Why Your Brain Falls for Misinformation – And How to Avoid It

Understanding the vulnerabilities of our own brains can help us guard against fake news.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

Whenever you hear something repeated, it feels more true. In other words, repetition makes any statement seem more accurate. So anything you hear again will resonate more each time it's said.

Do you see what I did there? Each of the three sentences above conveyed the same message. Yet each time you read the next sentence, it felt more and more true. Cognitive neuroscientists and behavioral economists like myself call this the "illusory truth effect."

Go back and recall your experience reading the first sentence. It probably felt strange and disconcerting, perhaps with a note of resistance, as in "I don't believe things more if they're repeated!"

Reading the second sentence did not inspire such a strong reaction. Your reaction to the third sentence was tame by comparison.

Why? Because of a phenomenon called "cognitive fluency," meaning how easily we process information. Much of our vulnerability to deception in all areas of life—including to fake news and misinformation—revolves around cognitive fluency in one way or another. And unfortunately, such misinformation can swing major elections.

The Lazy Brain

Our brains are lazy. The more effort it takes to process information, the more uncomfortable we feel about it and the more we dislike and distrust it.

By contrast, the more we like certain data and are comfortable with it, the more we feel that it's accurate. This intuitive feeling in our gut is what we use to judge what's true and false.

Yet no matter how often you heard that you should trust your gut and follow your intuition, that advice is wrong. You should not trust your gut when evaluating information where you don't have expert-level knowledge, at least when you don't want to screw up. Structured information gathering and decision-making processes help us avoid the numerous errors we make when we follow our intuition. And even experts can make serious errors when they don't rely on such decision aids.

These mistakes happen due to mental errors that scholars call "cognitive biases." The illusory truth effect is one of these mental blindspots; there are over 100 altogether. These mental blindspots impact all areas of our life, from health and politics to relationships and even shopping.

We pay the most attention to whatever we find most emotionally salient in our environment, as that's the information easiest for us to process.

The Maladapted Brain

Why do we have so many cognitive biases? It turns out that our intuitive judgments—our gut reactions, our instincts, whatever you call them—aren't adapted for the modern environment. They evolved from the ancestral savanna environment, when we lived in small tribes of 15–150 people and spent our time hunting and foraging.

It's not a surprise, when you think about it. Evolution works on time scales of many thousands of years; our modern informational environment has been around for only a couple of decades, with the rise of the internet and social media.

Unfortunately, that means we're using brains adapted for the primitive conditions of hunting and foraging to judge information and make decisions in a very different world. In the ancestral environment, we had to make quick snap judgments in order to survive, thrive, and reproduce; we're the descendants of those who did so most effectively.

In the modern environment, we can take our time to make much better judgments by using structured evaluation processes to protect yourself from cognitive biases. We have to train our minds to go against our intuitions if we want to figure out the truth and avoid falling for misinformation.

Yet it feels very counterintuitive to do so. Again, not a surprise: by definition, you have to go against your intuitions. It's not easy, but it's truly the only path if you don't want to be vulnerable to fake news.

The Danger of Cognitive Fluency and Illusory Truth

We already make plenty of mistakes by ourselves, without outside intervention. It's especially difficult to protect ourselves against those who know how to manipulate us. Unfortunately, the purveyors of misinformation excel at exploiting our cognitive biases to get us to buy into fake news.

Consider the illusory truth effect. Our vulnerability to it stems from how our brain processes novel stimuli. The first time we hear something new to us, it's difficult to process mentally. It has to integrate with our existing knowledge framework, and we have to build new neural pathways to make that happen. Doing so feels uncomfortable for our lazy brain, so the statement that we heard seems difficult to swallow to us.

The next time we hear that same thing, our mind doesn't have to build new pathways. It just has to go down the same ones it built earlier. Granted, those pathways are little more than trails, newly laid down and barely used. It's hard to travel down that newly established neural path, but much easier than when your brain had to lay down that trail. As a result, the statement is somewhat easier to swallow.

Each repetition widens and deepens the trail. Each time you hear the same thing, it feels more true, comfortable, and intuitive.

Does it work for information that seems very unlikely? Science says yes! Researchers found that the illusory truth effect applies strongly to implausible as well as plausible statements.

What about if you know better? Surely prior knowledge prevents this illusory truth! Unfortunately not: even if you know better, research shows you're still vulnerable to this cognitive bias, though less than those who don't have prior knowledge.

Sadly, people who are predisposed to more elaborate and sophisticated thinking—likely you, if you're reading the article—are more likely to fall for the illusory truth effect. And guess what: more sophisticated thinkers are also likelier than less sophisticated ones to fall for the cognitive bias known as the bias blind spot, where you ignore your own cognitive biases. So if you think that cognitive biases such as the illusory truth effect don't apply to you, you're likely deluding yourself.

That's why the purveyors of misinformation rely on repeating the same thing over and over and over and over again. They know that despite fact-checking, their repetition will sway people, even some of those who think they're invulnerable. In fact, believing that you're invulnerable will make you more likely to fall for this and other cognitive biases, since you won't be taking the steps necessary to address them.

Other Important Cognitive Biases

What are some other cognitive biases you need to beware? If you've heard of any cognitive biases, you've likely heard of the "confirmation bias." That refers to our tendency to look for and interpret information in ways that conform to our prior beliefs, intuitions, feelings, desires, and preferences, as opposed to the facts.

Again, cognitive fluency deserves blame. It's much easier to build neural pathways to information that we already possess, especially that around which we have strong emotions; it's much more difficult to break well-established neural pathways if we need to change our mind based on new information. Consequently, we instead look for information that's easy to accept, that which fits our prior beliefs. In turn, we ignore and even actively reject information that doesn't fit our beliefs.

Moreover, the more educated we are, the more likely we are to engage in such active rejection. After all, our smarts give us more ways of arguing against new information that counters our beliefs. That's why research demonstrates that the more educated you are, the more polarized your beliefs will be around scientific issues that have religious or political value overtones, such as stem cell research, human evolution, and climate change. Where might you be letting your smarts get in the way of the facts?

Our minds like to interpret the world through stories, meaning explanatory narratives that link cause and effect in a clear and simple manner. Such stories are a balm to our cognitive fluency, as our mind constantly looks for patterns that explain the world around us in an easy-to-process manner. That leads to the "narrative fallacy," where we fall for convincing-sounding narratives regardless of the facts, especially if the story fits our predispositions and our emotions.

You ever wonder why politicians tell so many stories? What about the advertisements you see on TV or video advertisements on websites, which tell very quick visual stories? How about salespeople or fundraisers? Sure, sometimes they cite statistics and scientific reports, but they spend much, much more time telling stories: simple, clear, compelling narratives that seem to make sense and tug at our heartstrings.

Now, here's something that's actually true: the world doesn't make sense. The world is not simple, clear, and compelling. The world is complex, confusing, and contradictory. Beware of simple stories! Look for complex, confusing, and contradictory scientific reports and high-quality statistics: they're much more likely to contain the truth than the easy-to-process stories.

Another big problem that comes from cognitive fluency: the "attentional bias." We pay the most attention to whatever we find most emotionally salient in our environment, as that's the information easiest for us to process. Most often, such stimuli are negative; we feel a lesser but real attentional bias to positive information.

That's why fear, anger, and resentment represent such powerful tools of misinformers. They know that people will focus on and feel more swayed by emotionally salient negative stimuli, so be suspicious of negative, emotionally laden data.

You should be especially wary of such information in the form of stories framed to fit your preconceptions and repeated. That's because cognitive biases build on top of each other. You need to learn about the most dangerous ones for evaluating reality clearly and making wise decisions, and watch out for them when you consume news, and in other life areas where you don't want to make poor choices.

Fixing Our Brains

Unfortunately, knowledge only weakly protects us from cognitive biases; it's important, but far from sufficient, as the study I cited earlier on the illusory truth effect reveals.

What can we do?

The easiest decision aid is a personal commitment to twelve truth-oriented behaviors called the Pro-Truth Pledge, which you can make by signing the pledge at ProTruthPledge.org. All of these behaviors stem from cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics research in the field called debiasing, which refers to counterintuitive, uncomfortable, but effective strategies to protect yourself from cognitive biases.

What are these behaviors? The first four relate to you being truthful yourself, under the category "share truth." They're the most important for avoiding falling for cognitive biases when you share information:

Share truth

- Verify: fact-check information to confirm it is true before accepting and sharing it

- Balance: share the whole truth, even if some aspects do not support my opinion

- Cite: share my sources so that others can verify my information

- Clarify: distinguish between my opinion and the facts

The second set of four are about how you can best "honor truth" to protect yourself from cognitive biases in discussions with others:

Honor truth

- Acknowledge: when others share true information, even when we disagree otherwise

- Reevaluate: if my information is challenged, retract it if I cannot verify it

- Defend: defend others when they come under attack for sharing true information, even when we disagree otherwise

- Align: align my opinions and my actions with true information

The last four, under the category "encourage truth," promote broader patterns of truth-telling in our society by providing incentives for truth-telling and disincentives for deception:

Encourage truth

- Fix: ask people to retract information that reliable sources have disproved even if they are my allies

- Educate: compassionately inform those around me to stop using unreliable sources even if these sources support my opinion

- Defer: recognize the opinions of experts as more likely to be accurate when the facts are disputed

- Celebrate: those who retract incorrect statements and update their beliefs toward the truth

Peer-reviewed research has shown that taking the Pro-Truth Pledge is effective for changing people's behavior to be more truthful, both in their own statements and in interactions with others. I hope you choose to join the many thousands of ordinary citizens—and over 1,000 politicians and officials—who committed to this decision aid, as opposed to going with their gut.

[Adapted from: Dr. Gleb Tsipursky and Tim Ward, Pro Truth: A Practical Plan for Putting Truth Back Into Politics (Changemakers Books, 2020).]

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Thanks to safety cautions from the COVID-19 pandemic, a strain of influenza has been completely eliminated.

If you were one of the millions who masked up, washed your hands thoroughly and socially distanced, pat yourself on the back—you may have helped change the course of human history.

Scientists say that thanks to these safety precautions, which were introduced in early 2020 as a way to stop transmission of the novel COVID-19 virus, a strain of influenza has been completely eliminated. This marks the first time in human history that a virus has been wiped out through non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as vaccines.

The flu shot, explained

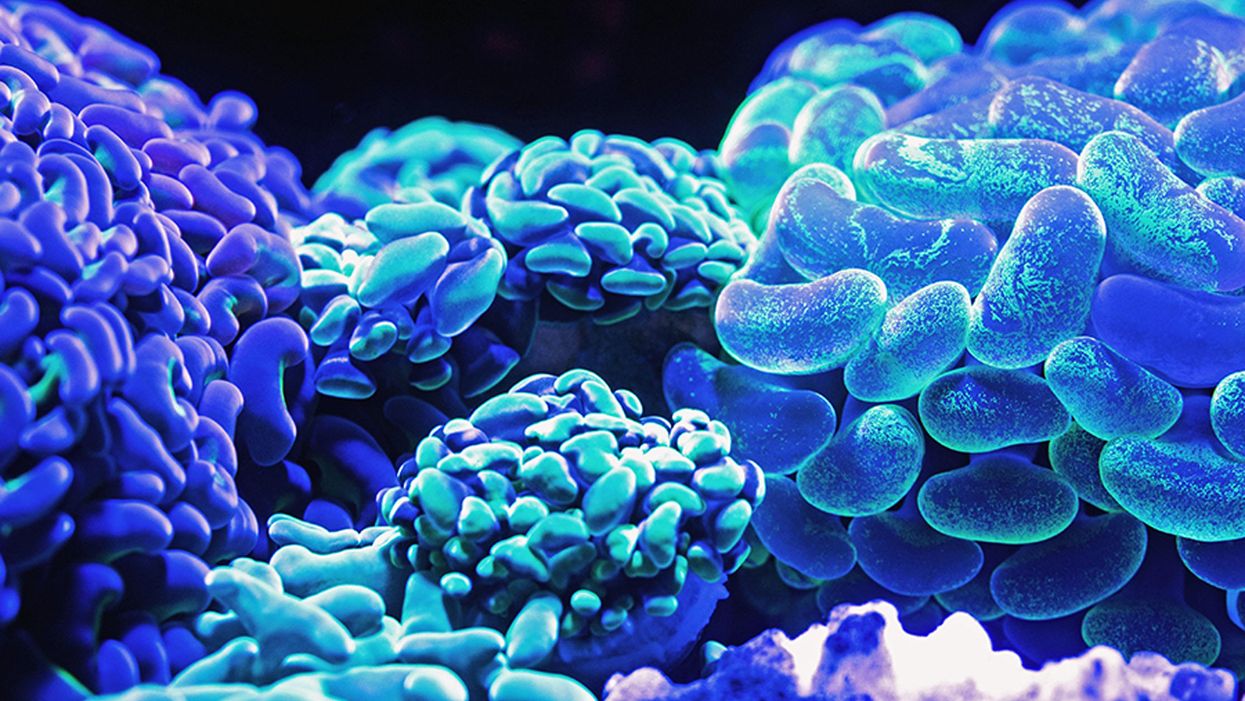

Influenza viruses type A and B are responsible for the majority of human illnesses and the flu season.

Centers for Disease Control

For more than a decade, flu shots have protected against two types of the influenza virus–type A and type B. While there are four different strains of influenza in existence (A, B, C, and D), only strains A, B, and C are capable of infecting humans, and only A and B cause pandemics. In other words, if you catch the flu during flu season, you’re most likely sick with flu type A or B.

Flu vaccines contain inactivated—or dead—influenza virus. These inactivated viruses can’t cause sickness in humans, but when administered as part of a vaccine, they teach a person’s immune system to recognize and kill those viruses when they’re encountered in the wild.

Each spring, a panel of experts gives a recommendation to the US Food and Drug Administration on which strains of each flu type to include in that year’s flu vaccine, depending on what surveillance data says is circulating and what they believe is likely to cause the most illness during the upcoming flu season. For the past decade, Americans have had access to vaccines that provide protection against two strains of influenza A and two lineages of influenza B, known as the Victoria lineage and the Yamagata lineage. But this year, the seasonal flu shot won’t include the Yamagata strain, because the Yamagata strain is no longer circulating among humans.

How Yamagata Disappeared

Flu surveillance data from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) shows that the Yamagata lineage of flu type B has not been sequenced since April 2020.

Nature

Experts believe that the Yamagata lineage had already been in decline before the pandemic hit, likely because the strain was naturally less capable of infecting large numbers of people compared to the other strains. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the resulting safety precautions such as social distancing, isolating, hand-washing, and masking were enough to drive the virus into extinction completely.

Because the strain hasn’t been circulating since 2020, the FDA elected to remove the Yamagata strain from the seasonal flu vaccine. This will mark the first time since 2012 that the annual flu shot will be trivalent (three-component) rather than quadrivalent (four-component).

Should I still get the flu shot?

The flu shot will protect against fewer strains this year—but that doesn’t mean we should skip it. Influenza places a substantial health burden on the United States every year, responsible for hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations and tens of thousands of deaths. The flu shot has been shown to prevent millions of illnesses each year (more than six million during the 2022-2023 season). And while it’s still possible to catch the flu after getting the flu shot, studies show that people are far less likely to be hospitalized or die when they’re vaccinated.

Another unexpected benefit of dropping the Yamagata strain from the seasonal vaccine? This will possibly make production of the flu vaccine faster, and enable manufacturers to make more vaccines, helping countries who have a flu vaccine shortage and potentially saving millions more lives.

After his grandmother’s dementia diagnosis, one man invented a snack to keep her healthy and hydrated.

Founder Lewis Hornby and his grandmother Pat, sampling Jelly Drops—an edible gummy containing water and life-saving electrolytes.

On a visit to his grandmother’s nursing home in 2016, college student Lewis Hornby made a shocking discovery: Dehydration is a common (and dangerous) problem among seniors—especially those that are diagnosed with dementia.

Hornby’s grandmother, Pat, had always had difficulty keeping up her water intake as she got older, a common issue with seniors. As we age, our body composition changes, and we naturally hold less water than younger adults or children, so it’s easier to become dehydrated quickly if those fluids aren’t replenished. What’s more, our thirst signals diminish naturally as we age as well—meaning our body is not as good as it once was in letting us know that we need to rehydrate. This often creates a perfect storm that commonly leads to dehydration. In Pat’s case, her dehydration was so severe she nearly died.

When Lewis Hornby visited his grandmother at her nursing home afterward, he learned that dehydration especially affects people with dementia, as they often don’t feel thirst cues at all, or may not recognize how to use cups correctly. But while dementia patients often don’t remember to drink water, it seemed to Hornby that they had less problem remembering to eat, particularly candy.

Hornby wanted to create a solution for elderly people who struggled keeping their fluid intake up. He spent the next eighteen months researching and designing a solution and securing funding for his project. In 2019, Hornby won a sizable grant from the Alzheimer’s Society, a UK-based care and research charity for people with dementia and their caregivers. Together, through the charity’s Accelerator Program, they created a bite-sized, sugar-free, edible jelly drop that looked and tasted like candy. The candy, called Jelly Drops, contained 95% water and electrolytes—important minerals that are often lost during dehydration. The final product launched in 2020—and was an immediate success. The drops were able to provide extra hydration to the elderly, as well as help keep dementia patients safe, since dehydration commonly leads to confusion, hospitalization, and sometimes even death.

Not only did Jelly Drops quickly become a favorite snack among dementia patients in the UK, but they were able to provide an additional boost of hydration to hospital workers during the pandemic. In NHS coronavirus hospital wards, patients infected with the virus were regularly given Jelly Drops to keep their fluid levels normal—and staff members snacked on them as well, since long shifts and personal protective equipment (PPE) they were required to wear often left them feeling parched.

In April 2022, Jelly Drops launched in the United States. The company continues to donate 1% of its profits to help fund Alzheimer’s research.