Would You Want to Know a Decade Early If You Were Getting Alzheimer's?

The author pictured with her husband Dallas, who has Alzheimer's.

Editor's Note: A team of researchers in Italy recently used artificial intelligence and machine learning to diagnose Alzheimer's disease on a brain scan an entire decade before symptoms show up in the patient. While some people argue that early detection is critical, others believe the knowledge would do more harm than good. LeapsMag invited contributors with opposite opinions to share their perspectives.

I first realized something was wrong with my dad when I came home for Thanksgiving 20 years ago.

I hadn't seen my family for more than a year after moving from New York to California. My father was meticulous, a multi-shower a day man, a regular Beau Brummell. He was never officially diagnosed with dementia, but it was easy to figure out after he stopped leaving the house, stopped reading, stopped being himself. My mother knew, but she never sought help. After his illness showed itself, I asked her if she considered a nursing home. "Never," she told me. "I can take care of him." And she did.

She gave herself a break once to visit me, and it was the first time she traveled separately from him since they eloped at seventeen. My brother watched my father, and it was not smooth. Dad was angry, hallucinating, and demanding his gun, which had been disposed of long ago. While Mom was visiting me in California, we played some board games. One demanded honest answers. The card read, What are you most afraid of? "Dementia," she said.

My father never saw this coming, none of us did.

Dementia ran on my mother's side. Her mother, my Nana, was senile, the popular diagnosis for older folks back then. My grandfather tried his hardest to take care of her, but she kept escaping their tidy 6th floor apartment to run away. My mother would go over every day to take care of them, but once my grandfather became ill, she took her mother into our apartment. She had two small children, Nana, and her husband in a two-bedroom flat. Nana talked to people under plates, wore tissues on her head, and tried to escape. We were on the first floor, so she could run into traffic if all eyes weren't on her. Soon, it was too much, even for my Wonder Woman mom. Nana was placed in a nursing home and died soon after.

My mother dropped dead on a NYC sidewalk two years after my father started to deteriorate. She was probably going to the store to buy milk and cigarettes. A kind stranger called 911, and a cop came to my parent's door soon after to tell my dad the news. My father cried for death, raged and ranted, then calmed down enough to come back as the dad we remembered for the week of mourning. He even ordered a Manhattan at dinner. His death came exactly a week and an hour after my mother's. He died of a broken heart. My husband cried with all his body after we left the cemetery, weeping, "Poor Buck. Poor Buck." I never saw him cry before.

Now, 18 years later, I sit here with my husband, 59 years old, as he suffers from the same hideous disease.

He is talking to someone I can't see, even laughing with him. He holds a Ph.D. in literature, taught college, had a single handicap golf game, and ate well. We never saw this coming. One day he went to type and jumbled letters came on the screen. He would show up late or early for his classes, wondering what was wrong with the students. He started running red lights. He was graciously counseled to retire, and he did, at 55. His doctor told him it was depression. The second opinion agreed. He was told to do nothing for a year, and he did. He played golf a bit, then one day he couldn't speak or think clearly. I came home from work to find him roaming the neighborhood, eyes ablaze, muttering to himself. I went on family leave. Many tests later we got the working diagnosis, but it meant nothing to him. He never reacted to the words Primary Progressive Aphasia or dementia. I was glad. If he was lucid, I knew what he would talk about doing. He told me after my dad's death that he did not want that life for himself.

I worry I may get it, too. It almost seems inescapable. Dementia has no cure, and the treatments for the symptoms are hit and miss. I thought about getting the full flight of predictive tests, but I know myself, and I scare myself into bracing for the worst. Others scare me, too, when I read their online statements about ending their lives if they learn they have it: I told my children to take me to a state where assisted suicide is legal; it's easy to overdose; I don't want to be a burden on my children. These are caregivers on social media forums. They live with the terror, eyes wide open. We have no children, but who would I burden? My sisters? My brother? Do I stay or do I go? This disease invites pandemonium. Assisted murder-suicides with caregiver spouses of those with dementia don't merit headlines, but their stories are on the sidebars. No thanks. I work on God's timeline.

There are no survivors – yet.

A diagnosis today would paralyze me and create melancholy for all who know me. I would second guess everything, I would read everything, I would cry, I would hardly live. I would be tempted to pick up that first drink after 20 plus years sober. I would even think about ending my life. It would be difficult not to consider. As a high school English teacher, I talk about suicide when I teach Hamlet. I tell the students suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Dementia isn't temporary. There are no survivors – yet.

I often think what my relatives would have done with an advance diagnosis. My grandmother was a classic worrier. She would have been beyond distraught. My father might have found that gun. My husband would have taken the right number of pills.

An advance diagnosis would paralyze me.

I appreciate the arguments for early diagnosis. Some people are made of sterner stuff. They have the mindset I lack. I admire so many who are contributing to the current conversation about dementia and are active advocates for a cure. They have found a purpose in their fate.

I don't need a test to get my ducks in a row. Loving those with dementia has prompted me to be prepared. I have a different type of bucket list: reset my priorities, slow down, be present, educate others, and make my legal plans. If and when it happens, there will be time for toast and tea and a walk along the shore. There will be time to plan for the inevitable and unenviable end. I am morbid enough to know I will recognize the purple elephant in the room. I don't want the shock and awe now. I can wait. My sisters agree. We will keep our elbows out.

Editor's Note: Consider the other side of the argument here.

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

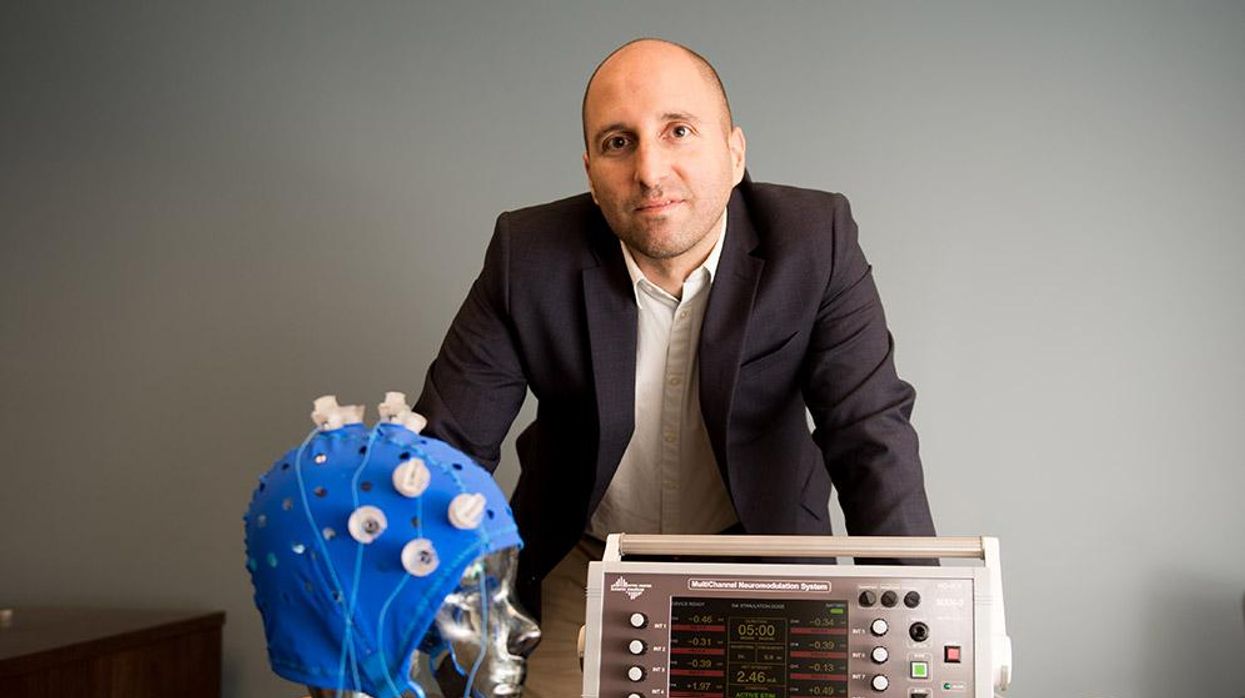

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”