Who Qualifies as an “Expert” And How Can We Decide Who Is Trustworthy?

Discerning a real expert from a charlatan is crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

Expertise is a slippery concept. Who has it, who claims it, and who attributes or yields it to whom is a culturally specific, sociological process. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed a remarkable emergence of legitimate and not-so-legitimate scientists publicly claiming or being attributed to have academic expertise in precisely my field: infectious disease epidemiology. From any vantage point, it is clear that charlatans abound out there, garnering TV coverage and hundreds of thousands of Twitter followers based on loud opinions despite flimsy credentials. What is more interesting as an insider is the gradient of expertise beyond these obvious fakers.

A person's expertise is not a fixed attribute; it is a hierarchical trait defined relative to others. Despite my protestations, I am the go-to expert on every aspect of the pandemic to my family. To a reporter, I might do my best to answer a question about the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, noting that I'm not an immunologist. Among other academic scientists, my expertise is more well-defined as a subfield of epidemiology, and within that as a particular area within infectious disease epidemiology. There's a fractal quality to it; as you zoom in on a particular subject, a differentiation of expertise emerges among scientists who, from farther out, appear to be interchangeable.

We all have our scientific domain and are less knowledgeable outside it, of course, and we are often asked to comment on a broad range of topics. But many scientists without a track record in the field have become favorites among university administrators, senior faculty in unrelated fields, policymakers, and science journalists, using institutional prestige or social connections to promote themselves. This phenomenon leads to a distorted representation of science—and of academic scientists—in the public realm.

Trustworthy experts will direct you to others in their field who know more about particular topics, and will tend to be honest about what is and what isn't "in their lane."

Predictably, white male voices have been disproportionately amplified, and men are certainly over-represented in the category of those who use their connections to inappropriately claim expertise. Generally speaking, we are missing women, racial minorities, and global perspectives. This is not only important because it misrepresents who scientists are and reinforces outdated stereotypes that place white men in the Global North at the top of a credibility hierarchy. It also matters because it can promote bad science, and it passes over scientists who can lend nuance to the scientific discourse and give global perspectives on this quintessentially global crisis.

Also at work, in my opinion, are two biases within academia: the conflation of institutional prestige with individual expertise, and the bizarre hierarchy among scientists that attributes greater credibility to those in quantitative fields like physics. Regardless of mathematical expertise or institutional affiliation, lack of experience working with epidemiological data can lead to over-confidence in the deceptively simple mathematical models that we use to understand epidemics, as well as the inappropriate use of uncertain data to inform them. Prominent and vocal scientists from different quantitative fields have misapplied the methods of infectious disease epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic so far, creating enormous confusion among policymakers and the public. Early forecasts that predicted the epidemic would be over by now, for example, led to a sense that epidemiological models were all unreliable.

Meanwhile, legitimate scientific uncertainties and differences of opinion, as well as fundamentally different epidemic dynamics arising in diverse global contexts and in different demographic groups, appear in the press as an indistinguishable part of this general chaos. This leads many people to question whether the field has anything worthwhile to contribute, and muddies the facts about COVID-19 policies for reducing transmission that most experts agree on, like wearing masks and avoiding large indoor gatherings.

So how do we distinguish an expert from a charlatan? I believe a willingness to say "I don't know" and to openly describe uncertainties, nuances, and limitations of science are all good signs. Thoughtful engagement with questions and new ideas is also an indication of expertise, as opposed to arrogant bluster or a bullish insistence on a particular policy strategy regardless of context (which is almost always an attempt to hide a lack of depth of understanding). Trustworthy experts will direct you to others in their field who know more about particular topics, and will tend to be honest about what is and what isn't "in their lane." For example, some expertise is quite specific to a given subfield: epidemiologists who study non-infectious conditions or nutrition, for example, use different methods from those of infectious disease experts, because they generally don't need to account for the exponential growth that is inherent to a contagion process.

Academic scientists have a specific, technical contribution to make in containing the COVID-19 pandemic and in communicating research findings as they emerge. But the liminal space between scientists and the public is subject to the same undercurrents of sexism, racism, and opportunism that society and the academy have always suffered from. Although none of the proxies for expertise described above are fool-proof, they are at least indicative of integrity and humility—two traits the world is in dire need of at this moment in history.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Antibody Testing Alone is Not the Key to Re-Opening Society

Immunity tests have too many unknowns right now to make them very useful in determining protective antibody status.

[Editor's Note: We asked experts from different specialties to weigh in on a timely Big Question: "How should immunity testing play a role in re-opening society?" Below, a virologist offers her perspective.]

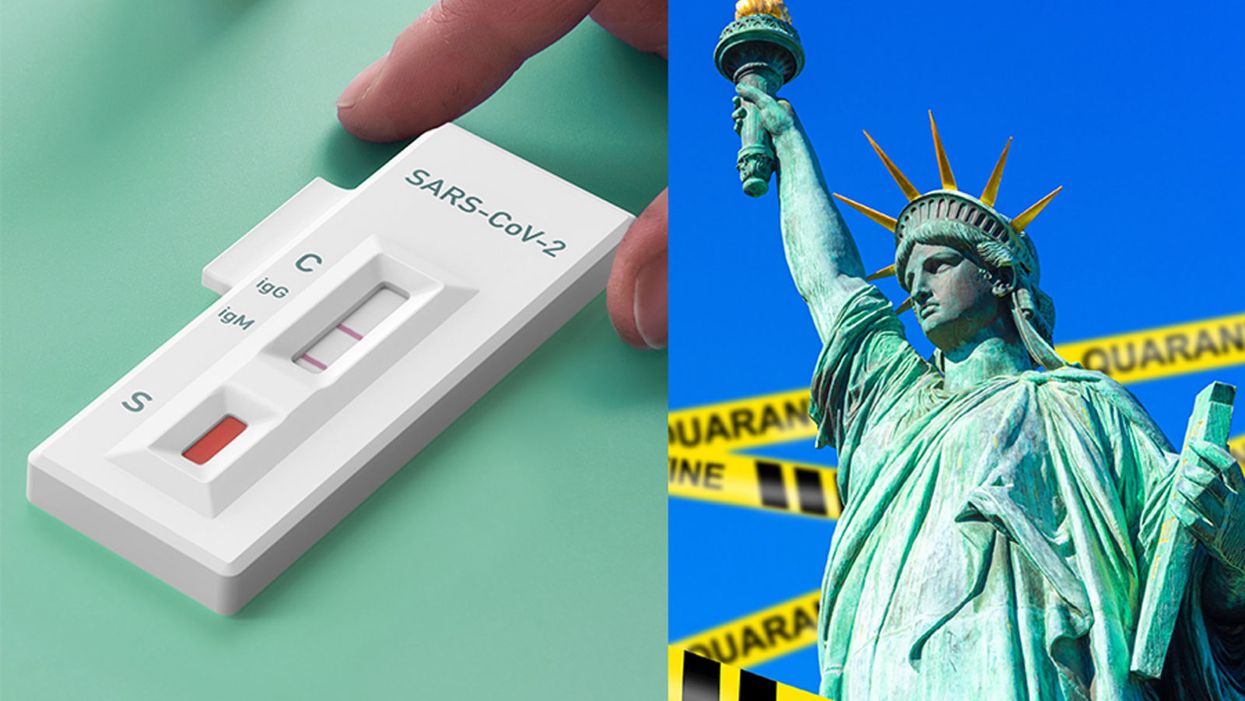

With the advent of serology testing and increased emphasis on "re-opening" America, public health officials have begun considering whether or not people who have recovered from COVID-19 can safely re-enter the workplace.

"Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known."

Conventional wisdom holds that people who have developed antibodies in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, are likely to be immune to reinfection.

For most acute viral infections, this is generally true. However, SARS-CoV-2 is a new pathogen, and there are currently many unanswered questions about immunity. Can recovered patients be reinfected or transmit the virus? Does symptom severity determine how protective responses will be after recovery? How long will protection last? Understanding these basic features is essential to phased re-opening of the government and economy for people who have recovered from COVID-19.

One mechanism that has been considered is issuing "immunity certificates" to individuals with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. These certificates would verify that individuals have already recovered from COVID-19, and thus have antibodies in their blood that will protect them against reinfection, enabling them to safely return to work and participate in society. Although this sounds reasonable in theory, there are many practical reasons why this is not a wise policy decision to ease off restrictive stay-home orders and distancing practices.

Too Many Scientific Unknowns

Serology tests measure antibodies in the serum—the liquid component of blood, which is where the antibodies are located. In this case, serology tests measure antibodies that specifically bind to SARS-CoV-2 virus particles. Usually when a person is infected with a virus, they develop antibodies that can "recognize" that virus, so the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies indicates that a person has been previously exposed to the virus. Broad serology testing is critical to knowing how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, since testing capacity for the virus itself has been so low.

Tests for the virus measure amounts of SARS-CoV-2 RNA—the virus's genetic material—directly, and thus will not detect the virus once a person has recovered. Thus, the majority of people who were not severely ill and did not require hospitalization, or did not have direct contact with a confirmed case, will not test positive for the virus weeks after they have recovered and can only determine if they had COVID-19 by testing for antibodies.

In most cases, for most pathogens, antibodies are also neutralizing, meaning they bind to the virus and render it incapable of infecting cells, and this protects against future infections. Immunity certificates are based on the assumption that people with antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 will be protected against reinfection. The problem is that we've only known that SARS-CoV-2 existed for a little over four months. Although studies so far indicate that most (but not all) patients with confirmed COVID-19 cases develop antibodies, we don't know the extent to which antibodies are protective against reinfection, or how long that protection will last. Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known.

The limited data so far is encouraging with regard to protective immunity. Most of the patient sera tested for antibodies show reasonable titers of IgG, the type of antibodies most likely to be neutralizing. Furthermore, studies have shown that these IgG antibodies are capable of neutralizing surrogate viruses as well as infectious SARS-CoV-2 in laboratory tests. In addition, rhesus monkeys that were experimentally infected with SARS-CoV-2 and allowed to recover were protected from reinfection after a subsequent experimental challenge. These data tentatively suggest that most people are likely to develop neutralizing IgG, and protective immunity, after being infected by SARS-CoV-2.

However, not all COVID-19 patients do produce high levels of antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2. A small number of patients in one study had no detectable neutralizing IgG. There have also been reports of patients in South Korea testing PCR positive after a prior negative test, indicating reinfection or reactivation. These cases may be explained by the sensitivity of the PCR test, and no data have been produced to indicate that these cases are genuine reinfection or recurrence of viral infection.

Complicating matters further, not all serology tests measure antibody titers. Some rapid serology tests are designed to be binary—the test can either detect antibodies or not, but does not give information about the amount of antibodies circulating. Based on our current knowledge, we cannot be certain that merely having any level of detectable antibodies alone guarantees protection from reinfection, or from a subclinical reinfection that might not cause a second case of COVID-19, but could still result in transmission to others. These unknowns remain problematic even with tests that accurately detect the presence of antibodies—which is not a given today, as many of the newly available tests are reportedly unreliable.

A Logistical and Ethical Quagmire

While most people are eager to cast off the isolation of physical distancing and resume their normal lives, mere desire to return to normality is not an indicator of whether those antibodies actually work, and no certificate can confer immune protection. Furthermore, immunity certificates could lead to some complicated logistical and ethical issues. If antibodies do not guarantee protective immunity, certifying that they do could give antibody-positive people a false sense of security, causing them to relax infection control practices such as distancing and hand hygiene.

"We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper."

Certificates could be forged, putting susceptible people at higher exposure risk. It's not clear who would issue them, what they would entitle the bearer to do or not do, or how certification would be verified or enforced. There are many ways in which such certificates could be used as a pretext to discriminate against people based on health status, in addition to disability, race, and socioeconomic status. Tracking people based on immune status raises further concerns about privacy and civil rights.

Rather than issuing documents confirming immune status, we should instead "re-open" society cautiously, with widespread virus and serology testing to accurately identify and isolate infected cases rapidly, with immediate contact tracing to safely quarantine and monitor those at exposure risk. Broad serosurveillance must be coupled with functional assays for neutralization activity to begin assessing how protective antibodies might actually be against SARS-CoV-2 infection. To understand how long immunity lasts, we should study antibodies, as well as the functional capabilities of other components of the larger immune system, such as T cells, in recovered COVID-19 patients over time.

We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper. Re-opening society, the government, and the economy depends not only on accurately determining how many people have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, but on a deeper understanding of how those antibodies work to provide protection.

Harvard Researchers Are Using a Breakthrough Tool to Find the Antibodies That Best Knock Out the Coronavirus

Knowing which antibodies bind best to the coronavirus can help guide new medicines and vaccine development.

To find a cure for a deadly infectious disease in the 1995 medical thriller Outbreak, scientists extract the virus's antibodies from its original host—an African monkey.

"When a person is infected, the immune system makes antibodies kind of blindly."

The antibodies prevent the monkeys from getting sick, so doctors use these antibodies to make the therapeutic serum for humans. With SARS-CoV-2, the original hosts might be bats or pangolins, but scientists don't have access to either, so they are turning to the humans who beat the virus.

Patients who recovered from COVID-19 are valuable reservoirs of viral antibodies and may help scientists develop efficient therapeutics, says Stephen J. Elledge, professor of genetics and medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Studying the structure of the antibodies floating in their blood can help understand what their immune systems did right to kill the pathogen.

When viruses invade the body, the immune system builds antibodies against them. The antibodies work like Velcro strips—they use special spots on their surface called paratopes to cling to the specific spots on the viral shell called epitopes. Once the antibodies circulating in the blood find their "match," they cling on to the virus and deactivate it.

But that process is far from simple. The epitopes and paratopes are built of various peptides that have complex shapes, are folded in specific ways, and may carry an electrical charge that repels certain molecules. Only when all of these parameters match, an antibody can get close enough to a viral particle—and shut it out.

So the immune system forges many different antibodies with varied parameters in hopes that some will work. "When a person is infected, the immune system makes antibodies kind of blindly," Elledge says. "It's doing a shotgun approach. It's not sure which ones will work, but it knows once it's made a good one that works."

Elledge and his team want to take the guessing out of the process. They are using their home-built tool VirScan to comb through the blood samples of the recovered COVID-19 patients to see what parameters the efficient antibodies should have. First developed in 2015, the VirScan has a library of epitopes found on the shells of viruses known to afflict humans, akin to a database of criminals' mug shots maintained by the police.

Originally, VirScan was meant to reveal which pathogens a person overcame throughout a lifetime, and could identify over 1,000 different strains of viruses and bacteria. When the team ran blood samples against the VirScan's library, the tool would pick out all the "usual suspects." And unlike traditional blood tests called ELISA, which can only detect one pathogen at a time, VirScan can detect all of them at once. Now, the team has updated VirScan with the SARS-CoV-2 "mug shot" and is beginning to test which antibodies from the recovered patients' blood will bind to them.

Knowing which antibodies bind best can also help fine-tune vaccines.

Obtaining blood samples was a challenge that caused some delays. "So far most of the recovered patients have been in China and those samples are hard to get," Elledge says. It also takes a person five to 10 days to develop antibodies, so the blood must be drawn at the right time during the illness. If a person is asymptomatic, it's hard to pinpoint the right moment. "We just got a couple of blood samples so we are testing now," he said. The team hopes to get some results very soon.

Elucidating the structure of efficient antibodies can help create therapeutics for COVID-19. "VirScan is a powerful technology to study antibody responses," says Harvard Medical School professor Dan Barouch, who also directs the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research. "A detailed understanding of the antibody responses to COVID-19 will help guide the design of next-generation vaccines and therapeutics."

For example, scientists can synthesize antibodies to specs and give them to patients as medicine. Once vaccines are designed, medics can use VirScan to see if those vaccinated again COVID-19 generate the necessary antibodies.

Knowing which antibodies bind best can also help fine-tune vaccines. Sometimes, viruses cause the immune system to generate antibodies that don't deactivate it. "We think the virus is trying to confuse the immune system; it is its business plan," Elledge says—so those unhelpful antibodies shouldn't be included in vaccines.

More importantly, VirScan can also tell which people have developed immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and can return to their workplaces and businesses, which is crucial to restoring the economy. Knowing one's immunity status is especially important for doctors working on the frontlines, Elledge notes. "The resistant ones can intubate the sick."

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.