With Lab-Grown Chicken Nuggets, Dumplings, and Burgers, Futuristic Foods Aim to Seem Familiar

Shiok Meat's lab-grown "shrimp" dumplings, alongside a photo of the company's CTO, Ka Yi Ling, in a lab.

Sandhya Sriram is at the forefront of the expanding lab-grown meat industry in more ways than one.

"[Lab-grown meat] is kind of a brave new world for a lot of people, and food isn't something people like being brave about."

She's the CEO and co-founder of one of fewer than 30 companies that is even in this game in the first place. Her Singapore-based company, Shiok Meats, is the only one to pop up in Southeast Asia. And it's the only company in the world that's attempting to grow crustaceans in a lab, starting with shrimp. This spring, the company debuted a prototype of its shrimp, and completed a seed funding round of $4.6 million.

Yet despite all of these wins, Sriram's own mother won't try the company's shrimp. She's a staunch, lifelong vegetarian, adhering to a strict definition of what that means.

"[Lab-grown meat] is kind of a brave new world for a lot of people, and food isn't something people like being brave about. It's really a rather hard-wired thing," says Kate Krueger, the research director at New Harvest, a non-profit accelerator for cellular agriculture (the umbrella field that studies how to grow animal products in the lab, including meat, dairy, and eggs).

It's so hard-wired, in fact, that trends in food inform our species' origin story. In 2017, a group of paleoanthropologists caused an upset when they unearthed fossils in present day Morocco showing that our earliest human ancestors lived much further north and 100,000 years earlier than expected -- the remains date back 300,000 years. But the excavation not only included bones and tools, it also painted a clear picture of the prevailing menu at the time: The oldest humans were apparently chomping on tons of gazelle, as well as wildebeest and zebra when they could find them, plus the occasional seasonal ostrich egg.

These were people with a diet shaped by available resources, but also by the ability to cook in the first place. In his book Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, Harvard primatologist Richard Wrangam writes that the very thing that allowed for the evolution of Homo sapiens was the ability to transform raw ingredients into edible nutrients through cooking.

Today, our behavior and feelings around food are the product of local climate, crops, animal populations, and tools, but also religion, tradition, and superstition. So what happens when you add science to the mix? Turns out, we still trend toward the familiar. The innovations in lab-grown meat that are picking up the most steam are foods like burgers, not meat chips, and salmon, not salmon-cod-tilapia hybrids. It's not for lack of imagination, it's because the industry's practitioners know that a lifetime of food memories is a hard thing to contend with. So far, the nascent lab-grown meat industry is not so much disrupting as being shaped by the oldest culture we have.

Not a single piece of lab-grown meat is commercially available to consumers yet, and already so much ink has been spilled debating if it's really meat, if it's kosher, if it's vegetarian, if it's ethical, if it's sustainable. But whether or not the industry succeeds and sticks around is almost moot -- watching these conversations and innovations unfold serves as a mirror reflecting back who we are, what concerns us, and what we aspire to.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

The building blocks for making lab-grown meat right now are remarkably similar, no matter what type of animal protein a company is aiming to produce.

First, a small biopsy, about the size of a sesame seed, is taken from a single animal. Then, the muscle cells are isolated and added to a nutrient-dense culture in a bioreactor -- the same tool used to make beer -- where the cells can multiply, grow, and form muscle tissue. This tissue can then be mixed with additives like nutrients, seasonings, binders, and sometimes colors to form a food product. Whether a company is attempting to make chicken, fish, beef, shrimp, or any other animal protein in a lab, the basic steps remain similar. Cells from various animals do behave differently, though, and each company has its own proprietary techniques and tools. Some, for example, use fetal calf serum as their cell culture, while others, aiming for a more vegan approach, eschew it.

"New gadgets feel safest when they remind us of other objects that we already know."

According to Mark Post, who made the first lab-grown hamburger at Maastricht University in the Netherlands in 2013, the cells of just one cow can give way to 175 million four-ounce burgers. By today's available burger-making methods, you'd need to slaughter 440,000 cows for the same result. The projected difference in the purely material efficiency between the two systems is staggering. The environmental impact is hard to predict, though. Some companies claim that their lab-grown meat requires 99 percent less land and 96 percent less water than traditional farming methods -- and that rearing fewer cows, specifically, would reduce methane emissions -- but the energy cost of running a lab-grown-meat production facility at an industrial scale, especially as compared to small-scale, pasture-raised farming, could be problematic. It's difficult to truly measure any of this in a burgeoning industry.

At this point, growing something like an intact shrimp tail or a marbled steak in a lab is still a Holy Grail. It would require reproducing the complex musculo-skeletal and vascular structure of meat, not just the cellular basis, and no one's successfully done it yet. Until then, many companies working on lab-grown meat are perfecting mince. Each new company's demo of a prototype food feels distinctly regional, though: At the Disruption in Food and Sustainability Summit in March, Shiok (which is pronounced "shook," and is Singaporean slang for "very tasty and delicious") first shared a prototype of its shrimp as an ingredient in siu-mai, a dumpling of Chinese origin and a fixture at dim sum. JUST, a company based in the U.S., produced a demo chicken nugget.

As Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the 17th century founder of the gastronomic essay, famously said, "Show me what you eat, and I'll tell you who you are."

For many of these companies, the baseline animal protein they are trying to innovate also feels tied to place and culture: When meat comes from a bioreactor, not a farm, the world's largest exporter of seafood could be a landlocked region, and beef could be "reared" in a bayou, yet the handful of lab-grown fish companies, like Finless Foods and BlueNalu, hug the American coasts; VOW, based in Australia, started making lab-grown kangaroo meat in August; and of course the world's first lab-grown shrimp is in Singapore.

"In the U.S., shrimps are either seen in shrimp cocktail, shrimp sushi, and so on, but [in Singapore] we have everything from shrimp paste to shrimp oil," Sriram says. "It's used in noodles and rice, as flavoring in cup noodles, and in biscuits and crackers as well. It's seen in every form, shape, and size. It just made sense for us to go after a protein that was widely used."

It's tempting to assume that innovating on pillars of cultural significance might be easier if the focus were on a whole new kind of food to begin with, not your popular dim sum items or fast food offerings. But it's proving to be quite the opposite.

"That could have been one direction where [researchers] just said, 'Look, it's really hard to reproduce raw ground beef. Why don't we just make something completely new, like meat chips?'" says Mike Lee, co-founder and co-CEO of Alpha Food Labs, which works on food innovation more broadly. "While that strategy's interesting, I think we've got so many new things to explain to people that I don't know if you want to also explain this new format of food that you've never, ever seen before."

We've seen this same cautious approach to change before in other ways that relate to cooking. Perhaps the most obvious example is the kitchen range. As Bee Wilson writes in her book Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat, in the 1880s, convincing ardent coal-range users to switch to newfangled gas was a hard sell. To win them over, inventor William Sugg designed a range that used gas, but aesthetically looked like the coal ones already in fashion at the time -- and which in some visual ways harkened even further back to the days of open-hearth cooking. Over time, gas range designs moved further away from those of the past, but the initial jump was only made possible through familiarity. There's a cleverness to meeting people where they are.

"New gadgets feel safest when they remind us of other objects that we already know," writes Wilson. "It is far harder to accept a technology that is entirely new."

Maybe someday we won't want anything other than meat chips, but not today.

Measuring Success

A 2018 Gallup poll shows that in the U.S., rates of true vegetarianism and veganism have been stagnant for as long as they've been measured. When the poll began in 1999, six percent of Americans were vegetarian, a number that remained steady until 2012, when the number dropped one point. As of 2018, it remained at five percent.

In 2012, when Gallup first measured the percentage of vegans, the rate was two percent. By 2018 it had gone up just one point, to three percent. Increasing awareness of animal welfare, health, and environmental concerns don't seem to be incentive enough to convince Americans, en masse, to completely slam the door on a food culture characterized in many ways by its emphasis on traditional meat consumption.

"A lot of consumers get over the ick factor when you tell them that most of the food that you're eating right now has entered the lab at some point."

Wilson writes that "experimenting with new foods has always been a dangerous business. In the wild, trying out some tempting new berries might lead to death. A lingering sense of this danger may make us risk-averse in the kitchen."

That might be one psychologically deep-seated reason that Americans are so resistant to ditch meat altogether. But a middle ground is emerging with a rise in flexitarianism, which aims to reduce reliance on traditional animal products. "Americans are eager to include alternatives to animal products in their diets, but are not willing to give up animal products completely," the same 2018 Gallup poll reported. This may represent the best opportunity for lab-grown meat to wedge itself into the culture.

Quantitatively predicting a population's willingness to try a lab-grown version of its favorite protein is proving a hard thing to measure, however, because it's still science fiction to a regular consumer. Measuring popular opinion of something that doesn't really exist yet is a dubious pastime.

In 2015, University of Wisconsin School of Public Health researchers Linnea Laestadius and Mark Caldwell conducted a study using online comments on articles about lab-grown meat to suss out public response to the food. The results showed a mostly negative attitude, but that was only two years into a field that is six years old today. Already public opinion may have shifted.

Shiok Meat's Sriram and her co-founder Ka Yi Ling have used online surveys to get a sense of the landscape, but they also take a more direct approach sometimes. Every time they give a public talk about their company and their shrimp, they poll their audience before and after the talk, using the question, "How many of you are willing to try, and pay, to eat lab-grown meat?"

They consistently find that the percentage of people willing to try goes up from 50 to 90 percent after hearing their talk, which includes information about the downsides of traditional shrimp farming (for one thing, many shrimp are raised in sewage, and peeled and deveined by slaves) and a bit of information about how lab-grown animal protein is being made now. I saw this pan out myself when Ling spoke at a New Harvest conference in Cambridge, Massachusetts in July.

"A lot of consumers get over the ick factor when you tell them that most of the food that you're eating right now has entered the lab at some point," Sriram says. "We're not going to grow our meat in the lab always. It's in the lab right now, because we're in R&D. Once we go into manufacturing ... it's going to be a food manufacturing facility, where a lot of food comes from."

The downside of the University of Wisconsin's and Shiok Meat's approach to capturing public opinion is that they each look at self-selecting groups: Online commenters are often fueled by a need to complain, and it's likely that anyone attending a talk by the co-founders of a lab-grown meat company already has some level of open-mindedness.

So Sriram says that she and Ling are also using another method to assess the landscape, and it's somewhere in the middle. They've been watching public responses to the closest available product to lab-grown meat that's on the market: Impossible Burger. As a 100 percent plant-based burger, it's not quite the same, but this bleedable, searable patty is still very much the product of science and laboratory work. Its remarkable similarity to beef is courtesy of yeast that have been genetically engineered to contain DNA from soy plant roots, which produce a protein called heme as they multiply. This heme is a plant-derived protein that can look and act like the heme found in animal muscle.

So far, the sciencey underpinnings of the burger don't seem to be turning people off. In just four years, it's already found its place within other American food icons. It's readily available everywhere from nationwide Burger Kings to Boston's Warren Tavern, which has been in operation since 1780, is one of the oldest pubs in America, and is even named after the man who sent Paul Revere on his midnight ride. Some people have already grown so attached to the Impossible Burger that they will actually walk out of a restaurant that's out of stock. Demand for the burger is outpacing production.

"Even though [Impossible] doesn't consider their product cellular agriculture, it's part of a spectrum of innovation," Krueger says. "There are novel proteins that you're not going to find in your average food, and there's some cool tech there. So to me, that does show a lot of willingness on people's part to think about trying something new."

The message for those working on animal-based lab-grown meat is clear: People will accept innovation on their favorite food if it tastes good enough and evokes the same emotional connection as the real deal.

"How people talk about lab-grown meat now, it's still a conversation about science, not about culture and emotion," Lee says. But he's confident that the conversation will start to shift in that direction if the companies doing this work can nail the flavor memory, above all.

And then proving how much power flavor lords over us, we quickly derail into a conversation about Doritos, which he calls "maniacally delicious." The chips carry no health value whatsoever and are a native product of food engineering and manufacturing — just watch how hard it is for Bon Appetit associate food editor Claire Saffitz to try and recreate them in the magazine's test kitchen — yet devotees remain unfazed and crunch on.

"It's funny because it shows you that people don't ask questions about how [some foods] are made, so why are they asking so many questions about how lab-grown meat is made?" Lee asks.

For all the hype around Impossible Burger, there are still controversies and hand-wringing around lab-grown meat. Some people are grossed out by the idea, some people are confused, and if you're the U.S. Cattlemen's Association (USCA), you're territorial. Last year, the group sent a petition to the USDA to "exclude products not derived directly from animals raised and slaughtered from the definition of 'beef' and meat.'"

"I think we are probably three or four big food safety scares away from everyone, especially younger generations, embracing lab-grown meat as like, 'Science is good; nature is dirty, and can kill you.'"

"I have this working hypothesis that if you look at the nation in 50-year spurts, we revolve back and forth between artisanal, all-natural food that's unadulterated and pure, and food that's empowered by science," Lee says. "Maybe we've only had one lap around the track on that, but I think we are probably three or four big food safety scares away from everyone, especially younger generations, embracing lab-grown meat as like, 'Science is good; nature is dirty, and can kill you.'"

Food culture goes beyond just the ingredients we know and love — it's also about how we interact with them, produce them, and expect them to taste and feel when we bite down. We accept a margin of difference among a fast food burger, a backyard burger from the grill, and a gourmet burger. Maybe someday we'll accept the difference between a burger created by killing a cow and a burger created by biopsying one.

Looking to the Future

Every time we engage with food, "we are enacting a ritual that binds us to the place we live and to those in our family, both living and dead," Wilson writes in Consider the Fork. "Such things are not easily shrugged off. Every time a new cooking technology has been introduced, however useful … it has been greeted in some quarters with hostility and protestations that the old ways were better and safer."

This is why it might be hard for a vegetarian mother to try her daughter's lab-grown shrimp, no matter how ethically it was produced or how awe-inspiring the invention is. Yet food cultures can and do change. "They're not these static things," says Benjamin Wurgaft, a historian whose book Meat Planet: Artificial Flesh and the Future of Food comes out this month. "The real tension seems to be between slow change and fast change."

In fact, the very definition of the word "meat" has never exclusively meant what the USCA wants it to mean. Before the 12th century, when it first appeared in Old English as "mete," it wasn't very specific at all and could be used to describe anything from "nourishment," to "food item," to "fodder," to "sustenance." By the 13th century it had been narrowed down to mean "flesh of warm-blooded animals killed and used as food." And yet the British mincemeat pie lives on as a sweet Christmas treat full of -- to the surprise of many non-Brits -- spiced, dried fruit. Since 1901, we've also used this word with ease as a general term for anything that's substantive -- as in, "the meat of the matter." There is room for yet more definitions to pile on.

"The conversation [about lab-ground meat] has changed remarkably in the last six years," Wurgaft says. "It has become a conversation about whether or not specific companies will bring a product to market, and that's a really different conversation than asking, 'Should we produce meat in the lab?'"

As part of the field research for his book, Wurgaft visited the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, a Dutch museum that specializes in the history of science and medicine. It was 2015, and he was there to see an exhibit on the future of food. Just two years earlier, Mark Post had made that first lab-grown hamburger about a two-and-a-half hour drive south of the museum. When Wurgaft arrived, he found the novel invention, which Post had donated to the museum, already preserved and served up on a dinner plate, the whole outfit protected by plexiglass.

"They put this in the exhibit as if it were already part of the historical records, which to a historian looked really weird," Wurgaft says. "It looked like somebody taking the most recent supercomputer and putting it in a museum exhibit saying, 'This is the supercomputer that changed everything,' as if you were already 100 years in the future, looking back."

It seemed to symbolize an effort to codify a lab-grown hamburger as a matter of Dutch pride, perhaps someday occupying a place in people's hearts right next to the stroopwafel.

"Who's to say that we couldn't get a whole school of how to cook with lab-grown meat?"

Lee likes to imagine that part of the legacy of lab-grown meat, if it succeeds, will be to inspire entirely new fads in cooking -- a step beyond ones like the crab-filled avocado of the 1960s or the pesto of the 1980s in the U.S.

"[Lab-grown meat] is inherently going to be a different quality than anything we've done with an animal," he says. "Look at every cut [of meat] on the sphere today -- each requires a slightly different cooking method to optimize the flavor of that cut. Who's to say that we couldn't get a whole school of how to cook with lab-grown meat?"

At this point, most of us have no way of trying lab-grown meat. It remains exclusively available through sometimes gimmicky demos reserved for investors and the media. But Wurgaft says the stories we tell about this innovation, the articles we write, the films we make, and yes, even the museum exhibits we curate, all hold as much cultural significance as the product itself might someday.

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

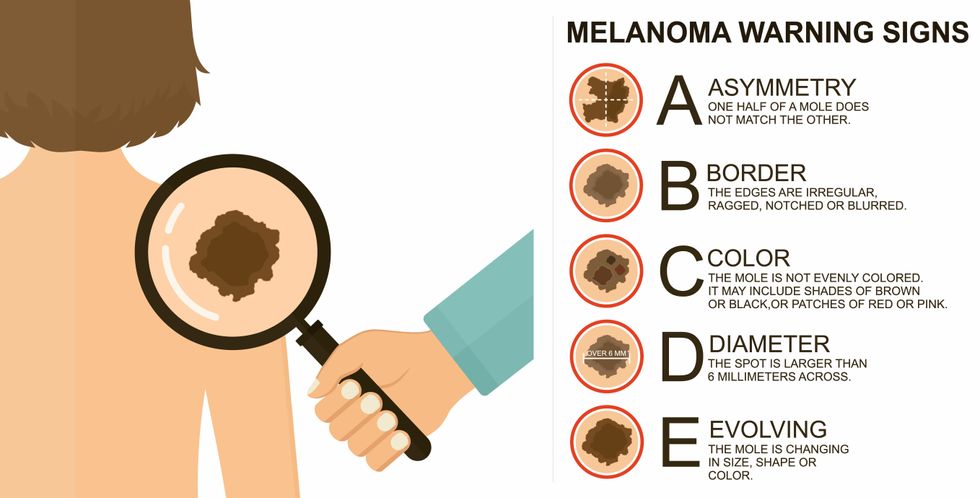

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.