What’s the Right Way to Regulate Gene-Edited Crops?

A cornfield in summer.

In the next few decades, humanity faces its biggest food crisis since the invention of the plow. The planet's population, currently 7.6 billion, is expected to reach 10 billion by 2050; to avoid mass famine, according to the World Resource Institute, we'll need to produce 70 percent more calories than we do today.

Imagine that a cheap, easy-to-use, and rapidly deployable technology could make crops more fertile and strengthen their resistance to threats.

Meanwhile, climate change will bring intensifying assaults by heat, drought, storms, pests, and weeds, depressing farm yields around the globe. Epidemics of plant disease—already laying waste to wheat, citrus, bananas, coffee, and cacao in many regions—will spread ever further through the vectors of modern trade and transportation.

So here's a thought experiment: Imagine that a cheap, easy-to-use, and rapidly deployable technology could make crops more fertile and strengthen their resistance to these looming threats. Imagine that it could also render them more nutritious and tastier, with longer shelf lives and less vulnerability to damage in shipping—adding enhancements to human health and enjoyment, as well as reduced food waste, to the possible benefits.

Finally, imagine that crops bred with the aid of this tool might carry dangers. Some could contain unsuspected allergens or toxins. Others might disrupt ecosystems, affecting the behavior or very survival of other species, or infecting wild relatives with their altered DNA.

Now ask yourself: If such a technology existed, should policymakers encourage its adoption, or ban it due to the risks? And if you chose the former alternative, how should crops developed by this method be regulated?

In fact, this technology does exist, though its use remains mostly experimental. It's called gene editing, and in the past five years it has emerged as a potentially revolutionary force in many areas—among them, treating cancer and genetic disorders; growing transplantable human organs in pigs; controlling malaria-spreading mosquitoes; and, yes, transforming agriculture. Several versions are currently available, the newest and nimblest of which goes by the acronym CRISPR.

Gene editing is far simpler and more efficient than older methods used to produce genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Unlike those methods, moreover, it can be used in ways that leave no foreign genes in the target organism—an advantage that proponents argue should comfort anyone leery of consuming so-called "Frankenfoods." But debate persists over what precautions must be taken before these crops come to market.

Recently, two of the world's most powerful regulatory bodies offered very different answers to that question. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) declared in March 2018 that it "does not currently regulate, or have any plans to regulate" plants that are developed through most existing methods of gene editing. The Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ), by contrast, ruled in July that such crops should be governed by the same stringent regulations as conventional GMOs.

Some experts suggest that the broadly permissive American approach and the broadly restrictive EU policy are equally flawed.

Each announcement drew protests, for opposite reasons. Anti-GMO activists assailed the USDA's statement, arguing that all gene-edited crops should be tested and approved before marketing. "You don't know what those mutations or rearrangements might do in a plant," warned Michael Hansen, a senior scientist with the advocacy group Consumers Union. Biotech boosters griped that the ECJ's decision would stifle innovation and investment. "By any sensible standard, this judgment is illogical and absurd," wrote the British newspaper The Observer.

Yet some experts suggest that the broadly permissive American approach and the broadly restrictive EU policy are equally flawed. "What's behind these regulatory decisions is not science," says Jennifer Kuzma, co-director of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center at North Carolina State University, a former advisor to the World Economic Forum, who has researched and written extensively on governance issues in biotechnology. "It's politics, economics, and culture."

The U.S. Welcomes Gene-Edited Food

Humans have been modifying the genomes of plants and animals for 10,000 years, using selective breeding—a hit-or-miss method that can take decades or more to deliver rewards. In the mid-20th century, we learned to speed up the process by exposing organisms to radiation or mutagenic chemicals. But it wasn't until the 1980s that scientists began modifying plants by altering specific stretches of their DNA.

Today, about 90 percent of the corn, cotton and soybeans planted in the U.S. are GMOs; such crops cover nearly 4 million square miles (10 million square kilometers) of land in 29 countries. Most of these plants are transgenic, meaning they contain genes from an unrelated species—often as biologically alien as a virus or a fish. Their modifications are designed primarily to boost profit margins for mechanized agribusiness: allowing crops to withstand herbicides so that weeds can be controlled by mass spraying, for example, or to produce their own pesticides to lessen the need for chemical inputs.

In the early days, the majority of GM crops were created by extracting the gene for a desired trait from a donor organism, multiplying it, and attaching it to other snippets of DNA—usually from a microbe called an agrobacterium—that could help it infiltrate the cells of the target plant. Biotechnologists injected these particles into the target, hoping at least one would land in a place where it would perform its intended function; if not, they kept trying. The process was quicker than conventional breeding, but still complex, scattershot, and costly.

Because agrobacteria can cause plant tumors, Kuzma explains, policymakers in the U.S. decided to regulate GMO crops under an existing law, the Plant Pest Act of 1957, which addressed dangers like imported trees infested with invasive bugs. Every GMO containing the DNA of agrobacterium or another plant pest had to be tested to see whether it behaved like a pest, and undergo a lengthy approval process. By 2010, however, new methods had been developed for creating GMOs without agrobacteria; such plants could typically be marketed without pre-approval.

Soon after that, the first gene-edited crops began appearing. If old-school genetic engineering was a shotgun, techniques like TALEN and CRISPR were a scalpel—or the search-and-replace function on a computer program. With CRISPR/Cas9, for example, an enzyme that bacteria use to recognize and chop up hostile viruses is reprogrammed to find and snip out a desired bit of a plant or other organism's DNA. The enzyme can also be used to insert a substitute gene. If a DNA sequence is simply removed, or the new gene comes from a similar species, the changes in the target plant's genotype and phenotype (its general characteristics) may be no different from those that could be produced through selective breeding. If a foreign gene is added, the plant becomes a transgenic GMO.

Companies are already teeing up gene-edited products for the U.S. market, like a cooking oil and waxy corn.

This development, along with the emergence of non-agrobacterium GMOs, eventually prompted the USDA to propose a tiered regulatory system for all genetically engineered crops, beginning with an initial screening for potentially hazardous metaboloids or ecological impacts. (The screening was intended, in part, to guard against the "off-target effects"—stray mutations—that occasionally appear in gene-edited organisms.) If no red flags appeared, the crop would be approved; otherwise, it would be subject to further review, and possible regulation.

The plan was unveiled in January 2017, during the last week of the Obama presidency. Then, under the Trump administration, it was shelved. Although the USDA continues to promise a new set of regulations, the only hint of what they might contain has been Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue's statement last March that gene-edited plants would remain unregulated if they "could otherwise have been developed through traditional breeding techniques, as long as they are not plant pests or developed using plant pests."

Because transgenic plants could not be "developed through traditional breeding techniques," this statement could be taken to mean that gene editing in which foreign DNA is introduced might actually be regulated. But because the USDA regulates conventional transgenic GMOs only if they trigger the plant-pest stipulation, experts assume gene-edited crops will face similarly limited oversight.

Meanwhile, companies are already teeing up gene-edited products for the U.S. market. An herbicide-resistant oilseed rape, developed using a proprietary technique, has been available since 2016. A cooking oil made from TALEN-tweaked soybeans, designed to have a healthier fatty-acid profile, is slated for release within the next few months. A CRISPR-edited "waxy" corn, designed with a starch profile ideal for processed foods, should be ready by 2021.

In all likelihood, none of these products will have to be tested for safety.

In the E.U., Stricter Rules Apply

Now let's look at the European Union. Since the late 1990s, explains Gregory Jaffe, director of the Project on Biotechnology at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the EU has had a "process-based trigger" for genetically engineered products: "If you use recombinant DNA, you are going to be regulated." All foods and animal feeds must be approved and labeled if they consist of or contain more than 0.9 percent GM ingredients. (In the U.S., "disclosure" of GM ingredients is mandatory, if someone asks, but labeling is not required.) The only GM crop that can be commercially grown in EU member nations is a type of insect-resistant corn, though some countries allow imports.

European scientists helped develop gene editing, and they—along with the continent's biotech entrepreneurs—have been busy developing applications for crops. But European farmers seem more divided over the technology than their American counterparts. The main French agricultural trades union, for example, supports research into non-transgenic gene editing and its exemption from GMO regulation. But it was the country's small-farmers' union, the Confédération Paysanne, along with several allied groups, that in 2015 submitted a complaint to the ECJ, asking that all plants produced via mutagenesis—including gene-editing—be regulated as GMOs.

At this point, it should be mentioned that in the past 30 years, large population studies have found no sign that consuming GM foods is harmful to human health. GMO critics can, however, point to evidence that herbicide-resistant crops have encouraged overuse of herbicides, giving rise to poison-proof "superweeds," polluting the environment with suspected carcinogens, and inadvertently killing beneficial plants. Those allegations were key to the French plaintiffs' argument that gene-edited crops might similarly do unexpected harm. (Disclosure: Leapsmag's parent company, Bayer, recently acquired Monsanto, a maker of herbicides and herbicide-resistant seeds. Also, Leaps by Bayer, an innovation initiative of Bayer and Leapsmag's direct founder, has funded a biotech startup called JoynBio that aims to reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer required to grow crops.)

The ruling was "scientifically nonsensical. It's because of things like this that I'll never go back to Europe."

In the end, the EU court found in the Confédération's favor on gene editing—though the court maintained the regulatory exemption for mutagenesis induced by chemicals or radiation, citing the 'long safety record' of those methods.

The ruling was "scientifically nonsensical," fumes Rodolphe Barrangou, a French food scientist who pioneered CRISPR while working for DuPont in Wisconsin and is now a professor at NC State. "It's because of things like this that I'll never go back to Europe."

Nonetheless, the decision was consistent with longstanding EU policy on crops made with recombinant DNA. Given the difficulty and expense of getting such products through the continent's regulatory system, many other European researchers may wind up following Barrangou to America.

Getting to the Root of the Cultural Divide

What explains the divergence between the American and European approaches to GMOs—and, by extension, gene-edited crops? In part, Jennifer Kuzma speculates, it's that Europeans have a different attitude toward eating. "They're generally more tied to where their food comes from, where it's produced," she notes. They may also share a mistrust of government assurances on food safety, borne of the region's Mad Cow scandals of the 1980s and '90s. In Catholic countries, consumers may have misgivings about tinkering with the machinery of life.

But the principal factor, Kuzma argues, is that European and American agriculture are structured differently. "GM's benefits have mostly been designed for large-scale industrial farming and commodity crops," she says. That kind of farming is dominant in the U.S., but not in Europe, leading to a different balance of political power. In the EU, there was less pressure on decisionmakers to approve GMOs or exempt gene-edited crops from regulation—and more pressure to adopt a GM-resistant stance.

Such dynamics may be operating in other regions as well. In China, for example, the government has long encouraged research in GMOs; a state-owned company recently acquired Syngenta, a Swiss-based multinational corporation that is a leading developer of GM and gene-edited crops. GM animal feed and cooking oil can be freely imported. Yet commercial cultivation of most GM plants remains forbidden, out of deference to popular suspicions of genetically altered food. "As a new item, society has debates and doubts on GMO techniques, which is normal," President Xi Jinping remarked in 2014. "We must be bold in studying it, [but] be cautious promoting it."

The proper balance between boldness and caution is still being worked out all over the world. Europe's process-based approach may prevent researchers from developing crops that, with a single DNA snip, could rescue millions from starvation. EU regulations will also make it harder for small entrepreneurs to challenge Big Ag with a technology that, as Barrangou puts it, "can be used affordably, quickly, scalably, by anyone, without even a graduate degree in genetics." America's product-based approach, conversely, may let crops with hidden genetic dangers escape detection. And by refusing to investigate such risks, regulators may wind up exacerbating consumers' doubts about GM and gene-edited products, rather than allaying them.

"Science...can't tell you what to regulate. That's a values-based decision."

Perhaps the solution lies in combining both approaches, and adding some flexibility and nuance to the mix. "I don't believe in regulation by the product or the process," says CSPI's Jaffe. "I think you need both." Deleting a DNA base pair to silence a gene, for example, might be less risky than inserting a foreign gene into a plant—unless the deletion enables the production of an allergen, and the transgene comes from spinach.

Kuzma calls for the creation of "cooperative governance networks" to oversee crop genome editing, similar to bodies that already help develop and enforce industry standards in fisheries, electronics, industrial cleaning products, and (not incidentally) organic agriculture. Such a network could include farmers, scientists, advocacy groups, private companies, and governmental agencies. "Safety isn't an all-or-nothing concept," Kuzma says. "Science can tell you what some of the issues are in terms of risk and benefit, but it can't tell you what to regulate. That's a values-based decision."

By drawing together a wide range of stakeholders to make such decisions, she adds, "we're more likely to anticipate future consequences, and to develop a robust approach—one that not only seems more legitimate to people, but is actually just plain old better."

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

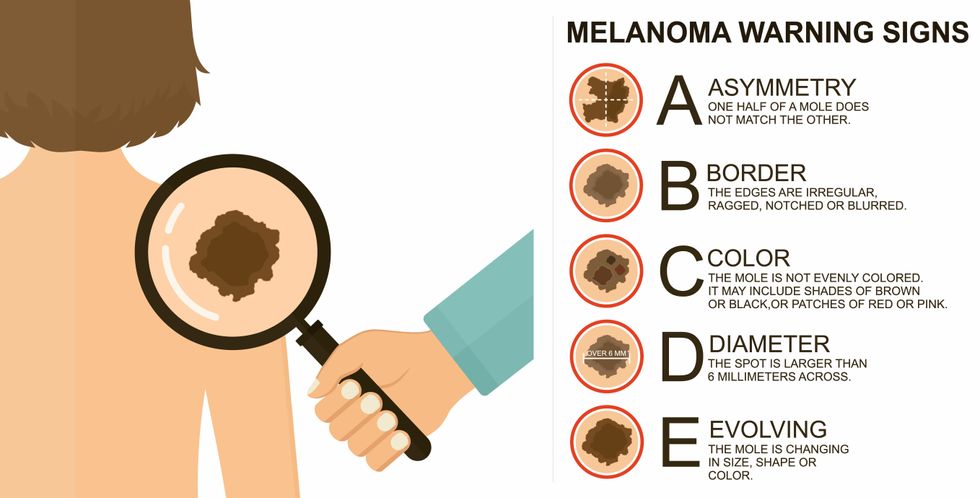

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.