Youth Climate Activists Expand Their Focus and Collaborate to Get Out the Vote

Young climate activists from left: Saad Amer, Isha Clarke, and Benji Backer.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

For youth climate activists, Earth Day 2020 was going to be epic. Fueled by the global climate strikes that drew millions of young people into streets around the world in 2019, the holiday's historic 50th anniversary held the promise of unprecedented participation and enthusiasm.

Then the pandemic hit. When the ability to hold large gatherings came to a screeching halt in March, just a handful of weeks before Earth Day, events and marches were cancelled. Activists rallied as best they could and managed to pull off an impressive three-day livestream event online, but like everything we've experienced since COVID-19 arrived, it wasn't the same.

Add on climate-focused candidate Bernie Sanders dropping out of the U.S. presidential race in April, and the spring of 2020 was a tough time for youth climate activists. "We just really felt like there was this energy sucked out of the movement," says Katie Eder, 19-year-old founder and Executive Director of Future Coalition. "And there was a lot of cynicism around the election."

Isha Clarke, 17-year-old cofounder of Oakland's Youth vs. Apocalypse, says she was "upset" and "depressed" the following month in the wake of George Floyd's murder. "It was like, I'm already here, stuck inside because of COVID," she recalls, "which is already disproportionately killing Black people and Indigenous people. And it's putting people out of work and making frontline communities even more vulnerable. And I'm missing my senior year, and everything is just crazy—and then this."

Isha Clarke

Clarke started doing some organizing around Black Lives Matter, which led her to consider the weight of this moment. "I was thinking about strategy and tactics, and I was thinking 'What is going to make this a pivotal moment in history, rather than just a memorable one?' And I think what is going to make this a pivotal moment is this real understanding and organizing around true intersectionality, on really finding the points on which our struggles intersect, and tear down this foundational system that is the root cause of all of these things."

Eder also says that the Black Lives Matter movement helped re-energize and re-focus the youth climate movement. "It sort returned this energy to young people that said, 'Okay, we don't need a presidential candidate to be the person driving this revolution. This is a people's revolution, and so that's what we need to do. So over the course of the summer we saw the climate movement showing up for the Black Lives movement in a big way, with that really being the priority."

Intersectionality—the idea that things like climate justice and racial justice and economic justice are not separate spheres, but rather interconnected issues that need to be tackled together—has become a dominating theme of the youth climate movement. In Clarke's opinion, white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism have led us to the climate crisis, and progress on the climate front must include addressing those issues.

"We know that to fix the problem we're going to need as many young people in the streets, voting, and in legislative offices as possible, and so far we've been able to work with pretty much anyone and everyone when there's overlap."

"Climate justice has to be about working to dismantle these systems of oppression in every way that they exist, whether that be through environmental racism or police brutality or our faulty education system or detention centers, or whatever that is," says Clarke. "There are so many ways in which these foundational systems of oppression are harming people."

Eder concurs. "I think we've known this all along, but it's heightened this year, that when we talk about climate justice, we have to talk about racial justice and social justice. That needs to be the leading theme. It's not just about the polar bears and the ice caps—it's about people. That's a people's problem, and that's what we need to keep coming back to, finding the humanity in the crisis that otherwise feels really abstract."

Now, with the election just weeks away, activists are focusing much of their energies on getting out the vote.

Saad Amer

Photo credit: Cassell Ferere

Saad Amer is the 26-year-old founder of Plus1Vote, an organization launched prior to the 2018 midterm elections that encourages voter registration and participation by asking everyone to bring one person with them to the polls. Amer, who holds a degree in Environmental Science and Public Policy from Harvard, has been an environmental activist since he was 13 and has traveled the world exploring different ways people and communities are trying to battle climate change.

"What I found was that there were just consistent barriers to actually accomplishing anything with regard to climate action," says Amer. "And what so much of it comes down to is our elected officials." He founded Plus1Vote to mobilize young adults to get out and vote with the logic that "young people could fundamentally swing the election in a direction of climate champions."

Plus1Vote doesn't just advocate for climate policy, though. It also folds the issues of gun violence, health care, voting rights, and social justice in its campaigns. Like the other activists we spoke to, intersectionality is key to Amer's approach to change—and voting in supportive elected officials is key to facilitating all of it.

"Whether you're a racial justice organization, whether you're a climate-focused organization, women's rights, whatever it is, there's a clear common denominator in how we can take action on every single one of those fronts," says Amer. That common denominator is voting.

Saad Amer leads climate justice/racial justice march in the summer of 2019.

One quirk of youth activism is that many of the young people in the trenches aren't even old enough to vote themselves. Isha Clarke still has another year before she reaches voting age, but that isn't stopping her from pushing to get out the vote. In fact, her latest collaborative project is a campaign called "This is the Time," which launches in October and includes an action website where voting-age Americans can pledge to fight for the future and to vote for candidates who will too.

However, it would be a mistake to assume that all young climate change activists share the same political views—or even sit on the same side of the political aisle.

Benji Backer is a 22-year-old from Appleton, Wisconsin, who has been active in conservative politics since he was 10. Growing up in a family where "the environment was the number one value," Backer found himself frustrated with the political divide when it comes to the environment. So he decided to change it.

In 2017, he founded the American Conservative Coalition to make environmentalism bipartisan again, and to put forth market-based, limited-government ways to solve environmental challenges.

Backer says we need both sides at the table to solve the problem of climate change. He testified before Congress next to Greta Thunberg, and though they don't agree on everything, they shared the unified message that their generation was being left behind because of the unnecessary politicizing of climate change.

"Our generation doesn't look at the environment from a conservative vs. liberal angle," says Backer. "They look at it from an environmental angle. And to most young people, there's a deep frustration at the lack of action on a lot of issues, but most importantly climate change, because everyone knows it's a problem."

Backer believes that local, state, and federal governments have a role to play in solving climate change, but that role should be more about incentivising innovation in the marketplace than implementing hefty regulations. "The marketplace has spurred innovation and competition to create electric vehicles, to create better solar panels, to create wind energy," says Backer. "That's the marketplace doing it's thing." He points out that we don't have all the answers to solving climate change yet, and that we need to encourage innovation and technology in the marketplace to help us get there faster.

To show how companies are already playing a role in finding climate change solutions, Backer is currently on a 50-day tour of the country—in a Tesla—dubbed the "Electric Election Road Trip." His team is interviewing 40 companies, sharing their sustainability initiatives in a podcast, and compiling the experience into a documentary that will be released sometime next year.

Benji Backer gets a tour of Michigan University's Nuclear Lab

Credit: Keegan Rice.

Despite their different approaches to solutions, climate change activists across the political spectrum have found ways to work together. "We definitely collaborate on messaging," says Backer, "the importance of fighting climate change, the importance of youth action. And we know that to fix the problem we're going to need as many young people in the streets, voting, and in legislative offices as possible, and so far we've been able to work with pretty much anyone and everyone when there's overlap."

"And when there's not overlap," he adds, "we just go our separate ways for that specific issue."

There's no doubt that the pandemic and political upheaval we're all experiencing pose challenges to youth activists, but these young leaders are adjusting and charging ahead. The digital savvy they possess makes mobilizing and collaborating easier for them than for older generations, and they certainly aren't going to let a global virus outbreak stop them. The most striking thing about these young people is how their environmental knowledge, activism know-how, and ability to express themselves feels far beyond their years, without exception. While they're having to endure the uncertainty of the moment while navigating a pivotal stage of their own lives, these youth continue to provide a hopeful perspective and vision of the future—one that the world desperately needs.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

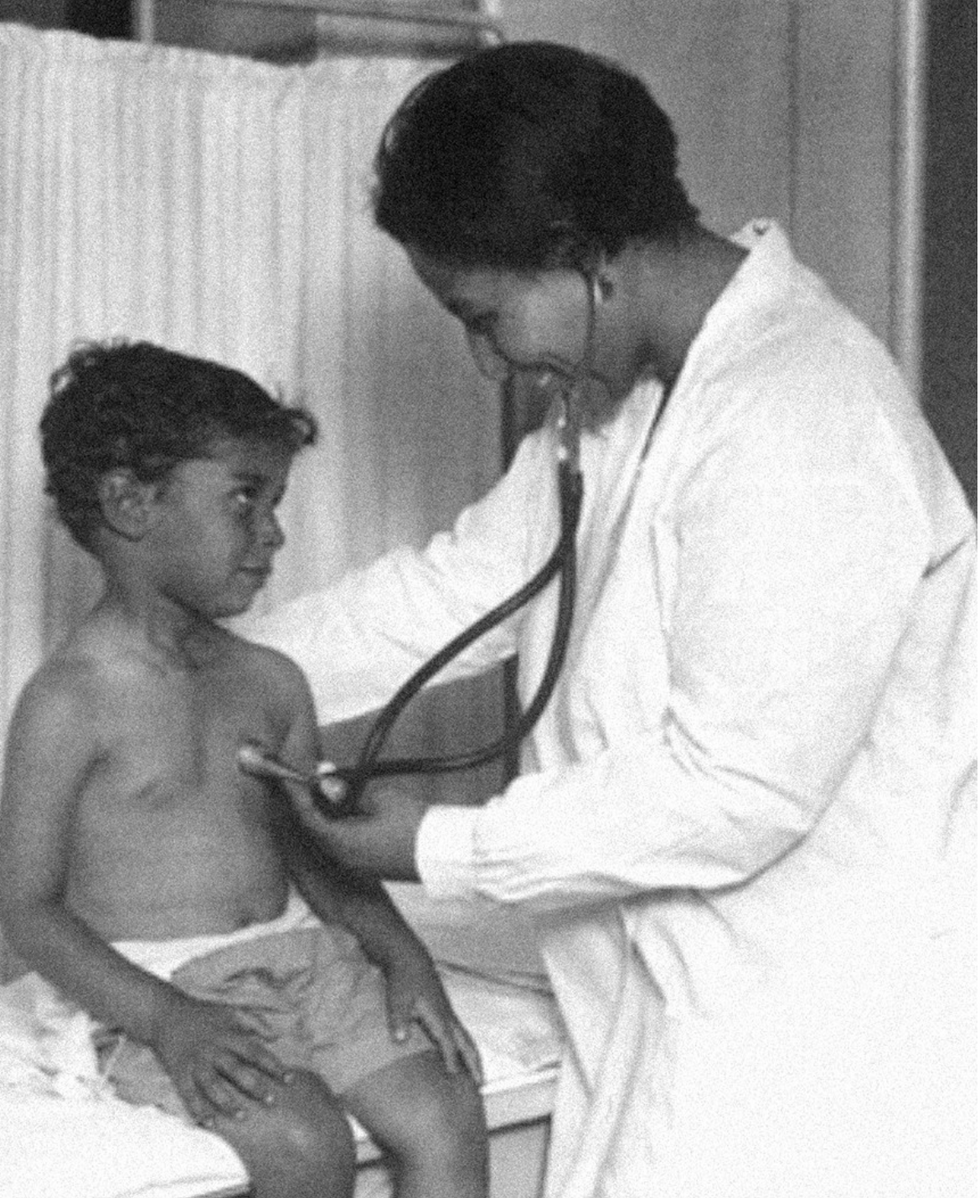

Dr. May Edward Chinn

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

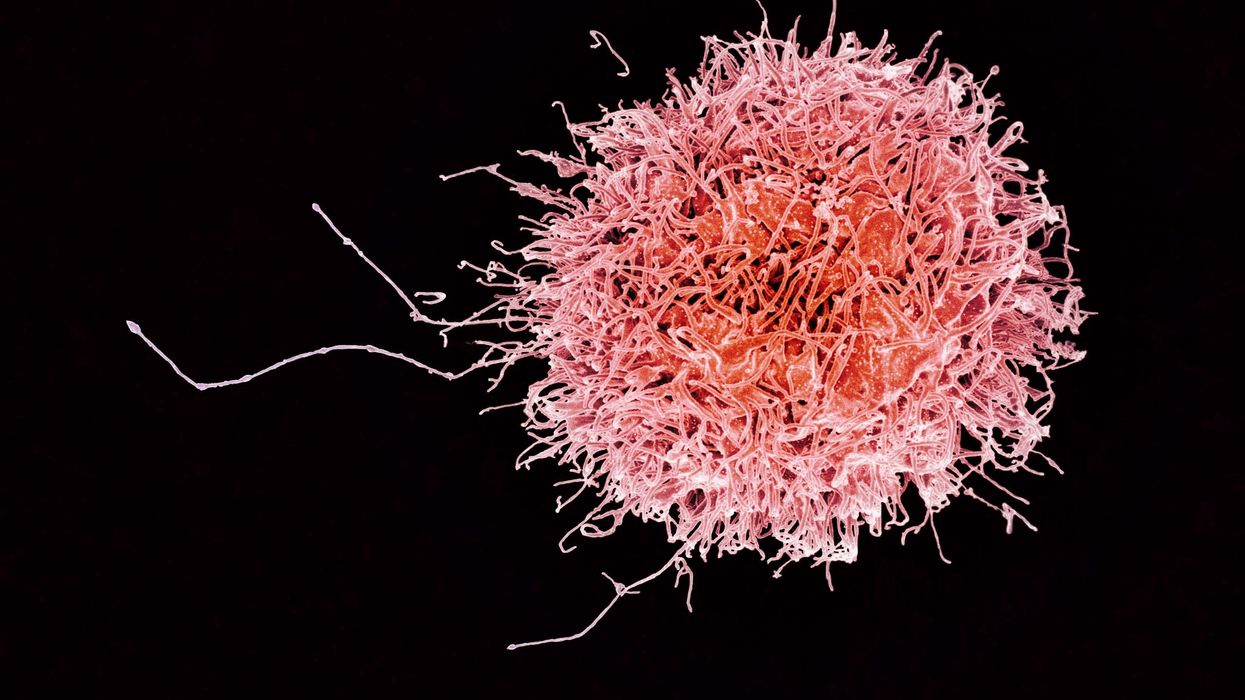

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business