Want to Strengthen American Democracy? The Science of Collaboration Can Help

The science of collaboration explores why diverse individuals choose to work together and how to design systems that encourage successful collaborations.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

American politics has no shortage of ailments. Many do not feel like their voice matters amid the money and influence amassed by corporations and wealthy donors. Many doubt whether elected officials and bureaucrats can or even want to effectively solve problems and respond to citizens' needs. Many feel divided both physically and psychologically, and uncomfortable (if not scared) at the prospect of building new connections across lines of difference.

Strengthening American democracy requires countering these trends. New collaborations between university researchers and community leaders such as elected officials, organizers, and nonprofit directors can help. These collaborations can entail everything from informal exchanges to co-led projects.

But there's a catch. They require that people with diverse forms of knowledge and lived experience, who are often strangers, choose to engage with one another. We know that strangers often remain strangers.

That's why a science of collaboration that centers the inception question is vital: When do diverse individuals choose to work together in the first place? How can we design institutions that encourage beneficial collaborations to arise and thrive? And what outcomes can occur?

How Collaborations Between Researchers and Community Leaders Can Help

First consider the feeling of powerlessness. Individual action becomes more powerful when part of a collective. For ordinary citizens, voting and organizing are arguably the two most impactful forms of collective action, and as it turns out there is substantial research on how to increase turnout and how to build powerful civic associations. Collaborations between researchers familiar with that work and organizers and nonprofit leaders familiar with a community's context can be especially impactful.

For example, in 2019, climate organizers with a nonpartisan group in North Carolina worked with a researcher who studies organizing to figure out how to increase volunteer commitment—that is, how to transform volunteers who only attend meetings into leaders who take responsibility for organizing others. Together, they designed strategies that made sense for the local area. Once implemented, these strategies led to a 161% year-over-year increase in commitment. More concretely, dozens of newly empowered volunteers led events to raise awareness of how climate change was impacting the local community and developed relationships with local officials and business owners, all while coming to see themselves as civic leaders. This experience also fed back into the researcher's work, motivating the design of future studies.

Or consider how researchers and local elected officials can collaborate and respond to novel challenges like the coronavirus. For instance, in March 2020, one county in Upstate New York suddenly had to figure out how to provide vital services like internet and health screenings for residents who could no longer visit shuttered county offices. They turned to a researcher who knew about research on mobile vans. Together, they spoke about the benefits and costs of mobile vans in general, and then segued into a more specific conversation about what routings and services would make sense in this specific locale. Their collaboration entailed a few conversations leading up to the county's decision, and in the end the county received helpful information and the researcher learned about new implementation challenges associated with mobile vans.

In April, legislators in another Upstate New York county realized they needed honest, if biting, feedback from local mayors about their response to the pandemic. They collaborated with researchers familiar with survey methodology. County legislators supplied the goals and historical information about fraught county–city relationships, while researchers supplied evidence-based techniques for conducting interviews in delicate contexts. These interviews ultimately revealed mayors' demand for more up-to-date coronavirus information from the county and also more county-led advocacy at the state level.

To be sure, there are many situations in which elected officials' lack of information is not the main hurdle. Rather, they need an incentive to act. Yet this is another situation in which collaborations between university researchers and community leaders focused on evidence-based, context-appropriate approaches to organizing and voter mobilization could produce needed pressure.

This brings me to the third way in which collaborations between researchers and community leaders can strengthen American democracy. They entail diverse people working to develop a common interest by building new connections across lines of difference. This is a core democratic skill that withers in the absence of practice.

In addition to credibility, we've learned that potential collaborators also care about whether others will be responsive to their goals and constraints, understand their point of view, and will be enjoyable to interact with.

The Science of Collaboration

The previous examples have one thing in common: a collaboration actually took place.

Yet that often does not happen. While there are many reasons why collaborations between diverse people should arise we know far less about when they actually do arise.

This is why a science of collaboration centered on inception is essential. Some studies have already revealed new insights. One thing we've learned is that credibility is important, but often not enough. By credibility, I mean that people are more likely to collaborate when they perceive each other to be trustworthy and have useful information or skills to share. Potential collaborators can signal their credibility by, for instance, identifying shared values and mentioning relevant previous experiences. One study finds that policymakers are more interested in collaborating with researchers who will share findings that are timely and locally relevant—that is, the kind that are most useful to them.

In addition to credibility, we've learned that potential collaborators also care about whether others will be responsive to their goals and constraints, understand their point of view, and will be enjoyable to interact with. For instance, potential collaborators can explicitly acknowledge that they know the other person is busy, or start with a question rather than a statement to indicate being interested. One study finds that busy nonprofit leaders are more likely to collaborate with researchers who explicitly state that (a) they are interested in learning about the leaders' expertise, and (b) they will efficiently share what they know. Another study underscores that potential collaborators need to feel like they know how to interact—that is, to feel like they have a "script" for what's appropriate to say during the interaction.

We're also learning that institutions (such as matchmaking organizations) can reduce uncertainty about credibility and relationality, and also help collaborations start off on the right foot. They are a critical avenue for connecting strangers. For instance, brokers can use techniques that increase the likelihood that diverse people feel comfortable sharing what they know, raising concerns, and being responsive to others.

Looking Ahead

A science of collaboration that centers the inception question is helpful on two levels. First, it provides an evidence base for how to effectively connect diverse people to work together. Second, when applied to university researchers and community leaders, it can produce collaborations that strengthen American democracy. Moreover, these collaborations are easily implemented, especially when informal and beginning as a conversation or two (as in the mobile vans example).

Existing research on the science of collaboration has already yielded actionable insights, yet we still have much to learn. For instance, we need to better understand the latent demand. Interviews that ask a wide variety of community leaders and researchers who have not previously collaborated to talk about why doing so might be helpful would be enlightening. They could also be a useful antidote to the narrative of conflict that often permeates discussions about the role of science in American politics.

In addition, we need to learn more about the downstream consequences of these collaborations, such as whether new networks arise that include colleagues of the initial collaborators. Here, it would be helpful to study the work of brokers – how they introduce people to each other, how much they follow up, and the impact of those decisions.

Ultimately, expanding the evidence base of the science of collaboration, and then directly applying what we learn, will provide important new and actionable avenues for strengthening American democracy.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

A startup aims to make medicines in space

A company is looking to improve medicines by making them in the nearly weightless environment of space.

Story by Big Think

On June 12, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket deployed 72 small satellites for customers — including the world’s first space factory.

The challenge: In 2019, pharma giant Merck revealed that an experiment on the International Space Station had shown how to make its blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda more stable. That meant it could now be administered via a shot rather than through an IV infusion.

The key to the discovery was the fact that particles behave differently when freed from the force of gravity — seeing how its drug crystalized in microgravity helped Merck figure out how to tweak its manufacturing process on Earth to produce the more stable version.

Microgravity research could potentially lead to many more discoveries like this one, or even the development of brand-new drugs, but ISS astronauts only have so much time for commercial experiments.

“There are many high-performance products that are only possible to make in zero-gravity, which is a manufacturing capability that cannot be replicated in any factory on Earth.”-- Will Bruey.

The only options for accessing microgravity (or free fall) outside of orbit, meanwhile, are parabolic airplane flights and drop towers, and those are only useful for experiments that require less than a minute in microgravity — Merck’s ISS experiment took 18 days.

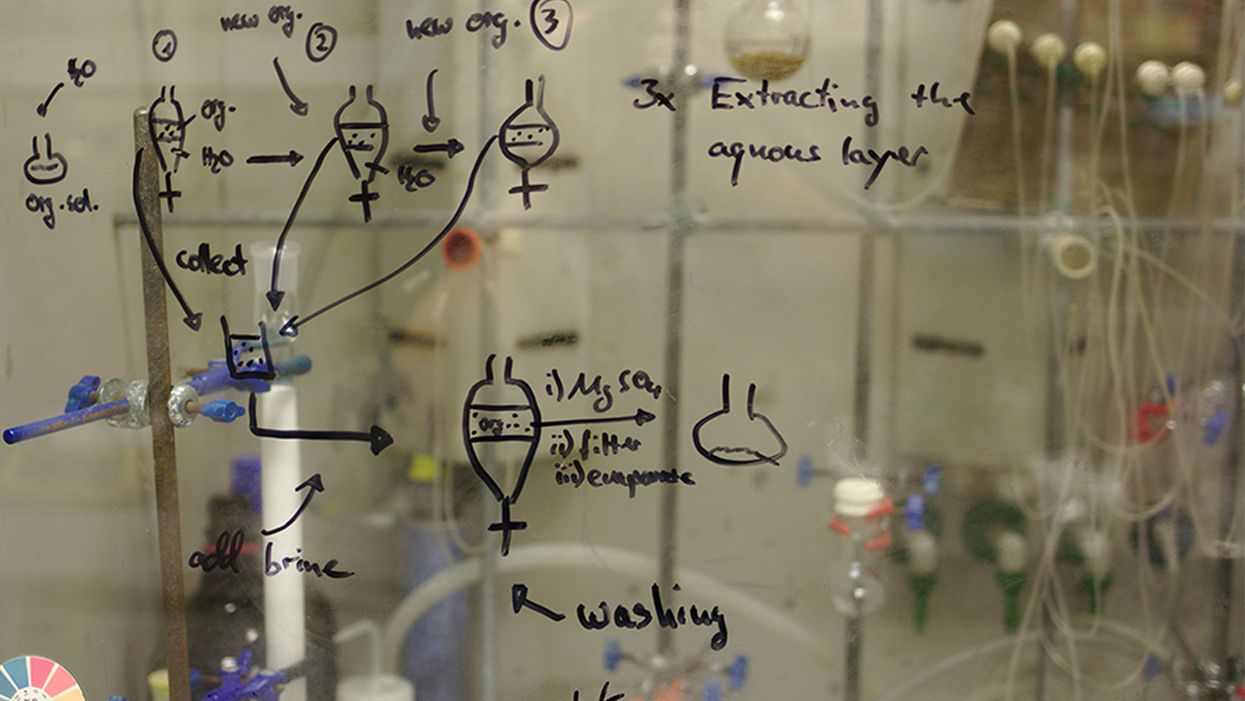

The idea: In 2021, California startup Varda Space Industries announced its intention to build the world’s first space factory, to manufacture not only pharmaceuticals but other products that could benefit from being made in microgravity, such as semiconductors and fiber optic cables.

This factory would consist of a commercial satellite platform attached to two Varda-made modules. One module would contain equipment capable of autonomously manufacturing a product. The other would be a reentry capsule to bring the finished goods back to Earth.

“There are many high-performance products that are only possible to make in zero-gravity, which is a manufacturing capability that cannot be replicated in any factory on Earth,” said CEO Will Bruey, who’d previously developed and flown spacecraft for SpaceX.

“We have a team stacked with aerospace talent in the prime of their careers, focused on getting working hardware to orbit as quickly as possible,” he continued.

“[Pharmaceuticals] are the most valuable chemicals per unit mass. And they also have a large market on Earth.” -- Will Bruey, CEO of Varda Space.

What’s new? At the time, Varda said it planned to launch its first space factory in 2023, and, in what feels like a first for a space startup, it has actually hit that ambitious launch schedule.

“We have ACQUISITION OF SIGNAL,” the startup tweeted soon after the Falcon 9 launch on June 12. “The world’s first space factory’s solar panels have found the sun and it’s beginning to de-tumble.”

During the satellite’s first week in space, Varda will focus on testing its systems to make sure everything works as hoped. The second week will be dedicated to heating and cooling the old HIV-AIDS drug ritonavir repeatedly to study how its particles crystalize in microgravity.

After about a month in space, Varda will attempt to bring its first space factory back to Earth, sending it through the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds and then using a parachute system to safely land at the Department of Defense’s Utah Test and Training Range.

Looking ahead: Ultimately, Varda’s space factories could end up serving dual purposes as manufacturing facilities and hypersonic testbeds — the Air Force has already awarded the startup a contract to use its next reentry capsule to test hardware for hypersonic missiles.

But as for manufacturing other types of goods, Varda plans to stick with drugs for now.

“[Pharmaceuticals] are the most valuable chemicals per unit mass,” Bruey told CNN. “And they also have a large market on Earth.”

“You’re not going to see Varda do anything other than pharmaceuticals for the next minimum of six, seven years,” added Delian Asparouhov, Varda’s co-founder and president.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Genes that protect health with Dr. Nir Barzilai

Centenarians essentially won the genetic lottery, says Nir Barzilai of Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He is studying their genes to see how the rest of us can benefit from understanding how they work.

In today’s podcast episode, I talk with Nir Barzilai, a geroscientist, which means he studies the biology of aging. Barzilai directs the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

My first question for Dr. Barzilai was: why do we age? And is there anything to be done about it? His answers were encouraging. We can’t live forever, but we have some control over the process, as he argues in his book, Age Later.

Dr. Barzilai told me that centenarians differ from the rest of us because they have unique gene mutations that help them stay healthy longer. For most of us, the words “gene mutations” spell trouble - we associate these words with cancer or neurodegenerative diseases, but apparently not all mutations are bad.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Centenarians may have essentially won the genetic lottery, but that doesn’t mean the rest of us are predestined to have a specific lifespan and health span, or the amount of time spent living productively and enjoyably. “Aging is a mother of all diseases,” Dr. Barzilai told me. And as a disease, it can be targeted by therapeutics. Dr. Barzilai’s team is already running clinical trials on such therapeutics — and the results are promising.

More about Dr. Barzilai: He is scientific director of AFAR, American Federation for Aging Research. As part of his work, Dr. Barzilai studies families of centenarians and their genetics to learn how the rest of us can learn and benefit from their super-aging. He also organizing a clinical trial to test a specific drug that may slow aging.

Show Links

Age Later: Health Span, Life Span, and the New Science of Longevity https://www.amazon.com/Age-Later-Healthiest-Sharpest-Centenarians/dp/1250230853

American Federation for Aging Research https://www.afar.org

https://www.afar.org/nir-barzilai

https://www.einsteinmed.edu/faculty/484/nir-barzilai/

Metformin as a Tool to Target Aging

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5943638/

Benefits of Metformin in Attenuating the Hallmarks of Aging https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7347426/

The Longevity Genes Project https://www.einsteinmed.edu/centers/aging/longevity-genes-project/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.