Virtual Clinical Trials Are Letting More People of Color Participate in Research

Virtual clinical trials are helping to eradicate logistical barriers to clinical trial participation, though trust is still an issue.

Herman Taylor, director of the cardiovascular research institute at Morehouse college, got in touch with UnitedHealth Group early in the pandemic.

The very people who most require solutions to COVID are those who are least likely to be involved in the search to find them.

A colleague he worked with at Grady Hospital in Atlanta was the guy when it came to studying sickle cell disease, a recessive genetic disorder that causes red blood cells to harden into half-moon shapes, causing cardiovascular problems. Sickle cell disease is more common in African Americans than it is in Caucasians, in part because having just one gene for the disease, called sickle cell trait, is protective against malaria, which is endemic to much of Africa. Roughly one in 12 African Americans carry sickle cell trait, and Taylor's colleague wondered if this could be one factor affecting differential outcomes for COVID-19.

UnitedHealth Group granted Taylor and his colleague the money to study sickle cell trait in COVID, and then, as they continued working together, they began to ask Taylor his opinion on other topics. As an insurance company, United had realized early in the pandemic that it was sitting on a goldmine of patient data—some 120 million patients' worth—that it could sift through to look for potential COVID treatments.

Their researchers thought they had found one: In a small subset of 14,000 people who'd contracted COVID, there was a group whose bills were paid by Medicare (which the researchers took as a proxy for older age). The people in this group who were taking ACE inhibitors, blood vessel dilators often used to treat high blood pressure, were 40 percent less likely to be hospitalized than those who were not taking the drug.

The connection between ACE inhibitors and COVID hospitalizations was a correlation, a statistical association. To determine whether the drugs had any real effect on COVID outcomes, United would have to perform another, more rigorous study. They would have to assign some people to receive small doses of ACE inhibitors, and others to receive placebos, and measure the outcomes under each condition. They planned to do this virtually, allowing study participants to sign up and be screened online, and sending drugs, thermometers, and tests through the mail. There were two reasons to do it this way: First, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had been advising medical researchers to embrace new strategies in clinical trials as a way to protect participants during the pandemic.

The second reason was why they asked Herman Taylor to co-supervise it: Clinical trials have long had a diversity problem. And going virtual is a potential solution.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, COVID-19 has infected people of color at a rate of three times that of Caucasians (killing Black people at a rate 2.5 times as high, and Hispanic and American Indian or Alaska Native people at a rate 1.3 times as high). A number of explanations have been put forth to explain this disproportionate toll. Among them: higher levels of poverty, essential jobs that increase exposure, and lower quality or inadequate access to medical care.

Unfortunately, these same factors also affect who participates in research. People of color may be less likely to have doctors recommend studies to them. They may not have the time or the resources to hang out in a waiting room for hours. They may not live near large research institutions that conduct trials. The result is that new treatments, even for diseases that affect Latin, Native American, or African American populations in greater proportions, are studied mostly in white volunteers. The very people who most require solutions to COVID are those who are least likely to be involved in the search to find them.

Virtual trials can alleviate a number of these problems. Not only can people find and request to participate in these types of trials through their phones or computers, virtual trials also cover more costs, include a larger geographical range, and have inherently flexible hours.

"[In a traditional study] you have to go to a doctor's office to enroll and drive a couple of hours and pay $20 for parking and pay $15 for a sandwich in the hospital cafeteria and arrange for daycare for your kids and take time off of work," says Dr. Jonathan Cotliar, chief medical officer of Science37, a platform that investigators can hire to host and organize their trials virtually. "That's a lot just for one visit, much less over the course of a six to 12-month study."

Cotliar's data suggests that virtual trials' enhanced access seriously affects the racial makeup of a given study's participant pool. Sixty percent of patients enrolled in Science37 trials are non-Caucasian, which is, Cotliar says, "staggering compared to what you find in traditional site-based research."

But access is not the only barrier to including more people of color in clinical trials. There is also trust. When agreeing to sign up for research, undocumented immigrants may worry about finding themselves in legal trouble or without any medical support should something go wrong. In a country with a history of experimenting on African Americans without their consent, black people may not trust institutions not to use them as guinea pigs.

"A lot of people report being somewhat disregarded or disrespected once entering the healthcare system," Taylor says. "You take it all together, then people wonder, well, okay, this is how the system tends to regard me, yet now here come these people doing research, and they're all about getting me into their studies." Not so surprising that a lot of people may respond with a resounding "No thanks."

United's ACE inhibitor trial was notable for addressing both of these challenges. In addition to covering costs and allowing study subjects to participate from their own homes, it was being co-sponsored by a professor at Morehouse, one of the country's historic black colleges and universities (often abbreviated HBCUs). United was recruiting heavily in Atlanta, whose population is 52 percent African American. The study promised a thoughtful introduction to a more egalitarian future of medical research.

There's just one problem: It isn't going to happen.

This month, in preparation for the study, United reanalyzed their ACE inhibitor data with all the new patients who'd contracted COVID in the months since their first analysis. Their original data set had been concentrated in the Northeast, mostly New York City, where the earliest outbreak took place. In the 12 weeks it had taken them to set up the virtual followup study, epicenters had shifted. United's second, more geographically comprehensive sample had ten times the number of people in it. And in that sample, the signal simply disappeared.

"I was shocked, but that's the reality," says Deneen Vojta, executive vice president of enterprise research and development for UnitedHealth Group. "You make decisions based on the data, but when you get more data, more information, you might make a different decision. The answer is the answer."

There was no point in running a virtual ACE inhibitor study if a larger, more representative sample of people indicated the drug was unlikely to help anyone. Still, the model United had established to run the trial remains viable. Even as she scrapped the ACE inhibitor study, Vojta hoped not just to continue United's relationship with Dr. Taylor and Morehouse, but to formalize it. Virtual platforms are still an important part of their forthcoming trials.

If people don't believe a vaccine has been created with them in mind, then they won't take it, and it won't matter whether it exists or not.

United is not alone in this approach. As phase three trials for vaccines against SARS CoV-2 get underway, big pharma companies have been publicly articulating their own strategies for including more people of color in clinical trials, and many of these include virtual elements. Janelle Sabo, global head of clinical innovation, systems and clinical supply chain at Eli Lilly, told me that the company is employing home health and telemedicine, direct-to-patient shipping and delivery, and recruitment using social media and geolocation to expand access to more diverse populations.

Dr. Macaya Douoguih, Head of Clinical Development and Medical Affairs for Janssen Vaccines under Johnson & Johnson, spoke to Congress about this issue during a July hearing before the House Energy and Commerce Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee. She said that the company planned to institute a "focused digital and community outreach plan to provide resources and opportunities to encourage participation in our clinical trials," and had partnered with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health "to understand how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting different communities in the United States."

But while some of these plans are well thought-out, others are concerningly nebulous, featuring big pronouncements but fewer tangible strategies. In that same July hearing, Massachusetts representative Joe Kennedy III (D) sounded like a frustrated teacher when admonishing four of the five leads of the present pharma companies (AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Moderna, and Pfizer) for not explaining exactly how they'd ensure diversity both in the study of their vaccines, and in their eventual distribution.

This matters: The uptake of the flu vaccine is 10 percentage points lower in both the African American and Hispanic communities than it is in Caucasians. A Pew research study conducted early in the pandemic found that just 54 percent of Black adults said they "would definitely or probably get a coronavirus vaccine," compared to 74 percent of Whites and Hispanics.

"As a good friend of mine, Dr. [James] Hildreth, president at Meharry, another HBC medical school, likes to say: 'A vaccine is great, but it is the vaccination that saves people,'" Taylor says. If people don't believe a vaccine has been created with them in mind, then they won't take it, and it won't matter whether it exists or not.

In this respect, virtual platforms remain an important first step, at least in expanding admittance. In June, United Health opened up a trial to their entire workforce for a computer game that could treat ADHD. In less than two months, 1,743 people had signed up for it, from all different socioeconomic groups, from all over the country. It was inching closer to the kind of number you need for a phase three vaccine trial, which can require tens of thousands of people. Back when they'd been planning the ACE inhibitor study, United had wanted 9,600 people to agree to participate.

Now, with the help of virtual enrollment, they hope they can pull off similarly high numbers for the COVID vaccine trial they will be running for an as-yet-unnamed pharmaceutical partner. It stands to open in September.

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

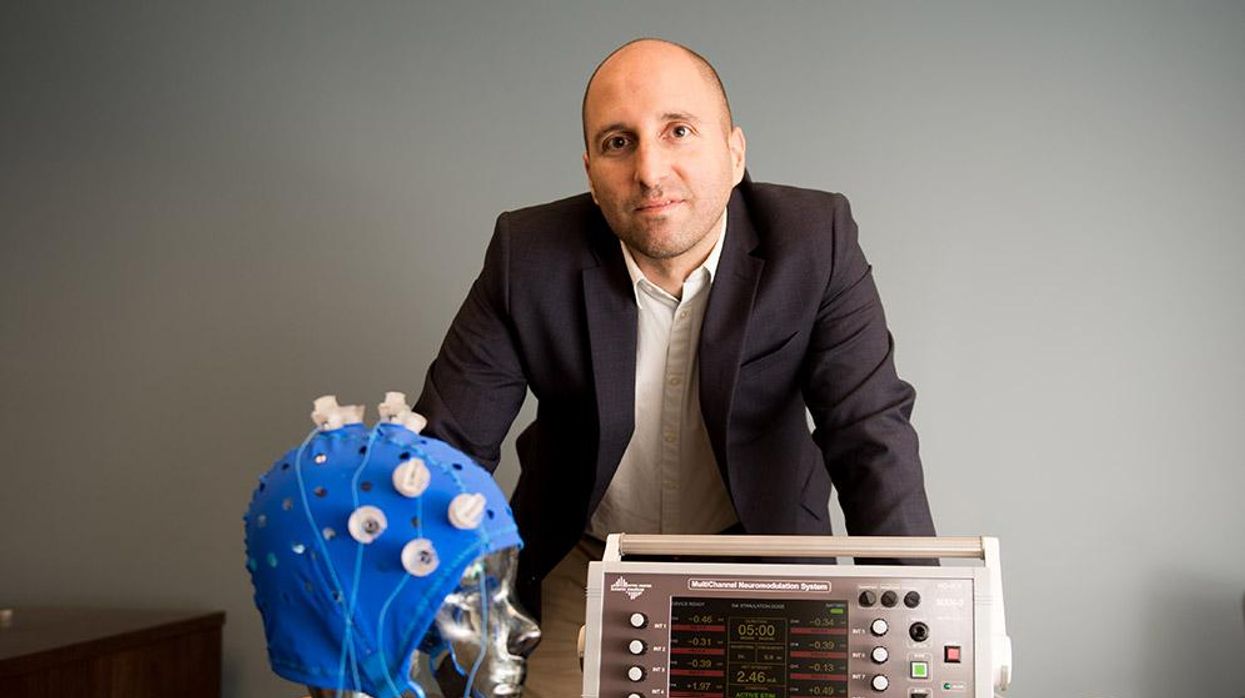

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”