What to Know about the Fast-Spreading Delta Variant

A highly contagious form of the coronavirus known as the Delta variant is spreading rapidly and becoming increasingly prevalent around the world. First identified in India in December, Delta has now been identified in 111 countries.

In the United States, the variant now accounts for 83% of sequenced COVID-19 cases, said Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at a July 20 Senate hearing. In May, Delta was responsible for just 3% of U.S. cases. The World Health Organization projects that Delta will become the dominant variant globally over the coming months.

So, how worried should you be about the Delta variant? We asked experts some common questions about Delta.

What is a variant?

To understand Delta, it's helpful to first understand what a variant is. When a virus infects a person, it gets into your cells and makes a copy of its genome so it can replicate and spread throughout your body.

In the process of making new copies of itself, the virus can make a mistake in its genetic code. Because viruses are replicating all the time, these mistakes — also called mutations — happen pretty often. A new variant emerges when a virus acquires one or more new mutations and starts spreading within a population.

There are thousands of SARS-CoV-2 variants, but most of them don't substantially change the way the virus behaves. The variants that scientists are most interested in are known as variants of concern. These are versions of the virus with mutations that allow the virus to spread more easily, evade vaccines, or cause more severe disease.

"The vast majority of the mutations that have accumulated in SARS-CoV-2 don't change the biology as far as we're concerned," said Jennifer Surtees, a biochemist at the University of Buffalo who's studying the coronavirus. "But there have been a handful of key mutations and combinations of mutations that have led to what we're now calling variants of concern."

One of those variants of concern is Delta, which is now driving many new COVID-19 infections.

Why is the Delta variant so concerning?

"The reason why the Delta variant is concerning is because it's causing an increase in transmission," said Alba Grifoni, an infectious disease researcher at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. "The virus is spreading faster and people — particularly those who are not vaccinated yet — are more prone to exposure."

The Delta variant has a few key mutations that make it better at attaching to our cells and evading the neutralizing antibodies in our immune system. These mutations have changed the virus enough to make it more than twice as contagious as the original SARS-CoV-2 virus that emerged in Wuhan and about 50% more contagious than the Alpha variant, previously known as B.1.1.7, or the U.K. variant.

These mutations were previously seen in other variants on their own, but it's their combination that makes Delta so much more infectious.

Do vaccines work against the Delta variant?

The good news is, the COVID-19 vaccines made by AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer still work against the Delta variant. They remain more than 90% effective at preventing hospitalizations and death due to Delta. While they're slightly less protective against disease symptoms, they're still very effective at preventing severe illness caused by the Delta variant.

"They're not as good as they were against the prior strains, but they're holding up pretty well," said Eric Topol, a physician and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute, during a July 19 briefing for journalists.

Because Delta is better at evading our immune systems, it's likely causing more breakthrough infections — COVID-19 cases in people who are vaccinated. However, breakthrough infections were expected before the Delta variant became widespread. No vaccine is 100% effective, so breakthrough infections can happen with other vaccines as well. Experts say the COVID-19 vaccines are still working as expected, even if breakthrough infections occur. The majority of these infections are asymptomatic or cause only mild symptoms.

Should vaccinated people worry about the Delta variant?

Vaccines train our immune systems to protect us against infection. They do this by spurring the production of antibodies, which stick around in our bodies to help fight off a particular pathogen in case we ever come into contact with it.

But even if the new Delta variant slips past our neutralizing antibodies, there's another component of our immune system that can help overtake the virus: T cells. Studies are showing that the COVID-19 vaccines also galvanize T cells, which help limit disease severity in people who have been vaccinated.

"While antibodies block the virus and prevent the virus from infecting cells, T cells are able to attack cells that have already been infected," Grifoni said. In other words, T cells can prevent the infection from spreading to more places in the body. A study published July 1 by Grifoni and her colleagues found that T cells were still able to recognize mutated forms of the virus — further evidence that our current vaccines are effective against Delta.

Can fully vaccinated people spread the Delta variant?

Previously, scientists believed it was unlikely for fully vaccinated individuals with asymptomatic infections to spread Covid-19. But the Delta variant causes the virus to make so many more copies of itself inside the body, and high viral loads have been found in the respiratory tracts of people who are fully vaccinated. This suggests that vaccinated people may be able to spread the Delta variant to some degree.

If you have COVID-19 symptoms, even if you're fully vaccinated, you should get tested and isolate from friends and family because you could spread the virus.

What risk does Delta pose to unvaccinated people?

The Delta variant is behind a surge in cases in communities with low vaccination rates, and unvaccinated Americans currently account for 97% of hospitalizations due to COVID-19, according to Walensky. The best thing you can do right now to prevent yourself from getting sick is to get vaccinated.

Gigi Gronvall, an immunologist and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, said in this week's "Making Sense of Science" podcast that it's especially important to get all required doses of the vaccine in order to have the best protection against the Delta variant. "Even if it's been more than the allotted time that you were told to come back and get the second, there's no time like the present," she said.

With more than 3.6 billion COVID-19 doses administered globally, the vaccines have been shown to be incredibly safe. Serious adverse effects are rare, although scientists continue to monitor for them.

Being vaccinated also helps prevent the emergence of new and potentially more dangerous variants. Viruses need to infect people in order to replicate, and variants emerge because the virus continues to infect more people. More infections create more opportunities for the virus to acquire new mutations.

Surtees and others worry about a scenario in which a new variant emerges that's even more transmissible or resistant to vaccines. "This is our window of opportunity to try to get as many people vaccinated as possible and get people protected so that so that the virus doesn't evolve to be even better at infecting people," she said.

Does Delta cause more severe disease?

While hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are increasing again, it's not yet clear whether Delta causes more severe illness than previous strains.

How can we protect unvaccinated children from the Delta variant?

With children 12 and under not yet eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine, kids are especially vulnerable to the Delta variant. One way to protect unvaccinated children is for parents and other close family members to get vaccinated.

It's also a good idea to keep masks handy when going out in public places. Due to risk Delta poses, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued new guidelines July 19 recommending that all staff and students over age 2 wear face masks in school this fall, even if they have been vaccinated.

Parents should also avoid taking their unvaccinated children to crowded, indoor locations and make sure their kids are practicing good hand-washing hygiene. For children younger than 2, limit visits with friends and family members who are unvaccinated or whose vaccination status is unknown and keep up social distancing practices while in public.

While there's no evidence yet that Delta increases disease severity in children, parents should be mindful that in some rare cases, kids can get a severe form of the disease.

"We're seeing more children getting sick and we're seeing some of them get very sick," Surtees said. "Those children can then pass on the virus to other individuals, including people who are immunocompromised or unvaccinated."

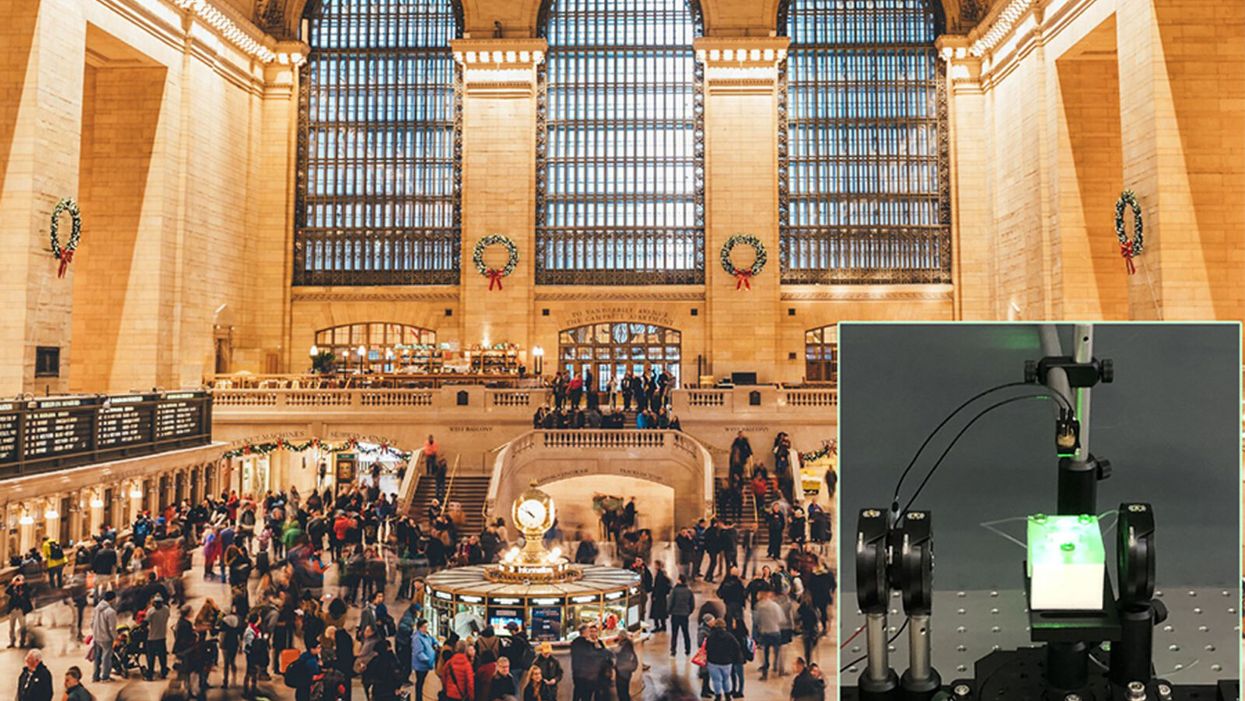

A biosensor in development (inset) could potentially be used to detect novel viruses in transit hubs like Grand Central Station in New York City.

The unprecedented scale and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused scientists and engineers around the world to stop whatever they were working on and shift their research toward understanding a novel virus instead.

"We have confidence that we can use our system in the next pandemic."

For Guangyu Qiu, normally an environmental engineer at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, that means finding a clever way to take his work on detecting pollution in the air and apply it to living pathogens instead. He's developing a new type of biosensor to make disease diagnostics and detection faster and more accurate than what's currently available.

But even though this pandemic was the impetus for designing a new biosensor, Qiu actually has his eye on future disease outbreaks. He admits that it's unlikely his device will play a role in quelling this virus, but says researchers already need to be thinking about how to make better tools to fight the next one — because there will be a next one.

"In the last 20 years, there [have been] three different coronavirus [outbreaks] ... so we have to prepare for the coming one," Qiu says. "We have confidence that we can use our system in the next pandemic."

"A Really, Really Neat Idea"

His main concern is the diagnostic tool that's currently front and center for testing patients for SARS-Cov-2, the virus causing the novel coronavirus disease. The tool, called PCR (short for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction), is the gold standard because it excels at detecting viruses in even very small samples of mucus. PCR can amplify genetic material in the limited sample and look for a genetic code matching the virus in question. But in many parts of the world, mucus samples have to be sent out to laboratories for that work, and results can take days to return. PCR is also notoriously prone to false positives and negatives.

"I read a lot of newspapers that report[ed] ... a lot of false negative or false positive results at the very beginning of the outbreak," Qiu says. "It's not good for protecting people to prevent further transmission of the disease."

So he set out to build a more sensitive device—one that's less likely to give you a false result. Qiu's biosensor relies on an idea similar to the dual-factor authentication required of anyone trying to access a secure webpage. Instead of verifying that a virus is really present by using one way of detecting genetic code, as with PCR, this biosensor asks for two forms of ID.

SARS-CoV-2 is what's called an RNA virus, which means it has a single strand of genetic code, unlike double-stranded DNA. Inside Qiu's biosensor are receptors with the complementary code for this particular virus' RNA; if the virus is present, its RNA will bind with the receptors, locking together like velcro. The biosensor also contains a prism and a laser that work together to verify that this RNA really belongs to SARS-CoV-2 by looking for a specific wavelength of light and temperature.

If the biosensor doesn't detect either, or only registers a match for one and not the other, then it can't produce a positive result. This multi-step authentication process helps make sure that the RNA binding with the receptors isn't a genetically similar coronavirus like SARS-CoV, known for its 2003 outbreak, or MERS-CoV, which caused an epidemic in 2012.

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The dual-feature design of this biosensor "is a really, really neat idea that I have not seen before with other sensor technology," says Erin Bromage, a professor of infection and immunology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth; he was not involved in designing or testing Qiu's biosensor. "It makes you feel more secure that when you have a positive, you've really got a positive."

The light and temperature sensors are not in themselves new inventions, but the combination is a first. The part of the device that uses light to detect particles is actually central to Qiu's normal stream of environmental research, and is a versatile tool he's been working with for a long time to detect aerosols in the atmosphere and heavy metals in drinking water.

Bromage says this is a plus. "It's not high-risk in the sense that how they do this is unique, or not validated. They've taken aspects of really proven technology and sort of combined it together."

This new biosensor is still a prototype that will take at least another 12 months to validate in real world scenarios, though. The device is sound from a biological perspective and is sensitive enough to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 — and to not be tricked by genetically similar viruses like SARS-CoV — but there is still a lot of engineering work that needs to be done in order for it to work outside the lab. Qiu says it's unlikely that the sensor will help minimize the impact of this pandemic, but the RNA receptors, prism, and laser inside the device can be customized to detect other viruses that may crop up in the future.

"If we choose another sequence—like SARS, like MERS, or like normal seasonal flu—we can detect other viruses, or even bacteria," Qiu says. "This device is very flexible."

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The Long-Term Vision: Hospitals and Transit Hubs

The device has been designed to connect with two other systems: an air sampler and a microprocessor because the goal is to make it portable, and able to pick up samples from the air in hospitals or public areas like train stations or airports. A virus could hopefully be detected before it silently spreads and erupts into another global pandemic. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been conflicting research about whether or not the virus is truly airborne (though it can be spread by droplets that briefly move through the air after a cough or sneeze), whereas the highly contagious RNA virus that causes measles can remain in the air for up to two hours.

"They've got a lot on the front end to work out," Bromage says. "They've got to work out how to capture and concentrate a virus, extract the RNA from the virus, and then get it onto the sensor. That's some pretty big hurdles, and may take some engineering that doesn't exist right now. But, if they can do that, then that works out really quite well."

One of the major obstacles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic has been in deploying accurate, quick tools that can be used for early detection of a virus outbreak and for later tracing its spread. That will still be true the next time a novel virus rears its head, and it's why Qiu feels that even if his biosensor can't help just yet, the research is still worth the effort.

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The dual-feature design of this biosensor "is a really, really neat idea that I have not seen before with other sensor technology," says Erin Bromage, a professor of infection and immunology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth; he was not involved in designing or testing Qiu's biosensor. "It makes you feel more secure that when you have a positive, you've really got a positive."

The light and temperature sensors are not in themselves new inventions, but the combination is a first. The part of the device that uses light to detect particles is actually central to Qiu's normal stream of environmental research, and is a versatile tool he's been working with for a long time to detect aerosols in the atmosphere and heavy metals in drinking water.

Bromage says this is a plus. "It's not high-risk in the sense that how they do this is unique, or not validated. They've taken aspects of really proven technology and sort of combined it together."

This new biosensor is still a prototype that will take at least another 12 months to validate in real world scenarios, though. The device is sound from a biological perspective and is sensitive enough to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 — and to not be tricked by genetically similar viruses like SARS-CoV — but there is still a lot of engineering work that needs to be done in order for it to work outside the lab. Qiu says it's unlikely that the sensor will help minimize the impact of this pandemic, but the RNA receptors, prism, and laser inside the device can be customized to detect other viruses that may crop up in the future.

"If we choose another sequence—like SARS, like MERS, or like normal seasonal flu—we can detect other viruses, or even bacteria," Qiu says. "This device is very flexible."

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The Long-Term Vision: Hospitals and Transit Hubs

The device has been designed to connect with two other systems: an air sampler and a microprocessor because the goal is to make it portable, and able to pick up samples from the air in hospitals or public areas like train stations or airports. A virus could hopefully be detected before it silently spreads and erupts into another global pandemic. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been conflicting research about whether or not the virus is truly airborne (though it can be spread by droplets that briefly move through the air after a cough or sneeze), whereas the highly contagious RNA virus that causes measles can remain in the air for up to two hours.

"They've got a lot on the front end to work out," Bromage says. "They've got to work out how to capture and concentrate a virus, extract the RNA from the virus, and then get it onto the sensor. That's some pretty big hurdles, and may take some engineering that doesn't exist right now. But, if they can do that, then that works out really quite well."

One of the major obstacles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic has been in deploying accurate, quick tools that can be used for early detection of a virus outbreak and for later tracing its spread. That will still be true the next time a novel virus rears its head, and it's why Qiu feels that even if his biosensor can't help just yet, the research is still worth the effort.

Spina Bifida Claimed My Son's Mobility. Incredible Breakthroughs May Let Future Kids Run Free.

Sarah Watts's son Henry was born with spina bifida and can't stand or walk without assistance.

When our son Henry, now six, was diagnosed with spina bifida at his 20-week ultrasound, my husband and I were in shock. It took us more than a few minutes to understand what the doctor was telling us.

When Henry was diagnosed in 2012, postnatal surgery was still the standard of care – but that was about to change.

Neither of us had any family history of birth defects. Our fifteen-month-old daughter, June, was in perfect health.

But more than that, spina bifida – a malformation of the neural tube that eventually becomes the baby's spine – is woefully complex. The defect, the doctor explained, was essentially a hole in Henry's lower spine from which his spinal nerves were protruding – and because they were exposed to my amniotic fluid, those nerves were already permanently damaged. After birth, doctors could push the nerves back into his body and sew up the hole, but he would likely experience some level of paralysis, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid that would require a surgical implant called a shunt to correct. The damage was devastating – and irreversible.

We returned home with June and spent the next few days cycling between disbelief and total despair. But within a week, the maternal-fetal medicine specialist who diagnosed Henry called us up and gave us the first real optimism we had felt in days: There was a new, experimental surgery for spina bifida that was available in just a handful of hospitals around the country. Rather than waiting until birth to repair the baby's defect, some doctors were now trying out a prenatal repair, operating on the baby via c-section, closing the defect, and then keeping the mother on strict bedrest until it was time for the baby to be delivered, just before term.

This new surgery carried risks, he told us – but if it went well, there was a chance Henry wouldn't need a shunt. And because repairing the defect during my pregnancy meant the spinal nerves were exposed for a shorter amount of time, that meant we'd be preventing nerve damage – and less nerve damage meant that there was a chance he'd be able to walk.

Did we want in? the doctor asked.

Had I known more about spina bifida and the history of its treatment, this surgery would have seemed even more miraculous. Not too long ago, the standard of care for babies born with spina bifida was to simply let them die without medical treatment. In fact, it wasn't until the early 1950s that doctors even attempted to surgically repair the baby's defect at all, instead of opting to let the more severe cases die of meningitis from their open wound. (Babies who had closed spina bifida – a spinal defect covered by skin – sometimes survived past infancy, but rarely into adulthood).

But in the 1960s and 1970s, as more doctors started repairing defects and the shunting technology improved, patients with spina bifida began to survive past infancy. When catheterization was introduced, spina bifida patients who had urinary dysfunction, as is common, were able to preserve their renal function into adulthood, and they began living even longer. Within a few decades, spina bifida was no longer considered a death sentence; people were living fuller, happier lives.

When Henry was diagnosed in 2012, postnatal surgery was still the standard of care – but that was about to change. The first major clinical trial for prenatal surgery and spina bifida, called Management of Myelomeningocele (MOMS) had just concluded, and its objective was to see whether repairing the baby's defect in utero would be beneficial. In the trial, doctors assigned eligible women to undergo prenatal surgery in the second trimester of their pregnancies and then followed up with their children throughout the first 30 months of the child's life.

The results were groundbreaking: Not only did the children in the surgery group perform better on motor skills and cognitive tests than did patients in the control group, only 40 percent of patients ended up needing shunts compared to 80 percent of patients who had postnatal surgery. The results were so overwhelmingly positive that the trial was discontinued early (and is now, happily, the medical standard of care). Our doctor relayed this information to us over the phone, breathless, and left my husband and me to make our decision.

After a few days of consideration, and despite the benefits, my husband and I actually ended up opting for the postnatal surgery instead. Prenatal surgery, although miraculous, would have required extensive travel for us, as well as giving birth in a city thousands of miles from home with no one to watch our toddler while my husband worked and I recovered. But other parents I met online throughout our pregnancy did end up choosing prenatal surgery for their children – and the majority of them now walk with little assistance and only a few require shunting.

Even more amazing to me is that now – seven years after Henry's diagnosis, and not quite a decade since the landmark MOMS trial – the standard of care could be about to change yet again.

Regardless of whether they have postnatal or prenatal surgery, most kids with spina bifida still experience some level of paralysis and rely on wheelchairs and walkers to move around. Now, researchers at UC Davis want to augment the fetal surgery with a stem cell treatment, using human placenta-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (PMSCs) and affixing them to a cellular scaffold on the baby's defect, which not only protects the spinal cord from further damage but actually encourages cellular regeneration as well.

The hope is that this treatment will restore gross motor function after the baby is born – and so far, in animal trials, that's exactly what's happening. Fetal sheep, who were induced with spinal cord injuries in utero, were born with complete motor function after receiving prenatal surgery and PMSCs. In 2017, a pair of bulldogs born with spina bifida received the stem cell treatment a few weeks after birth – and two months after surgery, both dogs could run and play freely, whereas before they had dragged their hind legs on the ground behind them. UC Davis researchers hope to bring this treatment into human clinical trials within the next year.

A century ago, a diagnosis of spina bifida meant almost certain death. Today, most children with spina bifida live into adulthood, albeit with significant disabilities. But thanks to research and innovation, it's entirely possible that within my lifetime – and certainly within Henry's – for the first time in human history, the disabilities associated with spina bifida could be a thing of the past.