Virtual Reality is Making Medical Care for Kids Less Scary and Painful

A patient at Children's Hospital Los Angeles (Courtesy of Children's Hospital Los Angeles) plus Bear Blast, developed by AppliedVR.

A blood draw is not normally a fun experience, but these days, virtual reality technology is changing that.

Instead of watching a needle go into his arm, a child wearing a VR headset at Children's Hospital Los Angeles can play a game throwing balls at cartoon bears. In Seattle, at the University of Washington, a burn patient can immerse herself in a soothing snow scene. And at the University of Miami Hospital, a five-minute skin biopsy can become an exciting ride at an amusement park.

VR is transforming once-frightening medical encounters for kids, from blood draws to biopsies to pre-surgical prep, into tolerable ones.

It's literally a game changer, says pediatric neurosurgeon Kurtis Auguste, who uses the tool to help explain pending operations to his young patients and their families. The virtual reality 3-D portrait of their brain is recreated from an MRI, originally to help plan the surgery. The image of normally bland tissue is painted with false colors to better see the boundaries and anomalies of each component. It can be rotated, viewed from every possible angle, zoomed in and out; incisions can be made and likely results anticipated. Auguste has extended its use to patients and families.

"The moment you put these headsets on the kids, we immediately have a link, because honestly, this is how they communicate with each other," says Auguste. "We're all sitting around the table playing games. It's really bridged the distance between me, the pediatric specialist, and my patients" at the Benioff Children's Hospital Oakland, now affiliated with the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

The VR experience engages people where they are, immersing them in the environment rather than lecturing them. And it seems to work in all environments, across age and cultural differences, leading to a better grasp of what will be undertaken. That understanding is crucial to meaningful informed consent for surgery. It is particularly relevant for safety-net hospitals, which includes most children's hospitals, because often members of the families were born elsewhere and may have limited understanding of English, not to mention advanced medicine.

Targeting pain

"We're trying to target ways that we can decrease pain, anxiety, fear – what people usually experience as a function of a needle," says Jeffrey Gold, a pioneer in adapting VR at Children's Hospital Los Angeles. He ran the pain clinic there and in 2004 initially focused on phlebotomy, simple blood draws. Many of their kids require frequent blood draws to monitor serious chronic conditions such as diabetes, HIV infection, sickle cell disease, and other conditions that affect the heart, liver, kidneys and other organs.

The scientific explanation of how VR works for pain relief draws upon two basic principles of brain function. The first is "top down inhibition," Gold explains. "We all have the inherent capacity to turn down signals once we determine that signal is no longer harmful, dangerous, hurtful, etc. That's how our brain operates on purpose. It's not just a distraction, it's actually your brain stopping the pain signal at the spinal cord before it can fire all the way up to the frontal lobe."

Second is the analgesic effect from endorphins. "If you're in a gaming environment, and you're having fun and you're laughing and giggling, you are actually releasing endorphins...a neurochemical reaction at the synaptic level of the brain," he says.

Part of what makes VR effective is "what's called a cognitive load, where you have to actually learn something and do something," says Gold. He has worked with developers on a game call Bear Blast, which has proven to be effective in a clinical trial for mitigating pain. But he emphasizes, it is not a one-size-fits all; the programs and patients need to be evaluated to understand what works best for each case.

Gold was a bit surprised to find that VR "actually facilitates quicker blood draws," because the staff doesn't have to manage the kids' anxiety, so "they require fewer needle sticks." The kids, parents, and staff were all having a good time, "and that's a big win when everybody is benefiting." About two years ago the hospital made VR an option that patients can request in the phlebotomy lab, and about half of kids age 4 and older choose to do so.

The technology "gets the kids engaged and performing the activity the way we want them to" to maximize recovery.

VR reduces or eliminates the need to use sedation or anesthesia, which carries a small but real risk of an adverse reaction. And important to parents, it eliminates the recovery time from using sedation, which shortens the visit and time missed from school and work.

A more intriguing question is whether reducing fear and anxiety in early-life experiences with the healthcare system through activities like VR will have a long-term affect on kids' attitudes toward medicine as they grow older. "If you're a screaming meemie when you come get your blood draw when you're five or seven, you're still that anxious adolescent or adult who is all quivering and sweating and avoiding healthcare," Gold says. "That's a longitudinal health outcome I'd love to get my hands on in 10-15 years from now."

Broader applications

Dermatologist Hadar Lev-Tov read about the use of VR to treat pain and decided to try it in his practice at the University of Miami Hospital. He thought, "OK, this is low risk, it's easy to do. So we got some equipment and got it done." It was so affordable he paid for it out of his own pocket, rather than wait to go through administrative channels. The results were so interesting that he decided to publish it as a series of case studies with a wide variety of patients and types of procedures.

Some of them, such as freezing off warts, are not particularly painful. "But there can be a lot of anxiety, especially for kids, which can be worse than pain and can disrupt the procedure." It can trigger a non-rational, primal fight or flight response in the limbic region of the brain.

Adults understand the need for a biopsy of a skin growth and tolerate what might be a momentary flick of pain. "But for a kid you think twice about a biopsy, both because it's a hassle and because it could be a traumatic event for a child," says Lev-Tov. VR has helped to allay such fears and improve medical care.

Integrating VR into practice has been relatively easy, primarily focusing on simple training for staff and ensuring that standard infection control practices are used in handling equipment that is used by different patients. More mundane issues are ensuring that the play back and wi-fi equipment are functioning properly. He has had a few complaints from kids when the procedure is competed and the VR is turned off prematurely, which is why he favors programs like a roller coaster ride that lasts about five minutes, ample time to take a biopsy or two.

The future is today

The pediatric neurosurgeon Auguste is collaborating with colleagues at Oakland Children's to expand use of VR into different areas of care. Cancer specialists often use a port, a bubble installed under the skin in the chest of the child, to administer chemotherapy. But the young patient's curiosity often draws their attention downward to the port and their chin can potentially contaminate or obstruct it, interfering with the procedure. So the team developed a VR game involving birds that requires players to move their heads upward, away from the port, improving administration of the drugs and reducing the risk of infection.

Innovative use of VR just may be one tool that actually makes kids eager to visit the doctor.

Other games are being developed for rehabilitation that require the use of specific nerve and muscle combinations. The technology "gets the kids engaged and performing the activity the way we want them to" to maximize recovery, Auguste explains. "We can monitor their progress by the score on the game, and if it plateaus, maybe switch to another game."

Another project is trying to ease the anxiety and confusion of the patient and family experience within the hospital itself. Hospital staff are creating a personalized VR introductory walking tour that leads from the parking garage through the maze of structures and corridors in the hospital complex to Dr. Auguste's office, phlebotomy, the MRI site, and other locations they might visit. The goal is to make them familiar with key landmarks before they even set foot in the facility. "So when they come the day of the visit they have already taken that exact same path, hopefully more than once."

"They don't miss their MRI appointment and therefore they don't miss their clinical appointment with me," says Auguste. It reduces patient anxiety about the encounter and from the hospital's perspective, it will reduce costs of missed and rescheduled visits simply because patients did not go to the right place at the right time.

The VR visit will be emailed to patients ahead of time and they can watch it on a smartphone installed in a disposable cardboard viewer. Oakland Children's hopes to have the system in place by early next year. Auguste says their goal in using VR, like other health care providers across the country, is "to streamline the entire patient experience."

Innovative use of VR just may be one tool that actually makes kids eager to visit the doctor. That would be a boon to kids, parents, and the health of America.

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

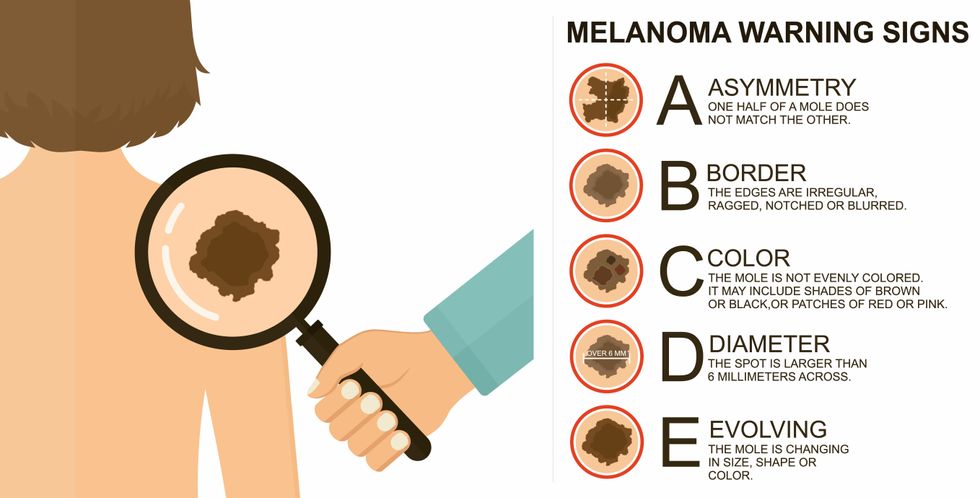

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.