, according to Sean Gibbons, a microbiome scientist at the nonprofit Institute for Systems Biology.

“The vast majority of these bugs are actually either benign or beneficial to our health, and the fact that we're swapping and sharing them and that we can take someone else's strain and supplement or better diversify our own little garden is not necessarily a bad thing,” he says.

"There are hundreds of billions of dollars of investment capital moving into these microbiome therapeutic companies; bugs as drugs, so to speak,” says Sean Gibbons, a microbiome scientist at the Institute for Systems Biology.

Everyday habits like exercising and eating vegetables promote a healthy, balanced gut microbiome, which is linked to better metabolic and immune function, and fewer illnesses. While many people’s microbiomes contain bacteria like C. diff or E. coli, these bacteria don’t cause diseases in most cases because they’re present in low levels. But a microbiome that’s been wiped out by, say, antibiotics, may no longer keep these bacteria in check, allowing them to proliferate and make us sick.

“A big challenge in the microbiome field is being able to rationally predict whether, if you're exposed to a particular bug, it will stick in the context of your specific microbiome,” Gibbons says.

Gibbons predicts that explorations of microbe-based therapeutics will be “exploding” in the coming decades. “There are hundreds of billions of dollars of investment capital moving into these microbiome therapeutic companies; bugs as drugs, so to speak,” he says. Rather than taking a mass-marketed probiotic, a precise understanding of an individual’s microbiome could help target the introduction of just the right bacteria at just the right time to prevent or treat a particular illness.

Because the current study did not differentiate between different types of contact or relationships among household members sharing bacterial strains or determine the direction of transmission, Segata says his current project is examining children in daycare settings and tracking their microbiomes over time to understand the role genetics and everyday interactions play in the level of transmission that occurs.

This relatively newfound ability to trace bacterial variants to minute levels has unlocked the chance for scientists to untangle when and how bacteria leap from one microbiome to another. As researchers come to better understand the factors that permit a strain to establish itself within a microbiome, they could uncover new strategies to control these microbes, harnessing the makeup of each microbiome to help people to resist life-altering medical conditions.