Who Qualifies as an “Expert” And How Can We Decide Who Is Trustworthy?

Discerning a real expert from a charlatan is crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

Expertise is a slippery concept. Who has it, who claims it, and who attributes or yields it to whom is a culturally specific, sociological process. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed a remarkable emergence of legitimate and not-so-legitimate scientists publicly claiming or being attributed to have academic expertise in precisely my field: infectious disease epidemiology. From any vantage point, it is clear that charlatans abound out there, garnering TV coverage and hundreds of thousands of Twitter followers based on loud opinions despite flimsy credentials. What is more interesting as an insider is the gradient of expertise beyond these obvious fakers.

A person's expertise is not a fixed attribute; it is a hierarchical trait defined relative to others. Despite my protestations, I am the go-to expert on every aspect of the pandemic to my family. To a reporter, I might do my best to answer a question about the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, noting that I'm not an immunologist. Among other academic scientists, my expertise is more well-defined as a subfield of epidemiology, and within that as a particular area within infectious disease epidemiology. There's a fractal quality to it; as you zoom in on a particular subject, a differentiation of expertise emerges among scientists who, from farther out, appear to be interchangeable.

We all have our scientific domain and are less knowledgeable outside it, of course, and we are often asked to comment on a broad range of topics. But many scientists without a track record in the field have become favorites among university administrators, senior faculty in unrelated fields, policymakers, and science journalists, using institutional prestige or social connections to promote themselves. This phenomenon leads to a distorted representation of science—and of academic scientists—in the public realm.

Trustworthy experts will direct you to others in their field who know more about particular topics, and will tend to be honest about what is and what isn't "in their lane."

Predictably, white male voices have been disproportionately amplified, and men are certainly over-represented in the category of those who use their connections to inappropriately claim expertise. Generally speaking, we are missing women, racial minorities, and global perspectives. This is not only important because it misrepresents who scientists are and reinforces outdated stereotypes that place white men in the Global North at the top of a credibility hierarchy. It also matters because it can promote bad science, and it passes over scientists who can lend nuance to the scientific discourse and give global perspectives on this quintessentially global crisis.

Also at work, in my opinion, are two biases within academia: the conflation of institutional prestige with individual expertise, and the bizarre hierarchy among scientists that attributes greater credibility to those in quantitative fields like physics. Regardless of mathematical expertise or institutional affiliation, lack of experience working with epidemiological data can lead to over-confidence in the deceptively simple mathematical models that we use to understand epidemics, as well as the inappropriate use of uncertain data to inform them. Prominent and vocal scientists from different quantitative fields have misapplied the methods of infectious disease epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic so far, creating enormous confusion among policymakers and the public. Early forecasts that predicted the epidemic would be over by now, for example, led to a sense that epidemiological models were all unreliable.

Meanwhile, legitimate scientific uncertainties and differences of opinion, as well as fundamentally different epidemic dynamics arising in diverse global contexts and in different demographic groups, appear in the press as an indistinguishable part of this general chaos. This leads many people to question whether the field has anything worthwhile to contribute, and muddies the facts about COVID-19 policies for reducing transmission that most experts agree on, like wearing masks and avoiding large indoor gatherings.

So how do we distinguish an expert from a charlatan? I believe a willingness to say "I don't know" and to openly describe uncertainties, nuances, and limitations of science are all good signs. Thoughtful engagement with questions and new ideas is also an indication of expertise, as opposed to arrogant bluster or a bullish insistence on a particular policy strategy regardless of context (which is almost always an attempt to hide a lack of depth of understanding). Trustworthy experts will direct you to others in their field who know more about particular topics, and will tend to be honest about what is and what isn't "in their lane." For example, some expertise is quite specific to a given subfield: epidemiologists who study non-infectious conditions or nutrition, for example, use different methods from those of infectious disease experts, because they generally don't need to account for the exponential growth that is inherent to a contagion process.

Academic scientists have a specific, technical contribution to make in containing the COVID-19 pandemic and in communicating research findings as they emerge. But the liminal space between scientists and the public is subject to the same undercurrents of sexism, racism, and opportunism that society and the academy have always suffered from. Although none of the proxies for expertise described above are fool-proof, they are at least indicative of integrity and humility—two traits the world is in dire need of at this moment in history.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Announcing "The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue"

This special magazine explores what's at stake for science & policy over the next four years.

As reviewed in The Washington Post, "Tomorrow's challenges in science and politics: Magazine offers in-depth takes on these U.S. issues":

"Is it time for a new way to help make adults more science-literate? What should the next president know about science? Could science help strengthen American democracy? "The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue" has answers. The free, online magazine is packed with interesting takes on how science can serve the common good. And just in time. This year has challenged leaders, researchers and the public with thorny scientific questions, from the coronavirus pandemic to widespread misinformation on scientific issues. The magazine is a collaboration of the Aspen Institute, a think tank that brings together a variety of public figures and private individuals to tackle thorny social issues, the digital science magazine Leapsmag and GOOD, a social impact company. It's packed with 15 in-depth articles about science with a view toward our campaign year."

The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue offers wide-ranging perspectives on challenges and opportunities for science as we elect our next national and local leaders. The fast-striking COVID-19 pandemic and the more slowly moving pandemic of climate change have brought into sharp focus how reliant we will be on science and public policy to work together to rescue us from crisis. Doing so will require cooperation between both political parties, as well as significant public trust in science as a beacon to light the path forward.

In spite of its unfortunate emergence as a flash point between two warring parties, we believe that science is the driving force for universal progress. No endeavor is more noble than the quest to rigorously understand our world and apply that knowledge to further human flourishing. This magazine aspires to promote roadmaps for science as a tool for health, a vehicle for progress, and a unifier of our nation.

This special issue is a collaboration among LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD, with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Rita Allen Foundation.

It is available as a free, beautifully designed digital magazine for both desktop and mobile.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

- SCIENTISTS:

Award-Winning Scientists Offer Advice to the Next President of the United States - PUBLIC OPINION:

National Survey Reveals Americans' Most Important Scientific Priorities - GOVERNMENT:

The Nation's Science and Health Agencies Face a Credibility Crisis: Can Their Reputations Be Restored? - TELEVISION:

To Make Science Engaging, We Need a Sesame Street for Adults - IMMIGRATION:

Immigrant Scientists—and America's Edge—Face a Moment of Truth This Election - RACIAL JUSTICE:

Democratize the White Coat by Honoring Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Science - EDUCATION:

I'm a Black, Genderqueer Medical Student: Here's My Hard-Won Wisdom for Students and Educational Institutions - TECHNOLOGY:

"Deep Fake" Video Technology Is Advancing Faster Than Our Policies Can Keep Up - VOTERS:

Mind the (Vote) Gap: Can We Get More STEM Students to the Polls? - EXPERTS:

Who Qualifies as an "Expert" and How Can We Decide Who Is Trustworthy? - SOCIAL MEDIA:

Why Your Brain Falls for Misinformation—And How to Avoid It - YOUTH:

Youth Climate Activists Expand Their Focus and Collaborate to Get Out the Vote - SUPREME COURT:

Abortions Before Fetal Viability Are Legal: Might Science and a Change on the Supreme Court Undermine That? - NAVAJO NATION:

An Environmental Scientist and an Educator Highlight Navajo Efforts to Balance Tradition with Scientific Priorities - CIVIC SCIENCE:

Want to Strengthen American Democracy? The Science of Collaboration Can Help

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Scientists Envision a Universal Coronavirus Vaccine

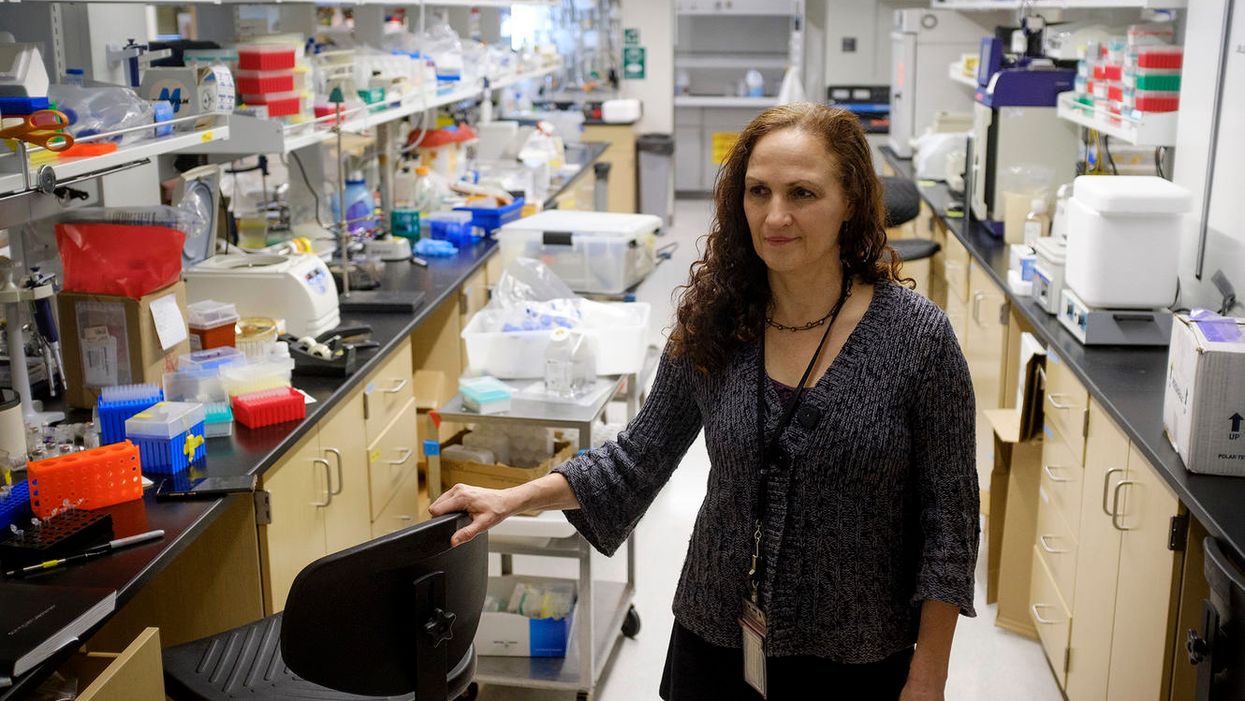

Dr. Deborah Fuller, a professor of microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine, in her lab.

With several companies progressing through Phase III clinical trials, the much-awaited coronavirus vaccines may finally become reality within a few months.

But some scientists question whether these vaccines will produce a strong and long-lasting immunity, especially if they aren't efficient at mobilizing T-cells, the body's defense soldiers.

"When I look at those vaccines there are pitfalls in every one of them," says Deborah Fuller, professor of microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine. "Some may induce only transient antibodies, some may not be very good at inducing T-cell responses, and others may not immunize the elderly very well."

Generally, vaccines work by introducing an antigen into the body—either a dead or attenuated pathogen that can't replicate, or parts of the pathogen or its proteins, which the body will recognize as foreign. The pathogens or its parts are usually discovered by cells that chew up the intruders and present them to the immune system fighters, B- and T-cells—like a trespasser's mug shot to the police. In response, B-cells make antibodies to neutralize the virus, and a specialized "crew" called memory B-cells will remember the antigen. Meanwhile, an army of various T-cells attacks the pathogens as well as the cells these pathogens already infected. Special helper T-cells help stimulate B-cells to secrete antibodies and activate cytotoxic T-cells that release chemicals called inflammatory cytokines that kill pathogens and cells they infected.

"Each of these components of the immune system are important and orchestrated to talk to each other," says professor Larry Corey, who studies vaccines and infectious disease at Fred Hutch, a non-profit scientific research organization. "They optimize the assault of the human immune system on the complexity of the viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic infections that live on our planet, to which we get exposed."

Despite their variety, coronaviruses share certain common proteins and other structural elements, Fuller explains, which the immune system can be trained to identify.

The current frontrunner vaccines aim to train our body to generate a sufficient amount of antibodies to neutralize the virus by shutting off its spike proteins before it enters our cells and begins to replicate. But a truly robust vaccine should also engender a strong response from T-cells, Fuller believes.

"Everyone focuses on the antibodies which block the virus, but it's not always 100 percent effective," she explains. "For example, if there are not enough titers or the antibody starts to wane, and the virus does get into the cells, the cells will become infected. At that point, the body needs to mount a robust T-cytotoxic response. The T-cells should find and recognize cells infected with the virus and eliminate these cells, and the virus with them."

Some of the frontrunner vaccine makers including Moderna, AstraZeneca and CanSino reported that they observed T-cell responses in their trials. Another company, BioNTech, based in Germany, also reported that their vaccine produced T-cell responses.

Fuller and her team are working on their own version of a coronavirus vaccine. In their recent study, the team managed to trigger a strong antibody and T-cell response in mice and primates. Moreover, the aging animals also produced a robust response, which would be important for the human elderly population.

But Fuller's team wants to engage T-cells further. She wants to try training T-cells to recognize not only SARV-CoV-2, but a range of different coronaviruses. Wild hosts, such as bats, carry many different types of coronaviruses, which may spill over onto humans, just like SARS, MERS and SARV-CoV-2 have. There are also four coronaviruses already endemic to humans. Cryptically named 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, they were identified in the 1960s. And while they cause common colds and aren't considered particularly dangerous, the next coronavirus that jumps species may prove deadlier than the previous ones.

Despite their variety, coronaviruses share certain common proteins and other structural elements, Fuller explains, which the immune system can be trained to identify. "T-cells can recognize these shared sequences across multiple different types of coronaviruses," she explains, "so we have this vision for a universal coronavirus vaccine."

Paul Offit at Children's Hospitals in Philadelphia, who specializes in infectious diseases and vaccines, thinks it's a far shot at the moment. "I don't see that as something that is likely to happen, certainly not very soon," he says, adding that a universal flu vaccine has been tried for decades but is not available yet. We still don't know how the current frontrunner vaccines will perform. And until we know how efficient they are, wearing masks and keeping social distance are still important, he notes.

Corey says that while the universal coronavirus vaccine is not impossible, it is certainly not an easy feat. "It is a reasonably scientific hypothesis," he says, but one big challenge is that there are still many unknown coronaviruses so anticipating their structural elements is difficult. The structure of new viruses, particularly the recombinant ones that leap from wild hosts and carry bits and pieces of animal and human genetic material, can be hard to predict. "So whether you can make a vaccine that has universal T-cells to every coronavirus is also difficult to predict," Corey says. But, he adds, "I'm not being negative. I'm just saying that it's a formidable task."

Fuller is certainly up to the task and thinks it's worth the effort. "T-cells can cross-recognize different viruses within the same family," she says, so increasing their abilities to home in on a broader range of coronaviruses would help prevent future pandemics. "If that works, you're just going to take one [vaccine] and you'll have lifetime immunity," she says. "Not just against this coronavirus, but any future pandemic by a coronavirus."

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.