Your Community and COVID-19: How to Make Sense of the Numbers Where You Live

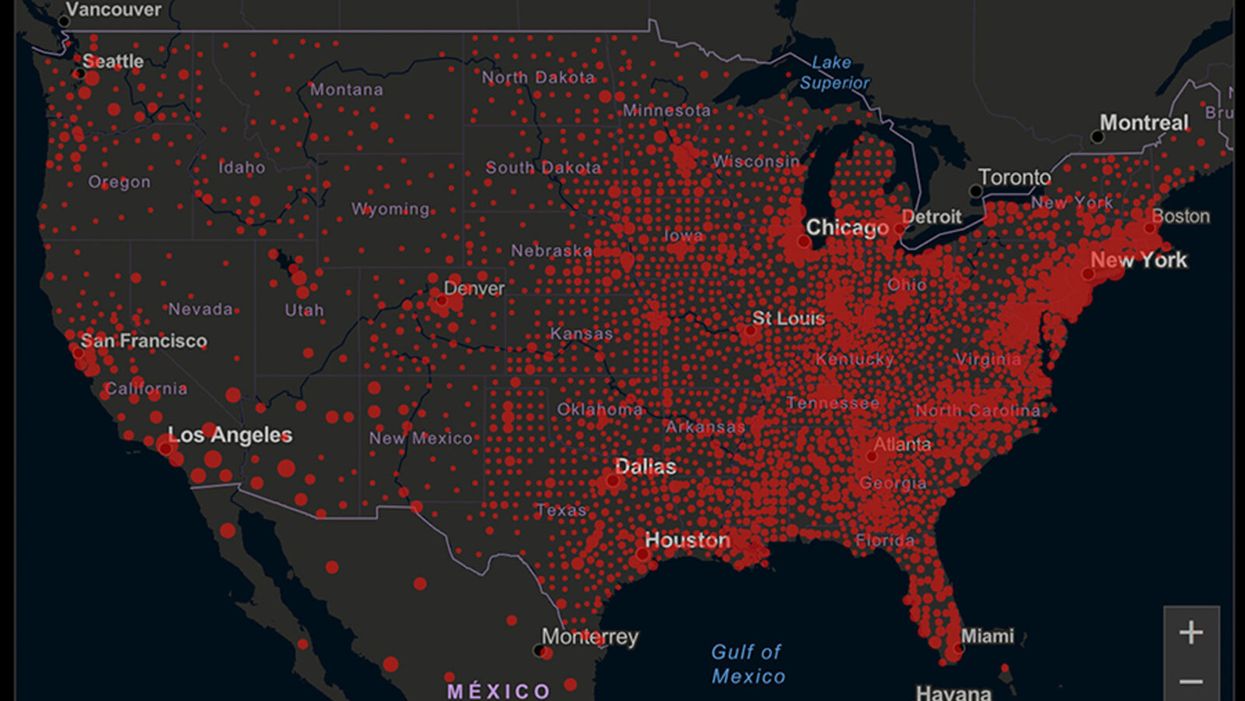

A map of cumulative known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., as of June 12th, 2020.

Have you felt a bit like an armchair epidemiologist lately? Maybe you've been poring over coronavirus statistics on your county health department's website or on the pages of your local newspaper.

If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

You're likely to find numbers and charts but little guidance about how to interpret them, let alone use them to make day-to-day decisions about pandemic safety precautions.

Enter the gurus. We asked several experts to provide guidance for laypeople about how to navigate the numbers. Here's a look at several common COVID-19 statistics along with tips about how to understand them.

Case Counts: Consider the Context

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in American counties is widely available. Local and state health departments should provide them online, or you can easily look them up at The New York Times' coronavirus database. However, you need to be cautious about interpreting them.

"Case counts are the obvious numbers to look at. But they're probably the hardest thing to sort out," said Dr. Jeff Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

That's because case counts by themselves aren't a good window into how the coronavirus is affecting your community since they rely on testing. And testing itself varies widely from day to day and community to community.

"The more testing that's done, the more infections you'll pick up," explained Dr. F. Perry Wilson, a physician at Yale University. The numbers can also be thrown off when tests are limited to certain groups of people.

"If the tests are being mostly given to people with a high probability of having been infected -- for example, they have had symptoms or work in a high-risk setting -- then we expect lots of the tests to be positive. But that doesn't tell us what proportion of the general public is likely to have been infected," said Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

These Stats Are More Meaningful

According to Dr. Wilson, it's more useful to keep two other statistics in mind: the number of COVID tests that are being performed in your community and the percentage that turn up positive, showing that people have the disease. (These numbers may or may not be available locally. Check the websites of your community's health department and local news media outlets.)

If the number of people being tested is going up, but the percentage of positive tests is going down, Dr. Wilson said, that's a good sign. But if both numbers are going up – the number of people tested and the percentage of positive results – then "that's a sign that there are more infections burning in the community."

It's especially worrisome if the percentage of positive cases is growing compared to previous days or weeks, he said. According to him, that's a warning of a "high-risk situation."

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at University of California at San Francisco, offered this tip: If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

There's one more caveat about case counts. It takes an average of a week for someone to be infected with COVID-19, develop symptoms, and get tested, Dr. Rutherford said. It can take an additional several days for those test results to be reported to the county health department. This means that case numbers don't represent infections happening right now, but instead are a picture of the state of the pandemic more than a week ago.

Hospitalizations: Focus on Current Statistics

You should be able to find numbers about how many people in your community are currently hospitalized – or have been hospitalized – with diagnoses of COVID-19. But experts say these numbers aren't especially revealing unless you're able to see the number of new hospitalizations over time and track whether they're rising or falling. This number often isn't publicly available, however.

If new hospitalizations are increasing, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

And there's an important caveat: "The problem with hospitalizations is that they do lag," UC San Francisco's Dr. Martin said, since it takes time for someone to become ill enough to need to be hospitalized. "They tell you how much virus was being transmitted in your community 2 or 2.5 weeks ago."

Also, he said, people should be cautious about comparing new hospitalization rates between communities unless they're adjusted to account for the number of more-vulnerable older people.

Still, if new hospitalizations are increasing, he said, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

Deaths: They're an Even More Delayed Headline

Cable news networks obsessively track the number of coronavirus deaths nationwide, and death counts for every county in the country are available online. Local health departments and media websites may provide charts tracking the growth in deaths over time in your community.

But while death rates offer insight into the disease's horrific toll, they're not useful as an instant snapshot of the pandemic in your community because severely ill patients are typically sick for weeks. Instead, think of them as a delayed headline.

"These numbers don't tell you what's happening today. They tell you how much virus was being transmitted 3-4 weeks ago," Dr. Martin said.

'Reproduction Value': It May Be Revealing

You're not likely to find an available "reproduction value" for your community, but it is available for your state and may be useful.

A reproduction value, also known as R0 or R-naught, "tells us how many people on average we expect will be infected from a single case if we don't take any measures to intervene and if no one has been infected before," said Boston University's Murray.

As The New York Times explained, "R0 is messier than it might look. It is built on hard science, forensic investigation, complex mathematical models — and often a good deal of guesswork. It can vary radically from place to place and day to day, pushed up or down by local conditions and human behavior."

It may be impossible to find the R0 for your community. However, a website created by data specialists is providing updated estimates of a related number -- effective reproduction number, or Rt – for each state. (The R0 refers to how infectious the disease is in general and if precautions aren't taken. The Rt measures its infectiousness at a specific time – the "t" in Rt.) The site is at rt.live.

"The main thing to look at is whether the number is bigger than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently growing in your area, or smaller than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently decreasing in your area," Murray said. "It's also important to remember that this number depends on the prevention measures your community is taking. If the Rt is estimated to be 0.9 in your area and you are currently under lockdown, then to keep it below 1 you may need to remain under lockdown. Relaxing the lockdown could mean that Rt increases above 1 again."

"Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing."

Keep in mind that you can still become infected even if an outbreak in your community appears to be slowing. Low risk doesn't mean no risk.

Putting It All Together: Why the Numbers Matter

So you've reviewed COVID-19 statistics in your community. Now what?

Dr. Wilson suggests using the data to remind yourself that the coronavirus pandemic "is still out there. You need to take it seriously and continue precautions," he said. "Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing. 'My state is doing well, no one I know is sick, is it time to have a dinner party?' No."

He also recommends that laypeople avoid tracking COVID-19 statistics every day. "Check in once a week or twice a month to see how things are going," he suggested. "Don't stress too much. Just let it remind you to put that mask on before you get out of your car [and are around others]."

Sharing land and other resources among farmers isn’t new. But research shows it may be increasingly relevant in a time of climatic upheaval.

The livestock trucks arrived all night. One after the other they backed up to the wood chute leading to a dusty corral and loosed their cargo — 580 head of cattle by the time the last truck pulled away at 3pm the next afternoon. Dan Probert, astride his horse, guided the cows to paddocks of pristine grassland stretching alongside the snow-peaked Wallowa Mountains. They’d spend the summer here grazing bunchgrass and clovers and biscuitroot. The scuffle of their hooves and nibbles of their teeth would mimic the elk, antelope and bison that are thought to have historically roamed this portion of northeastern Oregon’s Zumwalt Prairie, helping grasses grow and restoring health to the soil.

The cows weren’t Probert’s, although the fifth-generation rancher and one other member of the Carman Ranch Direct grass-fed beef collective also raise their own herds here for part of every year. But in spring, when the prairie is in bloom, Probert receives cattle from several other ranchers. As the grasses wither in October, the cows move on to graze fertile pastures throughout the Columbia Basin, which stretches across several Pacific Northwest states; some overwinter on a vegetable farm in central Washington, feeding on corn leaves and pea vines left behind after harvest.

Sharing land and other resources among farmers isn’t new. But research shows it may be increasingly relevant in a time of climatic upheaval, potentially influencing “farmers to adopt environmentally friendly practices and agricultural innovation,” according to a 2021 paper in the Journal of Economic Surveys. Farmers might share knowledge about reducing pesticide use, says Heather Frambach, a supply chain consultant who works with farmers in California and elsewhere. As a group they may better qualify for grants to monitor soil and water quality.

Most research around such practices applies to cooperatives, whose owner-members equally share governance and profits. But a collective like Carman Ranch’s — spearheaded by fourth-generation rancher Cory Carman, who purchases beef from eight other ranchers to sell under one “regeneratively” certified brand — shows when producers band together, they can achieve eco-benefits that would be elusive if they worked alone.

Vitamins and minerals in soil pass into plants through their roots, then into cattle as they graze, then back around as the cows walk around pooping.

Carman knows from experience. Taking over her family's land in 2003, she started selling grass-fed beef “because I really wanted to figure out how to not participate in the feedlot world, to have a healthier product. I didn't know how we were going to survive,” she says. Part of her land sits on a degraded portion of Zumwalt Prairie replete with invasive grasses; working to restore it, she thought, “What good does it do to kill myself trying to make this ranch more functional? If you want to make a difference, change has to be more than single entrepreneurs on single pieces of land. It has to happen at a community level.” The seeds of her collective were sown.

Raising 100 percent grass-fed beef requires land that’s got something for cows to graze in every season — which most collective members can’t access individually. So, they move cattle around their various parcels. It’s practical, but it also restores nutrient flows “to the way they used to move, from lowlands and canyons during the winter to higher-up places as the weather gets hot,” Carman says. Meaning, vitamins and minerals in soil pass into plants through their roots, then into cattle as they graze, then back around as the cows walk around pooping.

Cory Carman sells grass-fed beef, which requires land that’s got something for cows to graze in every season.

Courtesy Cory Carman

Each collective member has individual ecological goals: Carman brought in pigs to root out invasive grasses and help natives flourish. Probert also heads a more conventional grain-finished beef collective with 100 members, and their combined 6.5 million ranchland acres were eligible for a grant supporting climate-friendly practices, which compels them to improve soil and water health and biodiversity and make their product “as environmentally friendly as possible,” Probert says. The Washington veg farmer reduced tilling and pesticide use thanks to the ecoservices of visiting cows. Similarly, a conventional hay farmer near Carman has reduced his reliance on fertilizer by letting cattle graze the cover crops he plants on 80 acres.

Additionally, the collective must meet the regenerative standards promised on their label — another way in which they work together to achieve ecological goals. Says David LeZaks, formerly a senior fellow at finance-focused ecology nonprofit Croatan Institute, it’s hard for individual farmers to access monetary assistance. “But it's easier to get financing flowing when you increase the scale with cooperatives or collectives,” he says. “This supports producers in ways that can lead to better outcomes on the landscape.”

New, smaller scale farmers might gain the most from collective and cooperative models.

For example, it can help them minimize waste by using more of an animal, something our frugal ancestors excelled at. Small-scale beef producers normally throw out hides; Thousand Hills’ 50 regenerative beef producers together have enough to sell to Timberland to make carbon-neutral leather. In another example, working collectively resulted in the support of more diverse farms: Meadowlark Community Mill in Wisconsin went from working with one wheat grower, to sourcing from several organic wheat growers marketing flour under one premium brand.

Another example shows how these collaborations can foster greater equity, among other benefits: The Federation of Southern Cooperatives has a mission to support Black farmers as they build community health. It owns several hundred forest acres in Alabama, where it teaches members to steward their own forest land and use it to grow food — one member coop raises goats to graze forest debris and produce milk. Adding the combined acres of member forest land to the Federation’s, the group qualified for a federal conservation grant that will keep this resource available for food production, and community environmental and mental health benefits. “That's the value-add of the collective land-owner structure,” says Dãnia Davy, director of land retention and advocacy.

New, smaller scale farmers might gain the most from collective and cooperative models, says Jordan Treakle, national program coordinator of the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC). Many of them enter farming specifically to raise healthy food in healthy ways — with organic production, or livestock for soil fertility. With land, equipment and labor prohibitively expensive, farming collectively allows shared costs and risk that buy farmers the time necessary to “build soil fertility and become competitive” in the marketplace, Treakle says. Just keeping them in business is an eco-win; when small farms fail, they tend to get sold for development or absorbed into less-diversified operations, so the effects of their success can “reverberate through the entire local economy.”

Frambach, the supply chain consultant, has been experimenting with what she calls “collaborative crop planning,” where she helps farmers strategize what they’ll plant as a group. “A lot of them grow based on what they hear their neighbor is going to do, and that causes really poor outcomes,” she says. “Nobody replanted cauliflower after the [atmospheric rivers in California] this year and now there's a huge shortage of cauliflower.” A group plan can avoid the under-planting that causes farmers to lose out on revenue.

It helps avoid overplanted crops, too, which small farmers might have to plow under or compost. Larger farmers, conversely, can sell surplus produce into the upcycling market — to Matriark Foods, for example, which turns it into value-add products like pasta sauce for companies like Sysco that supply institutional kitchens at colleges and hospitals. Frambach and Anna Hammond, Matriark’s CEO, want to collectivize smaller farmers so that they can sell to the likes of Matriark and “not lose an incredible amount of income,” Hammond says.

Ultimately, farming is fraught with challenges and even collectivizing doesn’t guarantee that farms will stay in business. But with agriculture accounting for almost 30 percent of greenhouse gas emissions globally, there's an “urgent” need to shift farming practices to more environmentally sustainable models, as well as a “demand in the marketplace for it,” says NFFC’s Treakle. “The growth of cooperative and collective farming can be a huge, huge boon for the ecological integrity of the system.”

Story by Big Think

We live in strange times, when the technology we depend on the most is also that which we fear the most. We celebrate cutting-edge achievements even as we recoil in fear at how they could be used to hurt us. From genetic engineering and AI to nuclear technology and nanobots, the list of awe-inspiring, fast-developing technologies is long.

However, this fear of the machine is not as new as it may seem. Technology has a longstanding alliance with power and the state. The dark side of human history can be told as a series of wars whose victors are often those with the most advanced technology. (There are exceptions, of course.) Science, and its technological offspring, follows the money.

This fear of the machine seems to be misplaced. The machine has no intent: only its maker does. The fear of the machine is, in essence, the fear we have of each other — of what we are capable of doing to one another.

How AI changes things

Sure, you would reply, but AI changes everything. With artificial intelligence, the machine itself will develop some sort of autonomy, however ill-defined. It will have a will of its own. And this will, if it reflects anything that seems human, will not be benevolent. With AI, the claim goes, the machine will somehow know what it must do to get rid of us. It will threaten us as a species.

Well, this fear is also not new. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818 to warn us of what science could do if it served the wrong calling. In the case of her novel, Dr. Frankenstein’s call was to win the battle against death — to reverse the course of nature. Granted, any cure of an illness interferes with the normal workings of nature, yet we are justly proud of having developed cures for our ailments, prolonging life and increasing its quality. Science can achieve nothing more noble. What messes things up is when the pursuit of good is confused with that of power. In this distorted scale, the more powerful the better. The ultimate goal is to be as powerful as gods — masters of time, of life and death.

Should countries create a World Mind Organization that controls the technologies that develop AI?

Back to AI, there is no doubt the technology will help us tremendously. We will have better medical diagnostics, better traffic control, better bridge designs, and better pedagogical animations to teach in the classroom and virtually. But we will also have better winnings in the stock market, better war strategies, and better soldiers and remote ways of killing. This grants real power to those who control the best technologies. It increases the take of the winners of wars — those fought with weapons, and those fought with money.

A story as old as civilization

The question is how to move forward. This is where things get interesting and complicated. We hear over and over again that there is an urgent need for safeguards, for controls and legislation to deal with the AI revolution. Great. But if these machines are essentially functioning in a semi-black box of self-teaching neural nets, how exactly are we going to make safeguards that are sure to remain effective? How are we to ensure that the AI, with its unlimited ability to gather data, will not come up with new ways to bypass our safeguards, the same way that people break into safes?

The second question is that of global control. As I wrote before, overseeing new technology is complex. Should countries create a World Mind Organization that controls the technologies that develop AI? If so, how do we organize this planet-wide governing board? Who should be a part of its governing structure? What mechanisms will ensure that governments and private companies do not secretly break the rules, especially when to do so would put the most advanced weapons in the hands of the rule breakers? They will need those, after all, if other actors break the rules as well.

As before, the countries with the best scientists and engineers will have a great advantage. A new international détente will emerge in the molds of the nuclear détente of the Cold War. Again, we will fear destructive technology falling into the wrong hands. This can happen easily. AI machines will not need to be built at an industrial scale, as nuclear capabilities were, and AI-based terrorism will be a force to reckon with.

So here we are, afraid of our own technology all over again.

What is missing from this picture? It continues to illustrate the same destructive pattern of greed and power that has defined so much of our civilization. The failure it shows is moral, and only we can change it. We define civilization by the accumulation of wealth, and this worldview is killing us. The project of civilization we invented has become self-cannibalizing. As long as we do not see this, and we keep on following the same route we have trodden for the past 10,000 years, it will be very hard to legislate the technology to come and to ensure such legislation is followed. Unless, of course, AI helps us become better humans, perhaps by teaching us how stupid we have been for so long. This sounds far-fetched, given who this AI will be serving. But one can always hope.