Why Are Autism Rates Steadily Rising?

Stefania Sterling with her son Charlie, who was diagnosed at age 3 with autism.

Stefania Sterling was just 21 when she had her son, Charlie. She was young and healthy, with no genetic issues apparent in either her or her husband's family, so she expected Charlie to be typical.

"It is surprising that the prevalence of a significant disorder like autism has risen so consistently over a relatively brief period."

It wasn't until she went to a Mommy and Me music class when he was one, and she saw all the other one-year-olds walking, that she realized how different her son was. He could barely crawl, didn't speak, and made no eye contact. By the time he was three, he was diagnosed as being on the lower functioning end of the autism spectrum.

She isn't sure why it happened – and researchers, too, are still trying to understand the basis of the complex condition. Studies suggest that genes can act together with influences from the environment to affect development in ways that lead to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). But rates of ASD are rising dramatically, making the need to figure out why it's happening all the more urgent.

The Latest News

Indeed, the CDC's latest autism report, released last week, which uses 2016 data, found that the prevalence of ASD in four-year-old children was one in 64 children, or 15.6 affected children per 1,000. That's more than the 14.1 rate they found in 2014, for the 11 states included in the study. New Jersey, as in years past, was the highest, with 25.3 per 1,000, compared to Missouri, which had just 8.8 per 1,000.

The rate for eight-year-olds had risen as well. Researchers found the ASD prevalence nationwide was 18.5 per 1,000, or one in 54, about 10 percent higher than the 16.8 rate found in 2014. New Jersey, again, was the highest, at one in 32 kids, compared to Colorado, which had the lowest rate, at one in 76 kids. For New Jersey, that's a 175 percent rise from the baseline number taken in 2000, when the state had just one in 101 kids.

"It is surprising that the prevalence of a significant disorder like autism has risen so consistently over a relatively brief period," said Walter Zahorodny, an associate professor of pediatrics at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, who was involved in collecting the data.

The study echoed the findings of a surprising 2011 study in South Korea that found 1 in every 38 students had ASD. That was the the first comprehensive study of autism prevalence using a total population sample: A team of investigators from the U.S., South Korea, and Canada looked at 55,000 children ages 7 to 12 living in a community in South Korea and found that 2.64 percent of them had some level of autism.

Searching for Answers

Scientists can't put their finger on why rates are rising. Some say it's better diagnosis. That is, it's not that more people have autism. It's that we're better at detecting it. Others attribute it to changes in the diagnostic criteria. Specifically, the May 2013 update of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 -- the standard classification of mental disorders -- removed the communication deficit from the autism definition, which made more children fall under that category. Cynical observers believe physicians and therapists are handing out the diagnosis more freely to allow access to services available only to children with autism, but that are also effective for other children.

Alycia Halladay, chief science officer for the Autism Science Foundation in New York, said she wishes there were just one answer, but there's not. While she believes the rising ASD numbers are due in part to factors like better diagnosis and a change in the definition, she does not believe that accounts for the entire rise in prevalence. As for the high numbers in New Jersey, she said the state has always had a higher prevalence of autism compared to other states. It is also one of the few states that does a good job at recording cases of autism in its educational records, meaning that children in New Jersey are more likely to be counted compared to kids in other states.

"Not every state is as good as New Jersey," she said. "That accounts for some of the difference compared to elsewhere, but we don't know if it's all of the difference in prevalence, or most of it, or what."

"What we do know is that vaccinations do not cause autism."

There is simply no defined proven reason for these increases, said Scott Badesch, outgoing president and CEO of the Autism Society of America.

"There are suggestions that it is based on better diagnosis, but there are also suggestions that the incidence of autism is in fact increasing due to reasons that have yet been determined," he said, adding, "What we do know is that vaccinations do not cause autism."

Zahorodny, the pediatrics professor, believes something is going on beyond better detection or evolving definitions.

"Changes in awareness and shifts in how children are identified or diagnosed are relevant, but they only take you so far in accounting for an increase of this magnitude," he said. "We don't know what is driving the surge in autism recorded by the ADDM Network and others."

He suggested that the increase in prevalence could be due to non-genetic environmental triggers or risk factors we do not yet know about, citing possibilities including parental age, prematurity, low birth rate, multiplicity, breech presentation, or C-section delivery. It may not be one, but rather several factors combined, he said.

"Increases in ASD prevalence have affected the whole population, so the triggers or risks must be very widely dispersed across all strata," he added.

There are studies that find new risk factors for ASD almost on a daily basis, said Idan Menashe, assistant professor in the Department of Health at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the fastest growing research university in Israel.

"There are plenty of studies that find new genetic variants (and new genes)," he said. In addition, various prenatal and perinatal risk factors are associated with a risk of ASD. He cited a study his university conducted last year on the relationship between C-section births and ASD, which found that exposure to general anesthesia may explain the association.

Whatever the cause, health practitioners are seeing the consequences in real time.

"People say rates are higher because of the changes in the diagnostic criteria," said Dr. Roseann Capanna-Hodge, a psychologist in Ridgefield, CT. "And they say it's easier for children to get identified. I say that's not the truth and that I've been doing this for 30 years, and that even 10 years ago, I did not see the level of autism that I do see today."

Sure, we're better at detecting autism, she added, but the detection improvements have largely occurred at the low- to mid- level part of the spectrum. The higher rates of autism are occurring at the more severe end, in her experience.

A Polarizing Theory

Among the more controversial risk factors scientists are exploring is the role environmental toxins may play in the development of autism. Some scientists, doctors and mental health experts suspect that toxins like heavy metals, pesticides, chemicals, or pollution may interrupt the way genes are expressed or the way endocrine systems function, manifesting in symptoms of autism. But others firmly resist such claims, at least until more evidence comes forth. To date, studies have been mixed and many have been more associative than causative.

"Today, scientists are still trying to figure out whether there are other environmental changes that can explain this rise, but studies of this question didn't provide any conclusive answer," said Menashe, who also serves as the scientific director of the National Autism Research Center at BGU.

"It's not everything that makes Charlie. He's just like any other kid."

That inconclusiveness has not dissuaded some doctors from taking the perspective that toxins do play a role. "Autism rates are rising because there is a mismatch between our genes and our environment," said Julia Getzelman, a pediatrician in San Francisco. "The majority of our evolution didn't include the kinds of toxic hits we are experiencing. The planet has changed drastically in just the last 75 years –- it has become more and more polluted with tens of thousands of unregulated chemicals being used by industry that are having effects on our most vulnerable."

She cites BPA, an industrial chemical that has been used since the 1960s to make certain plastics and resins. A large body of research, she says, has shown its impact on human health and the endocrine system. BPA binds to our own hormone receptors, so it may negatively impact the thyroid and brain. A study in 2015 was the first to identify a link between BPA and some children with autism, but the relationship was associative, not causative. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration maintains that BPA is safe at the current levels occurring in food, based on its ongoing review of the available scientific evidence.

Michael Mooney, President of St. Louis-based Delta Genesis, a non-profit organization that treats children struggling with neurodevelopmental delays like autism, suspects a strong role for epigenetics, which refers to changes in how genes are expressed as a result of environmental influences, lifestyle behaviors, age, or disease states.

He believes some children are genetically predisposed to the disorder, and some unknown influence or combination of influences pushes them over the edge, triggering epigenetic changes that result in symptoms of autism.

For Stefania Sterling, it doesn't really matter how or why she had an autistic child. That's only one part of Charlie.

"It's not everything that makes Charlie," she said. "He's just like any other kid. He comes with happy moments. He comes with sad moments. Just like my other three kids."

Why Don’t We Have Artificial Wombs for Premature Infants?

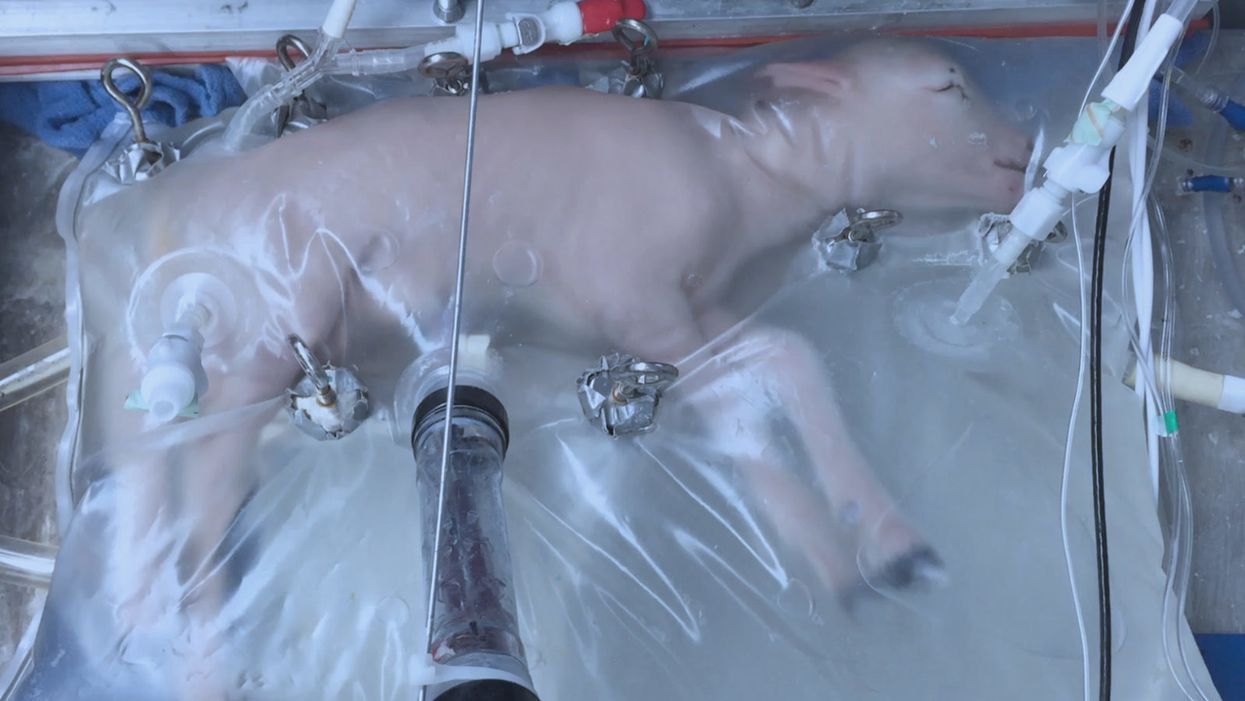

A lamb which was prematurely born at the equivalent of 23 weeks' human gestation, after 28 days of support from an artificial womb.

Ectogenesis, the development of a baby outside of the mother's body, is a concept that dates back to 1923. That year, British biochemist-geneticist J.B.S. Haldane gave a lecture to the "Heretics Society" of the University of Cambridge in which he predicted the invention of an artificial womb by 1960, leading to 70 percent of newborns being born that way by the 2070s. In reality, that's about when an artificial womb could be clinically operational, but trends in science and medicine suggest that such technology would come in increments, each fraught with ethical and social challenges.

An extra-uterine support device could be ready for clinical trials in humans in the next two to four years, with hopes that it could improve survival of very premature infants.

Currently, one major step is in the works, a system called an extra-uterine support device (EUSD) –or sometimes Ex-Vivo uterine Environment (EVE)– which researchers at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia have been using to support fetal lambs outside the mother. It also has been called an artificial placenta, because it supplies nutrient- and oxygen-rich blood to the developing lambs via the umbilical vein and receives blood full of waste products through the umbilical arteries. It does not do everything that a natural placenta does, yet it does do some things that a placenta doesn't do. It breathes for the fetus like the mother's lungs, and encloses the fetus in sterile fluid, just like the amniotic sac. It represents a solution to one set of technical challenges in the path to an artificial womb, namely how to keep oxygen flowing into a fetus and carbon dioxide flowing out when the fetal lungs are not ready to function.

Capable of supporting fetal lambs physiologically equivalent to a human fetus at 23 weeks' gestation or earlier, the EUSD could be ready for clinical trials in humans in the next two to four years, with hopes that it could improve survival of very premature infants. Existing medical technology can keep human infants alive when born in this 23-week range, or even slightly less —the record is just below 22 weeks. But survival is low, because most of the treatment is directed at the lungs, the last major body system to mature to a functional status. This leads to complications not only in babies born before 24 weeks' gestation, but also in a fairly large number of births up to 28 weeks' gestation.

So, the EUSD is basically an advanced neonatal life support machine that beckons to square off the survival curve for infants born up to the 28th week. That is no doubt a good thing, but given the political prominence of reproductive issues, might any societal obstacles be looming?

"While some may argue that the EUSD system will shift the definition of viability to a point prior to the maturation of the fetus' lungs, ethical and legal frameworks must still recognize the mother's privacy rights as paramount."

Health care attorney and clinical ethicist David N. Hoffman points out that even though the EUSD may shift the concept of fetal viability away from the maturity of developing lungs, it would not change the current relationship of the fetus to the mother during pregnancy.

"Our social and legal frameworks, including Roe v. Wade, invite the view of the embryo-fetus as resembling a parasite. Not in a negative sense, but functionally, since it obtains its life support from the mother, while she does not need the fetus for her own physical health," notes Hoffman, who holds faculty appointments at Columbia University, and at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, of Yeshiva University. "In contrast, our ethical conception of the relationship is grounded in the nurturing responsibility of parenthood. We prioritize the welfare of both mother and fetus ethically, but we lean toward the side of the mother's legal rights, regarding her health throughout pregnancy, and her right to control her womb for most of pregnancy. While some may argue that the EUSD system will shift the definition of viability to a point prior to the maturation of the fetus' lungs, ethical and legal frameworks must still recognize the mother's privacy rights as paramount, on the basis of traditional notions of personhood and parenthood."

Outside of legal frameworks, religion, of course, is a major factor in how society reacts to new reproductive technologies, and an artificial womb would trigger a spectrum of responses.

"Significant numbers of conservative Christians may oppose an artificial womb in fear that it might harm the central role of marriage in Christianity."

Speaking from the perspective of Lutheran scholarship, Dr. Daniel Deen, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Concordia University in Irvine, Calif., does not foresee any objections to the EUSD, either theologically, or generally from Lutherans (who tend to be conservative on reproductive issues), since the EUSD is basically an improvement on current management of prematurity. But things would change with the advent of a full-blown artificial womb.

"Significant numbers of conservative Christians may oppose an artificial womb in fear that it might harm the central role of marriage in Christianity," says Deen, who specializes in the philosophy of science. "They may see the artificial womb as a catalyst for strengthening the mechanistic view of reproduction that dominates the thinking of secular society, and of other religious groups, including more liberal Christians."

Judaism, however, appears to be more receptive, even during the research phases.

"Even if researchers strive for a next-generation EUSD aimed at supporting a fetus several weeks earlier than possible with the current system, it still keeps the fetus inside the mother well beyond the 40-day threshold, so there likely are no concerns in terms of Jewish law," says Kalman Laufer, a rabbinical student and executive director of the Medical Ethics Society at Yeshiva University. Referring to a concept from the Babylonian Talmud that an embryo is "like water" until 40 days into pregnancy, at which time it receives a kind of almost-human status warranting protection, Laufer cautions that he's speaking about artificial wombs developed for the sake of rescuing very premature infants. At the same time though, he expects that artificial womb research will eventually trigger a series of complex, legalistic opinions from Jewish scholars, as biotechnology moves further toward supporting fetal growth entirely outside a woman's body.

"Since [the EUSD] gives some justification to end abortion, by transferring fetuses from mother to machine, conservatives will probably rally around it."

While the technology treads into uncomfortable territory for social conservatives at first glance, it's possible that the prospect of taking the abortion debate in a whole new direction could engender support for the artificial womb. "Since [the EUSD] gives some justification to end abortion, by transferring fetuses from mother to machine, conservatives will probably rally around it," says Zoltan Istvan, a transhumanist politician and journalist who ran for U.S. president in 2016. To some extent, Deen agrees with Istvan, provided we get to a point when the artificial womb is already a reality.

"The world has a way of moving forward despite the fear of its inhabitants," Deen notes. "If the technology gets developed, I could not see any Christians, liberal or conservative, arguing that people seeking abortion ought not opt for a 'transfer' versus an abortive procedure."

So then how realistic is a full-blown artificial womb? The researchers at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia have noted various technical difficulties that would come up in any attempt to connect a very young fetus to the EUSD and maintain life. One issue is the small umbilical cord blood vessels that must be connected to the EUSD as fetuses of decreasing gestational age are moved outside the mother. Current procedures might be barely adequate for integrating a human fetus into the device in the 18 -21 week range, but going to lower gestational ages would require new technology and different strategies. It also would require numerous other factors to cover for fetal body systems that mature ahead of the lungs and that the current EUSD system is not designed to replace. However, biotechnology and tissue engineering strategies on the horizon could be added to later EUSDs. To address the blood vessel size issue, artificial womb research could benefit by drawing on experts in microfluidics, the field concerned with manipulation of tiny amounts of fluid through very small spaces, and which is ushering in biotech innovations like the "lab on a chip".

"The artificial womb might put fathers on equal footing with mothers, since any embryo could potentially achieve personhood without ever seeing the inside of a woman's uterus."

If the technical challenges to an artificial womb are indeed overcome, reproductive policy debates could be turned on their side.

"Evolution of the EUSD into a full-blown artificial external uterus has ramifications for any reproductive rights issues where policy currently assumes that a mother is needed for a fertilized egg to become a person," says Hoffman, the ethicist and legal scholar. "If we consider debates over whether to keep cryopreserved human embryos in storage, destroy them, or utilize them for embryonic stem cell research or therapies, the artificial womb might put fathers on equal footing with mothers, since any embryo could potentially achieve personhood without ever seeing the inside of a woman's uterus."

Such a scenario, of course, depends on today's developments not being curtailed or sidetracked by societal objections before full-blown ectogenesis is feasible. But if this does ever become a reality, the history of other biotechnologies suggests that some segment of society will embrace the new innovation and never look back.

Artificial Intelligence Needs Doctors As Much As They Need It

In this futuristic medical concept, a doctor assesses a patient with robust machine assistance.

The media loves to hype concerns about artificial intelligence: What if machines become super-intelligent and self-aware? How will humanity compete and survive? But artificial intelligence today is a far cry from a robot takeover. "AI" is a catch-all term that often refers to machine training or machine learning: There is an abundance of data, vastly more than the human mind can assimilate, being tagged, captured and stored. This systematic data processing requires methodologies that can put it in usable form and formats. While these new developments stoke fear in some corners, the ability to predict outcomes is generally seen as a good thing, as it can mitigate risks and even save lives.

We, collectively, want AI even though it is seldom expressed this way.

The prospects and attempts toward artificial intelligence has been with us for decades. Only recently have the underlying technologies and infrastructure--including computer processing, storage, networking speed and advanced software platforms--become omnipresent. These technological advances enabled the implementation of data mining concepts and the subsequent advantages that were not feasible just a decade ago.

AI is fantastical by vision, evolutionary by experience, and disruptive upon reflection. In the world of health care, AI is already transforming research and clinical practice. We, collectively, want AI even though it is seldom expressed this way. What we, the patient population, patient advocates and caregivers, agree on and want is: (1) timely, precise and inexpensive diagnoses of our ailments, injuries and disorders; (2) timely, personalized, highly effective and efficient courses of therapies; and (3) expedited recovery with minimum deficits, complications and recurrence.

"Artificial intelligence and machine learning will impact healthcare as profoundly as the discovery of the microscope."

Implicitly, we all are saying that we want our healthcare systems and clinicians to accomplish truly inhuman feats: to incorporate all sources of structured data (such as published statistics and reports) and unstructured data (including news articles, conversational analysis by care givers, nuances of similar cases, talks at professional societies); to analyze the data sourced and uncover patterns, reveal side effects, define probable success and outcomes; and to present the best personalized course of treatment for the patient that addresses the ailment and mitigates associated risks. It is hard to argue against any of this.

In a recent published interview, Keith J. Dreyer, executive director of the Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital Center for Clinical Data Science, says that "artificial intelligence and machine learning will impact healthcare as profoundly as the discovery of the microscope."

But as AI helps physicians in profound ways, like detecting subtle lesions on scans or distinguishing the symptoms of a stroke from a brain tumor, we humans can't get too complacent. Evolving AI platforms will provide more sophisticated sets of "tools" to address both mundane and complex medical challenges, albeit with humans very much in the mix and routinely at the helm.

Humans do not appear endangered to be replaced anytime soon.

Human beings are capable of a level of nuance and contextual understanding of complex medical scenarios and, consequently, do not appear endangered to be replaced anytime soon. These platforms will do some heavy lifting for sure and provide considerable assistance across the healthcare industry. But human involvement is crucial, as we are best at adaptive learning, cognition, ensuring accuracy of the data, and continually providing feedback to improve the machine learning components of the AI platforms that the health industry will increasingly rely upon.

The human/machine interface is not binary; there is no line in the sand. It is fuzzy and evolutionary, a synchronicity that we all will surely witness and experience. In the future, it may be possible that all recorded knowledge, including genetic, genomic and laboratory data, from structured and unstructured sources, can be at the fingertips of your clinician, and then factored into diagnosing your condition and prescribing your course of treatment. This is precision and personalized medicine on a grand scale applied at the micro level--you!

But none of this will diminish the importance of doctors, nurses and all assortment of care providers. Though they all will undoubtedly become more effective with such awesome AI assistance, their job will always be to heal you with compassion, wisdom, and kindness, for the essence of humanity cannot be automated.