Who Qualifies as an “Expert” And How Can We Decide Who Is Trustworthy?

Discerning a real expert from a charlatan is crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

Expertise is a slippery concept. Who has it, who claims it, and who attributes or yields it to whom is a culturally specific, sociological process. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed a remarkable emergence of legitimate and not-so-legitimate scientists publicly claiming or being attributed to have academic expertise in precisely my field: infectious disease epidemiology. From any vantage point, it is clear that charlatans abound out there, garnering TV coverage and hundreds of thousands of Twitter followers based on loud opinions despite flimsy credentials. What is more interesting as an insider is the gradient of expertise beyond these obvious fakers.

A person's expertise is not a fixed attribute; it is a hierarchical trait defined relative to others. Despite my protestations, I am the go-to expert on every aspect of the pandemic to my family. To a reporter, I might do my best to answer a question about the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, noting that I'm not an immunologist. Among other academic scientists, my expertise is more well-defined as a subfield of epidemiology, and within that as a particular area within infectious disease epidemiology. There's a fractal quality to it; as you zoom in on a particular subject, a differentiation of expertise emerges among scientists who, from farther out, appear to be interchangeable.

We all have our scientific domain and are less knowledgeable outside it, of course, and we are often asked to comment on a broad range of topics. But many scientists without a track record in the field have become favorites among university administrators, senior faculty in unrelated fields, policymakers, and science journalists, using institutional prestige or social connections to promote themselves. This phenomenon leads to a distorted representation of science—and of academic scientists—in the public realm.

Trustworthy experts will direct you to others in their field who know more about particular topics, and will tend to be honest about what is and what isn't "in their lane."

Predictably, white male voices have been disproportionately amplified, and men are certainly over-represented in the category of those who use their connections to inappropriately claim expertise. Generally speaking, we are missing women, racial minorities, and global perspectives. This is not only important because it misrepresents who scientists are and reinforces outdated stereotypes that place white men in the Global North at the top of a credibility hierarchy. It also matters because it can promote bad science, and it passes over scientists who can lend nuance to the scientific discourse and give global perspectives on this quintessentially global crisis.

Also at work, in my opinion, are two biases within academia: the conflation of institutional prestige with individual expertise, and the bizarre hierarchy among scientists that attributes greater credibility to those in quantitative fields like physics. Regardless of mathematical expertise or institutional affiliation, lack of experience working with epidemiological data can lead to over-confidence in the deceptively simple mathematical models that we use to understand epidemics, as well as the inappropriate use of uncertain data to inform them. Prominent and vocal scientists from different quantitative fields have misapplied the methods of infectious disease epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic so far, creating enormous confusion among policymakers and the public. Early forecasts that predicted the epidemic would be over by now, for example, led to a sense that epidemiological models were all unreliable.

Meanwhile, legitimate scientific uncertainties and differences of opinion, as well as fundamentally different epidemic dynamics arising in diverse global contexts and in different demographic groups, appear in the press as an indistinguishable part of this general chaos. This leads many people to question whether the field has anything worthwhile to contribute, and muddies the facts about COVID-19 policies for reducing transmission that most experts agree on, like wearing masks and avoiding large indoor gatherings.

So how do we distinguish an expert from a charlatan? I believe a willingness to say "I don't know" and to openly describe uncertainties, nuances, and limitations of science are all good signs. Thoughtful engagement with questions and new ideas is also an indication of expertise, as opposed to arrogant bluster or a bullish insistence on a particular policy strategy regardless of context (which is almost always an attempt to hide a lack of depth of understanding). Trustworthy experts will direct you to others in their field who know more about particular topics, and will tend to be honest about what is and what isn't "in their lane." For example, some expertise is quite specific to a given subfield: epidemiologists who study non-infectious conditions or nutrition, for example, use different methods from those of infectious disease experts, because they generally don't need to account for the exponential growth that is inherent to a contagion process.

Academic scientists have a specific, technical contribution to make in containing the COVID-19 pandemic and in communicating research findings as they emerge. But the liminal space between scientists and the public is subject to the same undercurrents of sexism, racism, and opportunism that society and the academy have always suffered from. Although none of the proxies for expertise described above are fool-proof, they are at least indicative of integrity and humility—two traits the world is in dire need of at this moment in history.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

A COVID-19 moonshot program challenged chemists around the world to submit ideas for how best to design a drug to target the virus.

By mid-March, Alpha Lee was growing restless. A pioneer of AI-driven drug discovery, Lee leads a team of researchers at the University of Cambridge, but his lab had been closed amidst the government-initiated lockdowns spreading inexorably across Europe.

If the Moonshot proves successful, they hope it could serve as a future benchmark for finding new medicines for chronic diseases.

Having spoken to his collaborators across the globe – many of whom were seeing their own experiments and research projects postponed indefinitely due to the pandemic – he noticed a similar sense of frustration and helplessness in the face of COVID-19.

While there was talk of finding a novel treatment for the virus, Lee was well aware the process was likely to be long and laborious. Traditional methods of drug discovery risked suffering the same fate as the efforts to find a cure for SARS in the early 2000, which took years and were ultimately abandoned long before a drug ever reached the market.

To avoid such an outcome, Lee was convinced that global collaboration was required. Together with a collection of scientists in the UK, US and Israel, he launched the 'COVID Moonshot' – a project which encouraged chemists worldwide to share their ideas for potential drug designs. If the Moonshot proves successful, they hope it could serve as a future benchmark for finding new medicines for chronic diseases.

Solving a Complex Jigsaw

In February, ShanghaiTech University published the first detailed snapshots of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus's proteins using a technique called X-ray crystallography. In particular, they revealed a high-resolution profile of the virus's main protease – the part of its structure that enables it to replicate inside a host – and the main drug target. The images were tantalizing.

"We could see all the tiny pieces sitting in the structure like pieces of a jigsaw," said Lee. "All we needed was for someone to come up with the best idea of joining these pieces together with a drug. Then you'd be left with a strong molecule which sits in the protease, and stops it from working, killing the virus in the process."

Normally, ideas for how best to design such a drug would be kept as carefully guarded secrets within individual labs and companies due to their potential value. But as a result, the steady process of trial and error to reach an optimum design can take years to come to fruition.

However, given the scale of the global emergency, Lee felt that the scientific community would be open to collective brainstorming on a mass scale. "Big Pharma usually wouldn't necessarily do this, but time is of the essence here," he said. "It was a case of, 'Let's just rethink every drug discovery stage to see -- ok, how can we go as fast as we can?'"

On March 13, he launched the COVID moonshot, calling for chemists around the globe to come up with the most creative ideas they could think of, on their laptops at home. No design was too weird or wacky to be considered, and crucially nothing would be patented. The entire project would be done on a not-for-profit basis, meaning that any drug that makes it to market will have been created simply for the good of humanity.

It caught fire: Within just two weeks, more than 2,300 potential drug designs had been submitted. By the middle of July, over 10,000 had been received from scientists around the globe.

The Road Toward Clinical Trials

With so many designs to choose from, the team has been attempting to whittle them down to a shortlist of the most promising. Computational drug discovery experts at Diamond and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, have enabled the Moonshot team to develop algorithms for predicting how quick and easy each design would be to make, and to predict how well each proposed drug might bind to the virus in real life.

The latter is an approach known as computational covalent docking and has previously been used in cancer research. "This was becoming more popular even before COVID-19, with several covalent drugs approved by the FDA in recent years," said Nir London, professor of organic chemistry at the Weizmann Institute, and one of the Moonshot team members. "However, all of these were for oncology. A covalent drug against SARS-CoV-2 will certainly highlight covalent drug-discovery as a viable option."

Through this approach, the team have selected 850 compounds to date, which they have manufactured and tested in various preclinical trials already. Fifty of these compounds - which appear to be especially promising when it comes to killing the virus in a test tube – are now being optimized further.

Lee is hoping that at least one of these potential drugs will be shown to be effective in curing animals of COVID-19 within the next six months, a step that would allow the Moonshot team to reach out to potential pharmaceutical partners to test their compounds in humans.

Future Implications

If the project does succeed, some believe it could open the door to scientific crowdsourcing as a future means of generating novel medicine ideas for other diseases. Frank von Delft, professor of protein science and structural biology at the University of Oxford's Nuffield Department of Medicine, described it as a new form of 'citizen science.'

"There's a vast resource of expertise and imagination that is simply dying to be tapped into," he said.

Others are slightly more skeptical, pointing out that the uniqueness of the current crisis has meant that many scientists were willing to contribute ideas without expecting any future compensation in return. This meant that it was easy to circumvent the traditional hurdles that prevent large-scale global collaborations from happening – namely how to decide who will profit from the final product and who will hold the intellectual property (IP) rights.

"I think it is too early to judge if this is a viable model for future drug discovery," says London. "I am not sure that without the existential threat we would have seen so many contributions, and so many people and institutions willing to waive compensation and future royalties. Many scientists found themselves at home, frustrated that they don't have a way to contribute to the fight against COVID-19, and this project gave them an opportunity. Plus many can get behind the fact that this project has no associated IP and no one will get rich off of this effort. This breaks down a lot of the typical barriers and red-tape for wider collaboration."

"If a drug would sprout from one of these crowdsourced ideas, it would serve as a very powerful argument to consider this mode of drug discovery further in the future."

However the Moonshot team believes that if they can succeed, it will at the very least send a strong statement to policy makers and the scientific community that greater efforts should be made to make such large-scale collaborations more feasible.

"All across the scientific world, we've seen unprecedented adoption of open-science, collaboration and collegiality during this crisis, perhaps recognizing that only a coordinated global effort could address this global challenge," says London. "If a drug would sprout from one of these crowdsourced ideas, it would serve as a very powerful argument to consider this mode of drug discovery further in the future."

[An earlier version of this article was published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]

World’s First “Augmented Reality” Contact Lens Aims to Revolutionize Much More Than Medicine

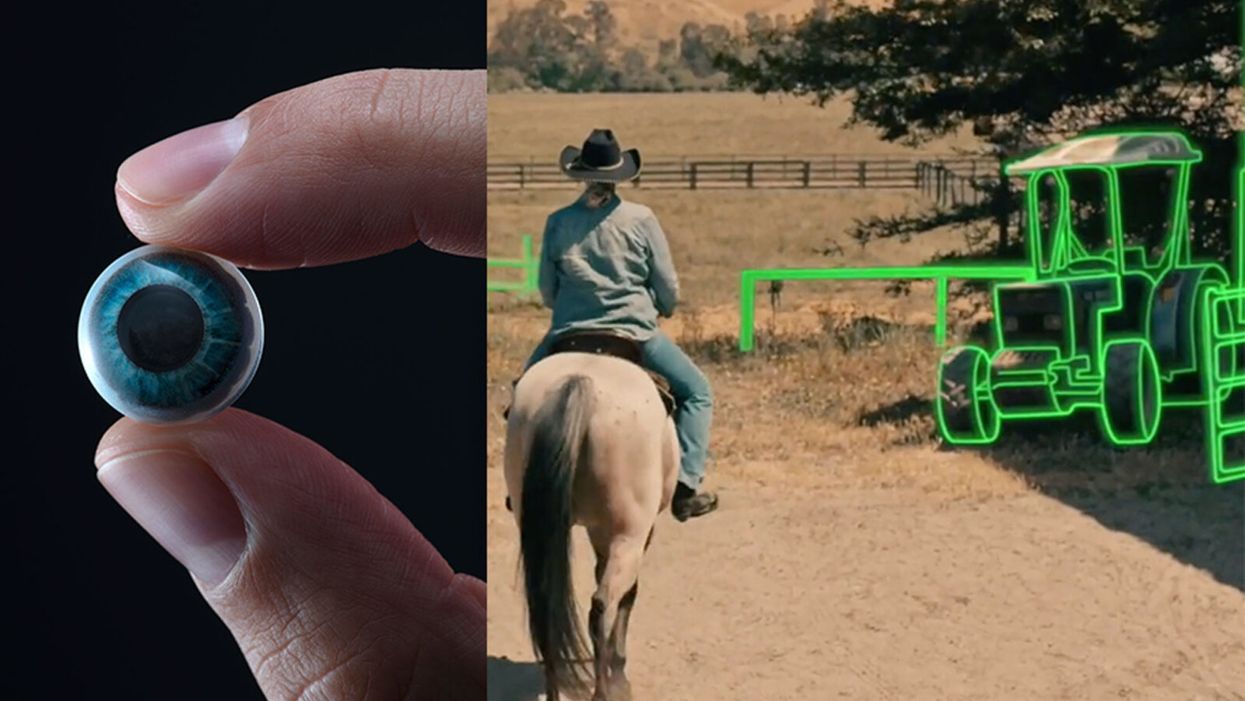

On the left, a picture of the Mojo lens smart contact; and a simulated image of a woman with low vision who is wearing the contact to highlight objects in her field of vision.

Imagine a world without screens. Instead of endlessly staring at your computer or craning your neck down to scroll through social media feeds and emails, information simply appears in front of your eyes when you need it and disappears when you don't.

"The vision is super clear...I was reading the poem with my eyes closed."

No more rude interruptions during dinner, no more bumping into people on the street while trying to follow GPS directions — just the information you want, when you need it, projected directly onto your visual field.

While this screenless future sounds like science fiction, it may soon be a reality thanks to the new Silicon Valley startup Mojo Vision, creator of the world's first smart contact lens. With a 14,000 pixel-per-inch display with eye-tracking, image stabilization, and a custom wireless radio, the Mojo smart lens bills itself the "smallest and densest dynamic display ever made." Unlike current augmented reality wearables such as Google Glass or ThirdEye, which project images onto a glass screen, the Mojo smart lens can project images directly onto the retina.

A current prototype displayed at the Consumer Electronics Show earlier this year in Las Vegas includes a tiny screen positioned right above the most sensitive area of the pupil. "[The Mojo lens] is a contact lens that essentially has wireless power and data transmission for a small micro LED projector that is placed over the center of the eye," explains David Hobbs, Director of Product Management at Mojo Vision. "[It] displays critical heads-up information when you need it and fades into the background when you're ready to continue on with your day."

Eventually, Mojo Visions' technology could replace our beloved smart devices but the first generation of the Mojo smart lens will be used to help the 2.2 billion people globally who suffer from vision impairment.

"If you think of the eye as a camera [for the visually impaired], the sensors are not working properly," explains Dr. Ashley Tuan, Vice President of Medical Devices at Mojo Vision and fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. "For this population, our lens can process the image so the contrast can be enhanced, we can make the image larger, magnify it so that low-vision people can see it or we can make it smaller so they can check their environment." In January of this year, the FDA granted Breakthrough Device Designation to Mojo, allowing them to have early and frequent discussions with the FDA about technical, safety and efficacy topics before clinical trials can be done and certification granted.

For now, Dr. Tuan is one of the few people who has actually worn the Mojo lens. "I put the contact lens on my eye. It was very comfortable like any contact lenses I've worn before," she describes. "The vision is super clear and then when I put on the accessories, suddenly I see Yoda in front of me and I see my vital signs. And then I have my colleague that prepared a beautiful poem that I loved when I was young [and] I was reading the poem with my eyes closed."

At the moment, there are several electronic glasses on the market like Acesight and Nueyes Pro that provide similar solutions for those suffering from visual impairment, but they are large, cumbersome, and highly visible. Mojo lens would be a discreet, more comfortable alternative that offers users more freedom of movement and independence.

"In the case of augmented-reality contact lenses, there could be an opportunity to improve the lives of people with low vision," says Dr. Thomas Steinemann, spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology and professor of ophthalmology at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. "There are existing tools for people currently living with low vision—such as digital apps, magnifiers, etc.— but something wearable could provide more flexibility and significantly more aid in day-to-day tasks."

As one of the first examples of "invisible computing," the potential applications of Mojo lens in the medical field are endless.

According to Dr. Tuan, the visually impaired often suffer from depression due to their lack of mobility and 70 percent of them are underemployed. "We hope that they can use this device to gain their mobility so they can get that social aspect back in their lives and then, eventually, employment," she explains. "That is our first and most important goal."

But helping those with low visual capabilities is only Mojo lens' first possible medical application; augmented reality is already being used in medicine and is poised to revolutionize the field in the coming decades. For example, Accuvein, a device that uses lasers to provide real-time images of veins, is widely used by nurses and doctors to help with the insertion of needles for IVs and blood tests.

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, augmentation of reality has been used in surgery for many years with surgeons using devices such as Google Glass to overlay critical information about their patients into their visual field. Using software like the Holographic Navigation Platform by Scopsis, surgeons can see a mixed-reality overlay that can "show you complicated tumor boundaries, assist with implant placements and guide you along anatomical pathways," its developers say.

However, according to Dr. Tuan, augmented reality headsets have drawbacks in the surgical setting. "The advantage of [Mojo lens] is you don't need to worry about sweating or that the headset or glasses will slide down to your nose," she explains "Also, our lens is designed so that it will understand your intent, so when you don't want the image overlay it will disappear, it will not block your visual field, and when you need it, it will come back at the right time."

As one of the first examples of "invisible computing," the potential applications of Mojo lens in the medical field are endless. Possibilities include live translation of sign language for deaf people; helping those with autism to read emotions; and improving doctors' bedside manner by allowing them to fully engage with patients without relying on a computer.

"[By] monitoring those blood vessels we can [track] chronic disease progression: high blood pressure, diabetes, and Alzheimer's."

Furthermore, the lens could be used to monitor health issues. "We have image sensors in the lens right now that point to the world but we can have a camera pointing inside of your eye to your retina," says Dr. Tuan, "[By] monitoring those blood vessels we can [track] chronic disease progression: high blood pressure, diabetes, and Alzheimer's."

For the moment, the future medical applications of the Mojo lens are still theoretical, but the team is confident they can eventually become a reality after going through the proper regulatory review. The company is still in the process of design, prototype and testing of the lens, so they don't know exactly when it will be available for use, but they anticipate shipping the first available products in the next couple of years. Once it does go to market, it will be available by prescription only for those with visual impairments, but the team's goal is to bring it to broader consumer markets pending regulatory clearance.

"We see that right now there's a unique opportunity here for Mojo lens and invisible computing to help to shape what the next decade of technology development looks like," explains David Hobbs. "We can use [the Mojo lens] to better serve us as opposed to us serving technology better."